Sylvia Plath: Her Life and Importance to American Literature and History

A Name for the Literary Canon

Sylvia Plath's importance in American history is derived from the literary excellence of her writing, and her works show the plight of mid-twentieth-century women. Plath's significance comes from her role as a poet and the ways in which her writing opened the door for the exploration of a feminist martyr to patriarchal society, as well as the treatment of psychiatric patients.

As a post-World War Two confessional poet or a poet who wrote based on a personal attachment to her work, Plath's life can be explored through her poetry and stories. By aligning the works of Sylvia Plath alongside the events in her life, one is better able to understand the poet's importance to American history.

Plath's Early Life

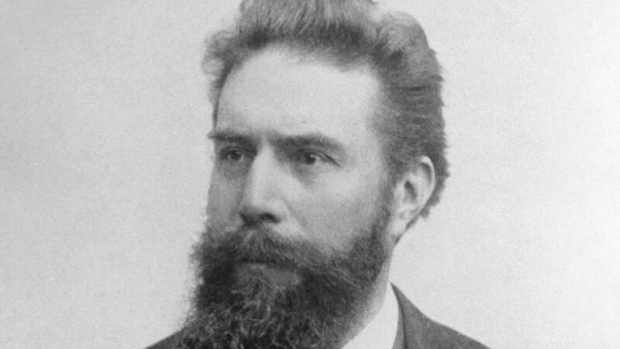

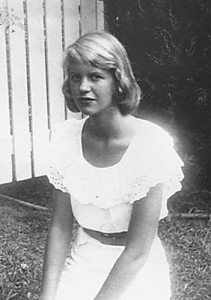

Before the age of eight, Plath led a socially normal life. Born in October of 1932, she grew up in a strongly academic family environment in Winthrop, Massachusetts. Winthrop and the surrounding areas appeared specifically in Plath's poem, "Point Shirley," which represents the town with bleakness. Her father, Otto Plath, was a biology professor, and her mother, Aurelia Plath, was a short-hand teacher.

Plath had her first poem published in The Boston Herald in 1940 when she was only eight, and this would be the beginning of her career as a poet. Also, in November of that year, Plath's father died from surgical complications related to his late-diagnosed diabetes. The poet's paternal struggles appear in many of her poems, such as "The Colossus," "The Beekeeper's Daughter," and "Daddy," where Plath writes, "I have always been scared of you." 1 Plath did not attend the funeral, and the poet only visited Otto Plath's grave once nineteen years after his death.

Plath had her first poem published in The Boston Herald in 1940 when she was only eight, and this would be the beginning of her career as a poet.

A Changing Political and Social Climate

Sylvia's mother, Aurelia Plath, accepted a job at Boston University. They moved inland to Wellesley, Massachusetts. During this period, America entered World War II. The war would have longstanding effects on Sylvia's writing. Plath makes mention of World War II in her later poems; in “The Thin People,” for example, Plath describes scenes from war propaganda of the time, saying that “the thin people” were “only” from “a movie,[…] / Only in a war making evil headlines when we / Were small.”2

Plath played witness to much of the political and media output of the time, particularly the increase of war films that took place in the early nineteen-forties. During this time, Sylvia also entered high school. Plath had works published in her school newspaper and even in magazines such as Seventeen and Christian Science Monitor in 1950, and she began to establish her role as a poet. Plath graduated from high school as valedictorian, and the poet began attending Smith College in Massachusetts on a partial scholarship in the fall.

In the 50s, Smith College was a place where “they were educating women so there would be educated children.”3 Plath attended in the earlier half of the decade, from 1950 to 1955. During this time period, the students of Smith were stuck at an awkward juncture between women having re-entered the labor force and the end of the war when men returned to fill the workforce. Many women opted into working a short period after school, then marrying, settling back into the pre-war role of housewife.

This time in Plath’s life was marked with indecision as the poet was swept up with the changing society, questioning her abilities to work and marry, writing, “would marriage sap my creative energy […] or would I achieve a fuller expression in arts as well as in the creation of children?”4 Sylvia Plath was described as “different” from the typical Smith girl of the time.

Describing her own feelings in comparison to her peers, Plath said she did not plan to fill a “role” or would not change for marriage but would “go on living as an intelligent, mature human being,” mockingly pointing out the wrongful practice of woman’s “vicarious experience” lifestyle in marriage.5

Describing her own feelings in comparison to her peers, Plath said she did not plan to fill a “role” or would not change for marriage but would “go on living as an intelligent, mature human being.”

