Welcome to Random Roles, wherein we talk to actors about the characters who defined their careers. The catch: They don’t know beforehand what roles we’ll ask them to talk about.

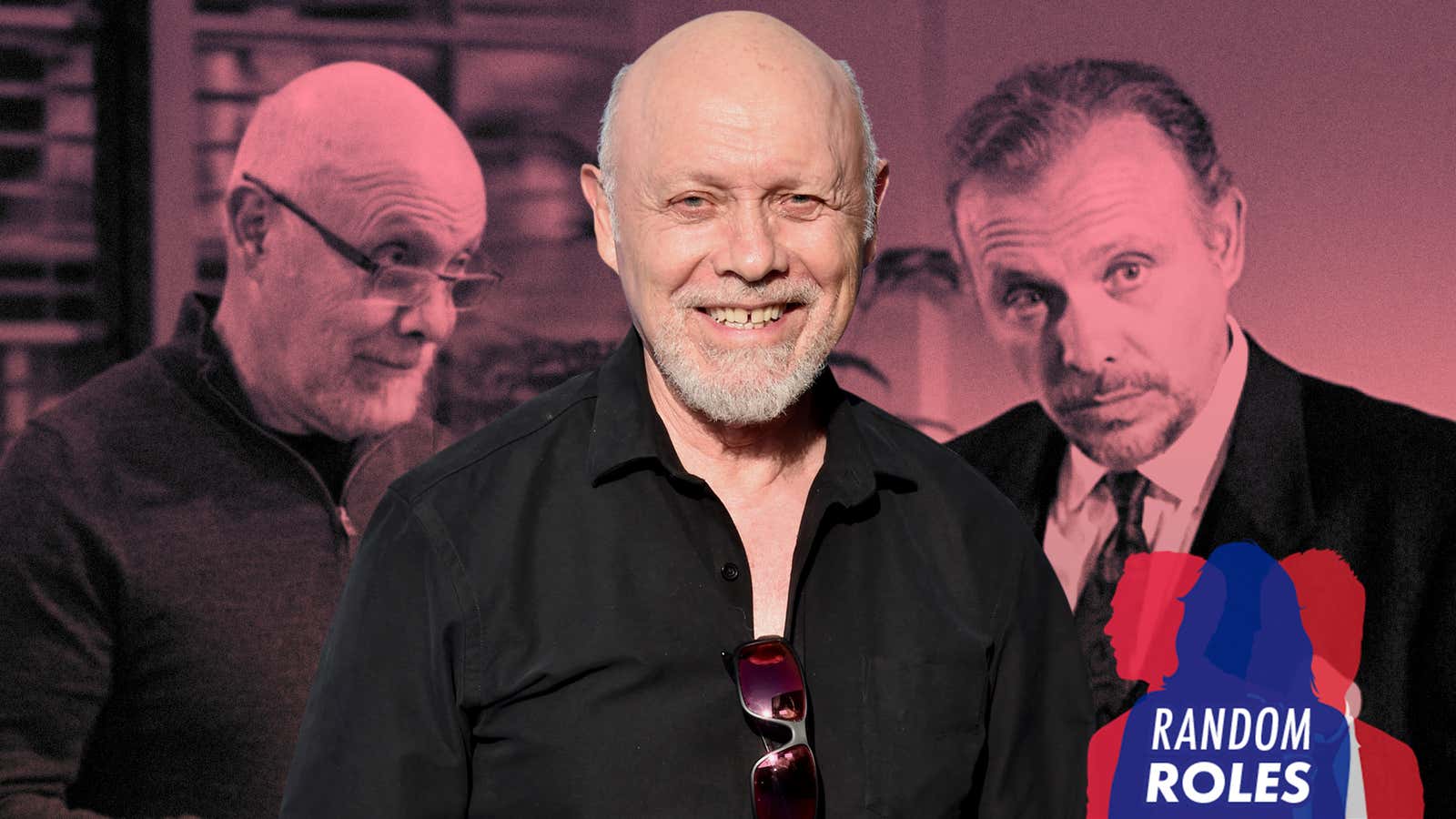

The actor: With a career that began in the theater and subsequently traveled through countless film and television performances, Hector Elizondo happily carved himself a spot as a self-described “whatshisname,” securing a steady stream of work—including an acclaimed turn in 1974’s The Taking Of Pelham One Two Three and an appearance in a much-praised episode of All In The Family—while generally staying out of the spotlight. That situation changed somewhat in 1990, when Pretty Woman—one of Elizondo’s 18 film collaborations with director Garry Marshall—became a box office phenomenon and brought him a Golden Globe nomination. Elizondo has continued to get all the work he can handle. Among myriad other roles, he has been a regular on the Tim Allen sitcom Last Man Standing since 2011, following the show from its original home on ABC to its current home on Fox. In honor of that series’ final season, Elizondo sat down with us for a long-overdue Random Roles interview.

