Nancy Sinatra‘s music career has been overwhelmed by her classic hit “These Boots Were Made for Walkin'” – even the title of this compilation, Keep Walkin’, references that song. But a deeper dive into Sinatra’s oeuvre shows that the singer had a solid career of hitmaking throughout the 1960s and 1970s, scoring nine top 40 hits between 1965 and 1967, including two number ones, “Boots” and “Something Stupid”, a duet with her dad, Frank. Her sultry good looks and self-possessed singing made her an icon of mod 1960s coolness.

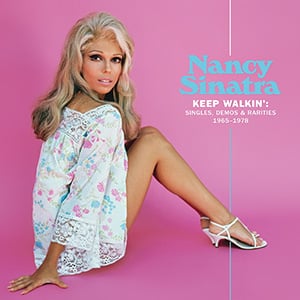

After her run as a hitmaker, Sinatra continued to record and perform, leaning into her camp image and becoming a queer pop icon in the process. In 2004, she returned after a hiatus from recording with a self-titled collection that, in some ways, mirrored the later-day work of her father and Marianne Faithfull. Keep Walkin’: Singles, Demos & Rarities 1965-1978 is yet another compilation that looks to collect her work. However, this set is different – and essential – because it steps away from her chart hits. Keep Walkin’ shows that Sinatra was more than just Frank’s Daughter or the “Boots” singer, and it’s an enjoyable peek into songs that would otherwise be overlooked.

When discussing Nancy Sinatra’s work, one name dominates: Lee Hazlewood. Hazlewood was a prodigiously talented singer-songwriter instrumental in Sinatra’s success, penning her biggest hits. The pair also recorded several albums together, and he helped develop a sound for her. On Keep Walkin’, 12 of the 25 tracks are Hazlewood compositions representing the best of the lot. These songs may not have been the best of the duo’s collaborations, but the tunes reflect that uncanny chemistry between the two performers.

The productions of these tracks are all over the place, as Nancy Sinatra was looking to settle for a sound, so there’s some country, some girl group, some pop. At times, it seems as if Sinatra was groomed as a Dusty Springfield alternate, and at other times, it sounded like Petula Clark inspired her. Sinatra’s voice – though recognizable – wasn’t an overpowering instrument like Barbra Streisand‘s or Aretha Franklin‘s. Like many pop singers, Sinatra didn’t impress with sterling pipes but instead sold her songs with star power and charisma.

There’s also humor in some of these songs. Though the 1960s are remembered as tumultuous, much of their pop culture was silly and ridiculous. It’s why a piece like “The Last of the Secret Agents” works – it’s a blast of horns and surf guitars that sends up on John Barry’s Bond work. (Sinatra herself would record a Bond theme, “You Only Live Twice”.) It perfectly encapsulates Sinatra’s appeal: her slightly flat warbling gives the song’s goofy lyrics a deadpan comedy.

That sense of dry wit makes the songs on Keep Walkin’ more than just simple 1960s pop ditties. If performed sincerely, the previously unreleased “Rockin’ Rock and Roll” would feel puddle-deep. But it’s Sinatra’s droll reading adds some fun finesse, especially at the end when she, the band, and the background singers close the song on a grand finish. On a somewhat plodding story song like “Tony Rome”, Sinatra’s arch singing shakes up the music.

Though a lot of the work in Nancy Sinatra’s discography can feel light and like novelty, Keep Walkin’ shows the point in her salad days when her label reviewed all of its options in how to package their star. “100 Years” is an ambitious number that ties together baroque symphonic pop, country rock, and 1960s pop. The song kicks off with some grand piano playing – almost reminiscent of the chamber of the 1960s. The arrangement also does something interesting to Sinatra’s vocal performance – it’s rare to hear her push herself as a singer, and the fiery, fevered climax of the track just about taxes her range as she nears her breaking point. It’s startling to hear her shake off her ice princess guise to match the song’s intense emotion.

