Hong Kong’s first chief executive Tung Chee-hwa takes a trip down memory lane

Two decades after Hong Kong’s return to Chinese sovereignty, the former shipping tycoon relives some watershed moments, from the handover to his time in the US and the year his company almost went bankrupt

The raising of China’s national flag over Hong Kong 20 years ago was witnessed by 4,000 dignitaries and will, for a variety of reasons, live long in the memory of all those who were in the city at the time. But when the party was over and the last British governor, Chris Patten, had bid an emotional farewell, the responsibility for making a success of Hong Kong’s return to China lay primarily on the shoulders of one man.

Former shipping tycoon Tung Chee-hwa was seen as a surprise choice. A low-key businessman, rather than a civil servant or politician, he had seemingly emerged from nowhere to become the city’s first chief executive.

An interview with Tung to mark the 20th anniversary of the handover provides an opportunity to reflect on the life of a man who was born in Shanghai, went to school in Hong Kong, studied at university in Britain and worked in the United States before returning to the city he calls home.

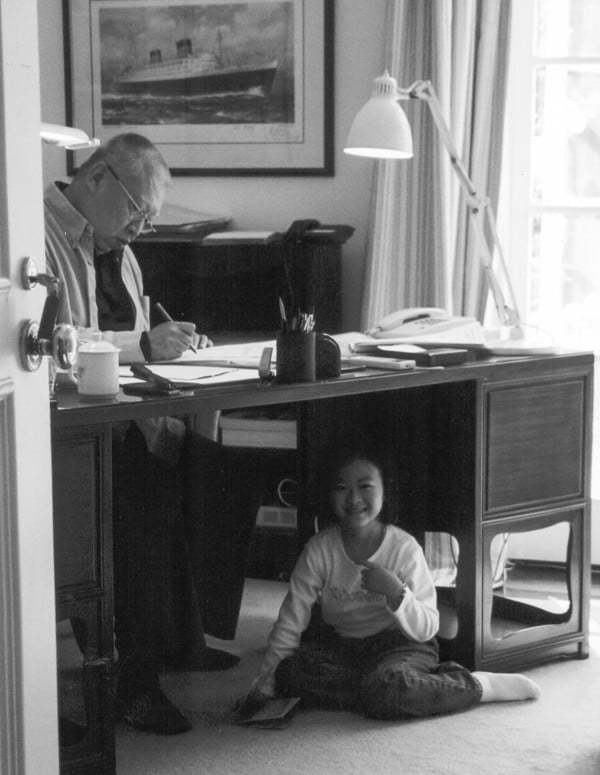

Tung will this week celebrate his 80th birthday but remains as busy as ever – and is in combative mood.

“Learn from me,” he says, thrusting his hands forward as he explains why he continues to have great confidence in the future of Hong Kong, China. His belief in new leader Carrie Lam Cheng Yuet-ngor is rammed home with a clenched fist.

His memories of the big night in 1997, however, are a little hazy.

“It was raining, raining a lot,” he remembers. “I didn’t get any sleep that night.”

Britain’s Prince Charles, it was later revealed, described the Chinese officials present at the ceremony as “appalling old waxworks”.

Tung saw them differently: “They were dignified. It was a very solemn moment, you see.”

So much has happened over the past two decades, it is difficult now to recall the cautious optimism with which Hong Kong people greeted the new era, under the novel concept of “one country, two systems”.

I decided to run [for chief executive] because of my sense of mission. My father always taught me to do meaningful things and to be proud of being Chinese

“Cautious” and “optimistic” are two words Tung has often used to describe himself and, at the time of the handover, he had every right to be optimistic; his public approval ratings were so high they would make his successors green with envy.

However, Tung’s administration would face a series of unique challenges: the Asian financial crisis; the severe acute respiratory syndrome epidemic, which claimed 299 lives in the city; and an ill-fated attempt to push through national security laws. His popularity plummeted and, by 2003, protesters were shouting, “Down with Tung” at demonstrations that were drawing up to half a million people.

He resigned less than two years into his second term, citing health reasons and an onerous workload. But his departure is widely believed to have been triggered by Beijing.

Tung’s appointment as a vice-chairman of China’s top advisory body the same year was seen, at the time, as a consolation prize. But he has become an increasingly important adviser to the central government, especially on relations with the US, and his emotional appeal to demonstrators during the 2014 Occupy pro-democracy protests proved, if nothing else, that his confidence had returned.

The venue is a poignant one, given that this is an interview to mark the anniversary of the handover. We are shown into the drawing room at the Office of Former Chief Executives, in Kennedy Road, a beautiful Renaissance-style building that was a colonial villa and school. The Sino-British Joint Liaison Group, responsible for thrashing out details of Hong Kong’s transition to Chinese rule, used to meet in this room, in which three sofas and two armchairs form a square.

