In this mini-series, we return to movies and TV we’ve loved to see how they depict gender. Does it hold up in 2019? Warning: contains spoilers.

When was this film released? 1994

How does it hold up? Not well

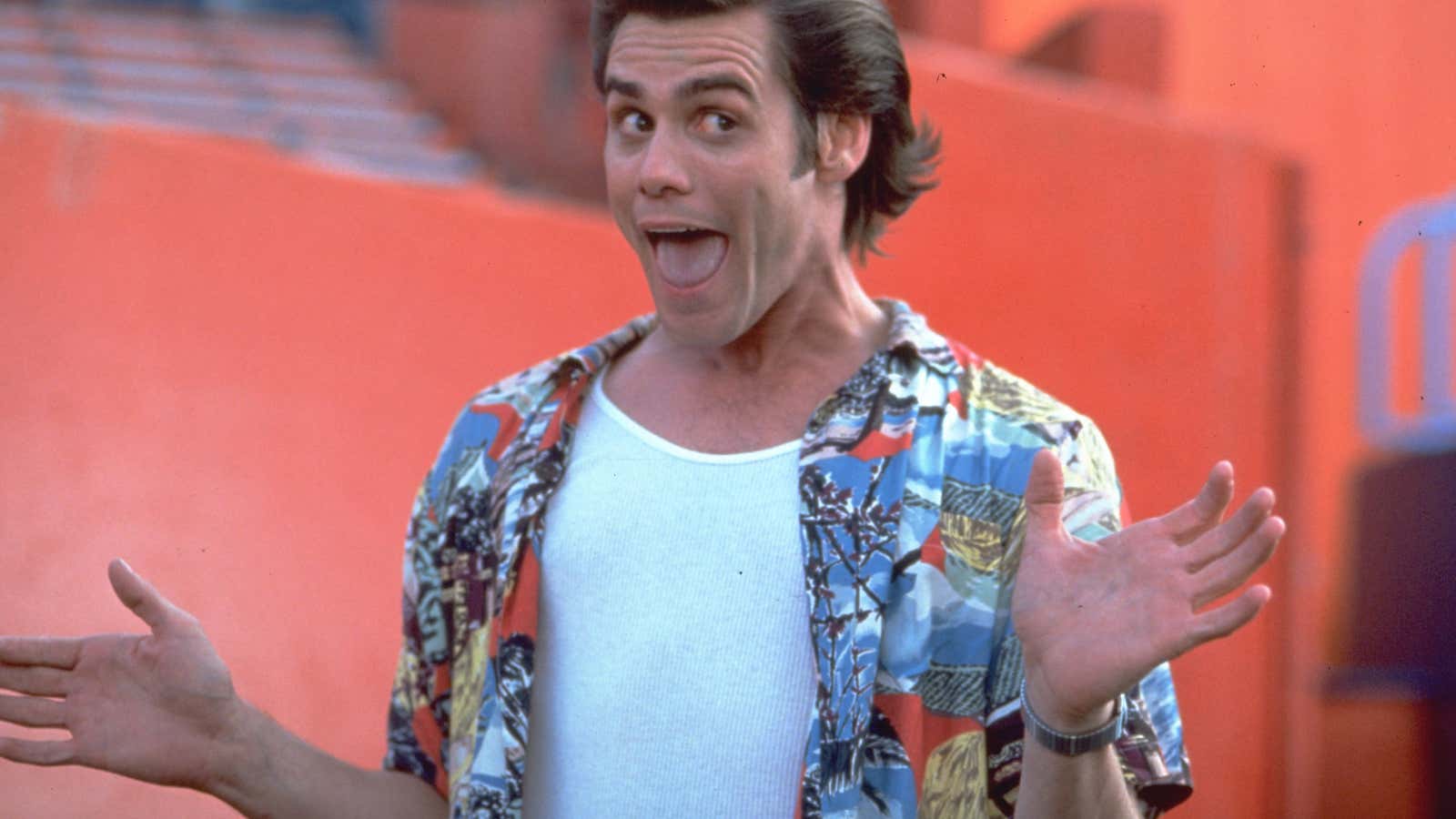

Ace Ventura: Pet Detective catapulted Jim Carrey to stardom. Released in 1994, the movie was a surprise hit. It cost only $12 million to produce (in 1994 dollars), and made over $100 million at the box office. The comedy brought the sayings “All righty then” and “Loooooser” into common parlance—at least among American teenagers of the time.

That included me. Watching the movie again recently as a 35-year-old, I found it charming, if not as hilarious as I did when I first saw it at 10.

But it was also deeply disturbing. Its blatant homophobia and transphobia were common for the time, but appear backward—and damaging—in a more politically-correct era.

