1683: The Siege of Vienna

Kara Mustafa and the Habsburgs

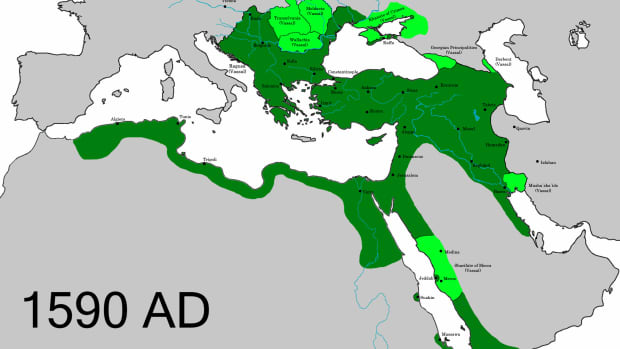

After decades of weakness, internal problems and incompetent leadership, the Ottoman Empire made a comeback in the second half of the 17th century. The new line of Grand Viziers of the competent Koprulu family intended to restore the Ottomans as the strongest state in Europe.

Under the leadership of Koprulu Mehmed and his son Fazil Ahmed Pasha, the Ottomans subdued the rebellious Transylvania, finally ended the conquest of Crete and conquered territories from the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth in modern-day Ukraine.

The only stain on the reputation of the Koprulu Grand Viziers was a defeat suffered against the Habsburgs in 1664. After the Ottoman defeat at the Battle of Saint Gotthard, the Ottomans and the Austrian Habsburgs signed a peace treaty that maintained peace until 1683, though border skirmishes continued as usual between the garrison forts.

When Fazil Ahmed died, he was followed as Grand Vizier of the Ottoman Empire by his brother-in-law, Kara Mustafa Pasha. Fazil Ahmed was seemingly happy enough to maintain the status quo after 1664; Kara Mustafa, on the other hand, was much more ambitious than his predecessor. Under Kara Mustafa’s tenure, border fighting increased, and by 1683, he succeeded in convincing Sultan Mehmed IV that large-scale military operations against the Habsburgs were necessary.

Kara Mustafa assembled a huge army of around 170,000 soldiers and marched against the Habsburgs. It is believed that Kara Mustafa revealed his intentions to assault Vienna only at the last minute, a fact that surprised his subordinates and outraged Sultan Mehmed IV, who left the army after they reached Belgrade and delegated command to his Grand Vizier.

It is also believed that Kara Mustafa’s subordinates expected to only besiege some of the border fortresses of their Habsburg enemies. The Grand Vizier had more ambitious plans, however. After leaving some of his troops to blockade the most important hostile garrisons in the area, the bulk of the Ottoman host pushed towards Vienna.

Despite the great size of the Ottoman host, Kara Mustafa’s subordinates were right to be worried about the plan of the Grand Vizier. Vienna was the capital of the Austrian Habsburgs and, no doubt was a rich city. Still, it was also an important symbol around which the princes of the Holy Roman Empire, who were often hostile towards the Habsburg emperors, could rally.

From a purely military perspective, it was also a very difficult undertaking. Vienna was defended by rivers from two sides, north and east, so the Ottomans’ options for assault were limited. Vienna was also strengthened by using the latest developments in siege warfare. Before the Ottomans could attempt to assault the city’s main walls, they would have to force their way through the city’s outer defenses under the murderous musket and cannon fire of the defenders.

The Siege Begins

The Tatar auxiliaries of the Ottomans arrived first in the area around Vienna and devastated the countryside. Their quick advance also forced the Imperial field army under the command of Charles of Lorraine to retreat, as he feared he was being outflanked.

When it became clear that the Ottomans intended to besiege and capture Vienna, Emperor Leopold, the Imperial Court and a good part of the city's population chose to flee. The field army under the command of Charles of Lorraine also retreated and took up a watchful position west of Vienna.

The command of the city fell to Ernst Rudiger von Starhemberg. The famous military engineer, Georg Rimpler, was also present at Vienna and coordinated the frantic work of the citizens of Vienna to fortify their town further.

