Gustave Doré (1832–1883): Master of Imagination

Charles Perrault, Contes, illustré par Gustave Doré, 1862

Paris, Bibliothèque nationale de France, réserve des Livres rares

© Bibliothèque Nationale de France / DR

Gustave Doré: intimate and spectacular

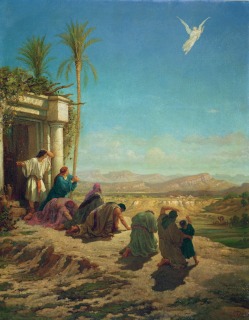

Entre ciel et terre, 1862

Belfort, collection musées de Belfort

© Musée d'Art et d'Histoire, Belfort, France / Giraudon / The Bridgeman Art Library

Gustave Doré suffered rejection at the hands of the critics of his day, just like his exact contemporary Edouard Manet. Whereas Manet became the hero of the modern age, Doré has remained for many the most renowned of illustrators, and some of his illustrations for the Bible or Dante's Inferno dare permanently etched in the collective consciousness.

His work was disseminated to an unprecedented degree in Europe and the United States, both during his lifetime and posthumously, and he was one of the great purveyors of European culture with his illustrations for major classics (Dante, Rabelais, Cervantes, La Fontaine, Milton, etc.) as well as works by his contemporaries (Balzac, Gautier, Poe, Coleridge, Tennyson, etc.).

There seemed to be no limits to Doré's creative talents; a draughtsman, caricaturist, illustrator, watercolourist, painter and sculptor, he was a protean artist who worked in the main genres and formats of his era, ranging from satire to religion, and from sketches to monumental canvases.

He not only occupies a central position in the visual culture of the 19th century, but also made his mark on the 20th and early 21st century imagination, both in the comic strip medium - of which he is considered a founding father - and on the silver screen. Whatever his chosen technique, Doré stands alone among the artists of his century in revealing the rich and lively spectacle of the poetic worlds of his imagination through the prism of his "visionary eye", as if he were constantly seeking new boundaries to push back.

The Artist and Bohemians

Les Saltimbanques dit aussi L'Enfant blessé, 1874

Clermont-Ferrand, musée d'Art Roger-Quilliot

© Ville de Clermont-Ferrand, musée d'art Roger-Quilliot [MARQ]

Bohemians, travelling acrobats and fortune-tellers frequently feature in his graphic, painted and sculpted works. Doré shared a genuine interest in fairgrounds with his contemporary Daumier. An accomplished acrobat, he occasionally dressed up as a Pierrot for fancy-dress parties and biographical accounts and caricatures alike often depict the artist as an outgoing character.

Doré clearly cultivated this image of himself as an entertainer which would be to his detriment, since his agility, virtuosity, deftness and versatility were viewed with distrust by the art world in the period 1860-1870. Furthermore, his iconography of entertainers was undoubtedly related to his feeling of exclusion from the world of official painting.

Images of Hell and Death

Dante et Virgile dans le neuvième cercle de l'Enfer, 1861

Bourg-en-Bresse, musée du Monastère royal de Brou

© Photo Hugo Maertens, Bruges

In 1861, Doré was at the forefront of the Parisian art scene with his illustrations for Dante's Inferno and he exhibited at the Salon a monumental painting, Dante and Virgil, which also drew its inspiration from the work. The theme of infernal visions interested the artist throughout his career and the interrelated themes of love and death resurface on various occasions: on the death of the poet Gérard de Nerval, during the Franco-Prussian war of 1870, and after the death of the artist's mother in 1879.

Towards the end of his life, when he was prey to melancholy and occasional depression, he tackled morbid or unsettling subjects, particularly in his sculptures. During this period, Doré completed illustrations for Edgar Allan Poe's poem The Raven, depicting a writer mourning his beloved wife. This work was published in England and the United States in 1883 and 1884, but he did not live to see it come to fruition.

Doré's Sculpture

La Parque et l'Amour, 1877

Collection particulière

© Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

Doré came to sculpture late, in 1877, exhibiting Fate and Love at the Salon, with rather low expectations regarding its reception: "There will be no shortage of criticisms and attacks, as I think that there are plenty of people who will be annoyed to see me as a sculptor, but I hope that I will also have some staunch defenders". As a painter turned self-taught sculptor, he launched into this medium without prior training, but effortlessly acquired a virtuosity on a par with his skill as a painter.

