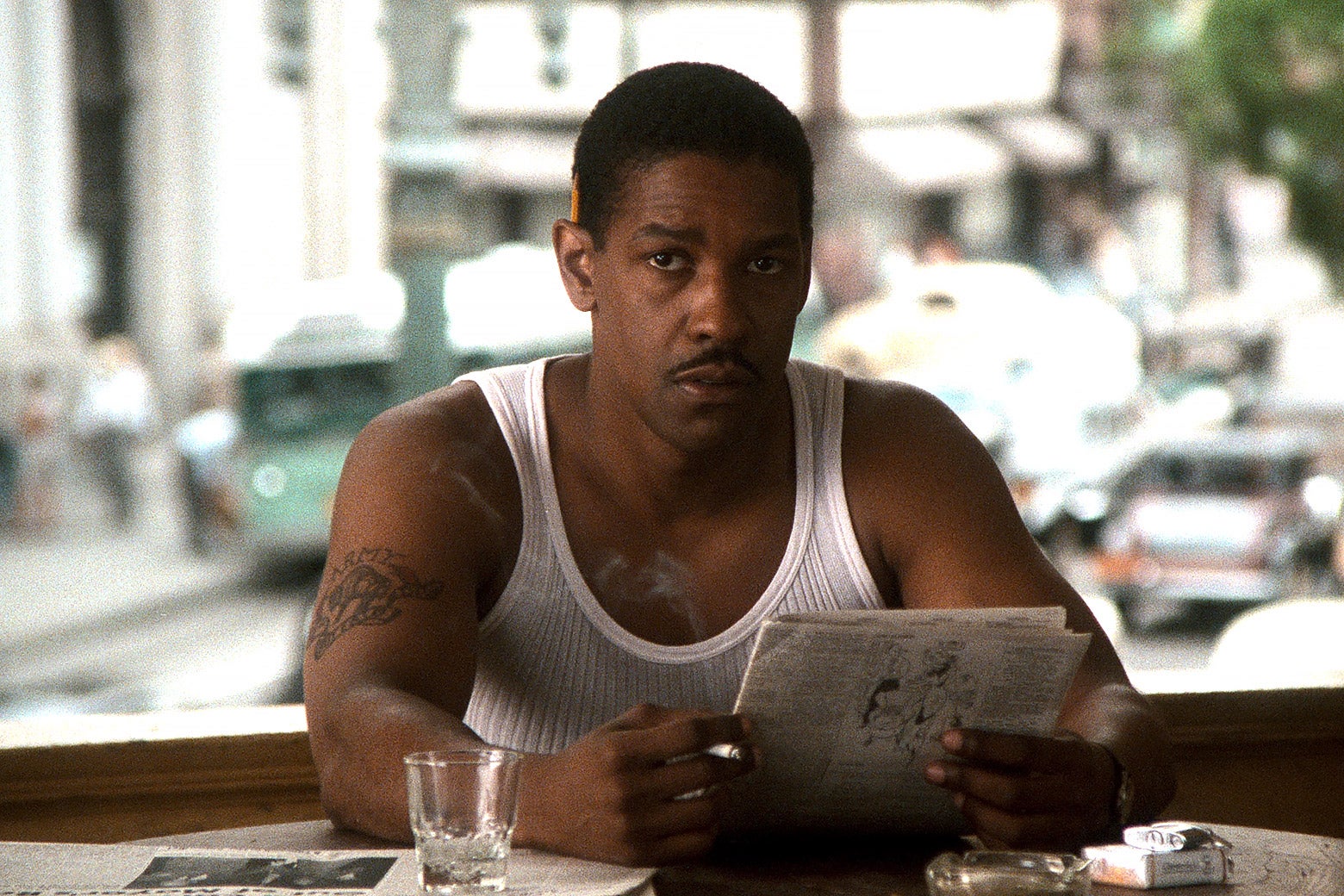

When Devil in a Blue Dress hit theaters in 1995, it should’ve been huge: a stylish thriller based on the first book in the bestselling Easy Rawlins mystery series, starring Denzel Washington at his most marketable, just after his early-’90s trifecta of Malcolm X, Philadelphia, and The Pelican Brief. But the movie disappointed at the box office, despite great reviews and a live-wire supporting performance by Don Cheadle as Easy’s homicidal friend Mouse. (Cheadle won awards from the LA Film Critics and the National Society of Film Critics for his breakout role.)

