In 1970s America, the initials MTM meant three things: actress Mary Tyler Moore; the show she starred in; and the company she and her husband Grant Tinker founded.

All three changed American life, but the third did so for decades, reinventing popular culture and turning the small screen into the dominant art form of its time.

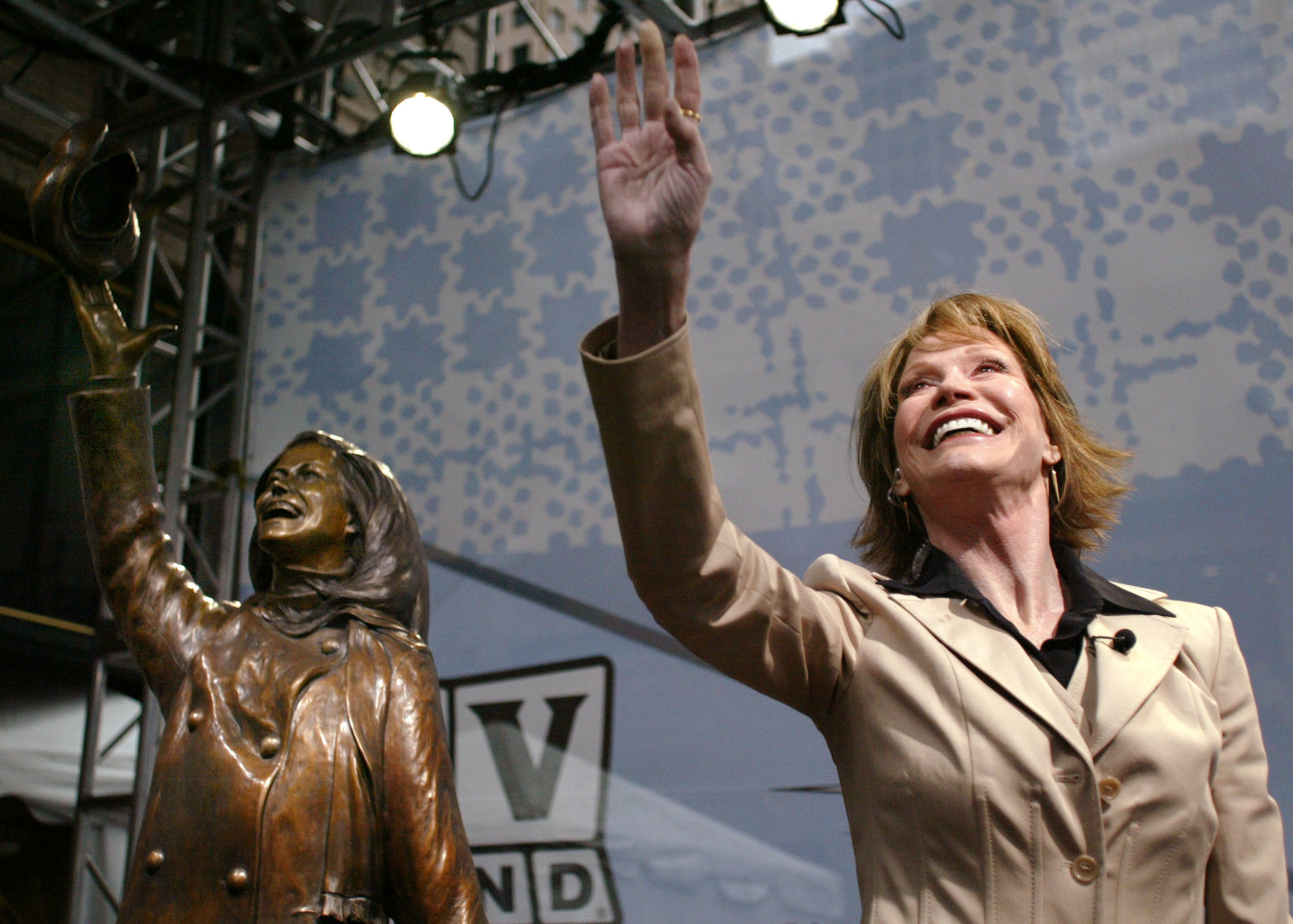

Mary Tyler Moore

In the 1950s, Lucille Ball and Jackie Gleason set the bar for TV comedy. In the 1960s, the bar was raised by The Dick Van Dyke Show. Carl Reiner and Dick Van Dyke created a more naturalistic comedy, in which gags were secondary to the humor of everyday life. As women’s roles evolved, Mary Tyler Moore became a national treasure: a sitcom wife who was beautiful, funny, and modern — the Jackie Kennedy of prime time.

