Photo: Stanley Bielecki/ASP/Getty Images

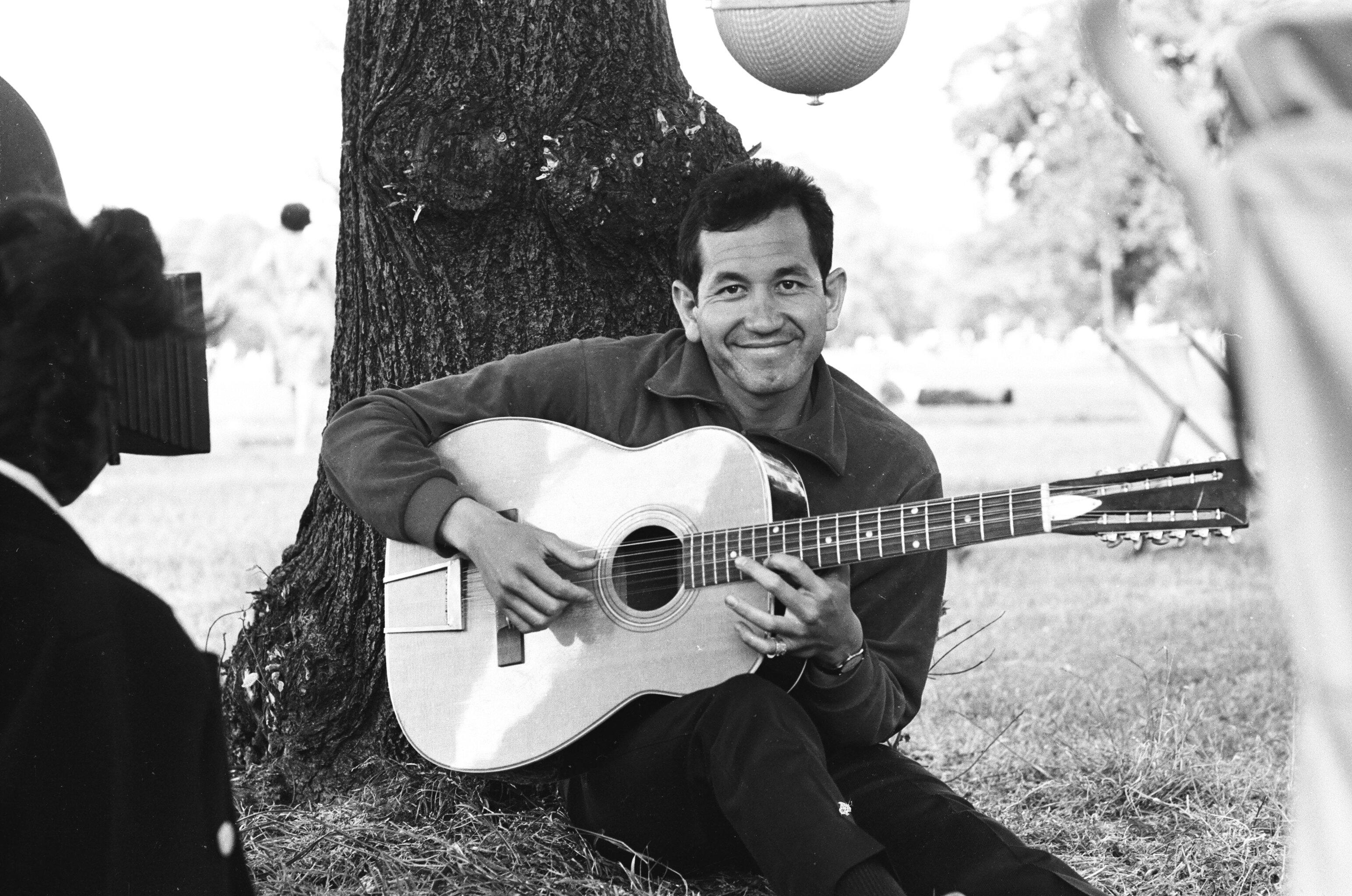

Trini Lopez in London in 1965

news

Trini Lopez, Who Revitalized American & Mexican Folk Classics, Has Died From COVID-19 At 83

The GRAMMY-nominated singer/guitarist's biggest global hits were lively covers of folk trio Peter, Paul and Mary's "If I Had a Hammer" and "Lemon Tree"

GRAMMY-nominated singer, guitarist and actor Trini Lopez, whose lively blend of American and Mexican folk songs with rockabilly flair earned him worldwide fame in the '60s, has died at 83. The Mexican-American artist died from COVID-19 at a hospital in Rancho Mirage, Calif. yesterday, Aug. 11.

Beginning with his 1963 debut studio album, Trini Lopez At PJ's, Lopez found success bringing new life—and a raucous, danceable beat and vocal delivery—to other artists' songs, including folk trio Peter, Paul and Mary's hits "If I Had a Hammer" and "Lemon Tree." Both songs would be his biggest, with his versions out-charting theirs both on the Billboard Hot 100 and international charts.

Back at the 6th GRAMMY Awards in 1964, following his epic breakout year, Lopez was nominated for Best New Artist.

If I Had A Hammer: From Aretha Franklin To Public Enemy, Here's How Artists Have Amplified Social Justice Movements Through Music

His rocked-up rendition of "I Had a Hammer," released in 1963 on his live debut album, hit No. 3 on the Hot 100 and No. 1 in 36 countries. The song was originally written by political activist/folk icon Pete Seeger and Lee Hays and recorded as a protest song by their band The Weavers in 1950, reemerging as a GRAMMY-winning No. 10 hit from Peter, Paul and Mary in 1962, the year prior to Lopez's breakout success with the classic song.

Popular '60s West Hollywood star-studded venue P.J.'s, where the Dallas-born singer recorded his first two albums (which also put the club on the map outside of Los Angeles), was where he got his big break, from none other than Frank Sinatra. After catching a few of his shows, the Rat Pack leader signed him to his Reprise label.

"I remember reading in the trades that Frank Sinatra frequented P.J.’s a lot so I moved over there so I could meet him," Lopez said. "I was hired for three weeks and I stayed a year and a half. I played four or five shows every single night and I never repeated a song. I just kept waiting to meet Frank Sinatra, and within a month he came with an entourage and to my surprise he offered me an eight-year record contract on his label. I put P.J.'s on the map with my live albums since they were recorded for Sinatra's record company."

Read: Sin-atra City: The story of Frank Sinatra and Las Vegas

A self-proclaimed "proud" Mexican-American born to immigrant parents in Dallas in 1937, Lopez also performed and recorded many songs in Spanish at a time when artists, including himself, were asked by labels to hide or Whitewash their Latin identity. Trini Lopez At PJ's included a rendition of traditional Mexican folk song "Cielito Lindo" and in 1964, he released The Latin Album, filled with of Spanish language classics. His father, Trinidad Lopez II, was a ranchera singer who made his living as manual laborer.

As The Guardian notes, "in the mid-'60s he was releasing as many as five albums a year, though that slowed in the late '70s. While he continued performing, he released very little music until 2000, when he began recording again and released a further six albums." His final album, released in 2011 and titled Into the Future, was a nod to Sinatra, featuring songs from his catalog.

Save Our Venues: Capturing Los Angeles' COVID-Closed Venues

At the peak of his musical fame in the '60s and '70s, he also found moderate success in film and TV, with roles in films The Dirty Dozen (1967) and Antonio (1973) and a variety show special on NBC in 1969, "The Trini Lopez Show."

