By means of frequent travel and regular correspondence, many artists, including Akiyama Kuniharu, Ay-O, Ichiyanagi Toshi, Kosugi Takehisa, Kubota Shigeko, Yoko Ono, Saito Takako, Shiomi Mieko, and Tone Yasunao, linked vanguard communities in Tokyo and New York, infusing Fluxus concepts and events with the latest artistic developments from Japan. Most of the literature on Fluxus focuses on the movement’s American and European adherents, barely acknowledging the contributions of Japanese artists. This essay sheds light onto the catalytic role Japanese artists played in this trans-Pacific artistic exchange and aims to expand knowledge not only of Fluxus, but also of the history of the international avant-garde.

Since its beginnings in the early 1960s, Fluxus has attracted artists from a wide range of cultural backgrounds to its open-ended philosophy and practice. It presents a remarkable model of an early transnational artistic movement that drew simultaneously from currents in the United States, Europe, and Japan.1For a brief description of Fluxus, see Michael Corris’s entry in Grove Art Online. Regarding transnationalism and Fluxus, see Hannah Higgins, “Border Crossings: Three Transnationalisms of Fluxus,” in James H. Harding and John Rouse, eds., Not the Other Avant-Garde: The Transnational Foundations of Avant-Garde Performance (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2006), pp. 265–66. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Performance Studies International Conference #13 at New York University in 2007. Another version with a slightly different focus was presented at the NEH Summer Institute on “Re-envisioning American Art History: Asian American Art, Research, and Teaching” at New York University in 2012. It is especially remarkable that Fluxus included so many Japanese artists, including Akiyama Kuniharu, Ay-O, Ichiyanagi Toshi, Kosugi Takehisa, Kubota Shigeko, Yoko Ono, Saito Takako, Shiomi Mieko, and Tone Yasunao. By means of frequent travel and regular correspondence, these artists linked vanguard communities in Tokyo and New York, infusing Fluxus concepts and events with the latest artistic developments from Japan. Most of the literature on Fluxus focuses on the movement’s American and European adherents, barely acknowledging the contributions of Japanese artists.2For example, Grove Art Online’s entry on Fluxus, cited in note 1, hardly mentions the relationship of Fluxus to Japanese avant-garde art. Investigations of this rarely explored history can be found in Alexandra Munroe, Japanese Art after 1945: Scream against the Sky, exh. cat. (New York: Harry N. Abrams in association with the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1994), pp. 218–220; and Midori Yoshimoto, Into Performance: Japanese Women Artists in New York (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2005). By shedding light onto the catalytic role Japanese artists played in this trans-Pacific artistic exchange, this article aims to expand knowledge not only of Fluxus, but also of the history of the international avant-garde.

Building the Tokyo–New York Nexus

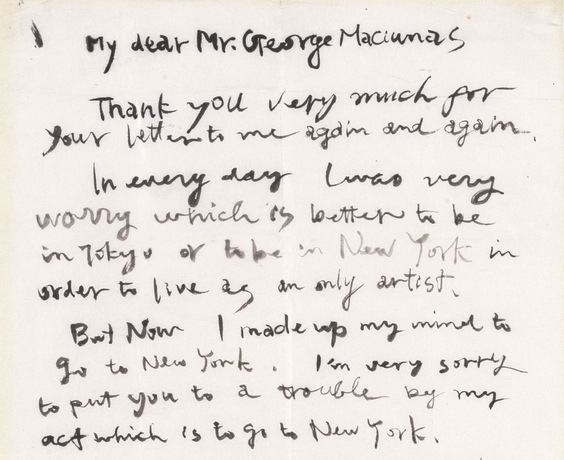

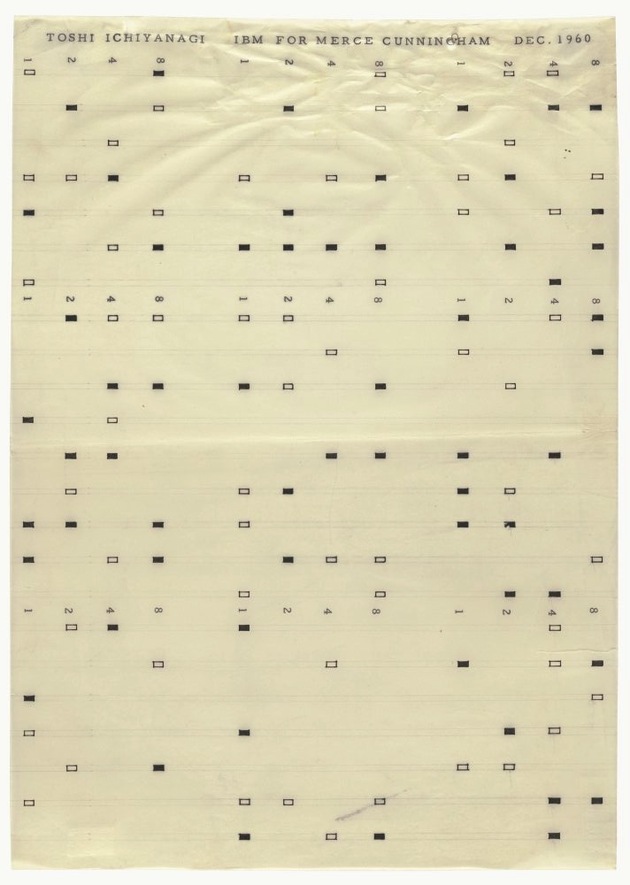

Yoko Ono and composer Ichiyanagi Toshi, married partners from 1956 to 1962, were key figures early on in the forging of ties between artists in New York and Tokyo. In 1958, Ichiyanagi, who had studied at the Juilliard School, attended John Cage’s electronic music composition class at the New School of Social Research, where he befriended future Happenings and Fluxus artists, such as Allan Kaprow, Dick Higgins, and George Brecht. Together with composer La Monte Young, Ono co-organized experimental music, dance, poetry, and art events in her loft on Chambers Street in 1960. These performances inspired the Lithuanian-born artist George Maciunas to stage a similar series of events the following year at his AG Gallery. His intention was to raise money for his prospective publication Fluxus, which was to feature works by experimental artists and composers worldwide. Ichiyanagi and Ono returned to Japan in 1961 and 1962, respectively, and encouraged friends and associates in Tokyo to send music scores, tapes, and texts to Maciunas before Fluxus was officially inaugurated as an artistic movement.3Ichiyanagi sent tapes and scores by fellow Japanese composers to Maciunas in a letter of January 1962. The George Maciunas file, the Jean Brown Archive, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. Prompted by the influx of material, Maciunas planned a special Japanese issue of Fluxus that was to have had contributions by various Japanese artists and writers, including the critic Tono Yoshiaki. He also planned a concert series devoted to works by Japanese composers, such as members of Group Ongaku (Group Music). Neither plan was realized (Fig. 1).4Fluxus no. 3, scheduled to be published in August 1962 but never realized, was provisionally titled “Japanese Yearbox.” See Jon Hendricks, Fluxus Codex (Detroit: Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection/New York: Abrams, 1988), p. 115.

Among the Japanese avant-garde collectives that emerged in the early 1960s, Group Ongaku was the first to make contact with Fluxus. Founded by Kosugi Takehisa and Shiomi Chieko (later known as Shiomi Mieko),5Shiomi Chieko changed her name to Shiomi Mieko around 1967. musicology students at Tokyo National University of Music and Arts, and by Tone Yasunao, who had studied French literature, Group Ongaku used everyday objects—a vacuum cleaner, dishes, an oil can—to create musical improvisations. Although the group had not been exposed to Cage’s music, its members’ knowledge of musique concrète and early twentieth-century avant-garde music led them to explore the concept of objet sonore (sound object, or sound as object).6For more on the group’s formation and its musical lineage, see William Marotti, “Challenge to Music: The Music Group’s Sonic Politics,” in Tomorrow Is the Question: New Directions in Experimental Music Studies (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, forthcoming). See also Shiomi Mieko, Furukusasu towa nanika: Nichijo to ato o musubitsuketa hitobito (What is Fluxus? People who connected everyday life to art) (Tokyo: Film Art, 2005), pp. 61–67. Ichiyanagi attended Group Ongaku’s concert at the Sogetsu Art Center in September 1961 and was astonished to discover a Japanese band that was engaged in something very similar to what he and his peers were experimenting with in New York. That something would soon be called Fluxus.7Tone Yasunao in an interview with the author and Reiko Tomii for the Oral History Archives of Japanese Art, February 4, 2013.

