Raise a glass! It's the 100th anniversary of Prohibition.

In January 1920, the 18th Amendment went into effect, outlawing the sale of alcoholic beverages in the United States and ushering in an age of rebellion.

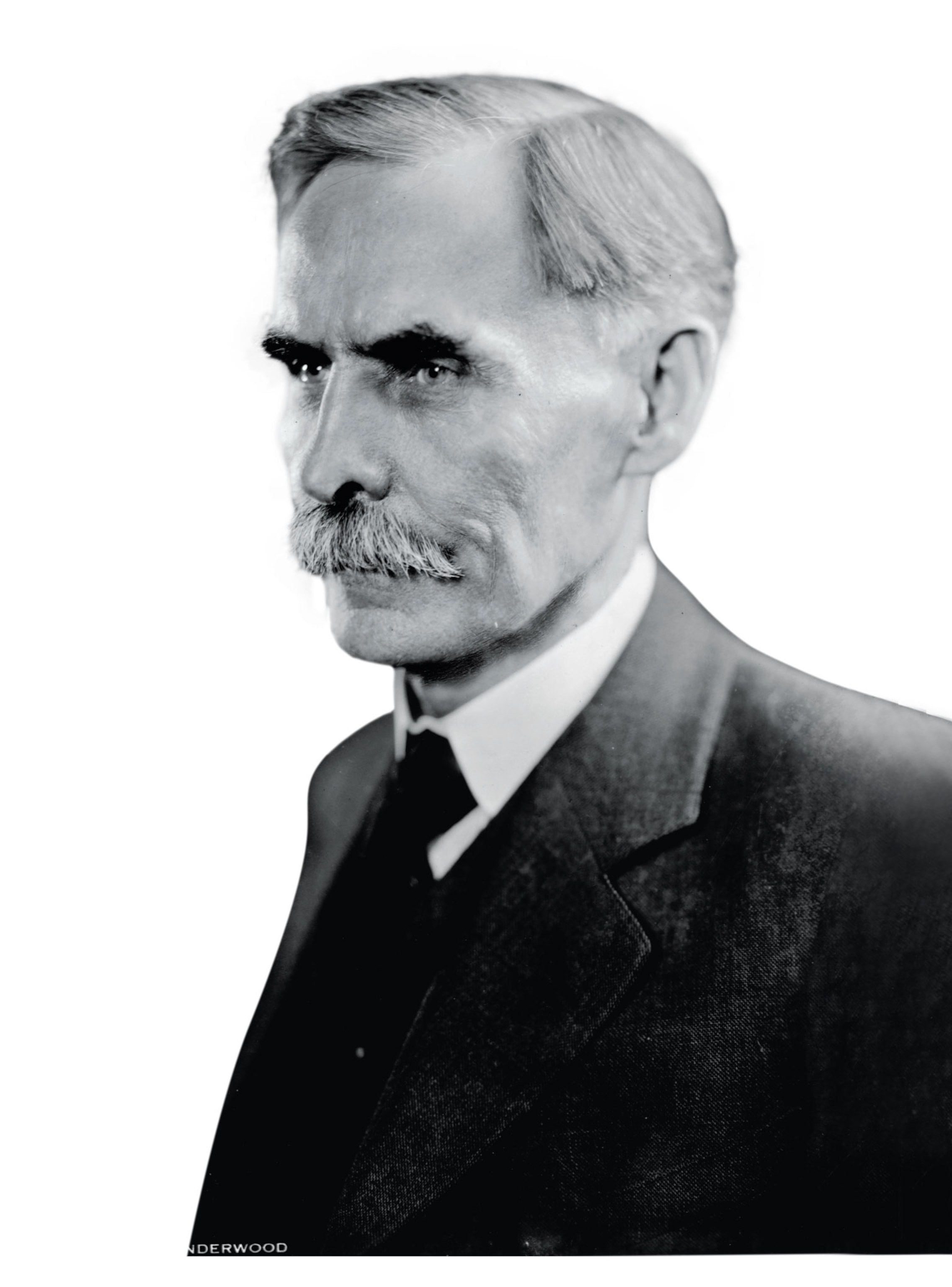

On January 17, 1920, brewing and selling alcoholic beverages became illegal in the United States as the 18th Amendment to the Constitution went into effect. This “noble experiment,” as described by its backers, was celebrated by temperance advocates across the country. Before a crowd of 10,000 people, popular evangelist Billy Sunday (a former baseball player) said: “Tonight, one minute after midnight, a new nation will be born … An era of clear ideas and good manners begins. The slums will soon be a thing of the past. Prisons and reformatories will be emptied; we will transform them into attics and factories. Again, all men will walk straight, all women will smile, all children will laugh. The gates of hell have closed forever.”