A talented guitar player—he started playing at age 11—Gibson Guitars had him design two instruments in 1964, which remain highly sought after to this day. Dave Grohl and Noel Gallagher are both fans of the vintage models. Grohl paid tribute to Lopez on Twitter today, underscoring that he's used his on every Foo Fighters album ever recorded.

His electric live performances and hit records made him an in-demand artist in the Las Vegas circuit, as well as around the globe, including one jaunt he found most memorable—stealing the show as the Beatles' opener in Paris in 1964.

"I used to steal the show from them every night!" he said in a 2014 interview. "The French newspapers would say, 'Bravo, Trini Lopez! Who are the Beatles?'"

interview

Slash's New Blues Ball: How His Collaborations Album 'Orgy Of The Damned' Came Together

On his new album, 'Orgy Of The Damned,' Slash recruits several friends — from Aerosmith's Steven Tyler to Demi Lovato — to jam on blues classics. The rock legend details how the project was "an accumulation of stuff I've learned over the years."

In the pantheon of rock guitar gods, Slash ranks high on the list of legends. Many fans have passionately discussed his work — but if you ask him how he views his evolution over the last four decades, he doesn't offer a detailed analysis.

"As a person, I live very much in the moment, not too far in the past and not very far in the future either," Slash asserts. "So it's hard for me to really look at everything I'm doing in the bigger scheme of things."

While his latest endeavor — his new studio album, Orgy Of The Damned — may seem different to many who know him as the shredding guitarist in Guns N' Roses, Slash's Snakepit, Velvet Revolver, and his four albums with Myles Kennedy and the Conspirators, it's a prime example of his living-in-the-moment ethos. And, perhaps most importantly to Slash, it goes back to what has always been at the heart of his playing: the blues.

Orgy Of The Damned strips back much of the heavier side of his playing for a 12-track homage to the songs and artists that have long inspired him. And he recruited several of his rock cohorts — the likes of AC/DC's Brian Johnson, Aerosmith's Steven Tyler, Gary Clark Jr., Iggy Pop, Beth Hart, and Dorothy, among others — to jam on vintage blues tunes with him, from "Hoochie Coochie Man" to "Born Under A Bad Sign."

But don't be skeptical of his current venture — there's plenty of fire in these interpretations; they just have a different energy than his harder rocking material. The album also includes one new Slash original, the majestic instrumental "Metal Chestnut," a nice showcase for his tastefully melodic and expressive playing.

The initial seed for the project was planted with the guitarist's late '90s group Slash's Blues Ball, which jammed on genre classics. Those live, spontaneous collaborations appealed to him, so when he had a small open window to get something done recently, he jumped at the chance to finally make a full-on blues album.

Released May 17, Orgy Of The Damned serves as an authentic bridge from his musical roots to his many hard rock endeavors. It also sees a full-circle moment: two Blues Ball bandmates, bassist Johnny Griparic and keyboardist Teddy Andreadis, helped lay down the basic tracks. Further seizing on his blues exploration, Slash will be headlining his own touring blues festival called S.E.R.P.E.N.T. in July and August, with support acts including the Warren Haynes Band, Keb' Mo', ZZ Ward, and Eric Gales.

Part of what has kept Slash's career so intriguing is the diversity he embraces. While many heavy rockers stay in their lane, Slash has always traveled down other roads. And though most of his Orgy Of The Damned guests are more in his world, he's collaborated with the likes of Michael Jackson, Carole King and Ray Charles — further proof that he's one of rock's genre-bending greats.

Below, Slash discusses some of the most memorable collabs from Orgy Of The Damned, as well as from his wide-spanning career.

I was just listening to "Living For The City," which is my favorite track on the album.

Wow, that's awesome. That was the track that I knew was going to be the most left of center for the average person, but that was my favorite song when [Stevie Wonder's 1973 album] Innervisions came out when I was, like, 9 years old. I loved that song. This record's origins go back to a blues band that I put together back in the '90s.

Slash's Blues Ball.

Right. We used to play "Superstition," that Stevie Wonder song. I did not want to record that [for Orgy Of The Damned], but I still wanted to do a Stevie Wonder song. So it gave me the opportunity to do "Living For The City," which is probably the most complicated of all the songs to learn. I thought we did a pretty good job, and Tash [Neal] sang it great. I'm glad you dig it because you're probably the first person that's actually singled that song out.

With the Blues Ball, you performed Hoyt Axton's "The Pusher" and Robert Johnson's "Crossroads," and they surface here. Isn't it amazing it took this long to record a collection like this?

[Blues Ball] was a fun thrown-together thing that we did when I [was in, I] guess you call it, a transitional period. I'd left Guns N' Roses [in 1996], and it was right before I put together a second incarnation of Snakepit.

I'd been doing a lot of jamming with a lot of blues guys. I'd known Teddy [Andreadis] for a while and been jamming with him at The Baked Potato for years prior to this. So during this period, I got together with Ted and Johnny [Griparic], and we started with this Blues Ball thing. We started touring around the country with it, and then even made it to Europe. It was just fun.

Then Snakepit happened, and then Velvet Revolver. These were more or less serious bands that I was involved in. Blues Ball was really just for the fun of it, so it didn't really take precedence. But all these years later, I was on tour with Guns N' Roses, and we had a three-week break or whatever it was. I thought, I want to make that f—ing record now.

It had been stewing in the back of my mind subconsciously. So I called Teddy and Johnny, and I said, Hey, let's go in the studio and just put together a set and go and record it. We got an old set list from 1998, picked some songs from an app, picked some other songs that I've always wanted to do that I haven't gotten a chance to do.

Then I had the idea of getting Tash Neal involved, because this guy is just an amazing singer/guitar player that I had worked with in a blues thing a couple years prior to that. So we had the nucleus of this band.

Then I thought, Let's bring in a bunch of guest singers to do this. I don't want to try to do a traditional blues record, because I think that's going to just sound corny. So I definitely wanted this to be more eclectic than that, and more of, like, Slash's take on these certain songs, as opposed to it being, like, "blues." It was very off-the-cuff and very loose.

It's refreshing to hear Brian Johnson singing in his lower register on "Killing Floor" like he did in the '70s with Geordie, before he got into AC/DC. Were you expecting him to sound like that?

You know, I didn't know what he was gonna sing it like. He was so enthusiastic about doing a Howlin' Wolf cover.

I think he was one of the first calls that I made, and it was really encouraging the way that he reacted to the idea of the song. So I went to a studio in Florida. We'd already recorded all the music, and he just fell into it in that register.

I think he was more or less trying to keep it in the same feel and in the same sort of tone as the original, which was great. I always say this — because it happened for like two seconds, he sang a bit in the upper register — but it definitely sounded like AC/DC doing a cover of Howlin' Wolf. We're not AC/DC, but he felt more comfortable doing it in the register that Howlin' Wolf did. I just thought it sounded really great.

You chose to have Demi Lovato sing "Papa Was A Rolling Stone." Why did you pick her?

We used to do "Papa Was A Rolling Stone" back in Snakepit, actually, and Johnny played bass. We had this guy named Rod Jackson, who was the singer, and he was incredible. He did a great f—ing interpretation of the Temptations singing it.

When it came to doing it for this record, I wanted to have something different, and the idea of having a young girl's voice telling the story of talking to her mom to find out about her infamous late father, just made sense to me. And Demi was the first person that I thought of. She's got such a great, soulful voice, but it's also got a certain kind of youth to it.