Starhemberg had only around 10,000 professional soldiers at hand to defend Vienna, which some 5-6,000 militiamen further reinforced. Additionally, the population of the town was conscripted as the siege progressed. Starhemberg also had around 300 guns to defend the city, though not all were operational.

The main Ottoman force began the siege of Vienna on July 14, 1683. As was expected, the Ottomans attacked the western walls of Vienna. Rimpler was a travelled engineer and was an expert on the methods of the Ottomans. He knew that the Ottomans excelled in destroying enemy walls using mines and made preparations to detect and counter Ottoman mines.

The Ottomans edged slowly closer to the outer defences of Vienna after the siege began. Just as Rimpler expected, mines were detonated around the outer wall quite quickly, but for the time, the defence stood firm. The Ottoman advance was slow, but after a month, the outer defences fell and the defenders were forced to fall back.

Unfortunately for the defenders, Rimpler was gravely wounded during the fighting and died quickly afterwards in early August. The city commander, Starhemberg, was incapacitated for 10 days also when sickness broke out in the city.

Though the progress was slow and costly, the Ottomans were slowly edging closer, and without the arrival of the relief army, it was only a matter of time before they took the city.

Attacking a fort modernised along the bastion lines was a real logistical nightmare and usually cost the attacker huge casualties

The Battle

Emperor Leopold, Charles of Lorraine and the Pope knew this perfectly, and frantic diplomatic negotiations were going on. The Imperial diplomats won over Bavaria, Saxony, Swabia, Franconia and other German states. Venice and Poland-Lithuania also agreed to join the Holy League against the Ottomans.

In August, the allies mobilized their forces and arrived in Austria in early September. The combined Imperial, German and Polish army may have numbered as much as 90,000 men, but only around 74,000 took part in the Battle of Vienna on September 12, 1683.

Lorraine conceded overall command to Jan Sobieski, the King of Poland, but he convinced his allies to follow his battle plan. According to Lorraine’s plan, the allies would attack the Ottomans from the west, coming out of the forest west of Vienna and riding down a hill to face the Ottomans.

Kara Mustafa received reports that a relief army was on its way to save Vienna, so he prepared to face them. He decided to split his army and left a small part to continue the siege. The bulk of the army was deployed at the foot of the hills from where the relief army was expected to arrive.

Kara Mustafa succeeded in guessing the allies’ battle plan, but he failed to sufficiently reinforce his defences to stop their advance when the battle began.

The Imperial force on the allied left and the German princes in the centre pushed back the Ottomans into their camp before they halted their advance to allow the Poles to catch up.

The Poles were not yet in position when the Imperial force attacked without orders. The German princes in the centre joined the assault quickly afterwards. Seeing what was just unfolding, Sobieski did not hesitate and pushed his cavalry down the hill. The momentum of the Winged Hussars and other cavalry units swapped away the Ottoman left, and soon the whole Ottoman army collapsed under the pressure of the relief army.

Before sunset arrived, the battle was over, and the city was saved.

Aftermath

Kara Mustafa tried to find scapegoats for his failure and executed the Pasha of Buda, but his theatrics did not fool sultan Mehme; he knew perfectly well who was the real culprit. He ordered the execution of Kara Mustafa, and before the year was over, the Grand Vizier was dead.

The disaster at Vienna threw the Ottomans in disarray, which allowed the German and Polish troops to push into Hungary and reconquer the Medieval Kingdom of Hungary from the Ottomans. Habsburg’s involvement in the NineYear’s War against France forced them to split their forces between 1688 and 1697, but the Battle of Zenta confirmed the new political reality and forced the Ottomans to accept defeat.

The Treaty of Karlowitz ended the Long Turkish War (1683-1699) and ratified the Habsburg conquest of Hungary, Croatia and Transylvania.

Source

Wheatcroft, Andrew. (2010). The Enemy at the Gate: Habsburgs, Ottomans, and the Battle for Europe. Basic Books.

This content is accurate and true to the best of the author’s knowledge and is not meant to substitute for formal and individualized advice from a qualified professional.

© 2022 Andrew Szekler