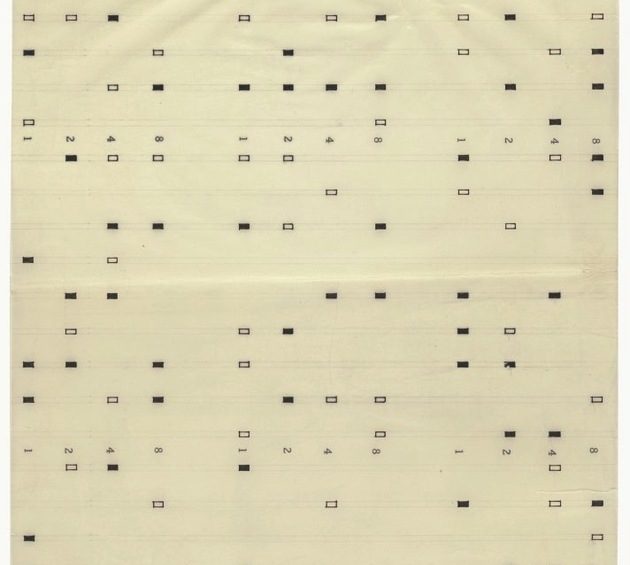

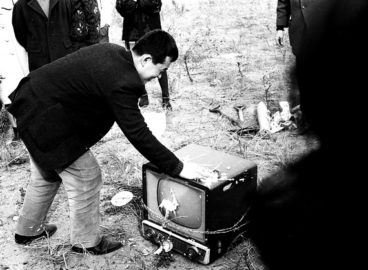

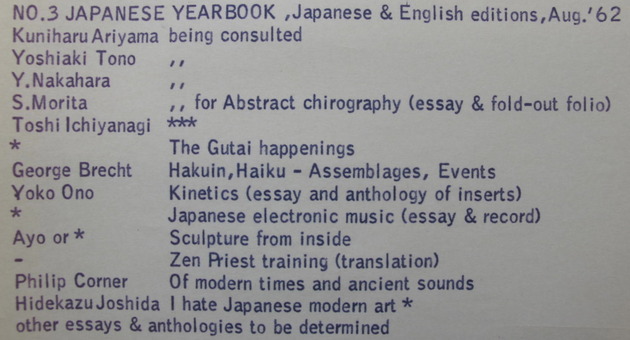

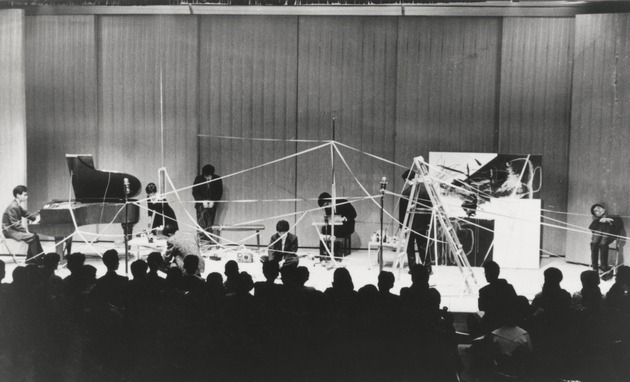

Later that year, Ichiyanagi invited Group Ongaku to perform the Japanese premiere of his IBM—Happening and Musique Concrète, also at the Sogetsu Art Center (Fig. 2). As in his earlier work IBM for Merce Cunningham and Music for Electric Metronome (1960), which was later released as a Fluxus edition, Ichiyanagi used a randomly selected set of IBM computer punch cards as scores, and the performers were allowed to interpret them as they wished (Fig. 3).8Fluxus Editions published multiples of small objects made by Fluxus group members. The multiples were meant to be affordable and widely circulated, and they were often sold as sets. The project was directed by George Maciunas. See here for more on Fluxus Editions. —Editor’s note Instead of playing instruments, Group Ongaku performed a wide range of familiar, unrelated actions from daily life: Shiomi blew soap bubbles; Tone broke a ceramic bowl.9Descriptions of the concert derive from Akiyama Kuniharu, “Gendai ongaku no jiyu to boken” (The Freedom and Adventure of Contemporary Music), Yomiuri Shinbun (December 8, 1961). Their attempt to bring life into art/music matched the direction Maciunas was envisioning for Fluxus, and he would soon become an eager collector of music tapes and scores by Group Ongaku members and their friends.10Tone recalls that Ichiyanagi showed him a letter from Maciunas containing a five- or ten-dollar bill and asking for scores and tapes by Group Ongaku. In response, Tone encouraged friends such as Akasegawa Genpei to send works to Maciunas. Kosugi tells a similar story. See Tone Yasunao and Kosugi Takehisa’s recollections in Emmett Williams and Ann Noel, eds., Mr. Fluxus: A Collective Portrait of George Maciunas, 1931–78 (London: Thames and Hudson, 1997), pp. 130, 134.

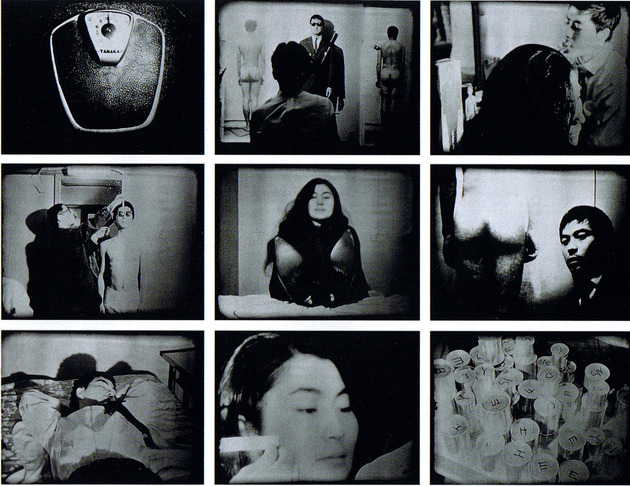

In May 1962, Ono held her own concert at the Sogetsu Art Center (Fig. 4). She enlisted more than thirty avant-garde luminaries to perform her complex pieces, including composers Yuasa Joji and Akiyama Kuniharu, formerly with Jikken Kobo (Experimental Workshop); members of Group Ongaku; the dancer Hijikata Tatsumi; and Akasegawa Genpei, a future member of art collective Hi Red Center. In The Pulse, performers made sounds of their own choosing each time they solved a mathematical problem.11For details of this concert, see Midori Yoshimoto, “Works of Yoko Ono, 1962” in Alexandra Munroe and Jon Hendricks, eds., Yes Yoko Ono (New York: Japan Society and Abrams, 2000), pp. 150–153. Throughout the long evening of unconventional musical events, Ono challenged the traditional one-way relationship between performer and audience. An unidentified reviewer commented: “It is not an art that has already been completed, but an art form that enables the audience to receive something by witnessing the unfolding of nonsense acts, experiencing the process together with the performers.”12“Daitanna kokoromi: Ono Yoko no ivento” (Bold experiment: Yoko Ono’s event), Asahi Journal (June 1962), p. 45. Courtesy Lenono Archive, New York