The rediscovery of the original plaster version of Fate and Love allows us to appreciate his genuine talent as a sculptor.

This passion in the last years of his life culminated in ingenious and brilliant works in keeping with a formal classical tradition and a naturalism inspired by the academicism which dominated the sculptural aesthetic of the 1870s. Doré offered a variant form often inspired by complex iconography to reflect strange subject matter or a pronounced taste for unbalanced composition.

Doré's sculptures fall into two categories - large-scale ambitious or extravagant allegorical works and smaller bronzes for highquality limited editions whose disparate sources of inspiration puzzled many of his contemporaries. Doré never achieved the true recognition as a sculptor which he craved.

Religion as a Show

Le Christ quittant le prétoire, 1874-1880

Nantes, musée des Beaux-Arts

© RMN-Grand Palais / Gérard Blot

Doré's reputation as a "preacher painter" was established in the last third of his career, after his famous illustrations for the Holy Bible in 1866. A short while later, he undertook a number of spectacular religious works for the Doré Gallery in London, which he co-founded in 1867-1868.

Contemporary critics ranging from Théophile Gautier to Emile Zola all concurred that the artist's work had great dramatic, theatrical and even fantastical power, culminating in the various versions of the colossal Christ leaving the Praetorium.

CThe power of the spectacular finds its expression in the idiom of teeming figures and explains the fact that these works in which religious feeling is expressed with quasi-choreographed potency immediately inspired a variety of performances such as magic lantern shows, living tableaux and Passion plays. However, it was on the silver screen, since its beginings, that Doré's work would finally exert a major and lasting influence.

From Caricature to Landscape

"Docks de Londres", dessin préparatoire pour l'illustration de la p. 24 de "Londres : un pèlerinage" (London: A Pilgrimage) de Blanchard Jerrold, vers 1870

Strasbourg, musée d'Art moderne et contemporain

© Photo musées de Strasbourg

Prior to becoming the most renowned of illustrators, Doré began his career working as a caricaturist and for periodicals, like many young artists seeking to establish a reputation.

The famous Parisian publisher, Charles Philipon, was his first mentor and Daumier and Cham became his colleagues. He was hired under contract in April 1848, after a trial period.

Doré acquired a reputation in the publishing world with his illustrations for the works of Rabelais (1854) and Balzac's Contes drolatiques (1855). During this period, he set himself the goal of "producing a uniform collectors' set of all the great works of epic, comic or tragic literature" in outsize formats.

n the 1860s, Doré achieved international fame with his illustrations for the Holy Bible and Dante's Inferno. Moreover, he became one of the most Hispanophile and Anglophile artists of his generation and achieved considerable success in the United Kingdom through the Doré Gallery, which he co-founded in London in 1867-1868. Literary or picturesque aspects of Great Britain and Spain would provide lasting inspiration for Doré as an illustrator and painter.

Doré did not restrict himself to painting and also turned his hand first to etching and then to watercolours, sometimes on a very large scale. He exhibited regularly at the Salon in Paris and at the Doré Gallery in London.

In addition to historical, religious and genre scenes, often inspired by his illustrations, Doré, a keen mountaineer, exhibited a number of landscapes seen during his frequent trips to the Savoie and Vosges mountains, Spain, Scotland, and Switzerland in particular. He therefore became one of the foremost exponents in France of 19th century mountain landscape painting, producing spectacular and lyrical visions.

Satirical Columns and Illustrated Books

"Le danger de patiner", dessin pour l'Album de dessins, vers 1840-1842

Strasbourg, musée d'Art moderne et contemporain

© Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

As a child, Gustave produced illustrated albums and stories in the animal fable repertoire modeled on the works of J.-J. Grandville (1803-1847) and the Genevan Rodolphe Töpffer (1799-1846), whose albums or "stories in etchings" were very popular in Paris. These albums were plagiarised by the Aubert publishing house where Doré worked when he arrived in the French capital in the autumn of 1847.

SAlthough contemporary politics was focused on the revolution of February 1848 and the end of the July Monarchy, the young artist cautiously reflected Parisian life in the Journal pour rire, and revitalised the genre of storytelling through pictures.