Prohibition would last for more than a decade, but the “new nation” promised by Sunday and others like him never arrived.

Temperance and teetotalers

The 18th Amendment was ratified in January 1919, and it banned the “manufacture, sale, or transportation of intoxicating liquors” as well as their importation and exportation through the then 48 states. Several months later, Congress passed the Volstead Act to cover other alcoholic beverages, including beer and wine. The Volstead Act also allowed for a few exceptions, such as medicinal usage and use in sacred rites. Possession and drinking were still legal since the law targeted those who supplied liquor, not those who consumed it.

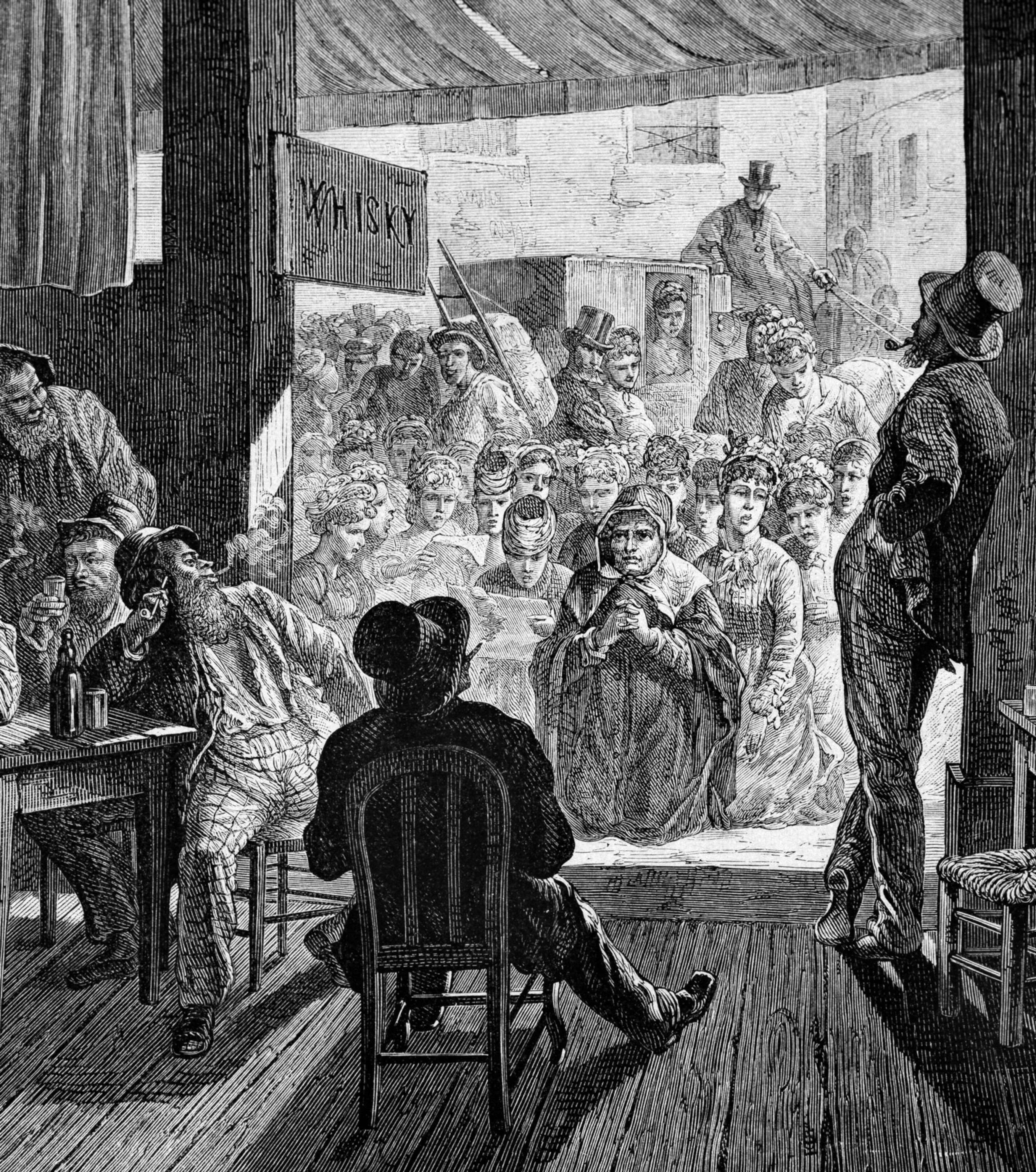

Prohibition’s history stretches back into the 19th century when religious groups and social organizations, such as the American Temperance Society, fought against the “scourge of alcohol” and drunkenness. In the 1850s Maine and other states experimented with laws banning alcohol, but local opposition brought about their eventual reversal.