I half expect cocktails to be served, but the people wandering in and out as we wait for the interview to start are builders undertaking renovations. (Perhaps they are making room for recently departed leader Leung Chun-ying.) The national and Hong Kong flags standing rather incongruously in the corner and the Bauhinia plaque on the wall are reminders that this is no ordinary drawing room.

Tung smiles warmly as we shake hands. He seems to have aged well.

Our armchairs are angled towards each other; it feels a little like one of those formal occasions in Beijing when the president sits for a scripted chat with a visiting official. But Tung is relaxed, even jolly, as I seek to take him on a trip down memory lane.

He was born in Shanghai in 1937, at a time of great turbulence in China. His early years coincided with war against the Japanese and conflict between Communists and Nationalists.

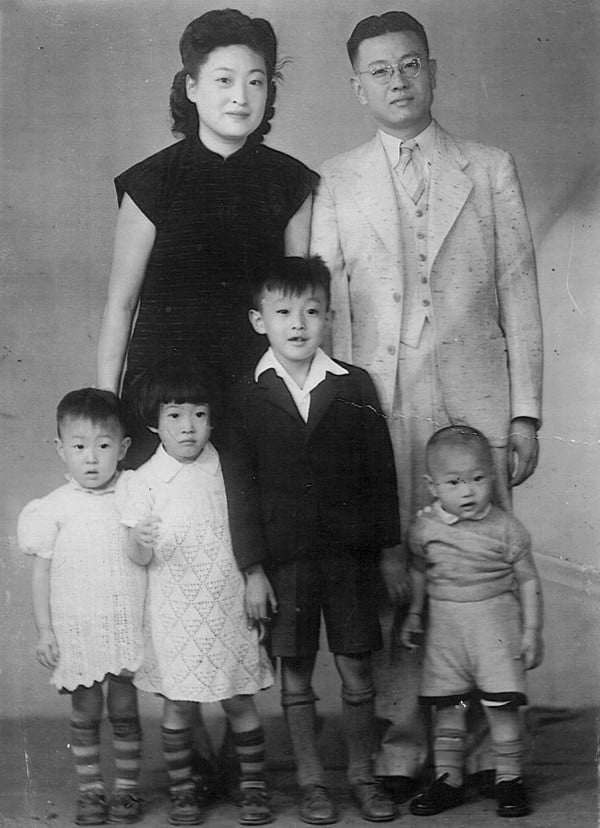

His background was, he says, with some understatement, “sort of middle class”. His father, Tung Chao-yung, was a shipping magnate who, by the 1940s, had established companies in Hong Kong and China. The family firm, the Orient Overseas group, was to become one of the biggest shipping companies in the world.

Tung Jnr says he was sheltered from the troubles that beset the country in his youth, “but I can vividly remember when a Japanese – no sorry, I think it was an Allied aeroplane – flew over Shanghai. We all had to hide underneath the dining table”.