Last Man Standing (2011-present)—“Edward ‘Ed’ Alzate”

A.V. Club: You’ve been playing Ed for quite a number of years at this point. How do you feel that Ed has evolved over the run of Last Man Standing?

Hector Elizondo: The thing about Ed that’s interesting is that when they need to fill up a hole, they have Ed. [Laughs.] He can be the generous guy or the stingy guy. The hard-ass guy or the easy-going guy. The soft-hearted guy or not. At first I said, “No, there’s no arc there for me!” But I got accustomed to that, and that’s a lot of fun.

Ed is a bit of a mystery to himself because, really, he doesn’t know what to do with the rest of his life, ultimately. And that’s a little close to home for a lot of people. He has a lot of money, he doesn’t have to work, he’s got all these stores. So what does he do at this point? He likes to stay engaged somehow. One of the problems with success is that you have so many options. When you have lots of options, then you’re faced with some real difficult questions. So I think Ed enjoys his success sometimes, but mostly he’s suffering from that… and also, I think, from a perpetual acid reflux. Pepto Bismol is used a lot on this show. [Laughs.] For me, I’m generally more interested in character. But I can make you laugh without a joke, just by looking at you. You see? I just did it.

AVC: You did. Even with that gift, though, you’ve had the opportunity to get a bit dramatic here and there on the show.

HE: Yeah, well, that’s an easy ball to hit. The more difficult ball is comedy. That’s the hardest thing to do. It’s harder to write, I think it takes more consideration to execute, and you have to have timing.

AVC: How did you find your way into Last Man Standing? Did they come looking for you specifically, or were they auditioning?

HE: No, one thing I haven’t done in 150 years is audition. Much to the consternation of perhaps some of the people who’ve worked with me! [Laughs.] Also, I don’t do that well, so fortunately I don’t have do it!

AVC: It’s remarkable how much life this show has had in it, landing on two networks and lasting for 10 years.

HE: This is a show that’s proven we have a good chin, as they say in boxing, and quite a resilient group of people. Of course, there’s the producers and the writers, but then there’s the ne’er-do-well actors that we are, trying to be the delivery system for their ideas. But it’s been more than a surprise to us. It’s stunning to think that it was 10 years ago that we started this show. The other thing that’s remarkable is how much effort it’s taken to put life into that idea! It just shows that we had good people up front. Originally, we didn’t think it’d get through the first year, there was just so much that happened and it was so dramatic behind the scenes. But we pulled it through, and I guess we’ve become established, as they call it. [Laughs.] As I understand it, it’s very hard not to see us on the air!

AVC: Now that the end is finally nigh, as far as Ed’s story goes, is there anything that hasn’t been tackled that you’d hoped would be?

HE: Yeah, but… [Hesitates.] I wish we would’ve had more of an opportunity to tackle what eventually turned out to be the horror show of [the Trump] administration. I wish we would’ve tackled that. But given the givens, we… didn’t do that. And we did other things. We tackled it in a way that just braided it into a story, not making it into the main story. It was an opportunity that I thought was somehow missed, but it was a decision that was made somewhere else. But I think it was a very important thing to discuss at the dinner table in some way that made you laugh, you know? The way Norman Lear would’ve made you laugh. That would’ve been a terrific thing. And it could’ve saved a lot of heartache in the populace that seems now… They’re easily confused, shall we say. To be politic about it. [Laughs.] Even to discuss the fact that it’s been proven that the moon is not made of green cheese, and the reason is that there’s something called science, and that we have been there, we have photographs, and it is not green cheese! But somehow you can still convince people of the moon being made of green cheese.

But I do think that we’ve covered very good bases considering that it’s a show for the family. We stayed true to that: It was a show that anybody could tune into, that the kids could watch. We covered a very wide demographic. And that’s what made it successful, ultimately. Mr. Allen made sure it stayed on track, so a lot of credit goes to him. And, of course, Nancy [Travis] and the rest of the cast, we were very happy that it was something that we didn’t have to be at all ashamed of. We can be proud of the show.

AVC: It’s one of those shows where a lot of people thought that it was something other than what it was, and the ones who actually decided to watch it discovered that it wasn’t actually that at all.

HE: That’s right! Somehow it was braided in there every week a story for everybody. Essentially, it was to laugh at the human condition. Here are are, we’re primates, still in the process of developing. Why are we funny? [Laughs.] You take a trite situation, and it reflects the human condition. How do people do something that’s very difficult, if not almost impossible, which is to live as a unit under the same roof, and yet somehow make it to the next day with hope in your heart, knowing that the sun will shine or that the rain will come? Because the rain is as important as the sun. And I think the show does that, and I’ve been very pleased by that. I’ve been very happy with it.