(Meet the female sheriff who lead a Kentucky town through Prohibition.)

Women’s groups played a significant role. Activists argued that drink fueled violence in the home as drunken husbands would beat their wives and children. Temperance advocates argued that alcohol abuse caused poverty. In the 1870s the Woman’s Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) launched a major campaign to prohibit alcohol in support of the crusade mounted by the Prohibition Party, founded in 1869. Teetotalers, a 19th-century term for people who abstained from all alcohol, even made it to the White House. President Rutherford B. Hayes and his wife Lucy did not drink alcohol nor would they serve it.

In the 1890s this campaigning effort was boosted by a well-organized lobbying group, the Anti-Saloon League (ASL). Some employed prayers against the dens of alcoholic damnation, while others attacked them physically, such as the activist Carry Nation, who was notorious for using a hatchet to vandalize bars in the 1900s.

Prayers and Hatchets

Religion played a crucial role in the activities of female temperance activists. The Woman’s Christian Temperance Union was founded in 1874 to influence states to adopt anti-alcohol legislation. Singing and praying, activists visited saloons in the hope that piety would close their doors. Some activists went further: Carry Nation, a temperance activist who also supported women’s suffrage, used rocks and even an ax to break bottles and bust up bars: “You refused me the vote, and I had to use a rock,” she said.

Calls for a “dry” America continued into the 1910s. World War I brought gains for them when Congress approved a ban on alcohol for the duration of the war. They continued to pressure Congress for a prohibition amendment. Legislation was approved by both houses of Congress, and in January 1919, it was ratified after three-fourths of the states had passed it. It would go into effect in January 1920. Wayne Wheeler of the ASL worked with Representative Andrew Volstead to write the Volstead Act (formally known as the National Prohibition Act), which outlined how the new amendment would be applied and enforced.

(Read now: The highs and lows of hard apple cider history.)

Rumrunners and bootleggers

Criminals looked at the new law and saw an opportunity for profit. The United States was surrounded by nations that made spirits: Canada had whisky, and the Caribbean had rum. To sneak alcohol into the U.S. market, all a bootlegger needed was money, transportation, and muscle. Thousands of "thirsty" American customers would pay higher prices for booze, so potential profits were massive.

(Were humans hardwired to drink alcohol?)

Bootleggers operated in cities across the United States. In Detroit the Purple Gang controlled local distribution coming in from Canada. In New York Italian immigrants formed the Five Families and kept the city “wet.” Charles “Lucky” Luciano became New York’s top bootlegger by working with boss Arnold Rothstein and gangsters like Dutch Schultz.

In Chicago Al “Scarface” Capone and Johnny Torrio formed “The Outfit” to control liquor distribution in the city. Capone grew rich off of crime: Some sources put his estimated annual income as high as $60 million. As operations expanded and became more complex, gangsters began to organize. They hired more people: lawyers, brewers, boat captains, and truckers. They purchased defunct breweries and began cooking up their own “hooch” for sale.

A New Age for Women

The 1920s were an exciting time for American women who gained the right to vote when the 19th Amendment was passed shortly after Prohibition went into effect. In the cities, more young women were entering the workforce and enjoying the independence urban life afforded them, including enjoying a drink in mixed company at a local speakeasy. As it became clear that Prohibition was failing, many women became politically involved in repealing it. The Molly Pitcher Club, the Women’s Organization for National Prohibition Reform, and the Women’s Moderation Union all lobbied against the 18th Amendment until it was repealed in December 1933.

Crime families initially limited activity to their local area, but rivalries and conflict soon broke out as they sought to expand. Rivalries often resulted in violence: shootings, bombings, and murders. Capone’s taste for violence was notorious, and he consolidated control over bootlegging in Chicago by killing his enemies.