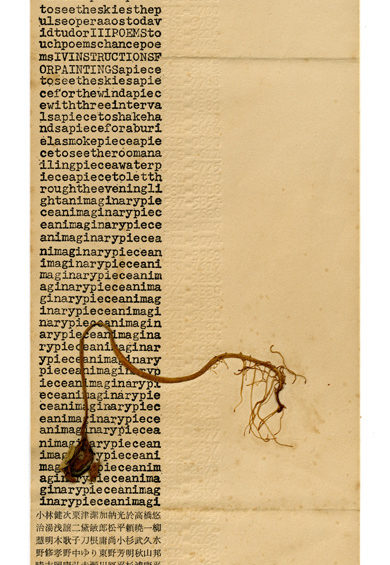

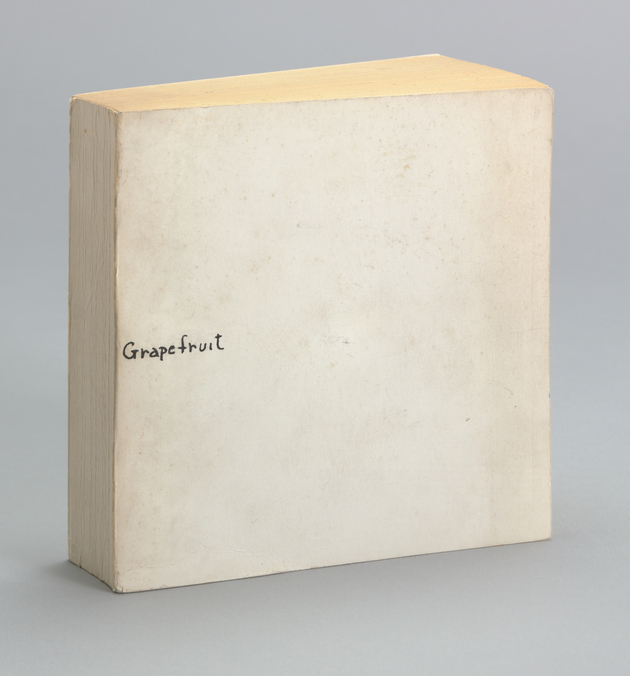

Later that year, Ono participated in John Cage’s concert at the Sogetsu Art Center. The two events—first Ono’s, then Cage’s—incited a Happening craze in Japan. The media described Ono as one of the initiators of Happenings in New York, thus popularizing the term “Happening.” “Event,” the synonymous term used by Fluxus, would be adopted by the artists’ collective Hi Red Center but didn’t catch on as widely with the public.13For example, see “Kemuri no chokoku, moji no nai shishu: Shingeijutsu ‘happuningu’ to torikumu Nihon josei” (Smoke Sculpture, Book of Poems without Letters: A Japanese Woman Undertaking the New Art Form of the “Happening”), Shukan Yomiuri (May 6, 1962). Tone Yasunao encouraged future members of Hi Red Center to adopt the term “Event.” Tone Yasunao interview, February 4, 2013. By the summer of 1964, when she returned to New York, Ono had written a number of conceptual/performative instructions and published them in an anthology entitled Grapefruit (Fig. 5). She had become a renowned figure in Tokyo’s avant-garde circle, having staged a series of exhibitions at Naiqua Gallery, concerts in Kyoto and Tokyo, and having participated in seminal works by her artist friends, including Hi Red Center’s Shelter Plan, held at the Imperial Hotel Tokyo in January 1964 (Fig. 6) and reenacted as Hotel Event by New York Fluxus members in 1965.14According to Tone, Maciunas may have heard about Shelter Plan from another participant, Kubota Shigeko. The artists who put on the very different New York version of the piece may not have known the full details of the original. Tone interview, February 4, 2013.

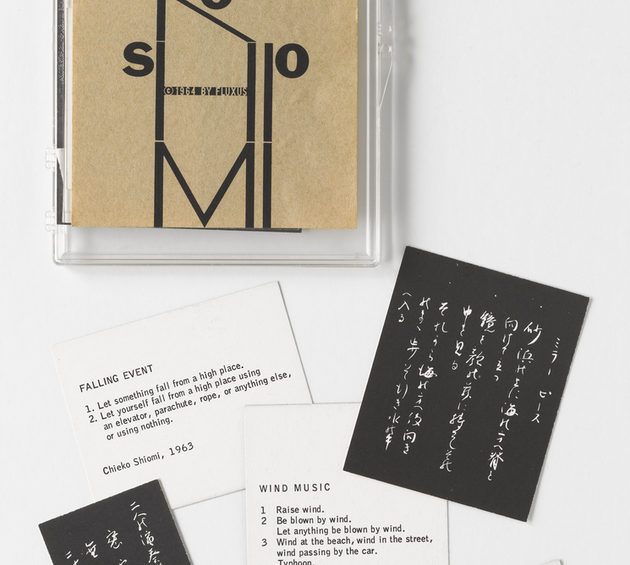

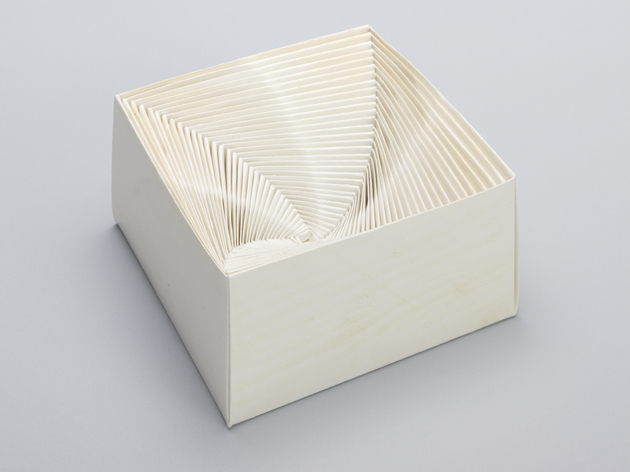

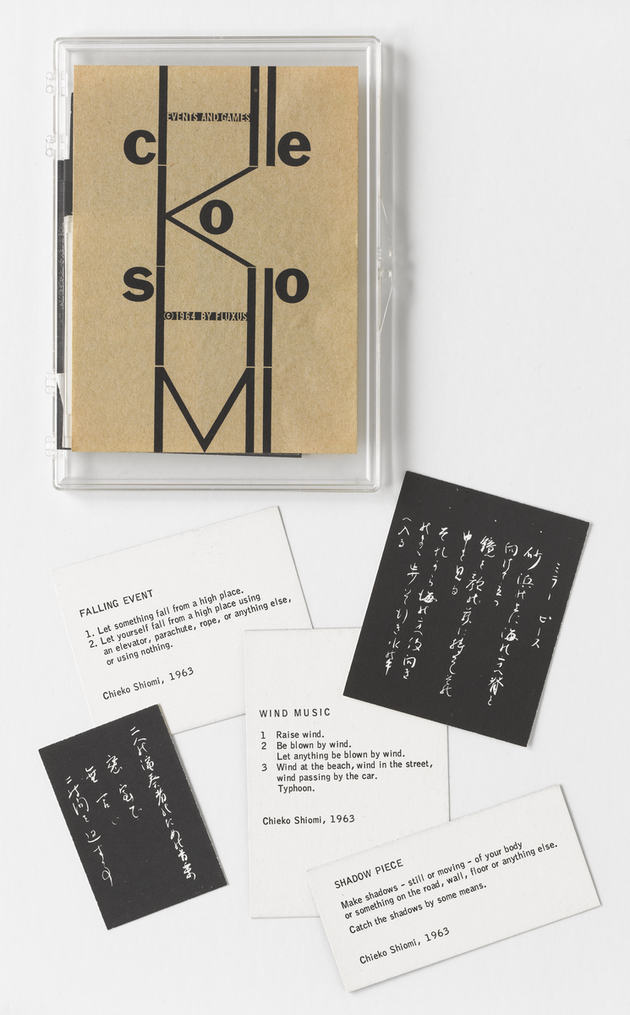

The Korean-born composer Nam June Paik was another important catalyst in linking Tokyo and New York. A graduate of the University of Tokyo, Paik visited the Japanese capital in 1963 on a trip from Germany, where he had made his name by destroying musical instruments in the inaugural Fluxus concerts. During his brief stay, Paik met Tone, Kosugi, and Shiomi of the by then defunct Group Ongaku and asked them to perform in the May 1964 staging of his Events at the Sogetsu Art Center (Fig. 7). He found Shiomi’s Endless Box wonderfully witty and, knowing that would fit Fluxus perfectly, encouraged Shiomi to send it to Maciunas (Fig. 8). A visualization of a musical diminuendo, Endless Box consisted of thirty-four handmade paper boxes that could be nested one inside another.15A diminuendo is a musical term referring to a gradual decrease in the loudness of a sound. Maciunas so much liked the first set he received that he asked for twenty more, and Shiomi used the money he paid for them to travel to New York.16Shiomi, Furukusasu towa nanika, pp.76–77. Sent by post, Shiomi’s Endless Box and several event scores that she included in the package were offered for sale at the Flux Shop six months before the artist herself arrived in New York in July 1964 (Fig. 9).17In a December 26, 1963, letter to Willem de Ridder, who was distributing Fluxus editions in Europe, Maciunas mentioned that he had the “complete works of Shiomi.” See Hendricks, Fluxus Codex, p. 478.