The Fat Black Cat (1963)—“Dinner Party Guest”

The Vixens (1969)—“Inspector”

Valdez Is Coming (1971)—“Mexican Rider”

AVC: We try to ask everyone about their first on-camera role, and according to IMDB, it looks like yours was in The Fat Black Pussycat.

HE: Wow! Is that what it was called?

AVC: It was if you played a guest at a dinner party.

HE: No, I was a cop. A detective. And now that I’m talking about it, it wasn’t called that! [Laughs.] I was a stage actor in New York, and they gave me pages for an independent movie, and I was this cop at a dinner table, asking questions. I got a hundred bucks, I think it was. I’d completely forgotten about it, but now… I think it was called The Vixens?

AVC: The Vixens was supposedly after The Fat Black Pussycat.

HE: I’ll take your word for it. [Laughs.] Someone actually took a picture of an ad for The Fat Black Pussycat on their cell phone and sent it to me, so I suppose that’s the first thing… unless you can find an old kinescope from 1946 or 1947 of Wendy Barrie in The Okey Dokey Ranch House.

AVC: Really?

HE: Yeah, I was 10 years old, and I appeared in that for a segment as some kid running around for some reason. So, really, my first appearance was in ’46. You want to be very specific! [Laughs.] But I had no idea that I was doing it. In other words, I was such a kid that I knew there was free stuff around. There was free ice cream, I think. But it took a long time. [Whining.] “It’s getting hot! I wanna go home now!”

AVC: How did you find your way into a career in acting in the first place? Was it something that you’d always wanted to do, or did you just kind of stumble into it?

HE: No, I didn’t stumble in. I was always involved in music. Music, sports, and girls. Not in that order necessarily. [Laughs.] In other words, I was a wastrel. I danced jazz in a company in the early ’60s, so tangentially I touched upon theater. You know, if you’re in the dance world for a minute, somebody’s gonna say, “Here are tickets to a play!”

So I went to a play, A Taste Of Honey it was called, and I’m this kid sitting in the box seats with my friend—and this is true: Later on, I appeared and was starring in that same theater on Broadway—and I was mesmerized by the live theater. I said to my friend, “This is terrific! Look at this: people moving and talking and walking… There’s a vibration here!” And out comes this character in a sailor suit, he cocks his hat, he sings a song and does a little dance. And I go, “I know that jive son of a bitch! He went to my high school!” [Laughs.] And that was Billy Dee Williams. And there he was on Broadway! I said, “What the hell? Son of a gun, I can do that!” [Laughs.]

No, but I was struck by the theater experience and the immediacy of it, and eventually one thing led to another. I said, “Huh, you really have to study this stuff.” So I did. I started. And I got a break—my first theatrical production in 1961—with the help of a lovely man, the late Ed Sherin, who was the director. Later on, he directed me in my first big movie that I did, Valdez Is Coming, with Burt Lancaster, another lovely man. May they both rest in peace. But, yeah, that’s how it started: with the Equity Library Theater in ’62. It was a production of Mister Roberts. And I’ve been involved in acting ever since. [Pause.] With great periods of non-involvement.

The Great White Hope (1968-1970)—various characters

AVC: You were in the Broadway cast of The Great White Hope that Edwin Sherin directed.

HE: Wow, what an experience that was. We started that at the Arena Stage in Washington and shaped it there. So I was with The Great White Hope for a long time. I had five roles, running up and down the stairs, for $200 a week… and I was just as happy as can be to be part of that incredible cast. I mean, it was like a big moving picture of America! And the people I met… Muhammad Ali came to see the show, Louis Armstrong came to see the show. It was a groundbreaking play, and it was very important to me. And Ed Sherin was a very important person to me. He was a terrific guy. And a committed guy. Greatly involved with the industry. He helped make the DGA better. [Long pause.] I never got in touch with Jane [Alexander, Sherin’s widow] to send my condolences, dammit. No one seemed to know how to get in touch with her. It upset me greatly.

The Landlord (1970)—“Hector”

Pocket Money (1972)—“Juan”

Courage (1986)—“Nick Miraldo”

AVC: Even before you did Valdez Is Coming, you worked with Hal Ashby on The Landlord.

HE: Oh, yeah, I think I was in that for a second. [Laughs.] I was in it, and then a bunch of scenes were cut out, and… I think I was cut out of that! I think you see me running down the street with a bunch of people. But I had a couple of stoop scenes. I barely remember it, quite frankly. That’s where I met Beau Bridges, yeah! Lovely man. And he became a pal. We’ve done a couple of things together. That has to be early ’70s. And shortly after that I did Pocket Money with Lee Marvin and Paul Newman. Two guys who weren’t bad, you know? [Laughs.] They were cool. Cool people.

AVC: You’ve gotten to work with a lot of cool people. Throughout your career, certainly, but particularly in those early years.

HE: Who knew? I got to be in bed with Sophia Loren [in Courage]. I should’ve paid more attention! [Laughs.] Lovely lady. Terrific. All she talked about was food. Which was great. Food, cooking… How can you not like somebody like that?