When I told her about it, she reacted like Brian did: "Wow, I would love to do that." There's some deeper meaning about the song to her and her personal life or her experience. We went to the studio, and she just belted it out. It was a lot of fun to do it with her, with that kind of zeal.

You collaborate with Chris Stapleton on Fleetwood Mac's "Oh Well" by Peter Green. I'm assuming the original version of that song inspired "Double Talkin' Jive" by GN'R?

It did not, but now that you mention it, because of the classical interlude thing at the end... Is that what you're talking about? I never thought about it.

I mean the overall vibe of the song.

"Oh Well" was a song that I didn't hear until I was about 12 years old. It was on KMET, a local radio station in LA. I didn't even know there was a Fleetwood Mac before Stevie Nicks and Lindsey Buckingham. I always loved that song, and I think it probably had a big influence on me without me even really realizing it. So no, it didn't have a direct influence on "Double Talkin' Jive," but I get it now that you bring it up.

Was there something new that you learned in making this album? Were your collaborators surprised by their own performances?

I think Gary Clark is just this really f—ing wonderful guitar player. When I got "Crossroads," the idea originally was "Crossroads Blues," which is the original Robert Johnson version. And I called Gary and said, "Would you want to play with me on this thing?"

He and I only just met, so I didn't know what his response was going to be. But apparently, he was a big Guns N' Roses fan — I get the idea, anyway. We changed it to the Cream version just because I needed to have something that was a little bit more upbeat. So when we got together and played, we solo-ed it off each other.

When I listen back to it, his playing is just so f—ing smooth, natural, and tasty. There was a lot of that going on throughout the making of the whole record — acclimating to the song and to the feel of it, just in the moment.

I think that's all an accumulation of stuff that I've learned over the years. The record probably would be way different if I did it 20 years ago, so I don't know what that evolution is. But it does exist. The growth thing — God help us if you don't have it.

You've collaborated with a lot of people over the years — Michael Jackson, Carole King, Lemmy, B.B. King, Fergie. Were there any particular moments that were daunting or really challenging? And was there any collaboration that produced something you didn't expect?

All those are a great example of the growth thing, because that's how you really grow as a musician. Learning how to adapt to playing with other people, and playing with people who are better than you — that really helps you blossom as a player.

Playing with Carole King [in 1993] was a really educational experience because she taught me a lot about something that I thought that I did naturally, but she helped me to fine tune it, which was soloing within the context of the song. [It was] really just a couple of words that she said to me during this take that stuck with me. I can't remember exactly what they were, but it was something having to do with making room for the vocal. It was really in passing, but it was important knowledge.

The session that really was the hardest one that I ever did was [when] I was working with Ray Charles before he passed away. I played on his "God Bless America [Again]" record [on 2002's Ray Charles Sings for America], just doing my thing. It was no big deal. But he asked me to play some standards for the biopic on him [2004's Ray], and he thought that I could just sit in with his band playing all these Ray Charles standards.

That was something that they gave me the chord charts for, and it was over my head. It was all these chord changes. I wasn't familiar with the music, and most of it was either a jazz or bebop kind of a thing, and it wasn't my natural feel.

I remember taking the chord charts home, those kinds you get in a f—ing songbook. They're all kinds of versions of chords that wouldn't be the version that you would play.

That was one of those really tough sessions that I really learned when I got in over my head with something. But a lot of the other ones I fall into more naturally because I have a feel for it.

That's how those marriages happen in the first place — you have this common interest of a song, so you just feel comfortable doing it because it's in your wheelhouse, even though it's a different kind of music than what everybody's familiar with you doing. You find that you can play and be yourself in a lot of different styles. Some are a little bit challenging, but it's fun.

Are there any people you'd like to collaborate with? Or any styles of music you'd like to explore?

When you say styles, I don't really have a wish list for that. Things just happen. I was just working with this composer, Bear McCreary. We did a song on this epic record that's basically a soundtrack for this whole graphic novel thing, and the compositions are very intense. He's very particular about feel, and about the way each one of these parts has to be played, and so on. That was a little bit challenging. We're going to go do it live at some point coming up.

There's people that I would love to play with, but it's really not like that. It's just whatever opportunities present themselves. It's not like there's a lot of forethought as to who you get to play with, or seeking people out. Except for when you're doing a record where you have people come in and sing on your record, and you have to call them up and beg and plead — "Will you come and do this?"

But I always say Stevie Wonder. I think everybody would like to play with Stevie Wonder at some point.

Incubus On Revisiting Morning View & Finding Rejuvenation By Looking To The Past

Photo: Eric Rojas

interview

Grupo Frontera On 'Jugando A Que No Pasa Nada' & Fully Expressing Themselves: "This Album Was Made From The Heart"

With their second album, regional Mexican music stars Grupo Frontera aim to honor their roots while showing their wide-spanning musical interests. Hear from some of the group on the creation of the album and why it's so special to them.

In just two years, Grupo Frontera have gone from playing weddings in their native Texas to joining Bad Bunny on stage at Coachella and performing on "The Tonight Show Starring Jimmy Fallon." No matter how rapid their rise to fame has become, the Texas sextet has held the same ethos: celebrating their Mexican heritage while embracing the American culture they were born into.

Embracing that balance has helped them transcend cultural barriers with their modern take on regional Mexican music, which incorporates a wide range of musical styles. That holds true on Grupo Frontera's second album, Jugando A Que No Pasa Nada, out now.

With bright accordion lines and a high-energy blend of urbano party anthems, cumbia-inspired ballads, and forays into pop, the album is a masterful display of the group's mixed cultural background. It retains the same Latin cowboy spirit of their first LP, 2023's El Comienzo — which had roots in the norteño genre, a traditional style originated in Northern Mexico — while tapping into the music they grew up listening to in the States, like hip-hop, corridos tumbados, and country music.

While El Comienzo introduced Grupo Frontera as loyal traditionalists, Jugando A Que No Pasa Nada aims at speaking to younger generations. It's a fitting approach for the group, whose ages range from early twenties to early thirties across its six members — Alberto "Beto" Acosta, Juan Javier Cantú, Carlos Guerrero, Julian Peña Jr., Adelaido "Payo" Solis III, and Carlos Zamora — that also speaks to their evolution amid their whirlwind success. It's proof that they aren't afraid to create music that is completely true to them — and that's exactly what makes Jugando A Que No Pasa Nada special.

Below, Cantu, Guerrero, Peña, and Solis speak with GRAMMY.com about their cultural roots in South Texas and the making of Jugando A Que No Pasa Nada.

The last two years were a very prolific time for Grupo Frontera. What was it like to create Jugando A Que No Pasa Nada after everything that's happened to the group?

Adelaido "Payo" Solis: Last year we were working a lot, playing four or five concerts a week, and that didn't give us time to structure El Comienzo as well as we wanted to. Now we made time to record all these different types of songs. It was amazing to have time to work on the album cover and all the songs the way we wanted to, and have everything set in a certain way to represent the new album to its highest potential.

Between 2023 and this year, were you able to take any time off to work on this new record, or was it done in between touring?

Juan Javier Cantú: There were times when we were touring El Comienzo that we would record before the people got inside the theater. We would record onstage. We'd be like "Wait, don't let the people in — 20 more minutes, we have to finish this session!" That happened with our new songs "Quédate Bebé" and "Nunca La Olvidé."