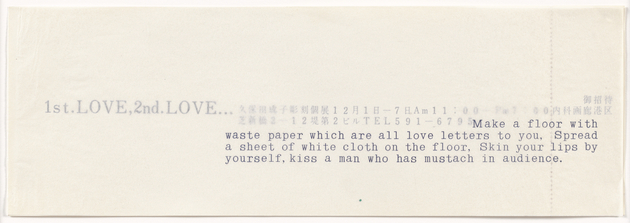

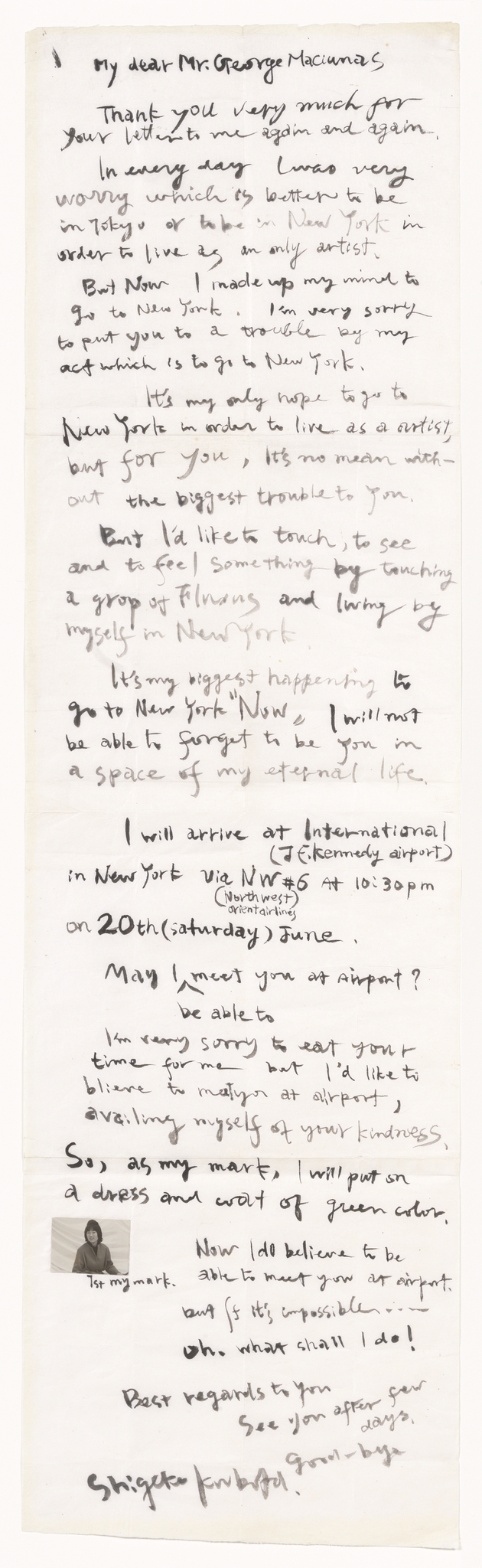

Shiomi’s friend, the sculptor Kubota Shigeko, learned of Fluxus through Ono, Ichiyanagi, and Paik around 1964 and began corresponding with Maciunas. Disappointed by critics’ indifference to the ambitious exhibition of her environmental sculpture 1st.LOVE, 2nd.LOVE… at the Naiqua Gallery (Fig. 10), Kubota decided to accept an invitation from Maciunas to move to New York.18Kubota Shigeko, quoted in Miyata Yūka, “‘Naika datta, garou datta−’ futatabi kaisaimade” (“It was the office of internal medicine and gallery” again: until I held Naiqua Gallery—exhibition of the avant-garde in the 1960s), Aida, no. 80 (August 20, 2002): p. 31. (Fig. 11) In her letter to him, written on a scroll, Kubota expressed her determination: “I’d like to touch, to see and feel something by touching a group of Fluxus and living myself in New York [sic].” Much later, she explained that one of the major factors behind her move was that “Japan [was] so conservative,” made up of “all male artists and male-oriented society.”19Kubota Shigeko, quoted in Jeanine Mellinger and D.J. Bean, “On Art and Artists: Kubota Shigeko,” Profile, no. 3 (1983): p. 21. On July 4, 1964, soon after Japan began issuing tourist visas to facilitate international travel, Kubota and Shiomi took the same flight to New York and received a warm welcome from the Fluxus community. Within a year, they each presented their own Fluxus events and created Flux objects. While Shiomi stayed for only one year, Kubota decided to remain permanently.20For more on Kubota, see Yoshimoto, Into Performance, pp. 169–193; Mary Jane Jacob, ed., Kubota Shigeko Video Sculpture (New York: American Museum of the Moving Image, 1991).

Japanese Contributions to Fluxus

Maciunas’s enthusiasm and admiration for Japanese culture and art were as significant as the change in Japanese foreign policy in strengthening the nascent connection between Japanese and American artists. Not only did Maciunas possess Japanese swords and other artifacts and furnish his apartment with tatami mats, but he led an ascetic lifestyle that gave Japanese artists such as Yoshi Wada the impression that he was a “practitioner of Zen.”21Yoshi Wada, quoted in Mr. Fluxus, p. 134. The artist is also sometimes known as Yoshimasa Wada. Maciunas even dreamed of building an artist’s commune in Japan where residents would grow their own food and spend their time “Fluxing around, publishing all kinds of things, swindling idiots and robbing the fat capitalists.”22George Maciunas, quoted in Mr. Fluxus, p. 128. A committed anti-capitalist and utopian, Maciunas felt a strong connection to the Japanese—and particularly to their group ethics, which were so far removed from Western individualism.23Ibid., p. 133.

Japanese women artists became a hidden force behind the production of Flux objects. Along with Saito Takako, who had joined the group in early 1964, Shiomi and Kubota took part in the Fluxus dinner commune. For several weeks, they shared the duties of shopping for groceries, cooking, and, after dinner, producing Flux objects. Most of the responsibility for the meals fell upon women, and the effort did not last long.24For more on the Fluxus dinner commune, see Shiomi Mieko, Furukusasu towa nanika (What is Fluxus) (Tokyo: Film Art, 2005), pp. 81–82, and “An evening with Fluxus women: a roundtable discussion,” in Midori Yoshimoto, ed., “Women and Fluxus,” a special issue of Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 19, no. 3 (November 2009): pp. 376–377. While Shiomi and Kubota soon found part-time jobs, Saito continued to produce Flux objects until 1967, when she relocated to Europe. Among those works were several versions of Flux Chess, including Sound Chess, Weight Chess, and Nut and Bolt Chess, which she made at the suggestion of Maciunas, a chess aficionado (Fig. 12). Unlike traditional chess sets, Saito’s engaged the five senses. She did not claim authorship but produced the works under the name of the collective.25Saito returned to New York in 1973 initially to help Maciunas build the Flux harpsichord (never used) and to participate in the Flux Game Fest. Since 1979 she has been based in Düsseldorf. For more on Saito, see Yoshimoto, Into Performance, pp. 115–137. Although Fluxus advocated the production of multiples as a way of challenging the traditional sense of authorship, it never sought to undermine the intrinsic value of esthetic quality, which Saito’s crafting skills raised to a high level in Flux objects.

Another Japanese artist, known by the pseudonym Ay-O, had moved to New York from Tokyo in 1958 and joined Fluxus earlier than Shiomi and Kubota did. Although he had hoped to have his first solo show at Maciunas’s AG Gallery, the gallery went bankrupt in 1961, and Maciunas fled to Europe. During Maciunas’s absence, which lasted nearly two years, Ay-O developed friendships with future Fluxus and Happening artists such as Allan Kaprow and Dick Higgins, among many others, helping them with their works and participating in their performances.26Ay-O, Akiyama Kuniharu, Shiomi Mieko, “Roundtable Discussion: Fluxus Universe,” in Art Vivant 11, Fluxus special issue (1983), translated into English by the author. Reprinted in Fluxus – Art into Life (Saitama: Urawa Art Museum, 2004), pp. 102–103. After Maciunas returned to New York, Ay-O helped him build the Flux Shop and Hall on Canal Street, where he lived in a loft just a few doors down. The Flux objects offered for sale at the opening of Fluxus Shop in 1964 included Ay-O’s Finger Box, an edition of cardboard cubes that fit in the palm of the hand and were covered with the artist’s logo, which was designed by Maciunas. The wooden version in the MoMA collection was produced for inclusion in the Fluxkit (Fig. 13). Each box had a hole at the top large enough for a finger to fit through. Inside were objects—or bits of objects—hidden from view, to be examined exclusively by touch. The boxes in the first edition, which comprised about eight hundred, contained only a rubber sponge. The content and quantity were chosen partly to advertise Ay-O’s sponge-filled environment Orange Box, which was installed at the Smolin Gallery. Priced at one dollar and ninety-eight cents, the boxes sold quickly to collectors around the world through the Flux mail order system Maciunas had launched.27Ay-O was gratified when he found one of the boxes in Jasper Johns’s studio a few years later. The boxes were sent by mail, unwrapped, and the hole was covered with a sheet of paper. Ay-O heard that some arrived “non-virgin”; they must have intrigued some postal workers. Ay-O, “Nijino kanatani” (Over the Rainbow), no. 15, Bijutsu Techo (December 1987), translated by the author and reprinted in Over the Rainbow Ay-O Retrospective 1950–2006 (Fukui: Fukui Fine Arts Museum, 2006), p. 168. A later, attaché-case version of Finger Box offered a wider range of tactile sensations. It contained a variety of materials: a small brush, sawdust, Vaseline, and even nothing—a void—to surprise the person interacting with the box. Ay-O’s Finger Box became one of the most popular Fluxus products to explore the previously neglected sensory dimension of touch in artistic experience. The work’s playfulness also corresponded to the Fluxus philosophy of making art accessible to all.