All In The Family (1972)—“Carlos Mendoza”

AVC: You appeared in a very memorable episode of All In The Family in the show’s second season. Archie Bunker gets stuck in an elevator with a Black businessman, a secretary, and you as a Puerto Rican janitor, and your pregnant wife, who goes into labor in the elevator.

HE: That was a turning-point episode. That episode saved the show; they were about to cancel it. Again, who knew? I didn’t! [Laughs.] I knew nothing about it until I read that story in Norman Lear’s autobiography [Even This I Get To Experience], where he gave all the details. When you read his memoir, he talks about it, and how there was a big to-do over this episode. I was blissfully ignorant of that. For me, it was just a job. I was hired in New York City, where I was doing stage work, of course, and in between plays. I came to the west coast—not for the first time—and I used to love those jaunts, those trips for a week or two. I’d do a job and go back home.

I knew nothing—or very little—about television or the world of producers, directors, how it was formed, especially situation comedies. But I knew that All In The Family attracted a great deal of attention because it seemed to be right on the mark on time, which is something that television had never done before. It was a step or two behind the times. Norman Lear’s shows seemed to be right on time when it came to the subject matter and the topics, particularly the taboo topics. And he made you laugh! I said, “How the hell are they pulling this off?” Well, suddenly, there I was doing a show! But it was decades later when I read Norman’s book and discovered that this was a seminal episode: Not only did Carroll O’Connor win an Emmy, but the show was renewed and ran for however many more seasons after that.

But it was quite something to realize that there was drama going on behind the scenes. The only way that Carroll—who, by the way, was a wonderful fellow and a terrific writer—could create this seminal character was because he understood the character and never made fun of the character. He wasn’t a caricature. He was a character! How do you pull off something like that in a volatile time like that, with the Vietnam War and everything, and somehow become beloved? That’s the trick: to become beloved. Quite different from what we have now. [Laughs.] I mean, people loved Carroll! Now, [Archie Bunker] may have been ignorant about these social issues, and he had some absolutist ideas, but he was a good person and a good man who would never have thought for an instant of attacking the Capitol! He would’ve absolutely been in the front lines of people stopping that! But anyway, how they did that [with Archie Bunker] was really magical and quite artful.

While I was at rehearsals… Well, first of all, I realized that these were all theater people! In those days, that’s where your pool of talent came from: the theater. From Broadway, off-Broadway, repertory theaters… all these theater folk. And most of them were writers, so it was a very comfortable place to be in terms of their level of experience and commitment to the show. I realized how important it was for them to do a good show. I mean, at one point, you were getting 50 million eyes on an episode! It’s stunning. Fifty million people were watching that show at one time… and that’s why it was discussed around what they called the water cooler, right? In the offices, everyone was talking about All In The Family. And this episode was right on time. [Whispering.] “Did you hear what he said?” And yet they were laughing. These taboo subjects—which should not have been taboo—were being discussed and being laughed at!

But I understand that Carroll did not want to do [the episode]. He didn’t want to be stuck in an elevator. He didn’t think that would be successful, and he didn’t think it would make for a good show. He had to be convinced. In fact, it got so serious that, from what I can remember, there was some kind of litigation going on behind the scenes. He wanted to leave, and they had to convince him not to leave. Of course, that last scene, if you remember, when the camera pushed in on his face as he heard that baby cry, the baby that was born in the elevator… It made you cry. Carroll O’Connor made you cry just by a look and by something he said: “You got a little boy, huh?” It was incredible. Just stunning. It was an artful piece of work.

But as I say, it was interesting to read about it after the fact, because I was just doing my job! [Laughs.] I didn’t know anything at all about the real drama going on behind the scenes! Knowing that, though, makes it a richer experience for me. I didn’t know I was going to be part of TV history.

A.K.A. Pablo (1984)—“José,” director

AVC: You were also in the cast of the Norman Lear show A.K.A. Pablo, even if it definitely didn’t last as long. You also directed on the show.

HR: Yeah, I was… forced to volunteer, let’s put it that way. [Laughs.] Norman is very persuasive. I had more than my fair share of doubts about the efficacy of the show. It was a great, courageous try by Norman and ABC, but I was hired as an actor, and we helped flesh out this character. I think I was an agent. A Cuban Jew named José Shapiro, or something like that. By the way, that’s not a made-up thing. There’s a very strong contingent of Jews in Cuba. And most Americans had never heard of that. So I said, “Good! They’re going to have a little teaching moment!”