The most famous incident associated with him was the St. Valentine’s Day Massacre in February 1929. Seven men in the Irish mob were shot in a garage on Chicago’s North Side. Many believe Capone ordered the murders to eliminate his rival Bugs Moran.

Speakeasies and gin joints

Customers looking for alcohol would go to underground businesses called speakeasies or gin joints. In the city of New York alone, 15,000 saloons existed in 1920 prior to Prohibition. After the law’s passage, the number increased dramatically. Exact counts vary, but historians put the number anywhere between 32,000 and 100,000 establishments. Some were modest places that sold cheap booze, while others were stylish nightclubs that featured cocktails, jazz music, and dancing.

(During prohibition, nightlife thrived at these clubs.)

Fueled by bootleg alcohol, the 1920s became known as the Jazz Age, a term coined by F. Scott Fitzgerald, author of The Great Gatsby (1925). During this time, women were enjoying greater freedoms, in part because they achieved the right to vote in 1920. They shook off older social conventions and embraced speakeasy culture not only by drinking cocktails but also by defying social conventions. Nicknamed “flappers,” they bobbed their hair, wore shorter, loose-fitting dresses, smoked cigarettes, and danced.

In New York City three women— Texas Guinan, Helen Morgan and Belle Livingstone—ran some of the city’s swankiest nightclubs where men and women could mingle and drink in the nightlife during the 1920s to early ’30s. Celebrities such as Babe Ruth, Charles Lindbergh, Charlie Chaplin, Rudolph Valentino, and Clara Bow were often spotted at establishments like these.

A new amendment

Crime syndicates had grown and gained power by corrupting local authorities. Attempts to thwart bootleggers proved futile, and public opinion, especially in cities, turned against Prohibition. By 1927 it was plain to see that the “noble experiment” was a disaster. To end Prohibition would take nothing short of an amendment.

