Back in 1958, no other six-stringer sounded anything like Link Wray. Building on the template of his youth-quaking Rumble, Wray went on to record a debut album that remains an unholy classic of raunch’n’roll guitar…

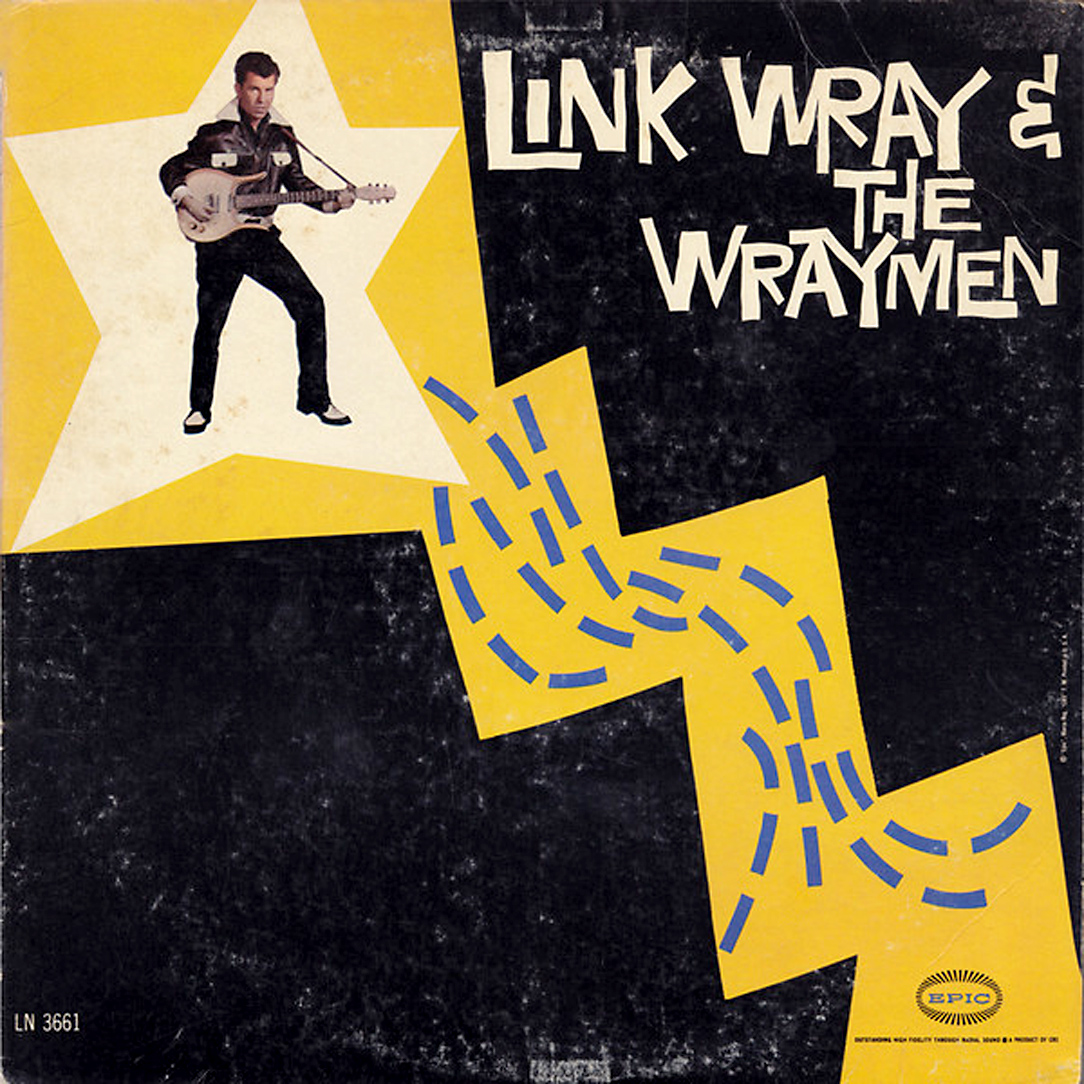

The stance – feet far apart with shoulders hunched, ready for action – anticipating violence or come what may, Link Wray was a man not to be messed with. Dressed all in black except for the white highlights on his collar, pockets, and two-tone shoes, one might expect a switchblade or perhaps the proverbial $2 pistol in his right hand. Instead, an electric guitar was Link’s weapon of choice.