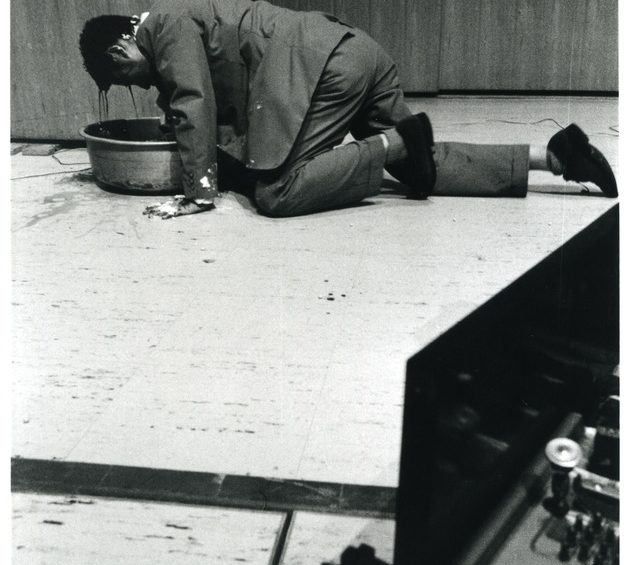

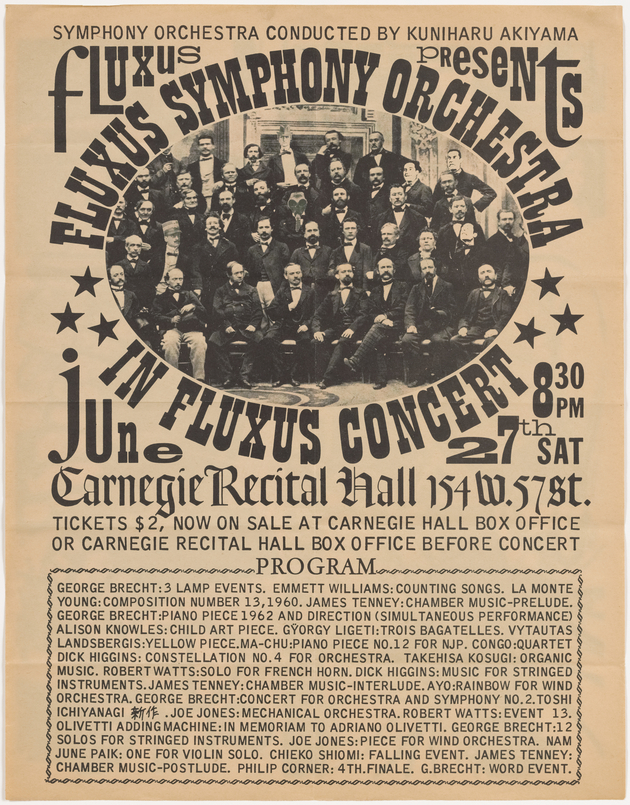

Another Japanese member of Fluxus was the composer and music critic Akiyama Kuniharu, a former member of Jikken Kobo (Experimental Workshop) who had considerable knowledge of Japanese and Western avant-garde art and music. It was he who was responsible for introducing the music of John Cage to Japanese audiences. Akiyama had corresponded with Maciunas from Japan after Ichiyanagi had provided an introduction. He traveled to New York in late 1963, and soon after his arrival, Maciunas showed him how to limit his food budget to five dollars a week, down from the eight dollars per day that he had been spending.28Akiyama recalls that Maciunas was earning approximately nine hundred dollars a month as a graphic designer—that was twice the average income of the day. By spending only five dollars a week on food, he was able to allocate most of his income to the production of Fluxus Events and objects. Akiyama in “Roundtable Discussion: Fluxus Universe,” p. 107. Just as Akiyama was getting ready to leave for Europe around April 1964, Maciunas asked him to conduct the first Flux concert at Carnegie Recital Hall (Fig. 15). Having had no prior conducting experience, Akiyama initially declined, but he gradually gave in to Maciunas’s repeated pleas and stayed in New York for an extra two months.

On June 28, 1964, Akiyama appeared on stage at Carnegie Recital Hall dressed in a tailcoat. He conducted about a dozen of pieces, beginning with The Star-Spangled Banner arranged by La Monte Young.29Ibid., p. 103. Akiyama met La Monte Young in 1959 at the International Summer Course for New Music in Darmstadt, Germany. After seeing Young’s scores, Akiyama suggested that he look up the work of John Cage. Young soon contacted Cage, organized an exhibition of graphic scores in Los Angeles, and subsequently moved to New York. Other pieces included George Brecht’s Solo for Violin, in which all members of the Fluxus Symphony Orchestra polished their instruments when Akiyama gave the signal by polishing his baton; and Kosugi Takehisa’s Organic Music, which called for performers to produce sounds by breathing in and out through paper tubes.30Akiyama knew Kosugi’s piece from its performance the year before at the Sogetsu Art Center. For Akiyama’s account of the Flux concert, see Akiyama Kuniharu, “Kanegi horu ni shikibo o furu” (Conducting at Carnegie Hall), Nihon Tosho Shinbun (August 31 and September 7, 1964), p. 8. Bravely and playfully, and to the audience’s delight, Akiyama even introduced the “Japanese samurai style” of conducting by imitating a sword-fighting movement while leading Dick Higgins’s Constellation II. In preparation for the concert, Akiyama attended the series of Flux Fests held at the Flux Hall and in streets of SoHo on weekend evenings from April to June 1964. Moved by fresh encounters he experienced with Fluxus members in New York, Akiyama became a strong proponent of the group after he returned to Tokyo.31Akiyama contributed articles on Fluxus to publications such as Bijutsu Techo [Art Notebook], including no. 275, a special issue titled From Space to Environment (November 1966), pp. 59–63, 80–88. When Shiomi felt unsure about traveling to New York, Akiyama encouraged her by writing that Fluxus artists loved her work and that she would be welcomed there.

Tokyo Fluxus

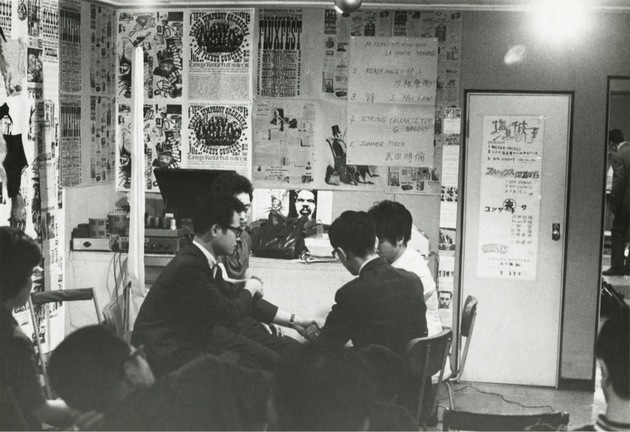

While there was no organized effort to establish a Tokyo branch of Fluxus, a series of Fluxus-related events was held in the Japanese capital after Shiomi’s return in 1965.32Tone reported that in 1963 or ’64, Tony Cox, Yoko Ono’s second husband, spoke about starting a Japanese section of Fluxus because there were many excellent artists and he was collecting their works. Some of the works that Cox collected, however, seem to have been kept by a middle man for some time until they entered the Silverman Collection. Tone Yasunao in an interview with the author and Reiko Tomii, February 4, 2013. Akiyama and Ichiyanagi co-organized Flux Week, which was comprised of a series of events and an exhibition of publications and objects at Gallery Crystal, in September 1965 (Fig. 16). One evening was dedicated to Shiomi’s performance pieces, including Water Music and A Piece for Two Performers. On other evenings, Akiyama, Ichiyanagi, Tone, and composer Takemitsu Toru performed Fluxus works for a small audience (Fig. 17).33For details of Shiomi’s performance, see Yoshimoto, Into Performance, pp. 159–160.