But after we did the pilot and two or three shows, there was—much to my chagrin—a change of director. I was shocked. Why change the director? She’s terrific! And Norman said, “Well, I think we’ve found someone else.” I said, “Norman, at this stage, now that we’re trying to get our sea legs on the show…” He says, “I’m looking at him.” I said, “Wait a minute! Whoa, just a second! I’m not interested in directing! [Laughs.] I’ve got enough on my hands to create this character and and work this job! How am I gonna do the show and be up in the control room?” Because if you’ll remember, in those days, if you were the director, you had to be in the control room. I said, “That’s schizophrenic! That’s a binary situation! How do I figure that out?” But he was very, very persuasive. “Don’t worry, we’ll have a technical advisor, a camera guy… I want you to stage the show. The actors have told me, ‘That’s the guy to direct!’” So the cast was the one who pointed the finger… and the parting director, too, for some reason!

I said, “Norman, that’s coaching. That’s not directing.” I like to work with actors because I love actors, and when they have a problem, I sort of sidle up and say, “Let me know if I can help you.” That’s all. And one thing leads to another, and before you know it, you’re helping on the side, whispering in people’s ears.

Especially in comedy, because comedy… [Takes a deep breath.] It’s more difficult than drama. [Laughs.] As the old actor was dying, with his friends around the bedside, one of them says, “What does it feel like, Moishe?” And he says, “Comedy is harder.” People never give comedy its due, because it makes them laugh. It’s easily digestible, so it must be easy to do. Not at all! It’s quite the opposite. But there I was, and my wife, bless her heart, she said, “Take a shot. Give it a go. What the hell, maybe you’ll like it.” And I tasted it, and.I didn’t like it. [Laughs.] I realized that, as a coach, I have great patience, I’m one-worldly, following the Buddhist chakras. I’m terrific. As a director, I have a tendency to be a little autocratic. But quietly so. “What do you mean you’re late? You’re not supposed to be late. Take your bowel movement a half-hour before, for heaven’s sake!” I guess coming from the theater, I had thin skin for any excuses. Norman was terrific, the cast was terrific, but there were just too many people in the cast. We gave it a shot, and then we went on our way. But Norman and I have stayed in touch. He’s a treasure in our business. Just a treasure.

The Taking Of Pelham 1-2-3 (1974)—“Grey”

HE: I’m looking at a poster somebody sent me for The Taking of Pelham 1-2-3, where I met the wonderful Walter Matthau, and we were having a chat… Well, he was actually giving me his two-minute lecture on why I shouldn’t smoke the cigar I was about to light! He’d had to stop smoking because he’d had a heart attack, and he was convinced that smoking was one of the reasons why he’d had it. He was tall, very laconic, and he was just a particular kind of man. So he says, “So listen, pal… Are you gonna light that thing?” And I said, “I have a feeling I’m not going to, Walter. I don’t think that’s gonna be good for my career!”

And upon my saying that word, he said, ‘Whaddaya mean ‘career’? Lemme tell ya something else! Don’t have a career. Have jobs.” “Jobs?” “Yeah, a career is like having a moving part. You can lose it… like your hair! But a job… If you’re happy, you do a good job, and if you do a good job, you can’t lose it. And one job will lead to another job, and then you’ll have something much more important than a career.” “What’s that, Mr. Matthau?” “A reputation. That’ll get you further. If you’re a good person, if you’re professional, you’ll be someone that people like to work with, just because you’re you. And when they look at the list, maybe they’ll say, ‘I want to work with him, because I know the job’s gonna be good, and it’ll make the day shorter.’”

So I press that upon the younger actors. That, and get to know what’s going on. Get to know the people behind the camera. Get to know the people who make your day possible. They’re all part of the scene. You’ve got to be part of the mix. You’ve got to be conscious of that. You’re just a working stiff and lucky to have a damned job. Anyway, that’s me, talking as somebody born in 1936!

AVC: I don’t think that sort of advice has an expiration date.

HE: Yeah, but I don’t wanna sound like the guy who says, “Get off my lawn!” [Laughs.] But it’s not complicated: be prepared, know your craft, and be part of the team. Simple as that. Oh, and above all, do not take yourself seriously! For me, that’s crime number one. Don’t take yourself seriously, for god’s sake. We’re all in the same deal. As a poet once said, life is a brief pause between two mysteries. I like that. Though I would add, “And don’t be a pain in the ass!”

Being Human (1994)—“Dom Paulo”

HE: Well, of course, that was with Robin Williams. What a terrific guy. What a wonderful man. That broke my heart. When he passed… [Hesitates.] It’s the only time I ever heard Garry Marshall cry on the phone. When I called him… I mean, he was just sobbing. He was just so close, you know. To both of us.

We did that film in Morocco, in North Africa, and to be honest, I wasn’t feeling too well. It was hotter than hell on that beach. It looked like a desolate beach, but what they did, they took two weeks to clean up the beach. There was so much debris! But the people of Morocco, they were wonderful. There’s nothing like working in a foreign country. When you work, you get to know the folks. And if you do a little homework before, that helps a lot. Just some basic historical homework. Know where you are. Know the background. Know the content. But it was quite lovely.