As Van Dyke and Moore became the analog of the Kennedys, Moore found her own JFK on the set of the show. Grant Tinker was a handsome, polished, and charismatic ad executive, who married Moore before the show’s second season premiere.

The assassination of JFK took some of the sheen from television’s Camelot. In 1966, Reiner and Van Dyke ended the show at the top of their game. In 1969, Van Dyke invited Moore to appear on a reunion TV special, which became a massive hit. So CBS, searching for a young successor to Lucy, offered Moore a series of her own.

Moore and Tinker hesitated. Mary had just starred in one of the most beloved series of all time, and did not want to return a typical insipid sitcom. But Tinker had a thesis he wanted to test: Unlike other TV executives, he believed that television was fundamentally a writer’s medium. “From my earliest days around and about television,” he later wrote, “it’s been clear to me that good shows could only be made by good writers.”

On the back of this philosophy, Tinker and Moore created a new company to house their new show. It was called Mary Tyler Moore Enterprises, universally referred to as MTM.

They teamed up with young writing duo Allan Burns and James Brooks, and made a counter-proposal to CBS. They wanted full creative control of Moore’s new show, and an agreement that it would be produced by MTM. CBS agreed.

The Mary Tyler Moore Show

In 1970, two forces vied for the hearts of the networks. One was their desire to play it safe, to avoid controversy, to stick to selling soap. The other was a desire to capture new audiences—in this case, the ascendant ’60s generation that wanted to see TV characters that they could relate to.

It was inevitable that these forces would go to war. The battleground turned out to be The Mary Tyler Moore Show.

As Norman Lear would do that same year, Tinker and Moore decided to create a new show for a new decade. They left it to Brooks and Burns to work out the details. The two young producers came back to the things they knew: since Mary couldn’t play another housewife, they decided that the show should be a workplace comedy. Since Dick Van Dyke had proven that TV itself worked as a setting, they decided to put Mary’s character into the world they all knew best.

They found their high concept: Mary Richards would work in a TV newsroom. And unlike every other leading lady on TV, Mary’s character would be divorced. They pitched the idea to Moore and Tinker, who both loved it: in 1970, divorce on TV was the definition of new.

CBS executive Mike Dann was horrified, and brought in the head of CBS research, who summarized the brilliance of 1970 network television:

“Our research says American audiences won’t tolerate divorce in a lead of a series any more than they will tolerate Jews, people with moustaches, and people who live in New York.”

So MTM eliminated the divorce, and fleshed out the characters with whom Mary would work. Rehearsals began in an old Desilu lot, the same one where I Love Lucy had been shot.

CBS hated the show. Executive Mike Dann offered to buy MTM out: take the money and walk away, he advised Tinker. Don’t throw good money after bad. Tinker and Moore refused. They had a thirteen-episode contract and would hold CBS to it.

So Dann put The Mary Tyler Moore Show somewhere no one would ever see it. He scheduled it on Tuesday nights between The Beverly Hillbillies and Hee Haw. It was the perfect timeslot to be seen by a rural audience that would hate it.

CBS owner William Paley would soon do the same thing with a show he hated, called All In The Family. In both cases, CBS buried their future saviors, and waited for them to die.

But Mike Dann was soon out at CBS, and new executives rescued both shows from the graveyard. They put them on Saturday night in prime time: All in the Family at 8 PM and The Mary Tyler Moore Show at 9 PM. Both shows struggled to find an audience, until the 1971 Emmy Awards — at which The Mary Tyler Moore Show garnered four wins and eight nominations. Soon more than 20 million people were watching Mary; by 1974, viewership grew to 43 million, a number utterly impossible today.

The Wall Street Journal called Mary “the best show on television, week in and week out… [viewers] are watching people much like themselves—doomed to live imperfect lives, often comically mixed-up lives, still stretching for a measure of dignity.”

