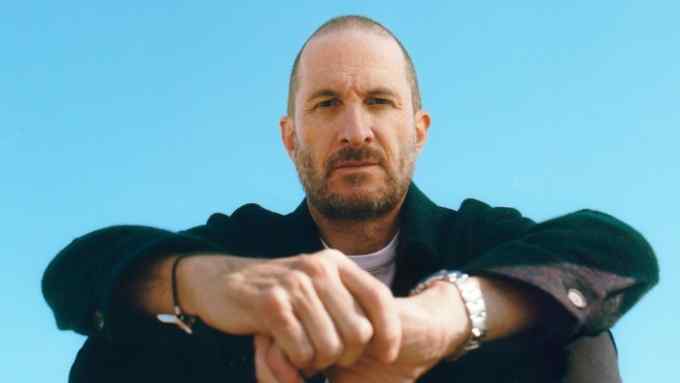

Jerzy Skolimowski on his Oscar contender EO: ‘Sometimes the donkey appears in my dreams’

Simply sign up to the Film myFT Digest -- delivered directly to your inbox.

Given that Jerzy Skolimowski has been making films over the past seven decades, you might expect his current work to be in that modestly contemplative mode that tends to be labelled “late-period”. But at 84, Skolimowski has made a film that is as audaciously inventive as anything he has done since the mid-1960s, when he first made his mark as an enfant terrible of Polish cinema.

The winner of the Jury Prize at last year’s Cannes Film Festival, and now shortlisted for an Oscar as Best International Feature, Skolimowski’s EO is not remotely a straightforward narrative, more a picaresque string of vignettes tracing the journeys of its protagonist — who happens to be a donkey.

On a Zoom call from Santa Monica, California, Skolimowski says that he and his wife Ewa Piaskowska — his co-writer and co-producer — were determined to avoid the well-beaten narrative path. “It’s boring, it’s almost office work if you try to follow all those rules.”

EO is cinema’s second visionary donkey film — the first being Robert Bresson’s Au Hasard Balthazar in 1966. Skolimowski has talked about how moved he was when he saw the film back then. But EO is a very different beast, and was sparked by an encounter in Sicily, where Skolimowski and Piaskowska spend their winters. It was at a village Nativity, in a barn full of animals: “You hear an incredible cacophony — chickens, geese, pigs, goats . . . In the very far corner, I saw those famous ears . . . ” Skolimowski lifts his hands and mimes donkey ears, “moving this way, that way. But the donkey kept silent, it was like a witness on the side. I came very close and I looked at his eyes — next time you see a donkey, please notice the enormous eyes. They had this very specific melancholic look — not being involved, but looking with a distance and maybe some philosophical reflection.”

The donkey — named “EO”, as in “hee-haw” — is an Everybeast, trotting through a sometimes dangerous world (often steeped in apocalyptic shades of blood red), repeatedly encountering human folly and fallibility. Skolimowski’s star is in fact six different animals, all of the same breed, Sardinians — “To me, the most beautiful breed.” EO, Skolimowski says, is very much informed by his and Piaskowska’s love of nature, which has deepened since they have been living in a forest in Poland’s Masuria region. “The nearest shop is a solid half-hour drive. But the advantage is that we live in real nature. There are wild animals which we see every day — suddenly a deer comes out of the bushes and stops in front of you. It changed our attitude towards animals. They’re no longer abstract creatures somewhere far away — we live among them.”

While EO doesn’t come across primarily as a film with a message — it’s too poetically elusive for that — Skolimowski hopes it will help change attitudes. “I’m ashamed by certain human activities, and the worst of it is industrial farming. Everyone should have some knowledge of the conditions those animals live in. If you can call it a life — it’s just macabre.”

As a young man, Skolimowski had little interest in film, but started out as a poet, with some amateur welterweight boxing on the side: “I had maybe 11 or 13 fights, nearly half of them I lost.” He got into cinema by accident, he says. At a writers’ workshop in Warsaw, he happened to be sitting at dinner next to Polish director Andrzej Wajda, who was working on a script about young people. “Because I was the only young person there, he decided to consult me. I read the first draft and I said, ‘This is all nonsense, young people don’t behave like this.’” As a result, Wajda enlisted him as co-writer on the film, 1960’s Innocent Sorcerers, also casting him as a boxer.

Skolimowski went on to co-write Roman Polanski’s first feature, Knife in the Water (1962), and now he and Pieskowska have collaborated on Polanski’s forthcoming film The Palace. I start to ask about Polanski, but Skolimowski delicately evades the topic — as you well might when you’re engaged in an Oscars campaign.

In 1965, Skolomowski directed and starred in his own first feature, Rysopis (Identification Marks: None), a jagged, nervy picture of youthful alienation. His career in Poland came to an end in 1967 when his satire Hands Up! was banned by the authorities. Leaving the country, he arrived in England at the height of Swinging London: “I was very excited. It was a bizarre world for me, people behaved completely differently. It was the era of flower children, and I become one of them.” (Indeed, one photo from the era shows him grinning under a velvet fedora, going full Austin Powers.)

One product of his time in London was Deep End (1970), a nightmarish black comedy set in a rundown swimming pool, where the sexual revolution painfully rubs up against entrenched English hang-ups. A similarly caustic worldview comes across in 1982’s Moonlighting, with Jeremy Irons, about Polish workmen stranded in a hostile, xenophobic London.

Today, Skolimowski has again fully become a Polish film-maker after a globetrotting career and several years living in the US. There have also been occasional acting roles in films by the likes of David Cronenberg and Julian Schnabel, and even in Marvel’s The Avengers, where his thick accent and pugilist’s profile got him cast as a Russian heavy. After a 17-year break from directing, Skolimowski resumed operations in 2008, re-establishing himself with inventive one-offs such as Essential Killing — a manhunt drama with Vincent Gallo — and the audaciously tricksy multi-strand 11 Minutes.

He has also pursued a parallel career as a non-figurative painter, with numerous solo shows on both sides of the Atlantic since the mid-1990s. A recent exhibition and catalogue of his work is titled In Painting I Can Do Anything — suggesting, presumably, that in film he can’t?

“In painting, I’m alone — no one is mixing my paints, it’s a one-on-one artistic fight. When you’re making a film it’s more like going to the factory, where you are just the head guy giving the orders, and it’s always a lot of noise, a lot of commotion and arguments. You have a huge group of collaborators and everybody brings something to the film.”

The benefits of that are something he has only realised belatedly, he says. “I always wanted to be the sole auteur. I was perhaps not totally fair towards my collaborators — because of course I was grabbing their ideas and adapting them to my, let’s call it, style.” That changed significantly with EO, he says: “For the very first time I was able to accept the input of my collaborators and really prized them for it.”

Since EO’s Cannes debut, Skolimowski says, he hasn’t had time to think about a next project — and then, films have a way of haunting you. “Sometimes the donkey appears in my dreams. I miss that animal very much.”

‘EO’ is in UK cinemas from February 3. A Skolimowski retrospective plays at BFI Southbank, London from March 27-April 30

Comments