Why this Poignant Painting is One of the Most Powerful in Art History

When art, friendship and politics meet

Every now and then, a painting manages to convey a potent and convincing message in starkly simple terms.

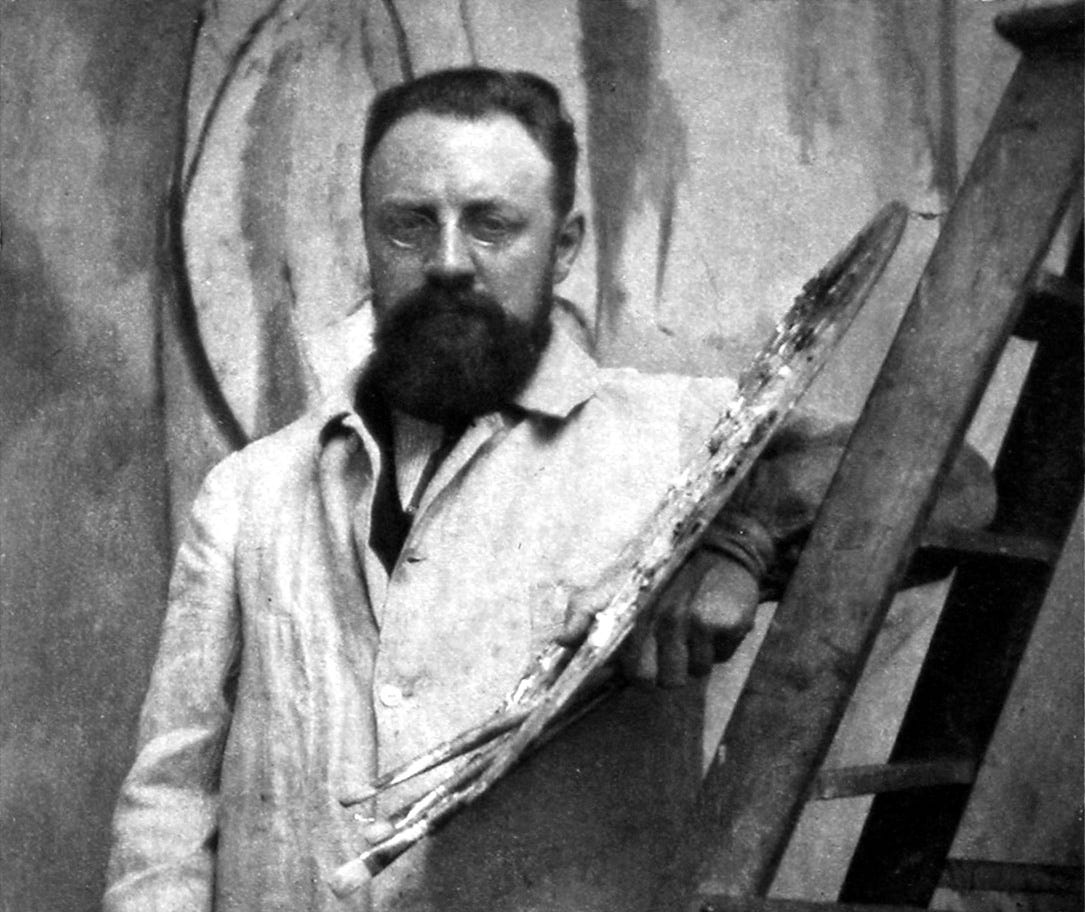

This arresting painting, made by the French Neoclassical artist Jacques-Louis David, does just that.

It shows a man lying collapsed in a bath, his head wrapped in a swathe of bandages, and a knife wound in his chest. In one hand he holds a letter, in the other a quill pen recently dipped in ink. In the bottom-left corner, you can see the bloodied implement of his murder…

It is a striking work of art: simple and silent. One of the great achievements of the work is that one can experience its drama directly before beginning to question what its story is.

With a theatrical boldness reminiscent of a scene plucked from a stage play, the painting exudes a cool, sober palette and employs a sparse, rectilinear composition to achieve its impact.

Look at the detail of the green blanket that covers the bath, which forms a horizontal rectangle that echoes the nocturnal shadows of the background. Also notice the upturned wooden box that acts as a makeshift table, this time a vertical block interrupting the green at right angles.

The geometrical patterns give the work a sense of strict order that has rarely been matched in the history of painting.

With this formal arrangement, you might go as far as to say that the image is beautiful, despite the subject matter. Soon enough, however, the elements of mystery give way to notions of strangeness: a dead man in a bath, a dignified but alarming scene, a blood-splattered letter in his hand.