Solis: It's a little bit of both because those were recorded live, but then two months ago, we locked ourselves in the house for a good four or five days, and out of that came, like, 15 more songs.

You mentioned that, for this new record, you had more time to work on the order of the songs. What's the general feeling behind this track list? Starting with "F—ing Amor."

Solis: The general feel of this album is literally the album's name, Jugando A Que No Pasa Nada [which loosely translates to "pretending everything is OK"]. Since we had more time to think about it, we tied many things to that name, to that phrase.

Everyone, at some point, has pretended everything is OK when in reality, it's not. You can see it in the album cover — the truck is on fire, but our character, who represents Grupo Frontera, is sitting in the car as if nothing is wrong. So the idea — and I know everyone experienced this — is that when you get in your truck, you can play our record and you can drop the act. You can stop pretending everything is alright. You can get in your feelings.

So the way it's structured, starting with "F—king Amor," is that you don't want to know anything about love, then in the middle, you have "Ya Pedo Quién Sabe," which says "maybe I miss you," and then by the end, "Quédate Bebe" [which translates to "Stay Baby"]. So it is a ride, an experience, which starts with you being hurt, or left behind by someone, and you being sad about it, then slowly wondering how is she doing, then saying "I miss you," and finally "stay with me."

Cantú: More than anything, we are playing with genres. In this record, you have our traditional cumbias, country music, and then songs like "Desquite." So that was also the goal, for people to know more about our music and the music we like.

Solis: Each member of Grupo Frontera listens and plays different styles, so starting from that, we each had a big say in the genres we wanted to play and styles we wanted to record on this album.

More than anything, we were thinking of new generations. The Latinos of newer generations that don't speak Spanish, or don't get to come back often to Mexico or the countries where their parents are from. They don't want to hear just cumbia, so in our album, we want to make all these styles for them to find, in our songs, the genres that they like.

You mentioned that each of you has different styles and genres you brought to the new record. How did you work in the studio to generate these new sounds?

Solis: Grupo Frontera doesn't really use a lot of computer sounds, most of the music we play is through our instruments. We used to work on our songs starting from guitar and voice only, but now because we had more time to work on things, we each took a song and would listen to it for days. Then we'd meet again as a group and work on it in the studio: everyone's opinion counts, and no one's opinion takes precedence over the other. That's how, slowly, each new song took shape.

When you talked about the moment in which you get in your car or truck, and finally get to stop pretending everything is alright — does that car culture come from your upbringing in Texas?

Julián Peña: That culture is definitely from where we are from, from the Valley [the Lower Rio Grande Valley, which spans the border of Texas and Mexico], where there are a lot of troquitas tumbadas [lowered or customized pickup trucks]. You'd hear la Raza zooming by, blasting our songs, with the bass booming, from their trucks. So it's kind of like a relief, your safe space.

Like the album's title says, "pretending everything is fine"... you're pretending to be fine and then once you get in your car and you pass yourself the aux, you turn that up and you start bawling, or feeling whatever you're feeling. Then the album's over, gotta get back to work, clock back in, and go back to pretending everything's fine. It's like an escape that we know many people have, it has happened to all of us; you go on a drive to decompress, turn the music up, let it all out, and feel better. That's what we wanted to capture with that image.

What songs did you each play when you needed that kind of moment?

Cantú: When I broke up with a girlfriend, around 2012, my go-to was Drake.

Peña: Mine was "Then," by Brad Paisley. I was just sad and going through a country phase. [Laughs.]

Solis: I would listen a lot to a song by Eslabón Armado called "Atrapado."

Cantú: When I feel a little trapped by this street lifestyle I go, "I Should've Been A Cowboy"! [All laugh.]

I read some of you grew up raising cattle, or come from families of farmers and ranchers. What aspects of that lifestyle do you miss, in contrast with being in a city like LA, and actively involved in the music industry?

Solis: Juan had his ranch around General Bravo [a municipality in Mexico], and I was born in the States, but I would go every weekend to Mexico, to my parent's ranch, where they had cattle. I know Juan can relate to this — when you are at the ranch and play a song, and can sing out loud without anyone around listening or judging you, that's a really nice feeling. When you are on stage, in the industry, you're not singing only to yourself, but to make the audience's day better. So no matter what you're going through, when you're on stage, your job is to make people happy.

Cantú: Going to a place — like a ranch, an open space — to disconnect, it's like a reset. I feel a lot of people have not experienced that, they don't know the power that has.

Through your lyrics, you adapted old love songs and romance to modern times. Some songs even mention emojis, DMs and texting. Do you have any favorite emojis?

Solis: Oh man, I love the black heart emoji because it can mean many things. A dead heart, or that you're not feeling anything. It can mean your heart is broken and needs mending to go back to being red. I think it's super cool.

Carlos Guerrero: I like the thinking face emoji.

Cantú: Sometimes he uses it out of context and we don't know if he's thinking, or he's mad. [Laughs.] For me, the one I use the most is the "thanks" [praying hands emoji].

Peña: I like the heart hands emoji. Like "Hey what's up," and throw a heart hands emoji.

Going back to your music, what's your favorite part of making songs?

Solis: I'm not sure if we all have the same answer, but for me, my favorite part about being able to sing, record and write these songs is to sing them with all the feeling in the world. And that is amazing, to be able to let that out.

Cantú: The simple fact of creating something and getting to test it out, seeing people sing it, it's like, Wow, we made that.

Peña: Yeah, that you do something and then put that out there right and you're like, I wonder if this feeling is gonna get translated the way we want it to. And then, like Juan said, when people go to concerts, and sing it back to us, or we see people post stories of them singing it and going through it. It's like, we made that! We got that point across, and it feels good for all of us.

How do you navigate being an American band with a cross-cultural upbringing?

Cantú: It's really cool. We were lucky to go to Puerto Rico, Colombia and Argentina, to collaborate with artists like Arcángel, Maluma, Shakira, and Nicki Nicole. That helped us understand their culture and meditate on what it means to be Latino, not just Mexican. Latino identity entails so many cultures in one, and even Mexican identity is vast. Latinos are from everywhere.

How was it to collaborate with all these other artists, and open your group to collaborate with them in Jugando A Que No Pasa Nada?

Solis: Basically, we are like a group of brothers. We sometimes spend 24/7 together. We see each other every day, and we spend all our time together on the tour bus and at home, even when we don't need to see each other. So when we collaborate with other artists, like Morat, Maluma, or Nicky Nicole, they sense that vibe — we carry that with us. I feel that carries through, to the point where we can all have that vibe together.

When we are collaborating with other artists, it feels as if it was a friendship that has been around for a while. Like, have you ever felt or had that friendship where you can go like a month without seeing each other and when you see each other is like you had seen each other? That's basically how it is when we collab with other artists.

I know it's hard to pick a favorite song from the new album—

Solis: It's not that hard! My favorite is "F—ing Amor."

Why?

Solis: Because before Grupo Frontera started, that was more the style that I listened to. I got into the music of Natanael Cano, Iván Cornejo, and others. I grew up listening to old cumbia songs that my parents played for me, but in high school, I started listening to new stuff and new genres, so I think that's why my musical style is more versatile. So "F—ing Amor" is more Sierreño, has more bass, and the congas and percussion; the vibe of that song reminds me of how, in high school, I would drive my truck listening to Natanael Cano.