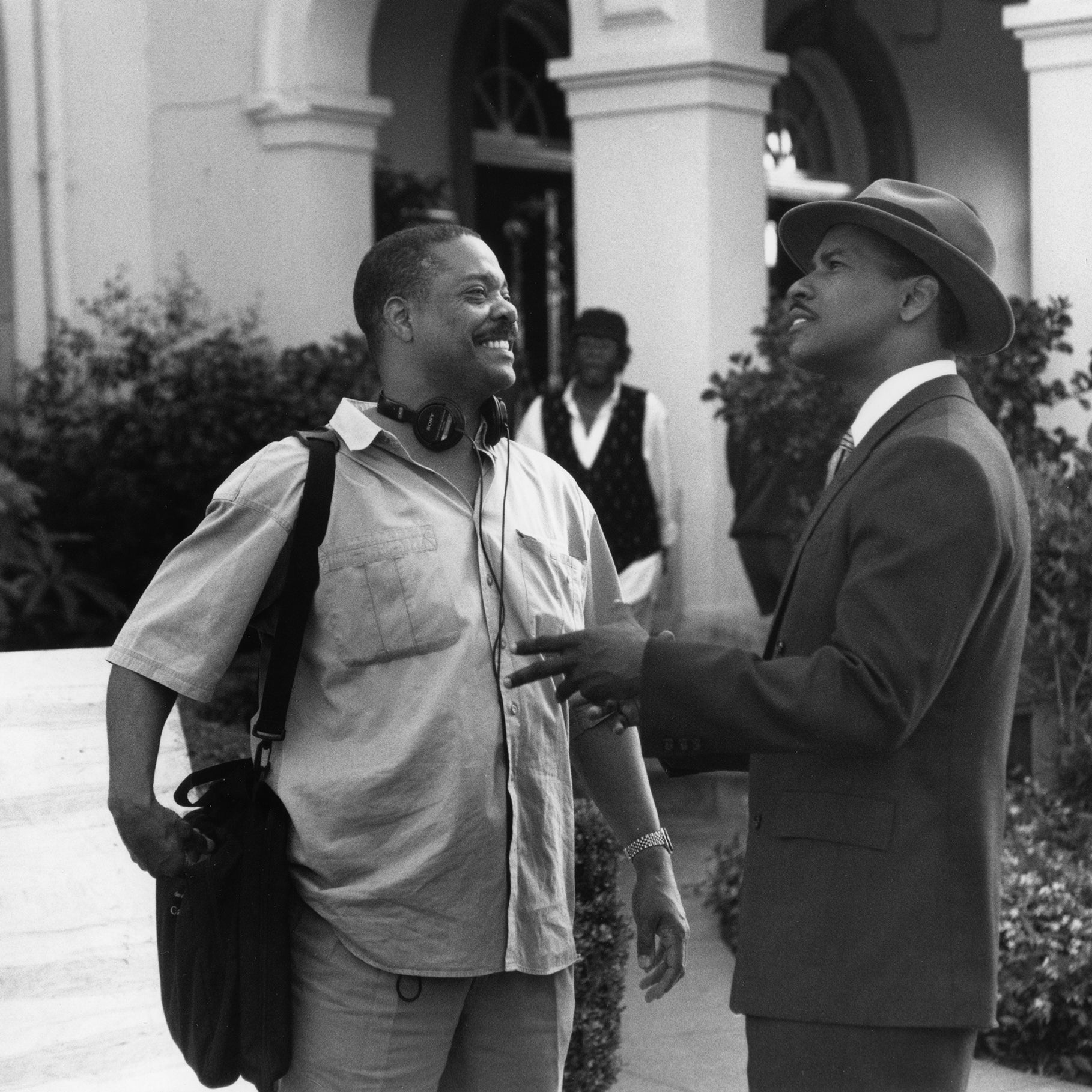

The film’s writer–director, Carl Franklin, started out as a television actor, making appearances on The Rockford Files and The A-Team before attending the American Film Institute and working with B-movie king Roger Corman. Devil was a follow-up to his breakout, the straight-to-video thriller One False Move, which was a critical and word-of-mouth hit in 1992 after Franklin and his producer convinced their distributor to release it in theaters in three cities. In honor of Devil’s entry into the Criterion Collection, I talked to Franklin about the appeal of 1940s Black community, the way a Black private eye complicates the noir tradition, and how the O.J. Simpson verdict helped scuttle his movie. Our conversation has been edited and condensed.

Dan Kois: One False Move was the first time that I saw your work. It sort of seemed to come out of nowhere. Did you think of that movie as a surprise hit? How did making that movie affect your career?

Carl Franklin: That movie is responsible for any career that I have, quite frankly. I mean, it was a surprise. Originally, we were hoping to get a theatrical release. But the company that funded the movie was a straight-to-video company, basically, their paradigm was not to release in theaters.

Right.

So what happened was, the woman who became my wife, who actually produced it, Jesse Beaton, she got it booked with film festivals. Roger Ebert saw it. [Los Angeles critic] Anne Thompson saw it. And [Seattle Times critic] John Hartl saw it.* And they all really liked the film. And what she said to them was, “If you can give it a bit of a release, you’ll have strong reviews in Seattle, in Los Angeles, and in Chicago. You could put those quotes from those reviews on your VHS boxes and sell more units.”

Wait, the pitch was, “Just give these guys a chance to write something nice about your movie so that you’ll have something to put on your VHS box”?

Exactly. That was the pitch. I think they may have given it a week or something like that. It caught on. I mean, it was incredible that summer, when it was just gaining all that momentum. It was like … something in the movies.

So then you’ve had that experience, and you’re trying to figure out how to capitalize on it, I presume, as a writer–director. How did you end up with Devil in a Blue Dress as your next project?

Everyone was telling me that I shouldn’t do a movie with a Black lead. Because there was no money behind One False Move, no one knew who I was, and they assumed I was a white director. No one knew anything about me, and they didn’t connect me with my acting career, which hadn’t been that noteworthy. They just assumed I was white.