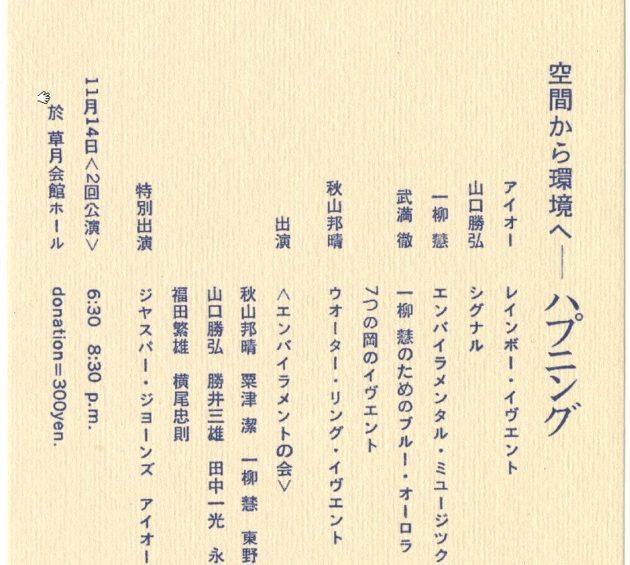

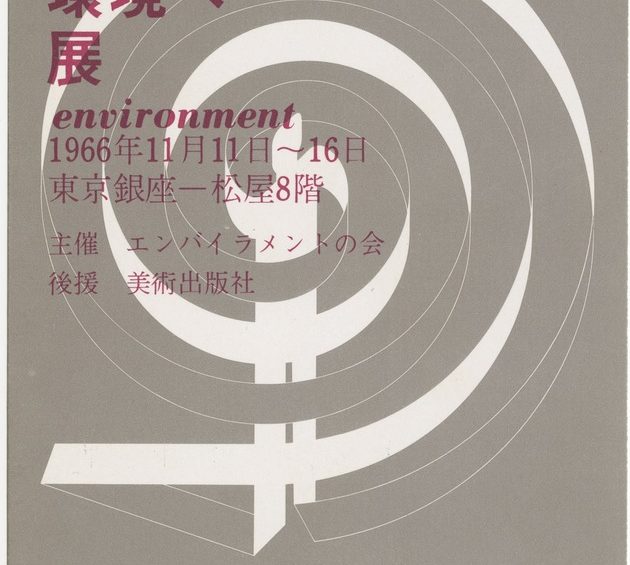

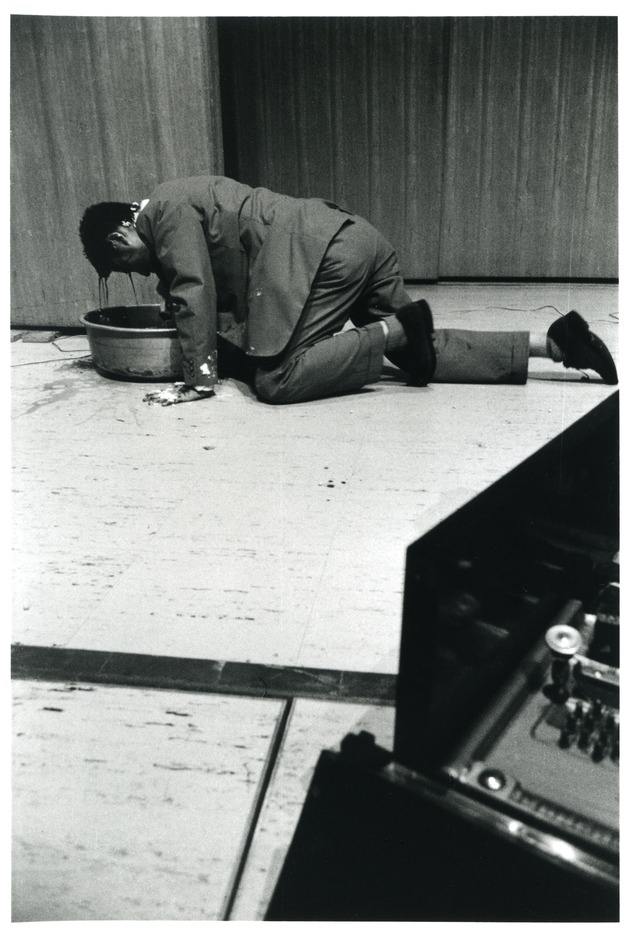

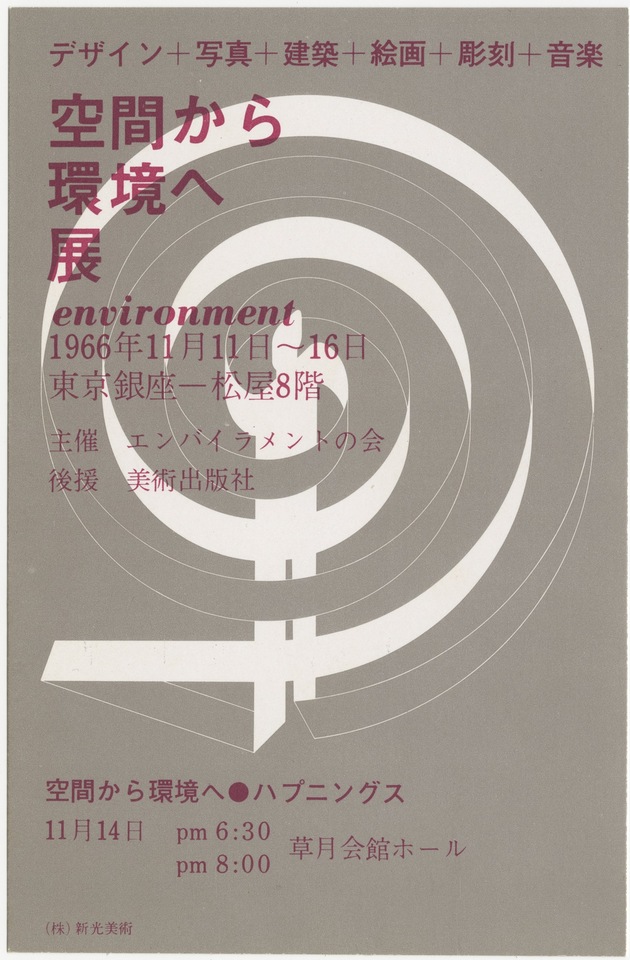

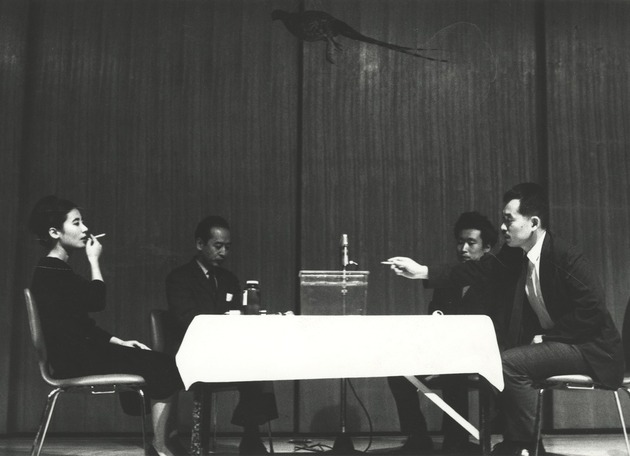

The activities that might be said to encompass “Tokyo Fluxus” culminated with Ay-O’s return to Japan at the end of 1966, after eight years’ absence. A Happening titled Kukan kara kankyo e (From Space to Environment) was presented at the Sogetsu Art Center in conjunction with an exhibition of the same title at the Matsuya Department Store Gallery. A collaborative effort by thirty-eight multidisciplinary artists and critics, the exhibition and performances embodied the new concept of “environment” as a site/catalyst for a “dynamic relationship between humans and their surroundings (Figs. 18a and 18b).”34For more about the exhibition and event, see Midori Yoshimoto, “From Space to Environment: The Origins of Kankyo and the Emergence of Intermedia Art in Japan,” Art Journal 67:3 (Fall 2008), pp. 24–45. For Ichiyanagi’s Environmental Music performance, graphic designers Awazu Kiyoshi and Fukuda Shigeo, Ay-O, and the art critic Tono Yoshiaki sat in a row of chairs on stage and followed the instruction “incline your body on a chair as slowly as possible to an unbearable position” (Fig. 19). Tono interpreted the command by crawling under his chair and lifting it above his head. In his Rainbow Event, Ay-O carried out a series of everyday actions such as brushing his teeth and shaving, to each of which he assigned one of the seven colors of the rainbow, while Shiomi and Akiyama performed simple physical exercises. Shiomi presented Compound View I with Ay-O, Akiyama, and artist Yamaguchi Katsuhiro (Fig. 20).35Although Shiomi’s piece was not listed in the original program, it was performed in the fourth place, after Yamaguchi’s Signal and before Akiyama’s Water Ring Event, according to a note by Nishiyama Teruo, who was in the audience. Comprised of three acts, a series of nonsensical actions unfolded around a water tank placed on a table. Performers took the temperature of the water, sat down, stood up, and wrote a word on a cigarette, which they smoked it until it turned to ashes. Although these performances were dubbed “Happenings” by the press, they were closer to Fluxus Events in their brevity and content, which encouraged the audience to rethink aspects of their daily lives and environments.