Peña: Mine is "Echándote De Menos." Ever since we recorded it, it has that rhythm in the middle where we all drop, on that note… I like all of them, but that one, in particular.

Cantú: I have to go with two. When I first listened to them, "Los Dos," our collaboration with Morat, and "Por Qué Será" with Maluma. That song, when they first showed it to me, I felt chills down my back.

Guerrero: Mine is "Los Dos," with Morat, because we liked Morat before being with Frontera.

Cantú: To make a song with them is an achievement for us because our big song ["No Se Va"] was a cover of theirs. So making a song together is pretty cool — not many people get to do that.

Solis: We had people tell us that we were stealing their song! We get that Morat is some people's favorite group but we were like, bro, it is our favorite too, that's why we did that song!

What is your dream for this new record?

Solis: We were talking about this yesterday in the van. We don't want to expect anything out of it — success, or big numbers — because this album was made from the heart. We are just so happy and proud to be releasing it into the world.

Guerrero: I just hope that people like it, because, as Payo says, we explored a lot of different genres, so we hope people dig that. We put our best into it.

Cantú: I want what Payo and Carlos said, but also, to go to Japan to play our songs.

Peña: I want what the three of them want, but for people to really connect and identify with the songs. Even if they connect with one or three, what I want for the album is that — to connect with people.

Meet The Gen Z Women Claiming Space In The Regional Mexican Music Movement

Photo: Timothy Norris/Getty Images

list

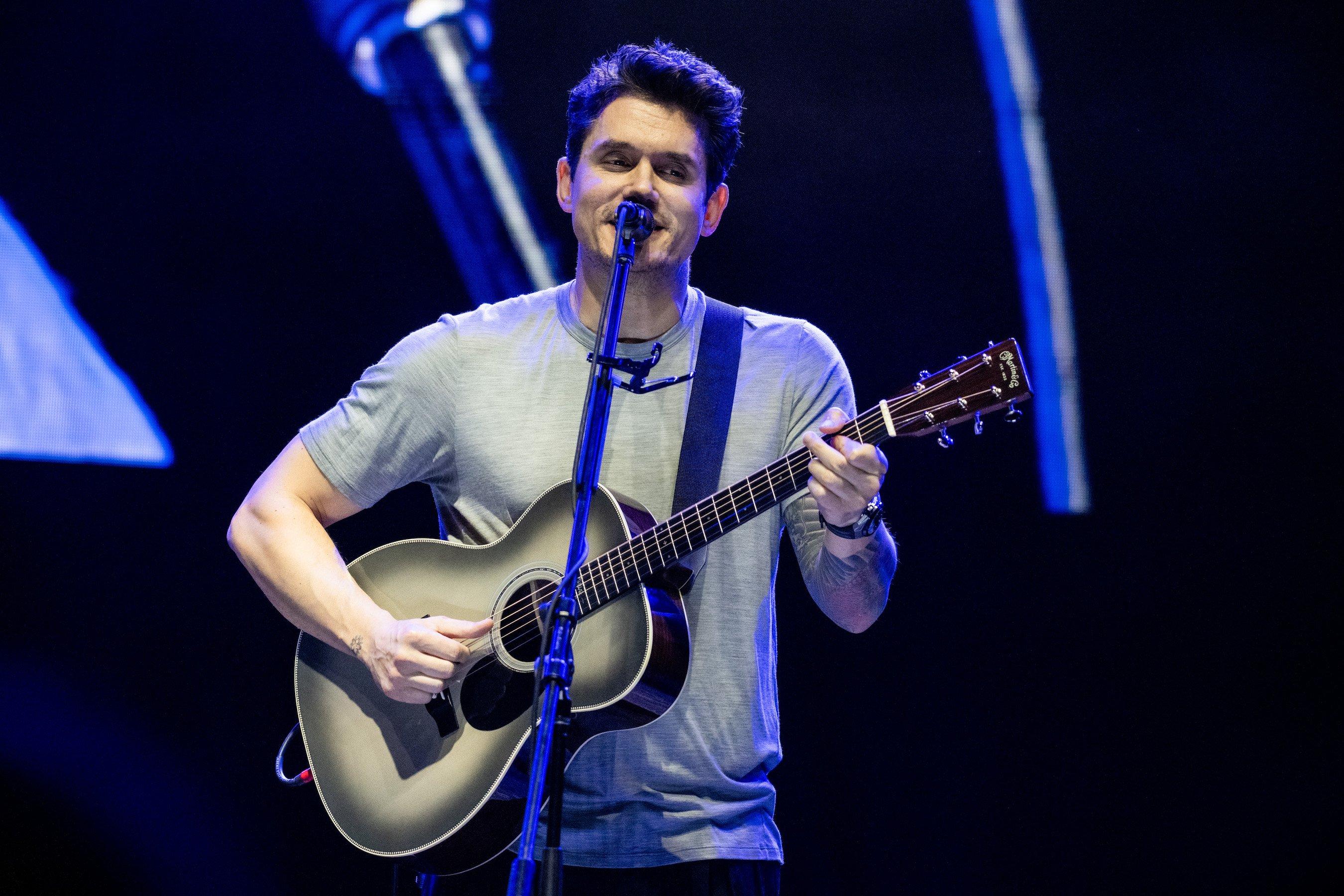

10 John Mayer Songs That Show His Versatility, From 'Room For Squares' To Dead & Co

As John Mayer launches his latest venture with Dead & Company — a residency at the Sphere in Las Vegas — revisit 10 songs that show every side of his musical genius.

At the 2003 GRAMMYs, a 25-year-old John Mayer stood on stage at Madison Square Garden, his first golden gramophone in hand. "I just want to say this is very, very fast, and I promise to catch up," he said with a touch of incredulity.

In the two decades that have followed his first GRAMMY triumph, it's safe to say that Mayer, now 46, has caught up. Not only has the freewheeling guitarist and singer/songwriter won six more GRAMMYs — he has also demonstrated his versatility across eight studio albums and countless cross-genre collaborations, including his acclaimed role in The Grateful Dead offshoot, Dead & Company. But the true testaments to his artistic range lie simply within the music.

Over the years, Mayer's dynamism has led him to work deftly and convincingly within a wide variety of genres, from jazz to pop to Americana. The result: an elastic and well-rounded repertoire that elevates 2003's "Bigger Than My Body" from hit single to self-fulfilling prophecy.

From March 2023 to March 2024, Mayer took his protean catalog on the road for his Solo Tour, which saw him play sold-out arenas around the world, mostly acoustic, completely alone. The international effort harkened back to Mayer's early career days, when standing alone on stage, guitar in hand, was the rule rather than the exception. Just after his second Solo leg last November, Mayer added radio programming and curation to his resume via the launch of his Sirius XM channel, Life with John Mayer. Fittingly, XM bills the channel (No. 14) as one notably "defined not by genre, but by the time of day, as well as the day of the week."

Mayer's next venture sees him linking back up with Dead & Company, for a 24-show residency at the Sphere in Las Vegas from May 16 to July 13. In honor of his latest move, GRAMMY.com explores the scope of Mayer's musical genius by revisiting 10 essential songs that demonstrate the breadth of his range, from the very beginning of his discography.