And Robin, of course, was a genius. I’ll never forget one little moment. We were getting wired up, getting our microphones on, the both of us, and when he’d finished—they were still working on me—he told his assistant, “I’ll be back.” And he just started walking. Walking away, toward the ocean, until he became a little speck. I mean, he walked a long way! And then he just stood there, with his hands clasped behind his back, staring at the ocean. Staring, staring, staring. And I noticed this, and I said, “Is Robin okay?” And they said, “He’s okay. He’s just taking it all in. He’s having a private, quiet moment.” That was a very contemplative time for him, a very introspective time. He was a very serious man. And after that, he came back, slowly, and there he was: Robin Williams!

Still waters run deep, and he was a very deep guy. He’s greatly missed. A wonderful human being, very kind and generous, and always ready to extract that wonderful humor that gets you through the day. And when he plugged into that other universe that he could plug into, he was an absolutely extraordinary genius. He and Jonathan Winters? Good lord. [Laughs.]

Fish Police (1992)—“Calamari”

The Book Of Life (2014)—“Carlos Sanchez”

The Lego Batman Movie (2017)—“Jim Gordon”

HE: Hey, I worked with Jonathan Winters, too! We did a wonderful animated series called Fish Police. What a cast we had. My goodness. It was terrific! And I love doing animation. I love microphones. I prefer working in front of a microphone, if I had my choice. You don’t have to wear makeup. [Laughs.] I feel like a shaman when I’m using my voice. No one cares what I look like, no one cares what I’m wearing… you could wear your pajamas! You’re just there, and you conjure. You tell a story. You’re dealing with the content of the story, and the story is everything.

But I loved Fish Police. I mean, working with those people around a microphone… Are you kidding? Jonathan Winters, you could hardly get to work! He’d invent an entire universe around a chair! [Laughs.] Suddenly he’d take off, and you’d know you’d have to stop for 20 minutes, because it was difficult to bring him back down to earth! But, my god, it was just a wonderful experience.

And what other animated projects did I particularly like? There was the one I did for a wonderful Mexican writer/director named Jorge R. Gutierrez called The Book Of Life. I loved that. What a rococo thing that was. There was so much going on on the screen, I said, “I’ve got to see this again!” Highly embroidered. It was lovely honing that character in and shaping it with your voice. I loved that. Oh, and The Lego Batman Movie was fun, because I got to work with Batman! [Laughs.] I just like doing animation. I like it, because I’m a very silly man!

Columbo (1975)—“Hassan Salah”

HE: It occurs to me that one thing I miss is playing bad guys. Every actor, if they can pull it off, loves to play bad guys… and I used to play them. The guy in Pelham 1-2-3, he’s supposed to be a bad guy, right?

AVC: You will be pleased to know, then, that easily the most requested role from readers to ask you about was your episode of Columbo.

HE: [Bursts out laughing.] See? Yeah, there you go! Well, the secret to playing a bad guy… I was aided in this by another wonderful actor, Lee Marvin. We were on our way to camera when we were doing Pocket Money, and I said, “Lee, excuse me, I have to tell you something. I’m usually not a gusher...” And I wasn’t, because by then I was already a veteran actor from the New York stage. But I said, “I gotta tell ya, I just love the way you play bad guys.” And he stopped and he looked at me. And, you know, Lee was tall with a deep voice—he was a Ranger in the Army, by the way, so this guy was a tough fella—and he said [Gruffly.] “I’ve never played a bad guy in my life.” And I said to myself, “Okay, this is another teaching moment!”

He said, “Have you known bad guys?” I said, “Well, yeah, I’m from Harlem, New York. I’ve known a few bad guys!” He said, “Uh-huh. Did they think they were bad guys?” And I thought, and I said, “Not one.” “Uh-huh. No, they thought they had a job to do, that they were victims. They didn’t think they were bad. They were just doing their work. They have a point of view. You can’t play a ‘bad guy’ because then you’re playing a stereotype in a cartoon.” And that helped me in Pelham 1-2-3. I didn’t play him like a bad guy. He had a job to do, that’s all. I had some inner thing that people read into, but that’s up to them.

Oh, and Lee told me something else: he said, “If the camera likes you, that’s something ephemeral. You can be as ugly as the dog’s breakfast, but if the camera likes you… You can be playing bad guys for the rest of your life, but for people to pay the price for a ticket to see you, something has to come through about you that cuts through the bad-guy stereotype.” So after Pretty Woman, I don’t get a chance to play bad guys anymore! [Laughs.] I mean, I love Pretty Woman, of course. I just find that interesting.

AVC: So how was that Columbo experience?