With these two shows, plus M*A*S*H, The Bob Newhart Show and The Carol Burnett Show, CBS created the greatest and most successful lineup that television has ever seen. In the years that this lineup aired, nearly fifty million Americans stayed home on Saturday night— half the TV homes in America, watching the same five shows, at the same time.

It was the TV equivalent of the 1927 Yankees, and it would never happen again.

As Mary continued and MTM grew, Brooks and Burns sought out women writers, making The Mary Tyler Moore Show the first TV production that was shaped and written by women. By 1973, twenty-five of the seventy-five writers on Mary were female. As MTM addressed issues including equal pay, divorce, infidelity, and prostitution, millions of women saw Mary Richards as the only authentic woman on TV.

Mary cemented its status as the most sophisticated show on television. First Lady Betty Ford made an appearance, as did Walter Cronkite, playing himself. So did Johnny Carson, the most powerful man in television, who never appeared on any show but his own.

Mary could not get any bigger, but the world around it was changing again. Like Reiner and Van Dyke before them, Moore and Tinker decided to end at the top of their game. In the final episode, in 1977, Moore gave her final speech:

I just wanted you to know that sometimes I get concerned about being a career woman. I get to thinking my job is too important to me, and I tell myself that the people I work with are just the people I work with, and not my family. And last night, I thought, “What is a family, anyway?” They’re just people who make you feel less alone and really loved. And that’s what you’ve done for me. Thank you for being my family.

Millions of viewers felt the same way about her.

MTM

By that time, MTM was an industry force, grossing more than $20 million, with eight comedies in production. Fueled by Tinker’s elevation of the writer, it became the place everyone in television wanted to work. Writer Gary David Goldberg summed up prevailing sentiment, calling MTM “Camelot for writers.” “Grant makes everyone he comes in contact with better,” he said later. MTM soon went from reinventing comedy to revolutionizing drama, beginning with seminal NBC hit Hill Street Blues.

Of the Emmy awards for best comedy and best drama from 1971-1994, 50 percent went to shows produced by MTM or its alumni. MTM former staffers dominated the next twenty years of television on shows including Cagney and Lacey, Cheers, Chicago Hope, Cosby, ER, Family Ties, Frazier, Friends, The Golden Girls, Miami Vice, NYPD Blue, Saturday Night Live, The Simpsons and Two and a Half Men.

Mary co-creator James L. Brooks went on to create cult comedy Taxi. When it was canceled, he transitioned to film, where he produced, directed, and wrote Oscar winner Terms of Endearment and Broadcast News. In 1987, he returned to TV on the struggling fourth network, ordering some cartoons from illustrator Matt Groening. FOX spun them into their own show, which Brooks co-produced. It eventually became the longest-running comedy of all time—The Simpsons.

In syndication, The Mary Tyler Moore Show inspired of a new generation of performers and writers. Oprah Winfrey said the show was “a light in my life, and Mary was a trailblazer for my generation. She’s the reason I wanted my own production company.” When Moore gave Oprah a version of Mary’s iconic wooden “M”— a golden “O” — Winfrey became speechless, then burst into tears.

Moore was the most significant actress of her era. The woman who refused Gloria Steinem’s invitation to join the feminist movement broke down more barriers for women artists and characters than any other American of her time. When asked how she wanted to be remembered, she said: “As somebody who always looked for the truth, even if it wasn’t funny.”

In 1998, Entertainment Weekly named The Mary Tyler Moore Show the best TV show of all time.