Hazelwood also uses Sinatra’s (perhaps inherited) acting chops on the honky tonk “Shades”, which casts the singer as a heartbroken chanteuse who hides behind a pair of sunglasses to mask her pain. Though the production is dated (the sweetheart chorus takes away from the lyrical pain), the lyrics are pointed and insightful in describing the heartache. The titular shades never manage to hide Sinatra’s hurt. “These shades can hide the tears I cried,” she sings, “but not the way I feel inside.” In describing the futility of hiding one’s pain, she admits, “These shades can only do their part, but the shades can’t hide a broken heart.” The tension that builds with Hazelwood’s sad lyrics, the swinging beat, and Sinatra’s dramatic recitation is never released or relieved. We don’t get a cathartic crescendo; the song fades into resigned silence.

With the Hazelwood compositions, we genuinely see Nancy Sinatra, the legitimate artist and talent. Though their work has been reduced to the kicky “Boots”, the songs they did together reveal a strange and underappreciated performer in the Hollywood child. It’s telling that at her commercial peak in the 1960s, Sinatra largely avoided the trappings of her famous father. Frank Sinatra is rightly considered the greatest interpreter of the Great American Songbook. Nancy’s legacy is far more splintered, as would be expected from the child of an icon. Some would merely write her off as simply riding on her famous father’s coattails, solely able to create a career because of her proximity to him. Others saw her work as timestamped in the 1960s – a bit of pop culture ephemera, alongside beatniks, go-go boots, and lava lamps.

Music in the 1960s reflected a collision of values, generations, and social movements. The rock and roll revolution of the 1950s led to the British Invasion, which saw bands like the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, and the Who muscle out stateside performers for pop chart domination. At the same time, the Civil Rights Movement in the 1960s and racial strife in the country were reflected in pop as Black artists like the Supremes, the Temptations, the Ronettes, and the Four Tops successfully staved off the British Invasion. Second-wave feminism saw the fight for the advancement of women’s rights in the United States.

Amid all this change, pop music was constantly in flux. Bubblegum pop would wrestle with proto-indie rock and soul-pop. Where does an artist like Nancy Sinatra fit into all this swirling unrest? Judging from the breadth of her work, especially with Hazelwood, the answer seemed perplexingly unclear and unanswered.

She didn’t sing songs that reflected the politics of the time, though her image and presence spoke to gender politics. Her role as Hazelwood’s musical partner would bring up questions of agency and autonomy with women in music – was she simply a muse to his Svengali? How much control did she exert over her sound or her career? She alludes to some of this in her interview with Hunter Lea in the liner notes when asked about her thought process behind releasing singles, and she said, “I don’t think it was my decision. It was probably [Lee Hazelwood]; he was the boss of everything.”

Nancy Sinatra flourished as an artist with Hazelwood, so it’s understandable that the material on Keep Walkin’ that isn’t part of their collaboration suffers in comparison. Some of this dip in quality is due to Sinatra recording material that is trendy and far too tied to its time. A song like “Zodiac Blues”, preoccupied with astrological imagery, dates rather badly (despite an engaging, soulful sound). The jaunty “Flowers in the Rain” sounds like a strained attempt at British psychedelic pop.

Though she sounds most at home singing the Hazelwood material, some other songs on Keep Walkin’ show Sinatra as a capable stylist of other writers’ material. Especially good is her sensitive cover of Neil Diamond’s “Glory Road”, which is quite beautiful, her tight range and thin timber adding a poignant sadness and weariness.

The record ends with a shelved duet with Hazelwood, a cover of Cynthia Weil and Barry Mann’s “I Just Can’t Help Believing”, which was made famous by B.J. Thomas and Elvis Presley. Weil and Mann were a songwriting duo from the famed Brill Building, responsible for some of the greatest pop songs of the 1960s. It’s a remarkable piece of work, yet it sounds unfinished. Near the end, both Hazelwood and Sinatra seem to mess up their lines, he more so. It’s a very human moment that rips a bit of the manufactured legend of their union.

The brief moment of mishap at the end of “I Just Can’t Help Believing” is a fitting way to end this compilation. Keep Walkin’ looks to expand on the legend of Nancy Sinatra because so much of her musical legacy is tied up in her mythology as a celebrity or an image. A symbol of the swinging 1960s. The big blond eyes. The boots. The miniskirts. Keep Walkin’ makes the case that underneath all of that superficial window dressing, beat the heart of a genuine talent.