Framed by a white star, highlighted by a zig-zag slash of bright yellow, and set against a stark, black background that snapshot of musical menace filled the upper left hand corner of Link Wray’s 1960 debut album. The record’s eponymous title, “LINK WRAY & THE WRAYMEN”, was scrawled in frenzied white letters, echoing the titles of contemporary cinematic thrillers from Alfred Hitchcock and Otto Preminger, promising tales of crime, menace and suspense. This was clearly not an album of mushy pop songs about teen heartbreak — this was rock’n’roll at its most primal and powerful, dangerous and exciting.

Link Wray was no fresh-faced teen star by the time of his first album’s release. He was already 30, and had spent six years struggling his way up in the music biz – playing all-nighters in rough and rowdy hillbilly bars and honky tonks in both his native North Carolina and around the naval yards surrounding Washington DC. With his two brothers, Vernon and Doug, and bass player, Brantley ‘Shorty’ Horton, they bashed out country tunes and dodged flying beer bottles and fists – gradually making the hillbilly cat leap from twang to rock in the wake of Elvis Presley’s ascension. A bout of tuberculosis left Link with only one lung and doctor’s orders to limit his singing, so the young musician focused on guitar, pushing his sound into dangerous and uncharted territory.

‘Link was no fresh-faced teen star by the time of his first album’s release. He was already 30.’

By 1958, Link was playing louder than almost any other rock’n’roll guitarist as well as discovering the power of distortion – transforming the clean “pling” tone of an electric guitar into the roar of an angry animal. His experiments culminated with punching holes with a pencil in the tweeter speaker of his guitar amp to get the buzzing tone he desired for the instrumental Rumble.

Cut on a one-track recording deck in a Washington DC-area studio for just $57, Rumble was an audio snapshot of barely restrained menace and excitement, like a snarling tiger straining at its chains. Despite the instrumental’s raw power, no label would touch it until the head of Cadence Records, Archie Bleyer, discovered his teenage daughter groovin’ to a copy of the rejected demo. Released in April 1958, the single hit No. 16 on the Billboard Hot 100 despite several radio stations banning it from the airwaves over Chicken Little fears that Link’s rumbling power chords would incite gang fights.

Bleyer hoped to soften Link’s sound for a follow-up release, but Link stood his ground as a member of the loud crowd, and Bleyer dropped him from Cadence in late 1958. Link And The Wraymen cut another powerhouse pair of rockers on Link’s dime — Raw-Hide, along with the yee-haw rockin’ rave-up Dixie-Doodle. By this point Link was producing a sound unlike any other guitarist by moving up from a pencil-pierced speaker cone to wiring his amp through a raucous-generating outdoor speaker horn and combining that Frankenstein with his latest guitar acquisition, a 1958 Danelectro Guitarlin ‘Longhorn’.

‘Released the first week of January 1959, Raw-Hide hit No. 23 on the

Hot 100′

Link began shopping the two new songs to major labels and time and twang were on his side. Shortly after Rumble dropped from the charts, fellow-guitar maestro Duane Eddy scored a Top 10 hit with the instrumental rocker Rebel Rouser. Two more hit singles followed and by December 1958, Eddy’s first LP, Have ‘Twangy’ Guitar Will Travel was headed to record stores and ruled the top of the album chart for months to come.

The sudden rage for guitar-driven instrumentals worked in Link’s favour as Columbia Records subsidiary Epic quickly snapped up Raw-Hide and Dixie-Doodle and signed Link to a three-year contract. Released the first week of January 1959, Raw-Hide hit No. 23 on the Hot 100 during its 13-week run on the charts. The record was popular enough to garner Link And The Wraymen two television appearances, first on the weekday afternoon dance party, American Bandstand, and then a few weeks later on the primetime television show Dick Clark’s Saturday Night Beechnut Show. Both shows featured Link And The Wraymen wowing or terrorising an audience of teen music fans in a sure-fire litmus test, separating the squares from the cool kids.

Hot Sounds For Cool Kids

Looking for a follow-up hit, Epic rushed Link and the band into Columbia’s 30th Street Studio in New York City for a session on 25 February 1959. Although Epic was clearly hoping for hits in the manner of Duane Eddy, it’s interesting to note how the label approached recording sessions at the time. Bob Irwin produced the reissues of Link Wray’s Epic material for the 1992 Sony Legacy CD Walkin’ With Link and the later 2002 release of Slinky! The Epic Sessions ’58-’61 on Sundazed Music. Even though the material was recorded in what was considered one of the top studios of the time, the masters were not always cut with state-of-the-art technology.

“The original masters were a really mixed bag on sound quality,” Irwin says. “Some are very lo-fidelity and others are very high-fidelity. One session would be done on a full-track mono machine, another was done on a two-track machine, and some were done on a three-track machine. There was no rhyme or reason. It’s like whatever machine was available that day was the one they used.”