HE: Columbo was terrific! My goodness, Peter Falk, he was working so hard on that show, he was rehearsing between shots by himself in the corner. Here he was, playing this indelible character that he helped create, and you’d’ve thought it was the pilot, he was taking it that seriously. Just the utmost professional. And, of course, he was funnier than hell, and once you touched his funny bone, there was just this gush of laughter! For some reason, we tickled each other. I remember I tickled him by doing this terrible imitation of… Well, I’m dating myself, but it was Jerry Colonna singing. I used to come up behind him singing, “On the road...to...Man-da-lay / Where the old...flo-til-la lay!” And he’d crack up: “Oh, Jesus Christ, it’s Jerry Colonna! What kind of character… What comes out of your brain?” We just had a wonderful time. And, again, I didn’t play that like a bad guy. I had a point of view, I had a job to do. That’s how you play bad guys.

Young Doctors In Love (1982)—“Angelo / Angela Bonafetti”

HE: I did 18 movies with Garry Marshall. That’s something special. But Garry was easy to love. It’s wonderful to be around people who love what they’re doing, you know? And who don’t look backwards too much. He always looked forward. I have a tendency to get steeped in nostalgia. “Ah, the good old days…” Well, if you really investigate them, they weren’t that good. [Laughs.]

AVC: Was Young Doctors In Love the first movie you did with Garry?

HE: Yes! And it was our personal favorite, just because it was a maiden voyage for him. The actors he had… So many of them later became directors and writers. It was such a fertile group of people, and so improvisatory. You didn’t know what the hell was going to go on the next day! It was just a joy. My character, the Mafia guy who dresses up as a woman to disguise himself and be able to protect his father in the hospital, that was all made up on the basketball court. [Laughs.] Little by little, while we were playing half-court basketball.

Garry said, “The way we’re gonna sell this… We’re not going to go into the psychology of why this guy falls in love with a doctor or why the doctor falls in love with him. We’re not gonna go there. That’s a never-mind issue.” And that’s what made it sing. That’s what made it fly. No one ever questioned it! The other characters never questioned it. There was never any soul searching on my character’s part. He never went, “What’s wrong with me? Do I like a man? Do I love him?” No, we just did it!

The Jackie Gleason Show (1969)—“Festival Del Toro ‘Mayor’”

Nothing In Common (1986)—“Charlie Gargas”

AVC: One of your other Garry Marshall collaborations was Nothing In Common, but it wasn’t the first time you’d worked with Jackie Gleason.

HE: I think it was a variety show, sometime in the late ’60s, and it was when I was living in Florida, which is where he filmed it. I was, like, “What the hell is this variety-show business?” But I had to pay my rent, so I said, “Well, I guess I’m doing this job! Guess I’m not doing Chekhov this month!” [Laughs.] Chekhov’s terrific, but it doesn’t pay your rent. So I went off and did it.

That was an experience, seeing that man come in the first day for the table read. We were all waiting for Jackie. “Jackie’s gonna be here!” And we’d already been outlining the show and blocking the show with someone walking through it for Jackie. Of course, Art Carney was there, working away. Art was a terrific guy. Finally, they said, “He’s coming! He’s coming! Line up!” [In a befuddled voice.] “Line up? What is this, the National Guard? What the fuck is this about?” But we lined up.

And in walked Jackie, very tan, with his golf clubs on his shoulder, along with two or three tall, willowy, lovely ladies who looked like they’d just stepped out of a Playboy. It was quite the entourage. And he’s going down the line, “Hey, pal! How are you, pal? How ya doin’, pal?” And he went right through the line and shook everybody’s hand. But he never looked in your eyes. He always looked at your ear or something. “How ya doin’, pal? How are ya, pal?” And I’m just, like, “What the hell?”

Now we’re gonna have the table read. So we sat around—sketch, sketch, sketch—and of course he improvised everything. I said, “Where’s the cue?” [Laughs.] But he was quite wonderful. I’d never been around that kind of celebrity with that kind of adoration. And then we finished, and I said, “Okay, I guess now we’re gonna start rehearsing!” And then he said, “Well, I’ll see you all!” And off he went with the entourage. Again I said, “What the hell? Where’s he going? We’ve gotta rehearse!”

We didn’t see him again for three days. We didn’t see him until we had to do the camera mocking… and when we did, he nailed it. [Laughs.] He had a photographic memory! Me, I can barely remember my social security number, and he’d memorized the damned script! And on top of that, he was ad-libbing, so he had to stay very loose! So it was quite an experience, I must say. It was really something to see.

But Nothing In Common, I think it was his last movie. Garry told me how he convinced him to do it. Because he didn’t want to do it. They were both in Chicago for some reason, and he told Garry, “I don’t wanna do it, pal. That’s it. I just don’t want to do it.” They talked for a long time. And finally Garry says, “[Sighing.] Okay, if you want to be remembered for Smokey And The Bandit Part 3…” and he starts to leave.

That’s when Jackie gets up and yells, “Get back here, you son of a bitch!” He says, “All right, I’ll do it...on one condition: by five o’clock, I’ll give you a signal and let you know if I can keep on going… because at five o’clock, I start drinking!” That’s pretty professional and honest, you know? During the day, he never touched a drop. And usually he gave thumbs-up that he could keep on going a little bit more. But Garry was true to his word: If he put the thumb down, it was, “Stop! Cut! That’s it! No more!”