In illustrated publications such as the Musée français-anglais edited by Philipon, Doré experimented with a variety of subjects – genre scenes, episodes from history and religious pages – which he would develop into paintings. At the same time, he was turning towards illustrating works by contemporary authors. He began by specialising in eccentric literature, then swiftly tackled French, Italian, German and Spanish classics, and English classics in particular.

His illustrations have since been disseminated internationally and are totally without precedent in the history of art and publishing in the 19th and 20th centuries.

Book Production

L'Enfance de Gargantua, vers 1873

Strasbourg, musée d'Art moderne et contemporain

© Photo Musées de Strasbourg

Two illustrated editions of the works of Rabelais, in 1854 for the publisher Bry and in 1873 for Garnier, offer an insight into the development of illustrated publishing practice in the second half of the 19th century. The 1854 volume forms part of a "European Masterpieces" collection.

By way of a frontispiece, Doré imagined Rabelais opening the pages of a very large book. This could be seen as a projection of the figure of the illustrator about to redistribute the classics of European literature ina monumental format.

The two folios which make up the second edition of 1873 are particularly ambitious, comprising 61 plates and 656 vignettes. Approximately 100 subjects were reused from the 1854 edition, along with others from Balzac's Contes drolatiques of 1855. The contract stipulated that Doré should receive 800 francs per item, i.e. 80,000 francs in total – which was a huge sum at that time.

He was responsible for all aspects relating to iconography and divided the subjects up between his engravers, who included François Pannemaker. Doré corrected the proofs submitted to him, but the wooden matrices and the metal stereotypes produced from them to facilitate reprinting remained the property of the publisher.

The Works of Rabelais cost two hundred francs for the standard edition – a very high price for the time, and twice the price of the usual volumes – and up to five hundred francs for the luxury edition on China paper. At the same time, Doré produced large watercolours which he exhibited and which accompanied the edition.

Visions of England: London and Shakespeare

Scène de la rue à Londres, vers 1870

Paris, musée d'Orsay, conservé au département des Arts Graphiques du musée du Louvre

© RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d'Orsay) / Jean-Gilles Berizzi

London, the leading industrial and capitalist megalopolis, where the social divide was widening, held a special place in the European imagination in the 19th century. Doré visited London as a "reporter" several years before the Franco- Prussian war of 1870 and his works offer a French perspective characterised by a fascination with this neighbouring country, which was different and a rival despite the rapprochement effected during the Second Empire. This perspective alternates between or interleaves what he actually saw and what he imagined.

London : a Pilgrimage was published in England initially in 1872, then reprinted in France with a new text in 1876. For this exceptional volume, which had a lasting influence on the continental European perception of Victorian London, Doré explored various districts of this "new Babylon" in the company of journalist Blanchard Jerrold, who wrote the text.

He visited its disreputable districts by night with a police escort. The work strives to represent in ink and pencil the extremes of London social life, contrasting by turn the murky underworld with the brightness of the racecourses where high society went to relax.

Illustration d'une scène de "Macbeth" de William Shakespeare, vers 1875-1877

Strasbourg, musée d'Art moderne et contemporain

© Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

A few years earlier in 1867-1868, Doré had cofounded the Doré Gallery in New Bond Street, which provided a venue to exhibit his works in London. During this period, he worked on modern and old English classics.

His illustrations for poet Alfred, Lord Tennyson's Idylls of the King received mixed reactions from British readers, who thought that the characters did not have sufficiently "English" features. Illustrations for Milton's Paradise Lost in 1866, the poetry of Thomas Hood in 1870, and then Coleridge's The Rime of the Ancient Mariner in 1876, formed the prelude to Doré's major incompleted project – an illustrated edition of the works of Shakespeare for which he planned to produce no fewer than one thousand pictures.

Don Quixote's Spain

"La Bandurria", dessin préparatoire pour "L'Espagne" de Jean Charles Davillier, 1861

Strasbourg, musée d'Art moderne et contemporain

© Photo Musées de Strasbourg

Unlike London, Spain is depicted as a wild and picturesque land; it is gothic and Moorish, a Catholic country inhabited by bandits and beggars. Many French painters and writers had travelled there since the early 19th century, including Delacroix, Nanteuil, Hugo, Mérimée, Gautier and Dumas. Exotic inspiration was overlaid with a fascination for a pre-revolutionary and pre-industrial world, which the French saw reflected in microcosm in Cervantes' Don Quixote. In Paris, the Spanish art gallery established by Louis-Philippe at the Louvre also played an important role.

