When the Tall Tale Grew Bigger

50 years ago, Thomas Berger's novel Little Big Man was unfairly dismissed as lowbrow. But as its stature grew, it boosted critical acceptance for other westerns, too.

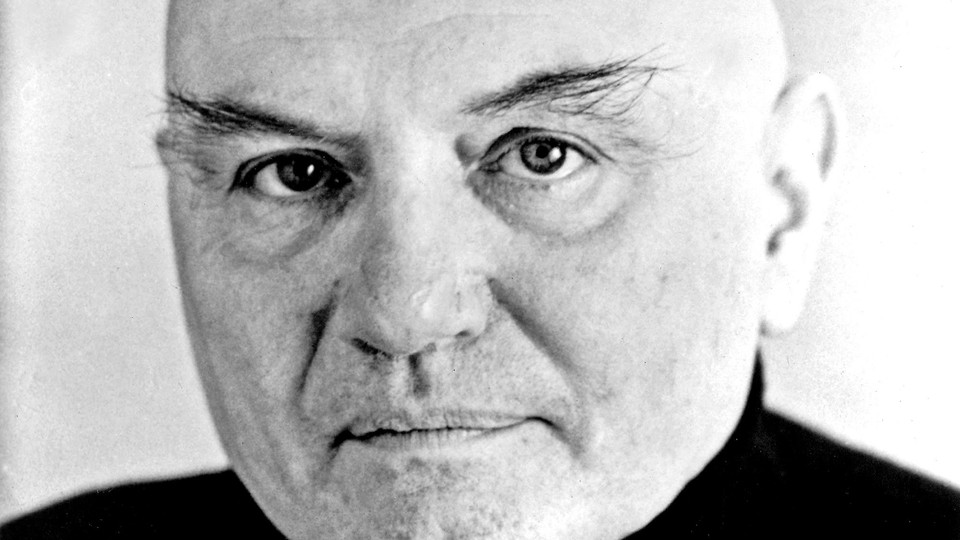

In a fairer world, Thomas Berger, who died in July at the age of 90, would have lived to see his great novel, Little Big Man, reprinted on its 50th anniversary. But then, in a fairer world Little Big Man would be widely thought of as a contender for the Great American Novel, not merely the as inspiration for a popular 1970 film.

I’ll leave it to future literary critics to determine why Berger, the author of such wonderful novels as Crazy in Berlin (1958), Reinhart in Love (1962), Vital Parts (1970), Neighbors (1980), and The Feud (1983), wasn’t given his due. Some of his supporters insist that it was his refusal to cultivate the New York literary crowd; Richard Snow, former managing editor of American Heritage and a longtime friend of Berger, recalls that he tried unsuccessfully for years to get Berger to attend book parties and literary luncheons. Others thought it was because he wrote several novels that were pigeonholed as “genre” fiction (i.e., crime novels, sci-fi, even fantasy). In the Paris Review obituary for Berger, Dan Piepenbring addressed both when he wrote that the author “who spent most of his life diligently removed from public life, seemed to submerge himself in a goulash of genre fiction.”

Dismissively reviewed by the New York Times and ignored by most others upon publication in 1964, Little Big Man metamorphosed, over the decades, into a cult classic, largely due to the influence and passion of the few fans it had. Ralph Ellison championed it to his fellow National Book Award judges (alas, they felt that westerns need not apply). Henry Miller, in a letter to Berger’s publisher, called the novel “an epic, such as Mark Twain might have given us, a delicious, crazy, panorama enlargement …” by which, presumably, he meant a tall tale.

Celebrities from Janis Joplin to Marlon Brando (who wanted to make it into a film but couldn’t get backing after the disaster of Mutiny on the Bounty) raved about the book. John Cheever told Berger that on a visit to the USSR in the ‘80s he saw that “everyone at the University of Moscow was reading Little Big Man.” A piece several years later in the Times had a different tone than the paper’s original review, calling it “the very best novel ever about the American West.”

I think Larry McMurtry gets it about right in his introduction for the 50th-anniversary edition. He calls Little Big Man “an American masterpiece, up there with Hemingway and Twain.”

* * *

Little Big Man purports to be the memoirs of a 111 year-old frontiersman, Jack Crabb, who was discovered in a nursing home by a self-proclaimed “Man of Letters,” Ralph Fielding Snell (the middle name is almost certainly a nod to the author of Tom Jones, one of the creators of the picaresque novel). Snell isn’t sure how much trust to put in Jack’s tales of his frontier adventures and notes Crabb was either “the most neglected hero in the history of this country or a liar of insane proportion.” Jack makes no apologies for the incredulity of his story: If you don’t believe him, “you can go to hell.” Snell is sure thing of one thing: Crabb was “the foulest-mouthed individual of whom I’ve ever had experience.”

Jack has been called the Zelig of the Old West, but he was much more. He was the only white survivor of Custer’s Last Stand in 1876, a witness to what came to be called the gunfight at the O.K. Corral in 1881 (according to Jack, a drunken and belligerent Doc Holliday started it all), and, finally, the murder of Sitting Bull by Indian agency police in 1890. He toured the U.S. and Europe with Buffalo Bill Cody, Sitting Bull, and their Wild West show. (The cover of The Return of Little Big Man is an actual photograph taken on the Grand Canal in Venice of Cody, Chief Bull, and an unidentified white man who Berger always insisted was Jack.)