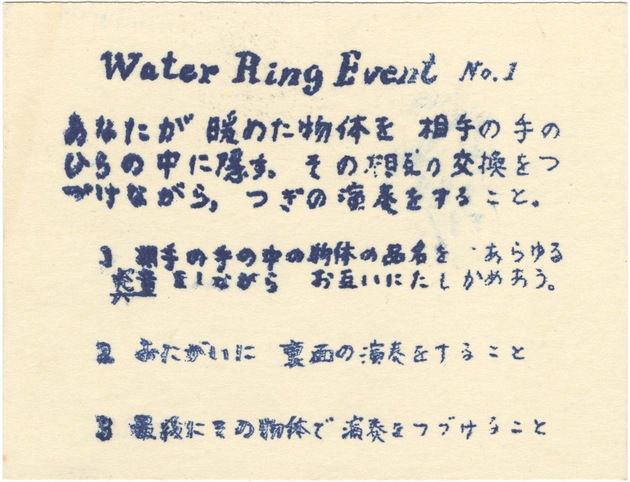

The penultimate piece of the evening was Akiyama’s Water Ring Event No. 1, whose score card was recently rediscovered in the Silverman Fluxus Collection at The Museum of Modern Art (Fig. 21). The Japanese text, mimeographed by Akiyama, provides the following instructions:

Warm an object and hide it in another’s hand. Continue this action of exchange while doing the following:

(1) Pronounce the name of the object in your co-performer’s hand in every possible way as a means of confirmation.

(2) Each performer should perform as instructed on the back of the card.

(3) Finally, continue the performance using the objects.36Translation by Miki Kaneda

While there are a few photographs documenting this Event, the somewhat cryptic descriptions make it difficult to reconstruct the performance. The last work in the program, Takemitsu’s Event for Seven Hills, was dedicated to Ay-O, whose signature motif was the seven colors of the rainbow. On stage, seven performers were stationed at ladders representing seven hills and repeated disparate actions, such as typing “WORD” on a typewriter and performing magic tricks.37This piece was reinterpreted most recently on March 25, 2012, by Ichiyanagi Toshi at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, in the context of Ay-O’s retrospective exhibition Ay-O: Over the Rainbow Once More. It is notable that three former members of Jikken Kobo—Takemitsu, Yamaguchi, and Akiyama—created Fluxus-inspired pieces and presented them on this special occasion, which marked the emergence of intermedia art in Japan.38The most comprehensive publication on Jikken Kobo to date is Jikken Kobo/Experimental Workshop, exh. cat. (Kamakura: The Museum of Modern Art, 2013). It considers individual members’ involvement with Fluxus and intermedia art in the 1960s as an extension of Jikken Kobo, p. 199. This convergence of Fluxus and intermedia art is not surprising, considering the fact that in the mid-1950s Jikken Kobo pioneered cross-genre collaborations that Fluxus would identify as “intermedia” almost a decade later.39It was Yamaguchi who used the term “intermedia” to describe Jikken Kobo’s activities in retrospect. Yamaguchi Katsuhiro, “The Experimental Workshop (Jikken Kobo),” originally written for the exhibition catalogue Shedding Light on Art in Japan–1953 (Tokyo: Meguro Museum of Art, 1996); reprinted in English in Experimental Workshop: Japan 1951–58 (London: Annely Juda Fine Art, 2009), n.p.

In December 1966, Ay-O, with the help of Minami Gallery, organized the Happening for Sightseeing Bus Trip, a piece in which participants rode in a rented bus and performed Fluxus Events at various stops throughout Tokyo (Fig. 22).40For details of the Happening for Sightseeing Bus Trip, see Fluxus–Art into Life (Saitama: Urawa Art Museum, 2004), pp. 92–94; Midori Yoshimoto, “Ay-O’s Environments and Fluxus Events,” Ay-O: Over the Rainbow Once More (Tokyo: the Museum of Contemporary Art, 2012), p. 72; and Hamada Mayumi, “Research Note on Ay-O’s Happening for Sightseeing Bus Trip in Niigata 2012,” Niigatashi bijutsukan kenkyu kiyo (Niigata City Art Museum Bulletin) No. 1 (2012), pp. 14–22. The performers overlapped with those who took part in From Space to Environment, including Shiomi and Akiyama. Together they realized approximately fifteen Events and several Happenings at locations such as the Sengakuji temple and the Meiji shrine. After that, Tokyo Fluxus activities tapered off, but the Fluxus philosophy of turning the viewer into a participant continued to inform the work of many artists. In fact, many artists who had participated in From Space to Environment played an important role in shaping the 1970 Osaka World Exposition as a site for promoting interaction among visitors and the environment.41On Expo ’70, see Midori Yoshimoto, ed. “Expo ’70 and Japanese Art: Dissonant Voices,” Review of Japanese Culture and Society 23 (December 2011).

After 1970, the collective activities of Fluxus waned, but Japanese artists remained actively engaged with the movement. Kubota and Paik, who married in 1965, were close friends with Maciunas and lived in the co-op building that he organized in New York’s SoHo. Ay-O lived in the same building and was a regular participant in most of the late Fluxus Events. In 1972, after corresponding with Maciunas for a decade, Tone moved to New York and joined Fluxus.42Although Tone was skeptical about the continuation of Fluxus in the late 1960s, Paik assured him that the movement was still very much alive. Tone was welcomed as an old friend by Fluxus artists upon his arrival in New York. Tone Yasunao, interview with the author and Reiko Tomii, February 5, 2013. Back in Japan, Shiomi completed nine mail art Events, part of the Spatial Poem series that she originated in New York in 1965 (Fig. 23). For each Event, she mailed instructions to people worldwide, asking them to interpret her instructions and then send her a written report. Through correspondence, she collaborated with Maciunas in designing the objects based on those reports.

After Maciunas’s death in 1978, there was a lull in Fluxus activities, but since the 1990s there has been a resurgence of interest and energy in the movement. Many international Fluxus exhibitions have been providing opportunities for artists’ reunions. Stimulated by these events, Shiomi has reinterpreted Fluxus through multimedia works such as the intermedia event Fluxus Media Opera (1994), which she executed with the help of young musicians and artists.43Regarding Shiomi’s recent activities, see the transcript of her lecture on post: “Intermedia/Transmedia”, translated by the author for post. As artists who were directly involved in New York Fluxus, both Ay-O and Shiomi played a central role in the dissemination of Fluxus in Japan, often by presenting Fluxus Events during their exhibitions or concerts (Fig. 23). Now they are passing the Fluxus spirit on to younger generations.

- 1For a brief description of Fluxus, see Michael Corris’s entry in Grove Art Online. Regarding transnationalism and Fluxus, see Hannah Higgins, “Border Crossings: Three Transnationalisms of Fluxus,” in James H. Harding and John Rouse, eds., Not the Other Avant-Garde: The Transnational Foundations of Avant-Garde Performance (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2006), pp. 265–66. An earlier version of this paper was presented at the Performance Studies International Conference #13 at New York University in 2007. Another version with a slightly different focus was presented at the NEH Summer Institute on “Re-envisioning American Art History: Asian American Art, Research, and Teaching” at New York University in 2012.

- 2For example, Grove Art Online’s entry on Fluxus, cited in note 1, hardly mentions the relationship of Fluxus to Japanese avant-garde art. Investigations of this rarely explored history can be found in Alexandra Munroe, Japanese Art after 1945: Scream against the Sky, exh. cat. (New York: Harry N. Abrams in association with the Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, 1994), pp. 218–220; and Midori Yoshimoto, Into Performance: Japanese Women Artists in New York (New Brunswick, N.J.: Rutgers University Press, 2005).

- 3Ichiyanagi sent tapes and scores by fellow Japanese composers to Maciunas in a letter of January 1962. The George Maciunas file, the Jean Brown Archive, Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles.

- 4Fluxus no. 3, scheduled to be published in August 1962 but never realized, was provisionally titled “Japanese Yearbox.” See Jon Hendricks, Fluxus Codex (Detroit: Gilbert and Lila Silverman Fluxus Collection/New York: Abrams, 1988), p. 115.

- 5Shiomi Chieko changed her name to Shiomi Mieko around 1967.

- 6For more on the group’s formation and its musical lineage, see William Marotti, “Challenge to Music: The Music Group’s Sonic Politics,” in Tomorrow Is the Question: New Directions in Experimental Music Studies (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, forthcoming). See also Shiomi Mieko, Furukusasu towa nanika: Nichijo to ato o musubitsuketa hitobito (What is Fluxus? People who connected everyday life to art) (Tokyo: Film Art, 2005), pp. 61–67.

- 7Tone Yasunao in an interview with the author and Reiko Tomii for the Oral History Archives of Japanese Art, February 4, 2013.

- 8Fluxus Editions published multiples of small objects made by Fluxus group members. The multiples were meant to be affordable and widely circulated, and they were often sold as sets. The project was directed by George Maciunas. See here for more on Fluxus Editions. —Editor’s note

- 9Descriptions of the concert derive from Akiyama Kuniharu, “Gendai ongaku no jiyu to boken” (The Freedom and Adventure of Contemporary Music), Yomiuri Shinbun (December 8, 1961).