Doré made several trips to Spain, and on the first of these in 1855 he was accompanied by Théophile Gautier and the publisher Paul Dalloz. In 1861, in response to a commission from the periodical Le Tour du monde published by La Librairie Hachette, he returned to Spain with Baron Jean Charles Davillier, a knowledgeable hispanophile, who wrote an account of their journey.

Don Quichotte et Sancho avec Basile et Quiteria, vers 1863 (?)

New York, The Metropolitan Museum of Art

Don de Mrs William A. McFadden et Mrs Giles Whiting, 1928

© The Metropolitan Museum of Art, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / image of the MMA

Doré's main reason for making the trip was his plan to illustrate Don Quixote: "I am therefore travelling to the homeland of this famous hidalgo to study all the places he visited and filled with his feats, so that I can produce something with a local flavour".

Cervantes' novel ranked among the most illustrated works of European literature, but Doré was determined to outdo his predecessors. The work was published in 1863 to unanimous acclaim, even from Emile Zola: "This is described as illustrating a work; I think this is rewriting it. Instead of having one masterpiece, the human mind has two".

Religion and Pathos

Le Calvaire, dit aussi La Crucifixion, 1877

Strasbourg, musée d'Art moderne et contemporain

© Photo Musées de Strasbourg

Doré began to work on religious art in the latter half of the 1850s, initially in the illustrated press. His monumental illustrated Holy Bible published in 1866 – contemporaneously with the controversy sparked by the publication of Ernest Renan's Life of Jesus in 1863 – marked a decisive turning point for him.

"Doré's Bible" would have a lasting effect on the revival of religious art in Europe in the last thirty years of the century. Never in the history of Christian art had the Bible been so lavishly and imaginatively illustrated, at the risk of causing offence to some.

The portrait at the front of the first volume depicting God standing on a cloud creating the world, which was displayed at Cassels's bookshop in London, was withdrawn after public protests.

L'Ange de Tobie, vers 1865

Collection Musée d'Orsay - Musée Unterlinden, Colmar

Achat, 1865

© Musée d'Unterlinden, Colmar, France / The Bridgeman Art Library

See the notice of the artwork

While offering a multiplicity of totally new ideas and points of view, Doré also referenced the great classics of this genre. He therefore represented Calvary in a series of scenes which in some cases were inspired by the chiaroscuro effects of Rembrandt's etchings.

While the Bible was being printed, Doré achieved some success at the 1865 Salon with the small canvas The Angel of Tobias, which was acquired by the French State. However, he did not meet with similar success at subsequent Salons. Doré knew how to exploit the very popular contemporary taste for orientalism in his religiously inspired paintings such as The House of Caiaphas (1875).

The Christian Martyrs and Calvary explore themes which haunt the work of Doré's famous fellow artist and contemporary, Jean-Léon Gérôme (1824-1904), whom he does not seem to have known socially. However, unlike Gérôme, Doré shunned narrative ellipsis and peopled his works with ethereal angels and dense crowds.

1870: Annus Horribilis

Episode du siège de Paris, vers 1871

Le Havre, musée d'Art moderne André-Malraux

© Musée des Beaux-arts André Malraux, Le Havre, France / Giraudon / The Bridgeman Art Library

The "annus horribilis", to quote Victor Hugo, was the year of the French defeat at the hands of Prussia and the Siege of Paris, followed by civil war during the Paris Commune in 1871.

Doré volunteered for the National Guard, which allowed him, in his own words, "to witness many tragedies and episodes of ruin". He therefore took up his pencil and paintbrush to bear witness and become an activist, and his sketched notes were then compiled into scenes. He captured the nocturnal, fiery atmosphere then translated these "sights" into allegorical visions.

The large wash drawings and paintings in dark or grey hues mirror the climate of war and defeat which afflicted the country and Paris in particular.