Where "The Bell Jar" Began: New York and Electroshock Therapy

In the summer of 1953, Sylvia Plath accepted a guest editorship in New York, working for Mademoiselle Magazine, a prize she won with her short story “Sunday at the Minton’s.” Plath would later write her only published novel, The Bell Jar, based on that June of 1953. The book starts with the line, “It was a queer, sultry summer, the summer they electrocuted the Rosenbergs, and I didn’t know what I was doing in New York.”6

The Rosenberg trials and executions had an impact on Plath, as she wrote in her journal that everyone around her seemed complacent and that their lack of reactions was appalling, continuing, “nobody very much thinks about how big a human life is.”7 The Bell Jar plays witness to many of the injustices the young female character, Ethel, experiences and her inability to accept the prescribed role of the time of becoming a submitting housewife.

Upon returning home after New York, Sylvia Plath was informed that she had not been accepted into a Harvard summer course to which she had applied. Later, when Aurelia Plath noticed Sylvia’s legs had healing cuts and questioned her daughter, Plath admitted, "I wanted to see if I had the guts.” Plath was immediately sent to a psychiatrist and was exposed to electroshock therapy for the first of many times. In The Bell Jar, Plath’s feeling about the treatments comes early in the novel, as she writes, “The idea of being electrocuted makes me sick,”8 as the poet reflected on her own experiences vicariously. In the novel, Plath writes, “I thought my bones would break and the sap fly out of me like a split plant,” when the main character, Ethel, is exposed to her first shock treatment.9

Electroshock therapy in the 1950s was more archaic and new. In Plath’s time, doctors didn’t monitor heart rates, used higher voltages, and were excessive in prescribing it for numerous maladies, including depression. Even today, doctors are still unsure of why or how electroshock therapy works. It has become an infrequent practice.

Recommended

Plath's Mental Health Decline

After months of shock treatments, on August 24th, 1953, Sylvia Plath made her first suicide attempt. The event is eerily portrayed in The Bell Jar: “I took the glass of water and the bottle of pills and went down into the cellar”10 and “I unscrewed the bottle of pills and started taking them swiftly, between gulps of water, one by one by one.”11 In a Letter Plath wrote to a friend, Eddie Cohen, after the incident, she writes, “I underwent a rather brief and traumatic experience of badly given shock treatments […] Pretty soon, the only doubt in my mind was the precise time and method of committing suicide.”12 Plath justifies her first suicide attempt with thoughts that she would be locked in a mental hospital for the rest of her life, suffering badly performed shock treatments, and all at the large expense of her family.13

Plath was hospitalized at Mclean Hospital for about six months, where she continued to undergo electroshock therapy. Sylvia returned to Smith for the Spring semester, eventually graduating summa cum laude in 1955. Plath received a Fulbright Scholarship to study in England the next year at Cambridge University. Within her first year in England, Plath met her future husband, Ted Hughes, at a party. The night is infamously remembered: the two drunk and Hughes tried to kiss Plath. Plath eventually bit Hughes’s cheek so hard that “blood was running down his face.”14 Plath almost immediately writes a poem titled “Pursuit,” in which she predicts, “One day I’ll have my death of him.”15

Plath's Marriage to Fellow Poet Ted Hughes and Later Work

By June of 1956, the two poets, Plath and Hughes, were married. Plath returned to Cambridge while Hughes began teaching. The poets moved to the United States in the summer of 1957. They settled in a Boston home, where Plath had a short-lived job teaching at Smith. After one semester, they decided to give up teaching, and both focus on their writing. Plath took a job at a Massachusetts State hospital, where she helped to record the dreams of patients, which eventually led to a book of short stories, Johnny Panic and the Bible of Dreams.

When Plath became pregnant with their first child, Frieda, Hughes decided that he would rather have the child born in England, and so in 1960, the poets moved into a London flat. In October, Plath’s first book of poetry, The Colossus, was published in England to few reviews, though overall success and Plath also turned in her first draft of The Bell Jar. In February of 1961, Plath had a miscarriage with her second pregnancy and wrote a slew of poems, one in particular called “Barren Woman.”

The family soon moved to Devon, and Plath became pregnant in the summer of 1961 with her second child, Nicholas. Over time, Plath became increasingly aware of Hughes’s infidelity. In May of 1962, Plath’s The Colossus was finally published in America to sparse reviews. Plath had begun writing a sequel to The Bell Jar, but when she discovered for sure in July of 1962 that Hughes was cheating on her with Assia Wevill, Plath burned the draft of the book along with hundreds of pages of other works in progress.

Hughes left Sylvia Plath for Wevill in 1962. With two children, an estranged husband, and a new flat in London during the worst winter in a century, 1962-1963, Plath became extremely depressed. All of her later work as a poet, especially Ariel, can be linked through her confessional style to the last few months of her life. The most prevalent theme in the late works of the poet is death, and Plath's most active period of writing began in the last year of her life.

Plath's success was decided by the work produced in her last months of life. Some of the more notable works of this period are “Daddy,” “Lady Lazarus,” and “Ariel.” In October alone, Plath produced more than 25 poems. Lady Lazarus” stands hauntingly in the poet's posthumously published collection, Ariel, stating, “Dying/ Is an art, like everything else./ I do it exceptionally well.”16