He was a participant in many of the West’s famous events, fighting on the side of the Seventh Calvary at the Little Big Horn, and he was on a first-name basis with many Old West legends from Wild Bill Hickok to Wyatt Earp, whom he offends by belching—Earp thought Jack was mocking his name. (“When he looked at you as if you were garbage, you might not have to agree with him, but you had sufficient doubt to stay your gun hand.”) Earp “buffaloes” him, slamming the barrel of his gun across Jack’s head.

Orphaned at the age of 10, Jack was raised by the Cheyenne, but, as he tells us in his opening sentence, “I am a white man and never forgot it.” Berger researched his Plains Indians tribes assiduously, but never made the mistake of claiming to know them, judge them, or explain; he told me in an interview for American Heritage in 1999, “Indians simply never understood whites, and vice versa.”

After arguing with one of his Cheyenne relatives on the greatness of the “Human Beings,” as the Cheyenne referred to themselves, Jack’s racial chauvinism shows through: “Whenever I ran into their arrogance, it served only to remind me I was basically white. The greatest folk on earth! Christ, they [Indians] wouldn’t have had them iron knives if Columbus hadn’t hit these shores.”

Compared to the soggy piety of many white writers’ accounts of native cultures—think Dances With Wolves—Jack’s crusty skepticism in Little Big Man has struck many American Indian writers such as Vine DeLoria, Jr. and Sherman Alexie as refreshing. In Little Big Man, Berger, using Jack Crabb for our eyes, imagines cowboys and Indians not as members of a conquered or conquering race but as heroes in the Greek sense—though some, like Wyatt Earp, are a little less Greek than others.

For instance, Buffalo Bill Cody’s stock doesn’t sell for much today with historians who seeing his Wild West show as a spectacle that exploited and degraded Indians. But Jack comes to admire Bill for “his personal style of being the center of attention without lowering the value of those around him, which was the manner of an Indian chief.” Jack is open-minded enough to draw an interesting comparison between Custer, whom he did not like, and Sitting Bull, whom he loves: “The attitude he [Custer] had of regarding as pathetic everyone who could not be Custer stood him in good stead at the end. So with Sitting Bull.”

Jack sees them all as larger than life because that’s the way everyone around them saw them—it might even be the way they saw themselves.

Perhaps the reason the American literary establishment was so slow to come around to Little Big Man was its subject matter. It’s a curious fact that for most of the 20th century, the Old West was seldom regarded as a serious literary subject. Except for a handful of stories by Bret Harte and Roughing It by Mark Twain—new journalism before “the new journalism”—the West inspired little work that rose above the level of regional interest. (Some would argue a case for Owen Wister’s 1902 novel The Virginian, but its stilted prose and stuffy late-Victorian morality rate mostly guffaws today.)

The most well-known authors of books on the West were the 20th century’s Zane Grey and Louis L’Amour, the latter of whom at one point was considered the most popular writer in the world. But even their best books often seemed more inspired by decades of western movies than by the real West. Wallace Stegner established a genuine reputation as a writer of both fiction and nonfiction (and also as a staunch environmentalist), but it wasn’t until he won the Pulitzer Prize in 1972 for his novel Angle of Repose, 35 years after his first book was published, that he began to garner real critical attention.

In An Introduction to American Literature (1967), Jorge Luis Borges summed up typical critical attitudes towards the genre: “Compared to ‘poesia gauchesca’ [poetry inspired by the gauchos in Argentina], the North American western is a tardy and subordinate genre.” He was also disdainful that the hero of western novels was invariably limited to “the profession of sheriff or rancher.”

Borges should have liked Little Big Man, then. The glory of the book lay in how it broke many of the rules of fiction about the frontier West. In Little Big Man and the sequel, The Return of Little Big Man, sheriff and rancher are about the only two occupations that Jack Crabb never got into. Among other jobs, Jack was a gambler, muleskinner, buffalo hunter, freight hauler, snake-oil salesman (literally), Army scout, gunfighter, storekeeper, assistant preacher, and even a Northern Cheyenne warrior. After all, what is the point of the frontier if not to reinvent oneself?

As Little Big Man's stature grew over the years, it paved the way for critical acceptance of other serious writers who took the Old West for a theme. I’m thinking of Charles Portis’s True Grit (1968); Michael Ondaatje’s poem cycle, The Collected Works of Billy the Kid (1970); Ron Hansen’s Desperadoes (1979), about the Dalton Gang and The Assassination of Jesse James by the Coward Robert Ford (1983); Cormac McCarthy’s apocalyptic Blood Meridian (1985); Pete Dexter’s elegiac twilight-of-the-Gods novel of Wild Bill Hickok’s last days, Deadwood (1986); Daniel Woodward’s unsparing vision of internecine warfare in Civil War-torn Missouri, Woe to Live On (1987); M. Scott Momaday’s The Ancient Child (1989), which juxtaposes the legend of a young Kiowa boy with the legend of Billy the Kid; Robert Coover’s phantasmagorical Ghost Town (1998); and Philip Kimball’s sweet, sad and savage Liar’s Moon (1999). Taken together, these books constitute the golden era of the western.

I left one book off that list—Berger’s 1999 sequel, The Return of Little Big Man, which, sadly, is out of print. In its final chapter, Jack watches Cody’s reenactment of Custer’s Last Stand, and muses, “I could start my own exhibition just on the basis of places I’ve been and the famous people I knowed at the most important times so far as history goes.”

So he could, and so Thomas Berger did.