Pétroleuse, illustration pour "Versailles et Paris en 1871" de Gustave Doré, 1870-1871

Strasbourg, musée d'Art moderne et contemporain

© Musée d’Orsay, Dist. RMN-Grand Palais / Patrice Schmidt

The siege of the French capital in the autumn of 1870 inspired him to produce a group of works whose realism represented a departure from the allegorical treatment of his patriotic works.

During the Commune, he withdrew to Versailles and Doré the caricature artist resurfaced after a break lasting many years.

He was sharper than ever and everything became a target for mockery – stiff Prussians, the features of Communards and the female arsonists dubbed the pétroleuses (fire-raisers).

On 24 April 1871, he wrote to a close Alsatian friend: "Dear Arthur, I wish I had twenty pages left to tell you about all the eventful moments and anguish which we have endured for almost a month. It defies reality and this era really belongs to the realms of fiction". Doré was particularly deeply affected by the loss of his native Alsace.

Picturesque and Sublime Landscapes

Souvenir de Loch Lomond, 1875

New York, French & Company

© French & Company, New York

Doré was one of the foremost French mountain painters of the second half of the 19th century. He focused on this genre, to which he would return throughout his career, especially from the 1860s onwards, exploring every aspect – picturesque, sublime, meditative and dramatic.

Influenced both by Alexandre Calame and Gustave Courbet, Doré, an athletic and tireless traveller with a passion for mountaineering, travelled around the French coast, in the Vosges, Savoie and Pyrenees regions, as well as in the Tyrol, Switzerland, and Scotland in particular. It was in Scotland in April 1873, in the area around Braemar, Balmoral and Ballater, that he became a serious watercolour artist and a brilliant member of the Society of French Watercolourists from 1879 to 1882.

Catastrophe du mont Cervin, 1865

Paris, musée d'Orsay, conservé au département des Arts Graphiques du musée du Louvre

© RMN-Grand Palais (Musée d'Orsay) / Gérard Blot

The landscape in general, and the mountains in particular, are suffused with literary imagination. Following his trip to Scotland, he wrote to a female English friend: "I have returned impressed by this beautiful country which is so rustic and romantic".

Over the years, Doré tended to scale down the human presence in these compositions, eventually eradicating it completely. No aspect of nature escaped his curious gaze and his hand was always poised to capture a dark sky, a raging torrent, or the quality of the light after a storm, while displaying a particular fondness for nighttime or dusk views. Some of these poetic visions, which are spectacular yet dreamlike and contemplative, are considered to be among the most striking landscapes of the mid-century period. Their harmonious construction is reminiscent of Caspar David Friedrich, whose religiosity in the face of the spectacle of nature was shared by Doré.

Gustave Doré and the Silver Screen

Sleepy Hollow, 1999

© Studio Canal

According to Ray Harrihausen (1920-2013), a special effects expert in the film industry, "Gustave Doré would have made a great director of photography [...] he saw things from the point of view of the camera". Doré's work has had a permanent impact on the imaginative realm of film since its very earliest days. In return, the silver screen has etched Doré into the 20th century imagination.

Almost every film about the Bible since The Life and Passion of Jesus Christ produced by Pathé in 1902 refers to his illustrations, and every film adaption of Dante or Don Quixote has used him as a model, from Georg Wilhelm Pabst and Orson Welles to Terry Gilliam.

All films dealing with life in London in the Victorian era by directors ranging from David Lean, to Roman Polanski and Tim Burton draw on the visions in London: a pilgrimage for their sets. A large number of dream, fantastical or phantasmagorical scenes take their inspiration from Doré's graphic work, beginning with Georges Méliès' A Trip to the Moon in 1902.

Doré's primal forests, from Atala in particular, were used in the various versions of King Kong from 1933 to the 2005 film by Peter Jackson, who had already drawn on Doré for The Lord of the Rings (2001 and 2003). Jean Cocteau was also indebted to the illustrations for Perrault's Fairy Tales for his Beauty and the Beast (1945), as was George Lucas for the character Chewbacca in Star Wars (1977) and even the Harry Potter film series.

Lastly, in the realm of cartoons and animation, Walt Disney owes a huge debt to Doré, as do the directors who first brought the character of the cat in Shrek to life in 2004. It was directly inspired by Puss in Boots, the lively feline chosen as the emblem for this exhibition.