When people would tell you something like that, like, “Maybe you better not do a movie with a Black lead right now if you’re trying to build your career,” I mean, did that scare you off in any way?

I just thought, “This is what I want to do.”

How did it become a reality?

Universal had the rights. Jonathan Demme, who had a deal at TriStar at the time, contacted me and asked me what I wanted to do, and he would executive produce. Denzel was interested in the books already. He and Wesley Snipes both were interested in the books. I said to Jonathan this was what I would like to do. So they went about getting the rights to it and getting it over at Sony.

And Jonathan had a relationship with Denzel already because of Philadelphia.

In fact, when I met Denzel, it was on the set of Philadelphia, in Philadelphia.

Well, you got to see him in a suit, so you knew that that would work.

Exactly.

What was it about this particular era in Black American life that was interesting to you, the ’40s, particularly?

That was the generation that was right before I was born, actually. I was born in 1949. That era was something that was alive in my household. These were people who were directly from the South, who were transplanted from Texas and Oklahoma and Louisiana. There was a lot of freedom in it, and there were still those real strong values. Everybody looked out for you. You didn’t worry about anyone harming you or anything in your community there. You’d hear all of that barrelhouse music. That whole Southern culture was something that was kind of a nostalgic thing for me.

And I’ve been a fan of those noir movies, man. I mean, I loved those. Anything with Humphrey Bogart, I was going to watch it. I had read some Dashiell Hammett, some Raymond Chandler, and I kind of was drawn to that kind of compromised world that film noir deals with.*

Those heroes are marginalized in some ways, but they can still navigate white society with ease.

Right.

And a Black detective has a whole different set of problems.

It gives you another obstacle. Of course, obstacles are the key to drama. If it was a Sam Spade character, you know there’s going to be the one cop who’s going to be cool with him, and the other cop is going to want to break his neck. In Easy’s case, both cops want to break his neck. And also, just certain areas of the city, there were sundown laws in certain places. He really should not have been out in Malibu.