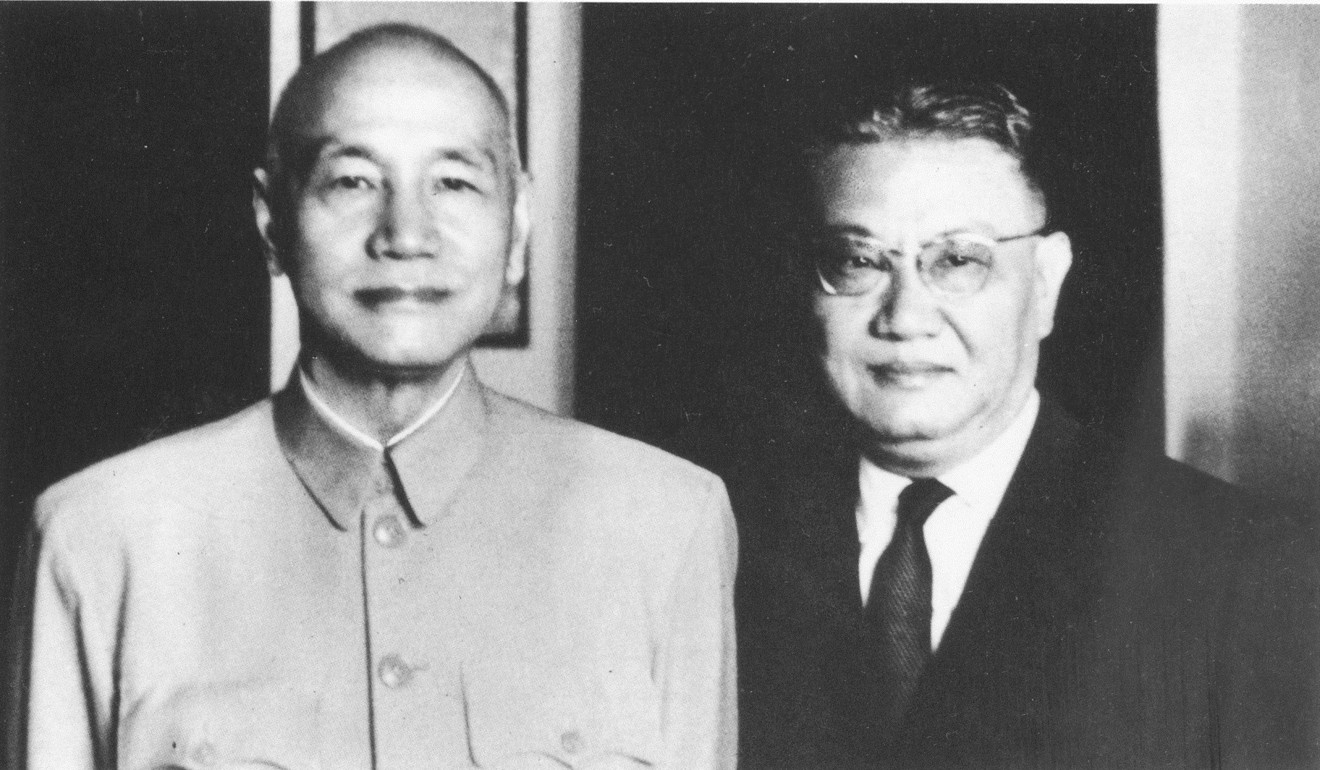

He recalls going to a “very good school” near his home in the city but, as the Communists came to power, his family had to leave Shanghai. His father was on good terms with Nationalist leader Chiang Kai-shek and, through his shipping business, was to play a pivotal role in the early development of Taiwan, helping to keep the Nationalist bolthole supplied.

The 11-year-old left his childhood home and headed to the city he would later lead. The family travelled – not surprisingly – by ship, a journey that took four days and three nights.

“Such a beautiful harbour,” he recalls of his first sight of Hong Kong. His father, though, had already established himself in the city.

“My late father was a shipping person,” says Tung. “His head office was in Shanghai. He was full of global vision and what shipping was all about. So, in the 1930s, we had already bought a house in Kowloon Tong. It cost HK$3,000. It was at 27 Stafford Road.”

Then, he was sent to Royden House, an international school on Caine Road, to learn English in preparation for an education in Britain.

“My father was saying, ‘CH, your intellect, you can’t get into HKU [the University of Hong Kong] because you are not smart enough. I don’t have the influence to persuade friends to get you into HKU.’”

So Tung set off for England, with his father warning him: “If you don’t get into university, don’t come back.”

First, he studied in Tunbridge Wells, and enjoyed cycling through the “beautiful” Kent countryside. Then, he was off to Bournemouth, on the south coast, to take O- and A-levels. Finally, he secured a place at the University of Liverpool, to study engineering.

“I suppose I did work hard,” he says. There was no time for parties or girls, he recalls, before his girlfriend, now his wife of many years, Betty, moved from Hong Kong to join him.

He did find time for soccer, though, watching both Liverpool and their city rivals, Everton, before plumping for the Reds because he enjoyed the atmosphere at their Anfield ground. Liverpool went on to become the most successful team in the country – and then Europe – but when Tung started supporting them, in the ’50s, they “were in the second division and they were struggling”.

“I am still a Liverpool fan, but I am going to give up,” he jokes. It has been 27 years since Liverpool last won the league title and Tung is clearly still disappointed about the club’s decision to sell striker Luis Suárez to Barcelona, in 2014. “It was the best chance they had to build a generation,” he says.

After graduating, Tung moved to the US.

“My late father had his very special views. He said, ‘CH, the United States is about the future, so go and learn as much as you can about what the future is going to be like.’”

He spent nine years in Boston and New York and it was sport rather than American culture in general that appealed; Tung developed a liking for the Boston Red Sox (baseball) and the Boston Celtics (basketball).

“I am following them today but, like Liverpool, I’ll have to wait a long time before they will become champions.”

After working for General Electric, Tung joined the family shipping business in New York.

“That was always the plan. All the way through, my mother left me in no doubt that as soon as I was ready, I was to come home and help my dad,” he says.

He would return to Hong Kong in 1969.

It has been said that Tung’s experiences in the US made him wary of protests.