"Your Body Is A Wonderland," Room For Squares (2001)

The second single from Mayer's debut album, "Your Body Is A Wonderland" became an almost instant radio favorite like its predecessor, "No Such Thing," earning Mayer his second consecutive No. 1 on Billboard's Adult Alternative Airplay chart. The song's hooky pop structure provided an affable introduction to Mayer's lyrical skill by way of smart, suggestive simile and metaphor ("One mile to every inch of/ Your skin like porcelain/ One pair of candy lips and/ Your bubblegum tongue") ahead of Room For Squares' release later that June. The breathy hit netted Mayer his first career GRAMMY Award, for Best Male Pop Vocal Performance, at the 45th Annual GRAMMY Awards in 2003.

In recent years, Mayer — who penned the song when he was 21 — has chronicled his tenuous relationship with "Your Body is a Wonderland" in his infamous mid-concert banter, playfully critiquing the song's lack of "nuance." Following a perspective shift, Mayer has come to embrace his self-proclaimed "time capsule"; it was a staple of his set lists for his Solo Tour.

"Who Did You Think I Was," TRY! - Live in Concert (2005)

The product of pure synergy and serendipity, the John Mayer Trio assembled after what was intended to be a one-time stint on the NBC telethon, "Tsunami Aid: A Concert of Hope," in 2005. The benefit appearance lit the creative fuse between Mayer, bassist Pino Palladino and drummer Steve Jordan — who, over the years, have also played alongside the singer on his headline tours.

The John Mayer Trio propelled its eponymous artist from pop territory to a bluesy brand of rock 'n' roll that then demonstrated his talent as a live guitarist to its greatest degree yet. The Trio's first and only release, TRY! - Live in Concert, was recorded at their September 22, 2005 concert at the House of Blues in Chicago.

Mayer acknowledges his abrupt sonic gear shift on TRY! opener, "Who Did You Think I Was." "Got a brand new blues that I can't explain," he quips, then later asks, "Am I the one who plays the quiet songs/ Or is he the one who turns the ladies on?"

"Gravity," Continuum (2006)

Though "Waiting On the World to Change" was the biggest commercial hit from 2006's Continuum, "Gravity" remains the pièce de résistance of Mayer's magnum opus. Its status as such is routinely reaffirmed by the crowds at Mayer's concerts, whose calls for a live performance of his quintessential soul ballad can compete even with Mayer's mid-show remarks.

The blues-tinged slow burn marries Mayer's inimitable vocal tone with his guitar muscle on a record that strides far beyond the pop and soft rock of his preceding studio albums. Though Continuum builds on the blues direction Mayer ignited with TRY!, it does so with greater depth and technique, translating to a concept album, sonically, that evinces both his breakaway from the genres that launched his career and his skill as a blues guitarist — and "Gravity" is a prime example.

"I'm very proud of the song," Mayer mused on his Sirius XM station. "It's one of those ones that's gonna go with me through the rest of my life, and I'm happy it's in the sidecar going along with me."

"Daughters," Where the Light Is: John Mayer Live in Los Angeles (2008)

"Daughters" wasn't Mayer's first choice of a single for his sophomore LP, 2003's Heavier Things, but at Columbia Records' behest — "We really want it to go, we think it can be a hit," Mayer recalled of their thoughts — the soft-rock-meets-acoustic effort joined the album rollout. Columbia's suspicions were correct; "Daughters" topped Billboard's Adult Pop Airplay in 2004 — his only No. 1 entry on the chart to date.

But "Daughters" didn't just enjoy heavy radio rotation — it also secured Mayer his first and only GRAMMY win in a General Field Category. The Heavier Things descendant took the title of Song Of The Year at the 47th Annual GRAMMY Awards in 2005, helping Mayer evade music's dreaded "sophomore slump."

While the studio version may be the GRAMMY-winning chart-topper, Mayer's live rendition of "Daughters" during his December 8, 2007 performance at Los Angeles' Nokia Theater for Where the Light Is: John Mayer Live in Los Angeles compellingly demonstrated the power of the song — and his acoustic chops.

"Edge of Desire," Battle Studies (2009)

Come 2009, what critics almost unanimously proclaimed to be Mayer's biggest musical success had become his Achilles heel; everyone wanted another Continuum. But as they were to learn, Mayer never repeats himself. Thus came Battle Studies.

Born from a dismantling and transformative breakup, his fourth studio album arguably only becomes fully accessible to listeners after this rite of passage. Mired in introspection and pop rock, Battle Studies broadly engages with elements of pop with a sophistication that distinguishes it from Mayer's earlier traverses in pop and pop-inflected terrain.

His artistry hits a new apex on "Edge of Desire," a visceral and tightly woven song that remains one of the strongest examples of his mastery of prosody — the agreement between music and lyrics that results in a resonant and memorable listening experience.

"Born and Raised," Born & Raised (2012)

On the title track of his fifth studio album, Mayer distills growing up (and growing older) into a plaintive reflection on the involuntary, inevitable, and, in the moment, imperceptible phenomenon. He grapples with this vertigo of the soul on a record that, 12 years later, remains among his most barefaced lyrically.

The tinny texture of a harmonica, heard first in the intro, permeates the song, serving as its single most overt indicator of the larger stylistic shift that Born & Raised embodies. The 12-song set embraces elements of Americana, country and folk amid simpler-than-usual chord progressions for Mayer, whose restraint elevates the affective power of the album's lyricism.

"Born and Raised - Reprise," with which Born & Raised draws to a close, is evidence of Mayer's well-demonstrated dexterity. In its sanguine, folk spirit, the album finale juxtaposes "Born and Raised" both musically and lyrically. "It's nice to say, 'Now I'm born and raised,'" Mayer sings as the last grains of sand in Born & Raised's hourglass fall.

"Wildfire," Paradise Valley (2014)

Even before Paradise Valley hit shelves and digital streaming platforms, the cowboy hat that Mayer dons in the album artwork intimated that the hybrid of Americana, country, and folk he embraced on Born & Raised wasn't going anywhere — at least not for another album. The sunbaked project was a gutsy sidestep even further away from his successful commercial formula, and finds him expanding his stylistic fingerprint across 11 tracks that run the gamut of American roots music.

"Wildfire," the breezy toe-tapper with which Paradise Valley opens, grooves with Jerry Garcia influence. It is therefore unsurprising that many interpret "We can dance with dead/ You can rest your head on my shoulder/ If you want to get older with me," to be a lyrical nod to the Dead. Perhaps uncoincidentally, Mayer's invitation to become a member of Dead & Company came one year after the release of Paradise Valley.

"Shakedown Street," Live at Madison Square Garden (2017)

There is perhaps no better example of Mayer's dynamism than his integration in Dead & Company. The Grateful Dead offshoot, formed in 2015, intersperses Mayer among three surviving members of the band — Bob Weir, Mickey Hart, and Bill Kreutzmann — as well as two more newcomers, Oteil Burbridge and Jeff Chimenti. Mayer's off-the-cuff guitar solos and vocal support at Dead & Co's concerts are the keys that have unlocked a new plane of musicianship for Mayer, the solo artist.

This is evident on "Shakedown Street," a staple of The Grateful Dead's – and now, Dead & Company's – set lists. The languid, relaxed number gives Mayer the space to improvise guitar solos and use his vocals in a looser style than how he sings his own productions, all while feeding off the energy of his fellow band members. In addition to being one of The Dead's best-known songs, "Shakedown Street" is also the name of the makeshift bazaar where "Deadheads" socialize and sell wares ranging from grilled cheeses to drink coasters emblazoned with The Grateful Dead logo outside Dead & Company concerts.