Of course, that’s also the movie where I said, “This young actor Tom Hanks… Garry, this kid’s good! This kid’s gonna be a star!” And Garry Marshall said, “And he talks fast! That’s what I like: he talks fast. Fast acting is better than slow acting, don’t you know that?” [Laughs.] But, yeah, look at him now. There he is: Mr. Hanks, Mr. All-American. The guy next door. The guy you can trust. I’ve been very fortunate and very lucky to work with the people I’ve worked with.

Pretty Woman (1990)—“Barney Thompson”

Runaway Bride (1999)—“Fisher”

AVC: You mentioned Young Doctors In Love as a sentimental favorite, but do you have any other favorites among your Garry Marshall films?

HE: Oh, they all have aspects that are my favorite. But besides the first one, there’s Pretty Woman, of course, because of its stunning success. I mean, it’s become iconic in and of itself. It’s a benchmark film. People say, “It changed my life!” And it’s a film that I was not interested in, quite frankly, when I saw the premiere. I thought, “Eh, it’s not my kind of movie.” But for some reason, it came by at the right time, touched the right chord, and became this thing that’s bigger than life, and all of a sudden I find out that I’m gonna get a [Golden Globes] nomination. Suddenly I said, “I don’t know if I like this much attention!” I’ve always liked being “the guy.” Being “whatshisname.”

But that movie… It still turns my head. I was so happy for everybody! Richard Gere, I’d already worked with him on American Gigolo, and then we went on to work together again on Runaway Bride, where we worked with Julia [Roberts].

I still remember asking Garry when we were still filming Pretty Woman, “How’s she looking?” [Doing a pitch-perfect Garry Marshall impression.] “The camera loves her! Her life is gonna change, Hector!” [Laughs.] He saw it out front, as soon as the dailies started coming in. That smile… “Bingo! Hello! That’s a million bucks right there!” Plus, she was a serious professional. She didn’t just walk through. She came in, and she did her job. She’s a great citizen. I love her.

American Gigolo (1980)—“Sunday”

HE: Oh, [director Paul] Schrader is... He’s a very deep fellow. A lot going on. A lot of thinking, a lot of introspection. A very quiet man. A very observant man. I didn’t know his profile until years later. I think he had a religious fundamentalist sort of background. But he’s constantly asking questions about the human condition, and he’s just a brilliant writer. I remember that on Gigolo.

I was doing a lot of running then. I was skinny as a rake, and I decided, “That’s it, I’m shaving everything off! I’m not gonna wear any hair on my face. I’m gonna appear just like a cream-faced loon.” And if you see it, there I am, looking like a cream-faced loon. [Laughs.]

Chicago Hope (1994-2000)—“Dr. Philip Watters”

HE: A long-running show, and a very challenging show, because David E. Kelley’s dialogue, his writing, it’s so wonderful. I just loved doing that character… and you had a lot to do! This was a serious doctor show. This was not about which doctors were banging in the cabinet that day. No, this was medicine, and you had to learn that stuff! So it was very challenging.

Of course, we had doctors doing the technical advising, and these guys had more degrees than a thermometer, but they loved hanging around a TV set. They wanted to be extras, walking the halls. I was, like, “You’re an actual doctor, and you want to make believe you’re walking through with your clipboard and a stethoscope around your neck?” “Yeah, yeah, yeah! We love it!” [Laughs.] This otherworldly experience of being on a movie set, they couldn’t get over that. They loved it!

Century City (2004)—“Martin Constable”

AVC: Short-lived though it may have been, Century City was one of those series that really made an impact on those who watched it.

HE: Oh, boy! Well, first of all, Viola Davis… My goodness. I said, “This lady is something!” That was one where I couldn’t stand the location. El Segundo. Oh, my god. With that water plant. They used to say, “El Segundo: From The Sewer To The Sea.” [Laughs.]

But what I really remember about that was working with Viola, of course. And that it was a very, very difficult shoot because I was also doing a movie at the same time. It just happened. The dates collided. They were supposed to be three months apart. But they kept on postponing Garry’s movie—it was Princess Diaries 2—and before you know it… Boom! I said, “Garry! I’m doing this TV show, and now your thing’s gonna start?” So I was schlepping from there to wherever the hell we were doing Princess Diaries and back. That was not a pleasant experience. But, thankfully, everyone cooperated. And I had a good driver. [Laughs.]

Viola Davis, though She was a force. She was serious about her craft. We had lovely conversations, she and I. I’m just so happy for her, man. And the series itself, it was way ahead of the curve. That’s what I liked about it when I first read it. But shooting on that set, with all those mirrors reflecting stuff, took for-bloody-ever, man!