How did Denzel approach the role? It seems like a little bit of a different kind of character for him at the time.

Denzel is a stickler for research. So he went down to the Fifth Ward in Houston and mingled around with those folks, heard their speech patterns. And Denzel’s a guy who, he wanted his wardrobe ahead of time so he could wear it, not as a costume, but just wear it around and get used to kind of sinking into the clothes and what that does to you in terms of your personality. He and I talked a lot about different things that were going on at that time and got pretty close in terms of just collaborating.

I mean, he was the first real A-lister you had worked with. Did he throw his weight around on that set? Did he cause problems?

He was one of the players. He was part of the ensemble in some ways. I mean, he was the lead, but he’s an actor, and he appreciated the fact that there were other actors on the set. He’s got an A game that he brings. I don’t know. Maybe because it was new, his stardom. I think he’d already won an Oscar, supporting actor, on Glory, but he wasn’t doing the star trip. He was pretty down-to-earth on that film.

How did Don Cheadle get involved? This was the first time I had ever seen him in anything.

I had had Don in my thesis film at the AFI, so I was aware of him. But the problem was, there’s 10 years’ difference in his and Denzel’s ages. Denzel had just come back from … He had this kind of tradition where he and his family would get a yacht with another family, and they would cruise the Mediterranean for summer vacations, with the children and everything. And so he’d come back from vacation, and he had put on some weight. He had a big beard. I just thought, “God, the age difference. I just don’t know about that because they’re supposed to be contemporaries.”

Right.

And Denzel kept saying, “Dude, I’m going to be young. Tell him I’m going to be young.” And when it was time to shoot—he was young. We brought Don up a little bit in age. So he just knocked it out. He was just so good.

Well, it’s such a funny character, who just shows up and raises hell and then takes off. Why is he important to the story?

He’s kind of the alter ego of the Easy Rawlins character. In the book, Easy, who’s experienced World War II, and has had to kill, and has had to see a lot of killing, he’s had it with that. He doesn’t want to get his hands dirty, doesn’t want to deal with that element in life. And so he’s a guy who actually is wrestling with his conscience in terms of violence. And then there’s this other guy who has no problem with that.

Mouse does not wrestle with his conscience at all.

Exactly.

So the movie comes out. It gets great reviews. It does not make back its budget. Why did that happen?

Couple things. Number one, the genre. The gumshoe genre is a tough genre. Two, the O.J. Simpson case was … We opened on Friday. They announced on Friday that they were going to come with a verdict. And here we had this Black guy looking for a white woman, and that, I think, was in the trailer.

Oh no.

So there was that. And there’s also, there was not a lot of interest on the part of the studio to promote the movie, because the executives who had green-lit the film were no longer there.

The impression I had always gotten over the years was, yeah, that it hadn’t been promoted, and the release had basically been botched. And I just think of these cycles we go through of studios blowing off the Black audience and then rediscovering the Black audience. And I’m trying to figure out where we were in that cycle in 1995.

Yeah. Yeah. There was still the kind of belief that Black material didn’t translate internationally that has since been debunked.

It always struck me as a real shame because it seems obvious to me that this movie is the beginning of a franchise, or it should have been. And so I have this version of a better Hollywood in my brain, where we got three or four more Easy Rawlins mysteries, with Mouse showing up to raise hell. Was that the goal?

When Sony bought the rights, they got all three books that were out at the time. So the intention was for it to be a franchise. However, that idea kind of evaporated due to the box office. Now, there have been rumblings. There’s been interest, I’ve heard a few different times, for it to become a television series. But nothing so far has materialized.

Slate receives a commission when you purchase items using the links on this page. Thank you for your support.

There are Easy Rawlins books set in the late 1960s. Denzel’s only a little bit old, and I bet he could make himself young for you again. You should give it one more shot.

Yeah, we should. I’ve still got his number.

Correction, July 25, 2022: This piece originally misspelled the last name of author Dashiell Hammett.

Correction, July 22, 2022: This piece originally misspelled the last name of the late Seattle Times film critic John Hartl.