Mayer's long, strange trip with (and within) the jam band has cross-pollinated his and The Grateful Dead's respective fandoms, attracting scores of Dead & Co listeners to his own headline shows, and vice versa. The takeaway: Mayer's involvement with Dead & Company offers a new, comparatively more rugged and improvisational lens through which to view his artistry.

"You're Gonna Live Forever in Me," The Search for Everything (2017)

"You're Gonna Live Forever in Me" evokes the sense of walking in, unexpected and undetected, to one of Mayer's writing sessions, watching him sing the freshly-penned piano ballad. This is owed to the song's abstract lyricism, the sentiment of which is deeply personal and universally accessible — a juxtaposition that's not often easy to achieve in songwriting. (Take, for example, "A great big bang and dinosaurs/ Fiery raining meteors/ It all ends unfortunately/ But you're gonna live forever in me.") But the studio version of "You're Gonna Live Forever in Me" also happens to be the original vocal take, adding to the feeling that Mayer is fully engrossed in a moment of poignant reflection mediated by music.

"I sat at the piano for hours teaching myself how the song might go. I sang it that night, and that was it…I couldn't sing the vocals again if I tried," Mayer recalled in a 2017 interview with Rolling Stone.

Mayer's lilted, Randy Newman-esque singing on the track finds him unintentionally but impactfully adopting a vocal technique distinctive from anything he's ever done before.

"Wild Blue," Sob Rock (2021)

Buoyed by a honeyed hook and slick production from No I.D., "New Light" was the unequivocal commercial standout of Sob Rock, a soft-grooving pastiche of '80s influence. Though the catchy pop-informed number finds Mayer stylistically diversifying by working with "The Godfather of Chicago Hip-Hop" (whose credits include Kanye West, JAY-Z, and Common, to name just a few), a look beyond the Sob Rock frontrunner reveals evidence of more sonic experimentation on the album.

Cue "Wild Blue." In its hushed, double-tracked vocals, the song plays like a love letter to JJ Cale. Mayer's whispery vocal emulation of the rock musician yields another new, but still polished, strain of John Mayer sound.

With hints of the '70s embedded within its taut production, "Wild Blue" is a beatific semi-departure from its parent album's '80s DNA. Together, they evince Mayer's ability to work not only across genres but also across sounds from different decades in music — further proof that his artistic range is both broad and timeless.

A Beginner’s Guide To The Grateful Dead: 5 Ways To Get Into The Legendary Jam Band

Photo: Shawn Hanna

interview

Incubus On Revisiting 'Morning View' & Finding Rejuvenation By Looking To The Past

More than two decades after 'Morning View' helped solidify Incubus as a rock mainstay, Brandon Boyd and Michael Einziger break down how rerecording the album for 'Morning View XXIII' "reinvigorated" the band.

By 2001, alt-rock heroes Incubus were on the verge of something big. Their third album, 1999's Make Yourself, was a crossover hit, thanks to singles "Stellar," "Pardon Me" and "Drive," all of which were on constant rotation on alt-rock radio and MTV. To capitalize on the momentum and record a follow-up, the band rented a beachside mansion on Morning View Drive in Malibu instead of recording in a traditional studio.

For a little over four weeks, the band lived together in that beachside mansion, working on songs day and night, creating what would become their best-selling record, 2001's Morning View. As frontman Brandon Boyd remembers, the carefree setup helped Incubus create without any pressure to match Make Yourself: "For whatever reason, I never felt like we had to come up with something better or else it'd all be over. It was just fun and exciting."

The result was an album that moved them further away from the heavy nu-metal sound of their earlier records and leaning into their new mainstream appeal. Morning View debuted on the Billboard 200 at No. 2, kickstarting a trend that would continue with each of the band's preceding albums landing in the top 5 on the all-genre albums chart. By evolving their sound on Morning View, Incubus found connection with a wider audience and changed the trajectory of the band.

Twenty-three years after Morning View was originally released, Incubus are commemorating the album with a U.S. tour and a re-recorded version titled Morning View XXIII, out now. While bands tend to celebrate anniversaries with deluxe reissues and remasters, Incubus uniquely decided to rerecord the album in order to capture these songs as they are now — that is, fully evolved and gracefully aged.

Recorded in the same mansion on Morning View Drive in Malibu with Boyd on vocals, Michael Einziger on guitars, Jose Pasillas on drums, Chris Kilmore on turntables and keys, and newbie Nicole Row on bass, Morning View XXIII sees the band stepping back into the snapshot of an album and paying homage their most successful recordings. These are not remixes or carbon copies; these recordings are a representation of wizened alt-rock veterans Incubus are now. As a result, it has rejuvenated the band: "There's this feeling of, 'Oh wow, there's still a lot of life in this,'" Boyd adds.

Mostly, Morning View XIII remains faithful to the original, with subtle differences throughout. Others you'll notice, like the extended swelling intro in album stand-out "Nice to Know You," or the heavy riff return in "Circles." Overall, the band sounds as youthful as they ever have, excited to pay respect to an album that shaped both them and their fans.

Ahead of XXIII's release, GRAMMY.com caught up with Boyd and Einziger over Zoom to talk more about the project, the album anniversary, and tapping into that exuberant energy to pave the way forward into the band's next era.

This interview has been edited for length and clarity.

First of all, welcome back to the U.S., I know you've been out of the country for a while. And you guys just played "Kimmel" and sounded fantastic. What's it like being Incubus in 2024?

Brandon Boyd: It's a trip. There's this feeling that we've been… I don't know if the right word is reinvigorated… I think it's probably a number of factors that we have to include. But the one that feels the most appropriate to mention is the fact that Nicole Row joined our band. It started as her filling in for Ben Kenny on Ben's suggestion, and fast forward to a few months later and she's become an actual member of the band.

It's just been so much fun getting to know her, but also getting to know her through the lens of being on stage together and traveling and playing shows all over the world. She's a phenomenal player, and she's a wonderful presence and personality. And it seems like our longtime listeners have fully accepted her and welcomed her into the fold with open arms.

Mike Einziger: I couldn't agree more. It's kind of a combination of things for me, but definitely Nicole. Nicole's presence has reinvigorated us in a bunch of different ways. She's a bit younger than us…

Boyd: Just a bit. [Laughs.]

Einziger: …And super talented, fun to play with, and fun to be around. That's having a really great effect on all of us as a collective. But also, as you mentioned, we just got back from five weeks touring in Asia, Australia and New Zealand — these are parts of the world we haven't been to in quite some time, not since the pandemic. And you know, I'm 47 now, and it's pretty crazy to be this age and traveling that far away from our country and city of origin to be playing in front of tens of thousands of people who care about our music.

It's like, the older I get, the more I can't believe and am astonished and appreciative and humbled by the level of enthusiasm for this music that we wrote so long ago. It's just a feeling of appreciation and humility to be in this position to now consider writing new music and keeping the dream alive, as it were.

It sounds like you've tapped into this youthful energy. That's sort of the vibe I've been getting with Morning View XXIII. When you were rerecording this record, did you feel like you wanted to reach back to the kids you were 23 years ago when you originally recorded?

Einziger: It's really interesting because, to be totally honest, I wasn't totally enthused about the idea in the beginning. When we first started talking about it, it kinda seemed like, "Why would we do this?" But we ended up playing Morning View at the Hollywood Bowl here in Los Angeles, and when we played that music in front of people, it felt really different than I imagined it would.