- 10Tone recalls that Ichiyanagi showed him a letter from Maciunas containing a five- or ten-dollar bill and asking for scores and tapes by Group Ongaku. In response, Tone encouraged friends such as Akasegawa Genpei to send works to Maciunas. Kosugi tells a similar story. See Tone Yasunao and Kosugi Takehisa’s recollections in Emmett Williams and Ann Noel, eds., Mr. Fluxus: A Collective Portrait of George Maciunas, 1931–78 (London: Thames and Hudson, 1997), pp. 130, 134.

- 11For details of this concert, see Midori Yoshimoto, “Works of Yoko Ono, 1962” in Alexandra Munroe and Jon Hendricks, eds., Yes Yoko Ono (New York: Japan Society and Abrams, 2000), pp. 150–153.

- 12“Daitanna kokoromi: Ono Yoko no ivento” (Bold experiment: Yoko Ono’s event), Asahi Journal (June 1962), p. 45. Courtesy Lenono Archive, New York

- 13For example, see “Kemuri no chokoku, moji no nai shishu: Shingeijutsu ‘happuningu’ to torikumu Nihon josei” (Smoke Sculpture, Book of Poems without Letters: A Japanese Woman Undertaking the New Art Form of the “Happening”), Shukan Yomiuri (May 6, 1962). Tone Yasunao encouraged future members of Hi Red Center to adopt the term “Event.” Tone Yasunao interview, February 4, 2013.

- 14According to Tone, Maciunas may have heard about Shelter Plan from another participant, Kubota Shigeko. The artists who put on the very different New York version of the piece may not have known the full details of the original. Tone interview, February 4, 2013.

- 15A diminuendo is a musical term referring to a gradual decrease in the loudness of a sound.

- 16Shiomi, Furukusasu towa nanika, pp.76–77.

- 17In a December 26, 1963, letter to Willem de Ridder, who was distributing Fluxus editions in Europe, Maciunas mentioned that he had the “complete works of Shiomi.” See Hendricks, Fluxus Codex, p. 478.

- 18Kubota Shigeko, quoted in Miyata Yūka, “‘Naika datta, garou datta−’ futatabi kaisaimade” (“It was the office of internal medicine and gallery” again: until I held Naiqua Gallery—exhibition of the avant-garde in the 1960s), Aida, no. 80 (August 20, 2002): p. 31.

- 19Kubota Shigeko, quoted in Jeanine Mellinger and D.J. Bean, “On Art and Artists: Kubota Shigeko,” Profile, no. 3 (1983): p. 21.

- 20For more on Kubota, see Yoshimoto, Into Performance, pp. 169–193; Mary Jane Jacob, ed., Kubota Shigeko Video Sculpture (New York: American Museum of the Moving Image, 1991).

- 21Yoshi Wada, quoted in Mr. Fluxus, p. 134. The artist is also sometimes known as Yoshimasa Wada.

- 22George Maciunas, quoted in Mr. Fluxus, p. 128.

- 23Ibid., p. 133.

- 24For more on the Fluxus dinner commune, see Shiomi Mieko, Furukusasu towa nanika (What is Fluxus) (Tokyo: Film Art, 2005), pp. 81–82, and “An evening with Fluxus women: a roundtable discussion,” in Midori Yoshimoto, ed., “Women and Fluxus,” a special issue of Women & Performance: A Journal of Feminist Theory 19, no. 3 (November 2009): pp. 376–377.

- 25Saito returned to New York in 1973 initially to help Maciunas build the Flux harpsichord (never used) and to participate in the Flux Game Fest. Since 1979 she has been based in Düsseldorf. For more on Saito, see Yoshimoto, Into Performance, pp. 115–137.

- 26Ay-O, Akiyama Kuniharu, Shiomi Mieko, “Roundtable Discussion: Fluxus Universe,” in Art Vivant 11, Fluxus special issue (1983), translated into English by the author. Reprinted in Fluxus – Art into Life (Saitama: Urawa Art Museum, 2004), pp. 102–103.

- 27Ay-O was gratified when he found one of the boxes in Jasper Johns’s studio a few years later. The boxes were sent by mail, unwrapped, and the hole was covered with a sheet of paper. Ay-O heard that some arrived “non-virgin”; they must have intrigued some postal workers. Ay-O, “Nijino kanatani” (Over the Rainbow), no. 15, Bijutsu Techo (December 1987), translated by the author and reprinted in Over the Rainbow Ay-O Retrospective 1950–2006 (Fukui: Fukui Fine Arts Museum, 2006), p. 168.

- 28Akiyama recalls that Maciunas was earning approximately nine hundred dollars a month as a graphic designer—that was twice the average income of the day. By spending only five dollars a week on food, he was able to allocate most of his income to the production of Fluxus Events and objects. Akiyama in “Roundtable Discussion: Fluxus Universe,” p. 107.

- 29Ibid., p. 103. Akiyama met La Monte Young in 1959 at the International Summer Course for New Music in Darmstadt, Germany. After seeing Young’s scores, Akiyama suggested that he look up the work of John Cage. Young soon contacted Cage, organized an exhibition of graphic scores in Los Angeles, and subsequently moved to New York.

- 30Akiyama knew Kosugi’s piece from its performance the year before at the Sogetsu Art Center. For Akiyama’s account of the Flux concert, see Akiyama Kuniharu, “Kanegi horu ni shikibo o furu” (Conducting at Carnegie Hall), Nihon Tosho Shinbun (August 31 and September 7, 1964), p. 8.

- 31Akiyama contributed articles on Fluxus to publications such as Bijutsu Techo [Art Notebook], including no. 275, a special issue titled From Space to Environment (November 1966), pp. 59–63, 80–88.

- 32Tone reported that in 1963 or ’64, Tony Cox, Yoko Ono’s second husband, spoke about starting a Japanese section of Fluxus because there were many excellent artists and he was collecting their works. Some of the works that Cox collected, however, seem to have been kept by a middle man for some time until they entered the Silverman Collection. Tone Yasunao in an interview with the author and Reiko Tomii, February 4, 2013.

- 33For details of Shiomi’s performance, see Yoshimoto, Into Performance, pp. 159–160.

- 34For more about the exhibition and event, see Midori Yoshimoto, “From Space to Environment: The Origins of Kankyo and the Emergence of Intermedia Art in Japan,” Art Journal 67:3 (Fall 2008), pp. 24–45.

- 35Although Shiomi’s piece was not listed in the original program, it was performed in the fourth place, after Yamaguchi’s Signal and before Akiyama’s Water Ring Event, according to a note by Nishiyama Teruo, who was in the audience.

- 36Translation by Miki Kaneda

- 37This piece was reinterpreted most recently on March 25, 2012, by Ichiyanagi Toshi at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Tokyo, in the context of Ay-O’s retrospective exhibition Ay-O: Over the Rainbow Once More.

- 38The most comprehensive publication on Jikken Kobo to date is Jikken Kobo/Experimental Workshop, exh. cat. (Kamakura: The Museum of Modern Art, 2013). It considers individual members’ involvement with Fluxus and intermedia art in the 1960s as an extension of Jikken Kobo, p. 199.

- 39It was Yamaguchi who used the term “intermedia” to describe Jikken Kobo’s activities in retrospect. Yamaguchi Katsuhiro, “The Experimental Workshop (Jikken Kobo),” originally written for the exhibition catalogue Shedding Light on Art in Japan–1953 (Tokyo: Meguro Museum of Art, 1996); reprinted in English in Experimental Workshop: Japan 1951–58 (London: Annely Juda Fine Art, 2009), n.p.

- 40For details of the Happening for Sightseeing Bus Trip, see Fluxus–Art into Life (Saitama: Urawa Art Museum, 2004), pp. 92–94; Midori Yoshimoto, “Ay-O’s Environments and Fluxus Events,” Ay-O: Over the Rainbow Once More (Tokyo: the Museum of Contemporary Art, 2012), p. 72; and Hamada Mayumi, “Research Note on Ay-O’s Happening for Sightseeing Bus Trip in Niigata 2012,” Niigatashi bijutsukan kenkyu kiyo (Niigata City Art Museum Bulletin) No. 1 (2012), pp. 14–22.

- 41On Expo ’70, see Midori Yoshimoto, ed. “Expo ’70 and Japanese Art: Dissonant Voices,” Review of Japanese Culture and Society 23 (December 2011).

- 42Although Tone was skeptical about the continuation of Fluxus in the late 1960s, Paik assured him that the movement was still very much alive. Tone was welcomed as an old friend by Fluxus artists upon his arrival in New York. Tone Yasunao, interview with the author and Reiko Tomii, February 5, 2013.

- 43Regarding Shiomi’s recent activities, see the transcript of her lecture on post: “Intermedia/Transmedia”, translated by the author for post.