Working with veteran rock’n’roll, jazz and pop producer Chuck Sagle, Link and his band cut two tough-as-nails instrumentals — the brash and swaggering Radar and the thundering Comanche.

An outtake from the session reveals Sagle’s hipness to the big beat. “All you got, don’t slow it up, for God’s sake keep the feeling all the way through,” Sagle tells the band, before giving special instructions to drummer Doug Wray. “Pound into it… Don’t let down, for God’s sake! The drive is the whole thing with these kids today!”

On 20 March 1959, Link and the band were back in the studio with Sagle for another session, cutting the smokin’ Right Turn and slower mood piece, Lillian, an uncharacteristic slice of sweetness dedicated to and named for the Wray boys’ beloved mother.

With several tracks to choose from, Epic gave the nod to the pounding Comanche and the lovely Lillian for Link’s second Epic single. Released in late May 1959, Epic attempted to give the single extra “umph” with half-page trade ads in Billboard and Cash Box, but it was soon lost in the deluge of Duane Eddy wannabes crowding the release schedules in the summer of 1959.

Even though Link’s second Epic single sputtered, the label was still committed to his career. After a summer spent on the road touring with a variety of rock’n’roll revues, Link and his Wraymen headed back to the Big Apple for more studio time. The goal was to complete enough tracks for their first album. Working again with producer Chuck Sagle, the band spent two days in the studio cutting a variety of instrumentals.

On the first day, 15 September 1959, they cut two Duane Eddy-style twang-fests. Both Caroline and Hand Clapper could have been subtitled ‘Variations On A Theme Of Rebel Rouser’. Both featured big, twangy bass leads and energetic sax solos in the manner of Eddy’s biggest hit. It’s unknown if the obvious Eddy-isms were Epic’s idea or Link’s, but either way both tracks were clearly cut in the hopes of attracting Eddy fans to “follow the Link”.

The sax player stuck around for the next tune, Studio Blues, featuring Link scootin’ back to his own turf with a blues-ified deviation of the Raw-Hide riff. For the final track, the sax player took a hike and Link got down to pure frantic raunch’n’roll excitement with the magnificent Slinky.

The next day the band reconvened with a tune that was Link’s closest brush with polite, sophisticated pop. Rendezvous starts as a politely formal tango, with the delicate plinking of piano ivories reminiscent of a fancy-pants cocktail lounge, until Link’s grungy guitar enters the room like a swaggering no-goodnik, spitting on the floor and flicking spent matches into the bosoms displayed by fancy evening gowns. The result was one of the oddest and most humorous recordings of Link’s career.

The band closed out the sessions by returning to Rumble-town via the barely concealed remake Ramble. It’s a track that is best described as Rumble with the same attitude and sneer but in a slightly nicer neighbourhood.

A little over a month later, Epic paired Slinky with the unusual choice of Rendezvous for Link’s third Epic single. Clothed in a swanky full-colour picture sleeve featuring the Danelectro Longhorn and Link with a big smile on his face, the single was heavily promoted to radio stations. Slinky caught fire in a few markets, including Baltimore and Philadelphia, but fell short of the national chart. Not giving up, Epic soldiered on and Link’s first album hit store racks the last week of January 1960.

Molotov Cocktail

Compiled from the A and B-sides of Link’s three Epic singles along with unreleased tracks from his various 1958-59 sessions, the album was a Molotov cocktail thrown into the pop market of 1960. While it quickly became a holy document for hardcore rock’n’roll fans and n’er-do-well guitar players, it proved too rough and rumbly for popular success.

Link’s remaining two years with Epic Records were a mixed bag. Link and producer Chuck Sagle continued lighting rock’n’roll fires like the 1960 masterpiece of one-lunged vocalising, Ain’t That Lovin’ You Babe backed with Mary Ann. Alongside were terribly wrong-headed attempts to ram Link’s guitar playing into an extremely square hole, like the notorious Mitch Miller-produced single Trail Of The Lonesome Pine which teamed Link with a cornball orchestra from Squaresville.

Link was never able to duplicate the chart success of Raw-Hide during his time at Epic, and when his contract ran out in December 1962, he founded his own short-lived label, Vermillion, before inking a deal with Swan Records to independently produce and record his material for the label. This led to Link’s true ‘Golden Age’, as he released one rock’n’roll riot after another between 1963 and 1967. But the raw, ramblin’ excitement of Link Wray And The Wraymen has remained a classic — accept no substitutes.

Randy Fox

Thanks to Bob Irwin and Jay Millar at Sundazed Music for their assistance with this story.