“There were a lot of protests against the Vietnam war in those days. In my view, there was a huge change in the attitude to some of these values. There were lots of demonstrations, which made people think about what is right and what is wrong.”

But it was in Hong Kong that Tung faced a crisis that, perhaps more than anything else, has shaped his outlook. He took over the family business when his father died, in 1982. Three years later, Orient Overseas was on the verge of collapse, with debts of US$2.68 billion. Tung fought for almost two years to save the business before the company was bailed out, with US$120 million of the funding, including investment from China, coming from a consortium led by tycoon Henry Fok Ying-tung.

“It was a very difficult and trying time,” he says now. “It was also a very unique experience, as I was able to bring the company around and make it into a success.”

Before the bailout “nobody would say, ‘CH, you have a chance.’ I always insisted that I had a chance. The point is, one always has to be optimistic, realistically optimistic, and just struggle and fight for it.”

As Tung struggled to save his family business, the people of Hong Kong were preoccupied with other matters. The Sino-British Joint Declaration was signed in 1984, paving the way for the city’s return to China. It was that agreement that stated Hong Kong’s leader would be called the “chief executive”.

The earliest indication, perhaps, that Tung may be the first holder of that title came when he joined Patten’s Executive Council, in 1992. The governor wanted a businessman on his team, but also someone who could represent China’s interests. With his business contacts and the trust of Beijing, Tung fitted the bill.

In June 1996, “China’s spy in Exco”, as he was dubbed by some, resigned, citing a conflict of interest after becoming a member of the Beijing-appointed Preparatory Committee, preparing for the handover.

By then, though, it was well known he was in the frame to become the inaugural chief executive of Hong Kong. The South China Morning Post first mentioned him as a contender in November 1995, around the time Chinese officials had started talking of a “dark horse” candidate.

Confirmation that Tung was indeed Beijing’s choice came the following January, in the capital’s Great Hall of the People. President Jiang Zemin sought out Tung at a gathering and warmly shook his hand, which was widely seen as evidence the shipping tycoon was “the anointed one”.

Tung insisted at the time that it was “just a handshake”. Asked now if he, like everyone else, knew what the handshake meant, he protests, “No, no, no, no. I don’t think so.” Tung senses my scepticism. “No, seriously!”

It was Run Run Shaw, the entertainment mogul and philanthropist, who first raised with him the idea of leading Hong Kong, he says.

“He was a very good friend of mine and a very good friend of my father. We talked to each other from time to time. He called me on a Sunday in 1995 and said, ‘I will come to talk to you.’ I thought, ‘Wow, that’s a big thing.’ I called him Runcle.

“He came to see me in my office. He sat down and spoke to me in Shanghainese. He said, ‘Heh, I think you are going to be CE.’ I said, ‘What? Come on, you are kidding. I am so busy with my business. I don’t know anything about that stuff.’”

Tung did not declare his interest in standing for selection until September of the following year. He described himself as a reluctant candidate because he would not be able to spend so much time with his grandchildren (he now has nine).

In November 1996, he said, “I have thought a long time about what I can do for Hong Kong and whether I can take the post. I decided to run because of my sense of mission. My father always taught me to do meaningful things and to be proud of being Chinese.”

Proud of being Chinese he may be, but his three children – Alan Tung Lieh-sing, Andrew Tung Lieh-cheung and Audrey Slighton Tung Lieh-yuan – possess Americans passports, because, he said in 1997, they were all born in the US. I ask him about his family, but he would rather talk about Hong Kong-Beijing relations.

Tung won 320 of the 400 votes available from members of the Selection Committee in December 1996. A Chinese University poll at the time revealed 64.9 per cent of respondents believed he was the right man for the job.

The next six months were spent preparing for the handover and all that would follow.

Controversial was the establishment of the provisional legislature, which was seen as being of dubious legality. It sat in Shenzhen until its members were sworn in early on the morning of July 1, 1997 (a ceremony several foreign officials boycotted in protest). The news that the People’s Liberation Army would send 4,000 troops across the border at dawn on that day, some in armoured cars, also raised concerns. Meanwhile, there were fears of protesters clashing with police.

In the end, though, the handover was a peaceful one.

His schedule on the last day of British rule and the Hong Kong SAR’s first was punishing, says Tung. There were meetings with foreign officials, state leaders to greet at the airport, a lavish banquet to attend, the handover ceremony itself and then the swearing in and passing of laws in the early hours. Reports in the Post at the time described him as being “tired, but jovial” and “tired, but relaxed”.

Had he been worried that something would go wrong?

“No, no, no. I was very proud that Hong Kong had returned to China under a situation where the two sovereigns were still good friends. It was really quite wonderful.”