That experience shaped my perspective on the idea of rerecording the music. In a strange way, it was a new experience, but it also [felt] like visiting really old friends. It was just fun. That's really the only way to describe it.

It was so much fun rerecording those songs, being conscious of how we were changing certain aspects but also not really caring at the same time. This is our music. We can do whatever the f— we want with it. People can like or not like it. Whatever. We're gonna have a good time putting this together. To me, it was all about that experience of just enjoying it and reliving that music, and also making it new at the same time.

Boyd: I agree with you 100 percent, Mike. There's one small factor from a selfish point of view that I feel compelled to mention: the songs from Morning View were getting harder and harder for me to perform live over the last 10 years. Part of it was because of the process of aging. We wrote these songs when we were in our 20s, and now we're all in our late 40s trying to perform them [Laughs].

And then on a boring physiological human level, I had broken my nose twice as a kid and I learned to sing through one nostril. My other nostril I could never breathe through. I made the decision to have my septum repaired in late 2019. I knew it was gonna take some time for my face to heal completely. The global pandemic forced us to stay home, and I got this really interesting period of time to let my surgery heal and to learn how to breathe and sing out of two nostrils.

By the time we got to the rerecording of this record and I started doing my vocals, I had access to my voice again for the first time in what felt like over 10 years. And so now we're performing these songs again, and it's like somebody gave me back this breath capacity and this space on the inside of my face to access these things. It feels very different now, and I'm feeling invigorated again for sure.

Einziger: So much of musical performance is not thinking about what you're doing. It's more about expressing yourself and not worrying about if what you're playing is hurting you.

Boyd: The music is kind of spilling out of us again like it did when we were in our 20s.

Einziger: We'll just continue to make it harder for ourselves when we get even older, because we constantly are like, "Wow, we wrote all this music that is extra hard for a 40-something to play," and now we'll write music that is extra hard for 60 somethings to play and that'll be challenging in the future… but we'll be lucky if we get there. [Laughs.]

It's so interesting to hear how these songs have grown over the years. Is this something you wanted to capture with Morning View XXIII? What are your thoughts on how these songs have evolved and what time has done for your band?

Einziger: It's interesting because we didn't go into the recording process of rerecording Morning View with this intention that we were going to make new versions of the songs and, like, reimagine them so much as we went in there and just played them how we play them now. There were some things that we changed around a little bit, but it became obvious that there are certain parts of the songs that we play now that are just different than when we were recording them [23 years ago]. Sometimes we had to go back to the original recording and be like, "Oh wow, we actually don't play it like that."

Were there things you wanted to do differently this time around that you didn't or couldn't do in 2001?

Einziger: No, just there were parts that we play now — that I play now, for example — that Brandon would point out to me and he'd be like, "I don't think you play it like that on the recording," and I'd be like, "Of course I did! That's ridiculous. What are you talking about?"

Then we'd go back and listen to it and I'd be like, "Oh yeah, I actually did play it that way." We weren't overly concerned about that. We weren't trying to do this verbatim recitation of what we had done in the past. If we're playing it this way now, that's how we're gonna record it. And we did. It was fun.

So you didn't worry about "tampering" with the songs?

Einziger: Nah, like who f—ing cares! People will say "I wish they didn't change it" and it's like, we didn't change anything. We just made a different recording, but the original version will never go away. It will always be there, unless some cataclysmic event happens and wipes out all humanity. Then we have a bigger problem.

I remember reading something about how you wanted to separate yourselves from the nu-metal scene in 2001. Did you feel a sort of pressure to stand out when you were originally writing for Morning View? Do you care about that anymore?

Einziger: No. That s— makes me laugh when I think about it now. There was all this dumb, macho energy going on. We didn't want to be associated with that energy, but it's not really up to us to decide that anyway. We're expressing ourselves, we're making the music that we make and it's kind of up to everyone else to figure out.

But we ended up touring with a lot of those bands. We spent the whole early part of our career playing the Ozzfests and touring with bands like the Deftones — who I love — and System of a Down, Korn, and it just so happened that we had a lot of audiences in common. And I'm super grateful for that. It was an interesting musical time, and we made a lot of great friends, and we found an audience that we really connected with.

Boyd: I think the part about it that bothered me was more the fact that we didn't have a say in how our band was categorized. One of the things that's so attractive about being in the band — and I felt the same way when we were younger — is that, for better or worse, what we're presenting is coming directly from us. We're not a product of a team of producers and songwriters, which you see is sort of endemic to the music industry.

There's a lot of popular music that comes from think tanks. We're five people that go into a room, put our heads together, and what you hear is the result of that day. And there's something really cool about that. There's true self-authorship. And so when there were labels that were put onto us and associations with other bands, it felt like some of that self-authorship was being taken away.

It would be different if the labels were things that I associated more with. But when I was seeing sort of the terminology and labels that were being used to describe our band, I was like, "What the f—, that's not what we're doing! Ew!" It just felt icky to me.

But I was also — as we all are in our late teens, early 20s — kind of in a self-righteous period of time in my life, so it's very possible I was taking myself and our band a little too seriously. I feel a deep appreciation that anybody listened to what we did in any capacity. Associations be damned.

It doesn't really matter at the end of the day. If people are being exposed to it, then choosing to like it and make it a part of their experience, it doesn't f—ing matter what it's called, you know?

And the music speaks for itself.

Boyd: At the end of the day, yes.

Einziger: I think how I felt about this has evolved over the years. There's a handful of bands that we came up alongside, like Deftones, System of a Down, and Korn — including ourselves — we all somehow found a way to really connect with an audience. All of us are still making music. There's still a vibrant scene.

Why is Morning View special to you? Why do all of this for this particular album?

Boyd: When we were writing and recording this record [in 2001], our band caught a gust of momentum for what felt [like] the first time, where we were collectively like, "Woah, we get to write music as our job." And there was something really exciting and humbling and fun about that.

When we were writing Morning View, our song "Drive" from the record before it [Make Yourself] was climbing the charts really fast and they were playing it on MTV and all over the radio. To even have a whiff of that creative and career momentum at the same time is a real blessing, and I'm so grateful that we got to experience that.

When Morning View came out, the momentum just exploded. So this album means a lot to this band, not only from a career point of view but also just from the way it shot us into a trajectory. It was the record that sent us off into space, so to speak.

Einziger: Yeah, it was a heavy experience for everybody. I had this idea that I didn't want us to make what became Morning View in a recording studio. I wanted us to do it in a house, in a place that wasn't designed to make music. I loved the idea of taking a space that wasn't intended for that purpose and commandeering it into a space where we made music.

I got a lot of push back from our record label and our manager at the time. Nobody wanted us to do that. Nobody thought it was a good idea. It was gonna cost a lot of money to do it and the quickest, safest route from point A to point B was where everyone else wanted us to go. But I was very, very adamant that we not do it that way, and we somehow wrangled enough support to get the funding and find the right place to do it, which was that Morning View house.

Having that confidence and vision to be able to say, "No, f— you, this is how we're going to do it," and then have it be super successful, that was a big lesson to me and for all of us that we need to follow our vision. For better or worse, whatever risk it's going to be, that's how great s— happens. We just dove into it full on and fulfilled that vision.

It felt awesome to have that vision and have the record be successful. It was a fun experience, and I'm just really glad that we did it. It was life-changing for all of us.

Why Weezer's 'The Blue Album' Is One Of The Most Influential '90s Indie Pop Debuts