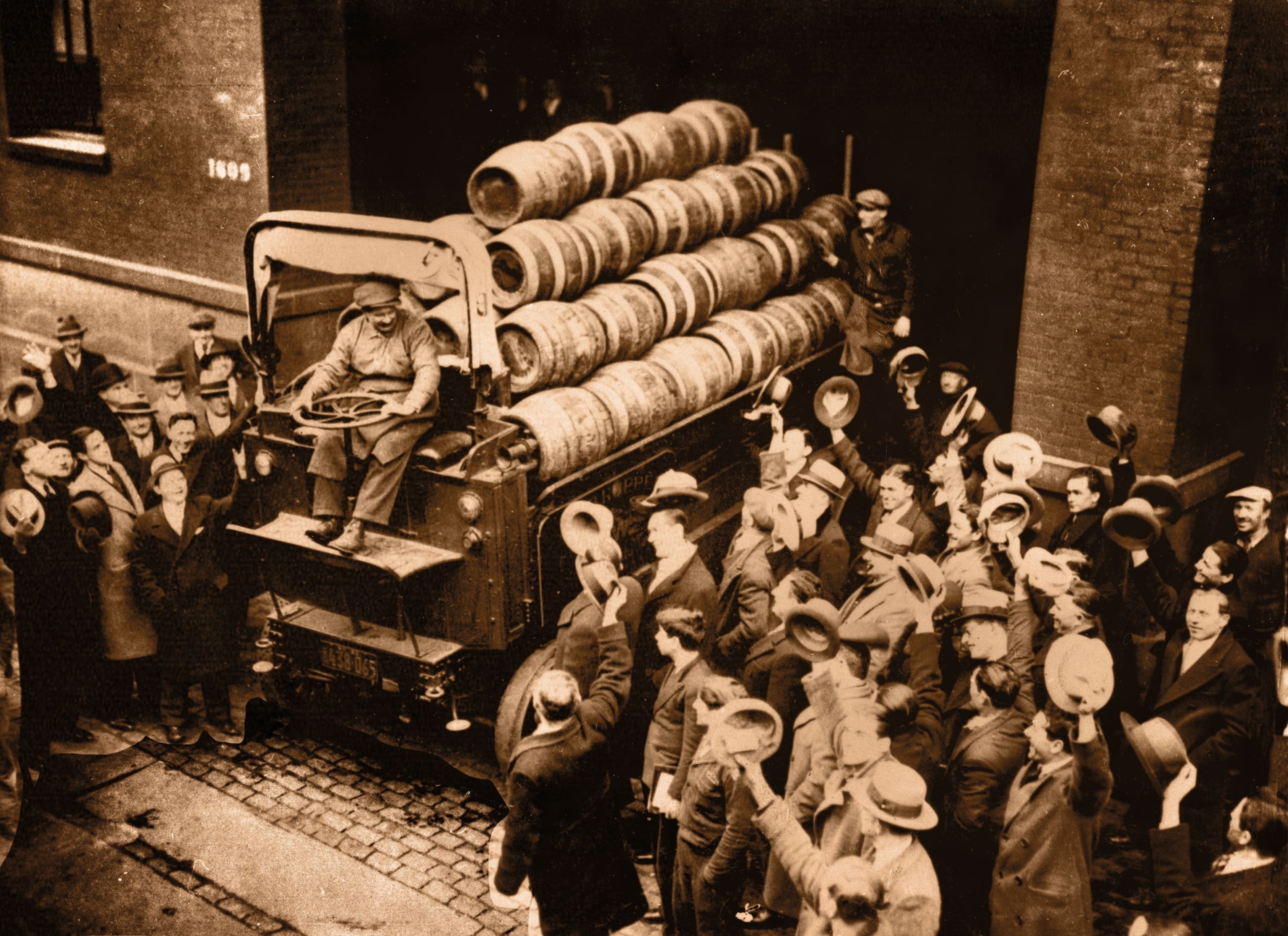

Change came after the 1932 presidential election when Franklin D. Roosevelt won a landslide victory against sitting president Herbert Hoover. In February 1933 both houses of Congress passed drafts of the 21st Amendment and sent it to the states for ratification. It was quickly ratified by December that same year. The 21st Amendment repealed the 18th, ending the noble experiment.

Ending Prohibition yielded good things for the government, which benefited from tax revenue on alcohol that helped combat the Great Depression plaguing the nation. Pop culture seemed to echo the sentiment as songs like “Happy Days Are Here Again” and “Cocktails for Two” rang out and bubbled to everyone’s lips.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Charlotte, the 'virgin birth' stingray, has a diseaseCharlotte, the 'virgin birth' stingray, has a disease

- See how billions of cicadas are taking over the U.S. this summerSee how billions of cicadas are taking over the U.S. this summer

- Why are orcas ramming boats? They might just be bored teenagersWhy are orcas ramming boats? They might just be bored teenagers

- These pelicans are starving to death—despite plenty to eatThese pelicans are starving to death—despite plenty to eat

- The world's largest fish are vanishing without a traceThe world's largest fish are vanishing without a trace

Environment

- 2024 hurricane season forecasted to be record-breaking year2024 hurricane season forecasted to be record-breaking year

- Connecting a new generation with South Africa’s iconic species

- Paid Content

Connecting a new generation with South Africa’s iconic species - These images will help you see coral reefs in a whole new wayThese images will help you see coral reefs in a whole new way

- What rising temps in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlifeWhat rising temps in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlife

- He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?

History & Culture

- Think customer service is bad now? Read this ancient complaintThink customer service is bad now? Read this ancient complaint

- The tragic backstory of one of the most haunted roads in AmericaThe tragic backstory of one of the most haunted roads in America

- The missing heiress at the center of New York’s oldest cold caseThe missing heiress at the center of New York’s oldest cold case

- When a people's stories are at risk, who steps in to save them?When a people's stories are at risk, who steps in to save them?

- I wrote this article with a 18th century quill. I recommend it.I wrote this article with a 18th century quill. I recommend it.

- Why this Bronze Age village became known as ‘Britain’s Pompeii’Why this Bronze Age village became known as ‘Britain’s Pompeii’

Science

- How being the oldest or youngest sibling shapes your personalityHow being the oldest or youngest sibling shapes your personality

- Tuberculosis is rising in the U.S. again. How did we get here?Tuberculosis is rising in the U.S. again. How did we get here?

- Are ultra-processed foods as addictive as cigarettes?Are ultra-processed foods as addictive as cigarettes?

- Epidurals may do more than relieve pain—they could save livesEpidurals may do more than relieve pain—they could save lives

Travel

- 7 things you need to know about European travel this summer7 things you need to know about European travel this summer

- These Algerian communities live in the Saharan sand seasThese Algerian communities live in the Saharan sand seas

- This German city doesn’t exist, according to a conspiracy theoryThis German city doesn’t exist, according to a conspiracy theory

- The best way to experience Slovenian cuisine? On two wheelsThe best way to experience Slovenian cuisine? On two wheels