The painting is based on the real-life murder of Jean-Paul Marat, a journalist and political radical during the French Revolution of the late 18th century.

Marat was a vocal defender of the lower classes and published his fervent views in pamphlets and newspapers, printing his own periodical L’Ami du Peuple (The Friend of the People) to circulate his opinions. In his personal life, he suffered from a severe skin condition which he eased by taking regular medicinal baths. Indeed, Marat was in a low state of health when he was killed, experiencing a heavy fever and an ongoing skin rash. He routinely wore bandages soaked in vinegar around his head to relieve the discomfort.

At a time of great social upheaval, which would ultimately lead to the overthrow of the French monarchy and the establishment of a republic, Marat won many admirers — not least the artist Jacques-Louis David — but also many rivals. One revolutionary faction, the Girondins, though in favour of removing the monarchy, were unhappy with the spiralling and bloodthirsty momentum of the Revolution.

Marat became one of their targets, especially for his leading role in the September Massacres when over a thousand imprisoned opponents of the Revolution were executed. And so, on the night of the 13th July 1793, Charlotte Corday, a sympathiser of the Girondins, entered Marat’s chambers with a kitchen knife and stabbed him once in the chest whilst he lay in his bath. She was quickly arrested and executed by guillotine four days later.

The artist David was asked to organise Marat’s funeral, which became the first opportunity to lionise the murdered revolutionary. A grand procession concluded at the Pantheon, with a cannon firing every five minutes.

Not long after, David was tasked with painting Marat’s portrait, which he did with the explicit intention of valorising Marat by turning his death into a political martyrdom. He had even visited Marat the day before the murder and reported that he found the revolutionary writing in his bath with “his last thoughts for the welfare of the people.” With the scene still etched in his memory, David decided to paint Marat in the position he’d last seen him.

The piece of paper in Marat’s hand is the letter that Corday used to gain admission into Marat’s private quarters, written to deceive the victim into welcoming his assassin. Translated into English, the letter reads:

“13. July, 1793

Marie anne Charlotte

Corday to the citizen

Marat

My great unhappiness

gives me a Right

to your kindness.”

David was the most prominent member of the Neoclassical movement. The emphasis of Neoclassicalism was on principles of simplicity and harmony, drawing inspiration from the culture of Greek and Roman antiquity. To evoke such antecedents was a rhetorical statement as much as it was about learning from the past: a representation of an event through noble and distinguished artistic principles.

Born in 1748, David’s painting style marked a turning point in the history of French art, away from the pleasure-seeking, game-playing traditions of Rococo and towards the more austere idealism of the classical world. His first decisive painting, the Oath of the Horatii (1784) was immediately recognized as a landmark in painting, and in its theme celebrated the virtues of the early Roman Republic.

David’s style was apt for the depiction of modern-day heroes, and every care has been taken to elevate his subject. In The Death of Marat, he employed a direct and uncompromising style, with a vantage point that is unflinchingly straight-on. It smooths over Marat’s infirmities, erasing any signs of skin disease. Instead, the victim is portrayed with a dignified, even devout poignancy.

David was known to have admired Caravaggio’s The Entombment of Christ, from which the gracefully hanging arm was a likely source of inspiration.

It suggests that David painted Marat with a deliberate attempt to evoke a Christ-like figure.

Moreover, at the very front of the image, beside the ink pot and quill, is a letter and banknote whose purpose is again to underscore Marat’s benevolence, since the letter reads simply “Give this banknote to the mother of five whose husband died defending the fatherland.”

There are no additional details, of the setting, time of day, or anything that tells us of the man’s status or background.

All we have is the semi-naked figure of a tragic martyr, adorned with the simple tribute from the artist engraved on the upturned box, ‘À MARAT, DAVID’. Below his dedication, David also dated the work as “Year Two”, the new calendar of the Revolution.

It is a potent and effective piece of propaganda.

The poet Baudelaire wrote of its effect in glowing terms, “The drama is here, vivid in its pitiful horror. This painting is David’s masterpiece and one of the great curiosities of modern art because, by a strange feat, it has nothing trivial or vile … This work contains something both poignant and tender; a soul is flying in the cold air of this room, on these cold walls, around this cold funerary tub.”

This article is an excerpt from my new book Great Paintings Uncovered, an exploration of some of art’s most compelling images.

Would you like to get…

A free guide to the Essential Styles in Western Art History, plus updates and exclusive news about me and my writing? Download for free here.

Join me…

On Instagram for more great paintings on the go!