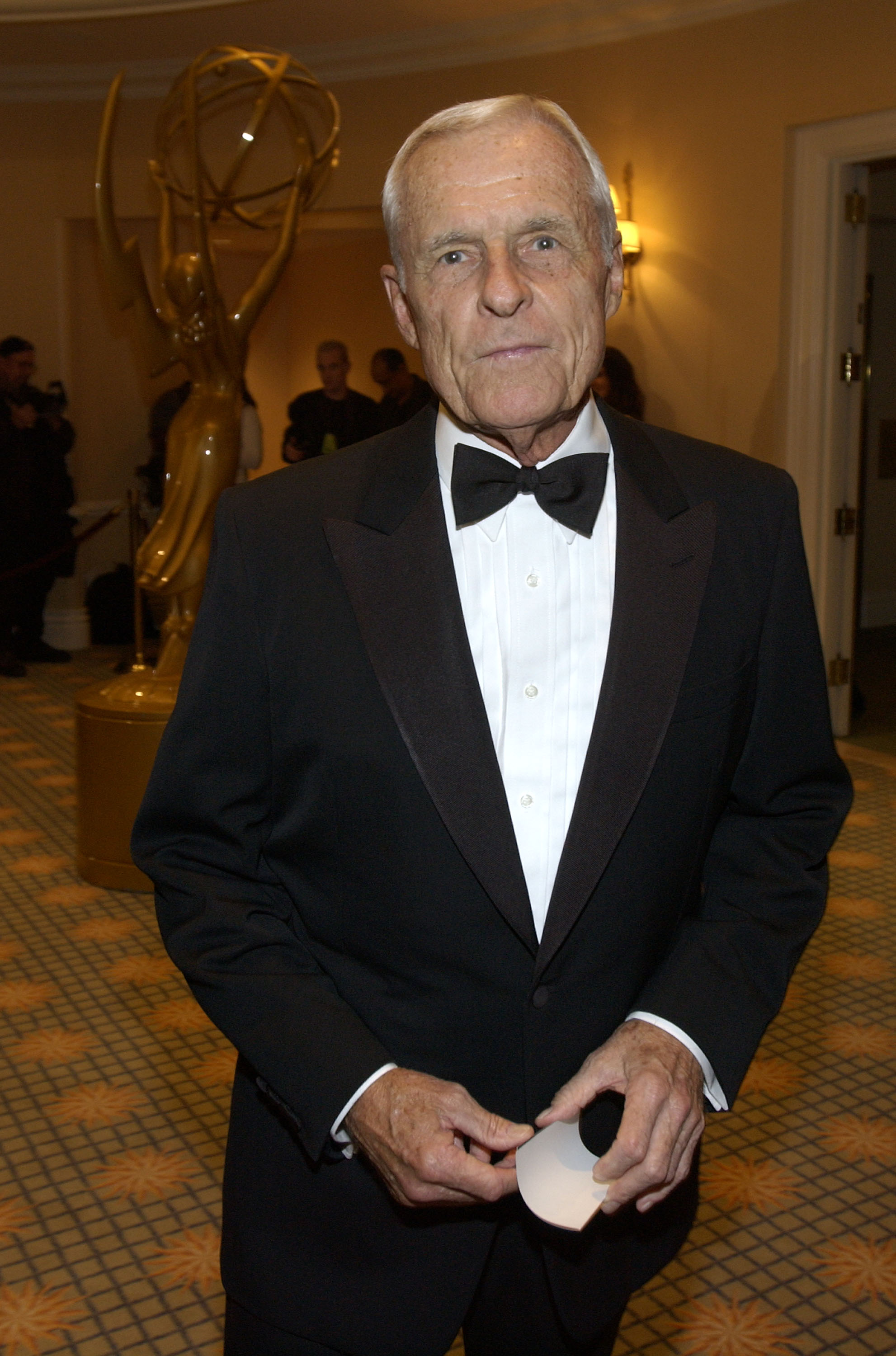

Grant Tinker went on to run NBC three separate times, eventually taking the network from #3 to #1. He is venerated by those who worked with him, especially the many writers whose careers he advanced control. When protégé Steven Bochco was offered the chance to run a network, Tinker’s response was characteristic: “Are you crazy? You have a typewriter. Why the hell would you ever want to run a network when you can write?”

According to author Brett Martin, a veteran TV writer “once sketched a family history of quality TV. After starting at the bottom with The Sopranos, The Wire, and Mad Men… he quickly moved upward, along a spreading spiderweb of connections… At the top, alone, he wrote one name in capital letters: Grant Tinker.”

Grant Tinker died on November 30, 2016 at aged 90. His ex-wife and former muse passed away a few weeks later, on January 25, 2017. Together, they raised the standard for the stories of our times. Viva MTM.

Two-time Emmy® Award winner Seth Shapiro is a leading consultant in innovation, media and technology. His first book, Television: Innovation, Disruption, and the World’s Most Powerful Medium, was published in July He teaches at The USC School of Cinematic Arts, is a Governor at The Television Academy, and can be reached at info@sethshapiro.com. His previous pieces for The Observer are here.