Carrey plays Ace Ventura, the eponymous pet detective. The plot is centered around his efforts to find a stolen dolphin owned by Miami Dolphins football team. Ventura’s methods are… unusual. He can communicate with animals, and behaves outlandishly, which leads people to underestimate him.

The central reveal of the movie is that Miami’s female police Lieutenant Lois Einhorn is the one who stole the dolphin. Ventura has an antagonistic relationship with Einhorn with some sexual undertones (she kisses him in an early scene). It turns out that, a decade earlier, she was the kicker for the Miami Dolphins before transitioning gender, and she stole the dolphin out of lingering anger at the team. She had missed a game-winning kick in a Super Bowl, and blamed her teammates for her failure.

When Ventura figures out that Einhorn transitioned, he is horrified. Earlier in the film, she had kissed him. Immediately after his realization, there is a minute-long scene of Ventura aggressively brushing his teeth, plunging his mouth, and taking a shower to try to “clean” himself after having, as he thought, kissed a man.

Einhorn’s identity is later revealed to a large crowd. Everyone is disgusted. Policemen who are there to retrieve the dolphin vomit from the idea that Einhorn was once a man.

The scenes are both homophobic and transphobic. If there is one key message of the film, it is that we should be disgusted by a man kissing a woman who has transitioned.

When the movie came out, most critics hardly noticed. Of 11 mainstream reviews published at the time, most of which were negative, only two mention the movie’s bigotry. In a takedown of the film, Variety’s Steven Gaydos’ noted in 1994 that the “third-act payoff that takes the film’s generally inoffensive tastelessness into a particularly brutal and unpleasant stew of homophobia and misogyny.” In a more positive review, the Washington Post’s Desson Howe writes, “There are some unfortunate elements that were unnecessary—a big strain of homophobic jokes for one…”

Explicit homophobia wasn’t rare in mainstream Hollywood at the time. As the writer Rae Alexandra pointed out in 2017, homophobic slurs were common in the 1980s. Movies many now consider classics of the era, including Teen Wolf, Footloose, Pretty in Pink, The Monster Squad, and Heathers, all contain derogatory terms for gays. Since the 1990s, slurs have become less common as direct homophobia became less accepted. Still, situations containing “gay panic”—characters reacting horrified at the idea of taking an action that might make them be seen as gay—are rife. For example, movies like Ace Ventura, 2005’sWedding Crashers, and 2017’s CHiPs all contain obvious “gay panic” scenes.

Even short scenes in a few movies can have real effects on gay and trans communities. The Center for Disease Control (CDC) concludes that homophobia and discrimination leads to poor physical and mental health and lower incomes for LGBTQ people. Transphobia has been linked to higher levels of suicide and worse access to healthcare for the trans community. A large body of research finds that depictions of LGBTQ characters in mainstream media can affect the way certain groups view members of these communities. So we know that these movies mattered when they first came out, and still do.

Many countries, including the US, have come a long way on issues of LGBTQ rights and perception. But we today find ourselves in the midst of, a backlash against “political correctness.” Cultural critics are concerned that we have gone too far in policing speech and attitudes. Those who call attention to transphobic, homophobic or racist representation are chastised as “snowflakes” (paywall).

Ace Ventura came out only 25 years ago. Homophobia and transphobia have not magically disappeared in a quarter-century. The belief that the policing of offensive speech and actions is a bigger problem than those ideas themselves is absurd.

The undercurrents of homophobia, sometimes obvious but often subtle, persist in film today. Just like movie critics in the early 1990s, critics and casual viewers today are almost certainly ignoring messages that are causing needless harm. Critics like Aja Romano are doing the public service by pointing out the homophobia of the 2018 movie Bohemian Rhapsody. Romano points out that this movie about a gay man, Freddie Mercury, puts nearly all the focus on his relationships with straight characters, ignoring his relationships with other LGBTQ people.

The organization GLAAD monitors media depictions of LGBTQ people. They created a test called the Vito Russo as a shorthand way to examine the portrayals of LGBTQ characters in film (It was inspired by the Bechdel test, which is used to assess the quantity and quality of interactions among female characters. To pass the Vito Russo test, a film must 1) Have one LGBTQ character 2) That character must not be entirely defined by being LGBTQ and 3) That the removal of that character would matter to the plot, so that the character cannot be considered a token, and that the character is not just used, as in Ace Ventura, as a punchline.

GLAAD reviews data on how many movies pass the test every year. They found that, in 2018, 13 of the 20 major studio movies that had LGBTQ characters passed the test, better than any other year since they began tracking the numbers in 2012. Progress is being made.

Still, filmmakers should be paying attention to these recommendations and others from LGBTQ writers. If they do, we may not have to look back in shame on another Ace Ventura 25 years from now.

This story is part of How We’ll Win in 2019, a year-long exploration of workplace gender equality. Read more stories here.