Slate has relationships with various online retailers. If you buy something through our links, Slate may earn an affiliate commission. We update links when possible, but note that deals can expire and all prices are subject to change. All prices were up to date at the time of publication.

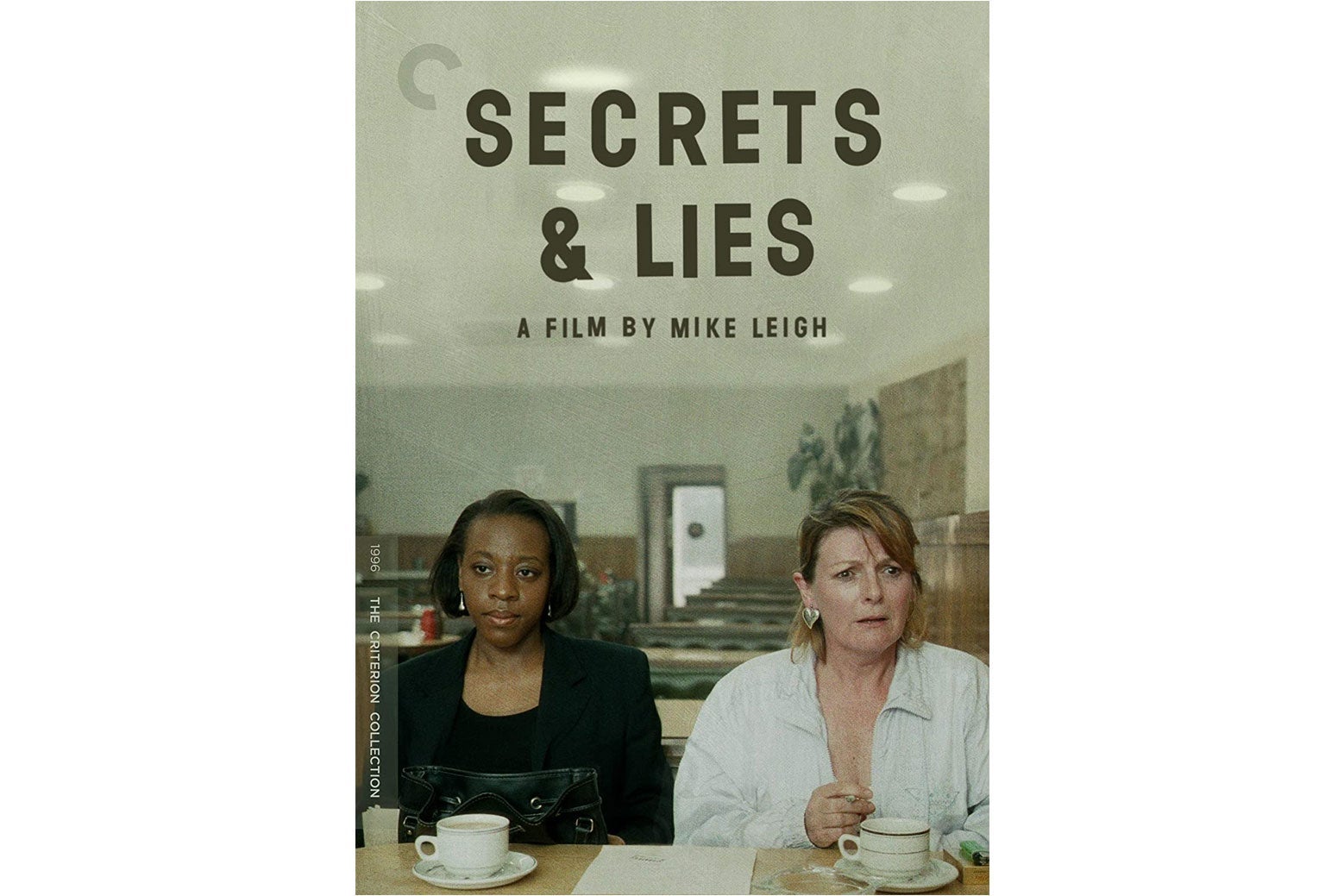

Twenty-five years ago, Mike Leigh’s Secrets and Lies stormed the film world, winning the Palme d’Or at Cannes and later getting nominated for five Oscars including Best Picture. The film portrays a dysfunctional East London extended family whose lives are upturned when middle-aged Cynthia (Brenda Blethyn) meets the daughter she gave up for adoption decades before, Hortense (Marianne Jean-Baptiste). Out this week on DVD and Blu-Ray as part of the Criterion Collection, Secrets and Lies is still a master class in character acting, full of richly imagined performances not only by its two Oscar-nominated stars but also by Timothy Spall, Phyllis Logan, and Claire Rushbrook. Developed, like all of Leigh’s films, through months of painstaking improvisation and character creation, it’s a compelling, economically told story full of surprising reveals and memorable moments.

I spoke to Mike Leigh about keeping secrets from your actors, why Blethyn looks so surprised in the film’s most famous scene, and his post-Oscars encounter with Harvey Weinstein. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Slate: For years, your movies were synonymous with a certain kind of working-class white Londoner. Secrets and Lies opens with Hortense’s mother’s funeral and a sea of Black faces. That’s a community we hadn’t previously seen in a Mike Leigh movie. Were you making a deliberate statement with that choice?

Mike Leigh: Well, yes, I suppose so. That hymn that they sing at the funeral is the classic hymn that West Indian families sing at funerals in the U.K. So that was very much all about that. But I think that’s a very marginal consideration because the bottom line is that’s what the film’s about.

Your collaborative rehearsal process gives your actors a tremendous amount of agency in the creation of their characters. What did Marianne Jean-Baptiste bring to Hortense and to your process?

Well, it’s what you see. The original motivation for the film was that people close to me in my own family adopted kids because they couldn’t have kids. So I decided to make a film about adoption. And once I started to research it, I discovered that in the 1960s in the U.K., a lot of white girls gave away mixed-race babies. And once I got that idea on the go, I was gagging to get Marianne in it. And to answer your question, she brought to it an enormous depth and compassion and wit and imagination. In a very important scene in the film, where she’s in her apartment with a friend, a Black girlfriend, played by Michele Austin—that’s a key scene because that’s the only time you get to see more of her personality and more of her behind her reserve.

She’s able to let her guard down, being alongside a close friend, a Black friend, as opposed to the mostly white environments that she’s in in the rest of the movie.

Absolutely.

The scene that I think sticks in most people’s memories is the café scene between Hortense and Cynthia, when Cynthia suddenly remembers how it was she could have had a Black daughter. You present that scene in one long two-shot so that it feels almost like a short play. Why’d you make that choice?

Well, the truth is that we did go in on close-ups when we shot it. But when we got to that scene in the cutting room, it did feel as though it could work as a single 8½-minute uninterrupted piece of action. Quite a bit happens in that scene! The bottom line is you can only do that sort of thing with that quality of character actors. Like all the action in the film, we began by improvising, and then scripting it through rehearsal. And we got it very, very precise, and then they ran it and ran it and ran it so that they were really on top of it.

That precision is a real hallmark of your method. When I was a college student, I really idolized the Mike Leigh method. I even, one summer, tried to direct my own Mike Leigh–style theater project. I spent a summer with actors creating characters, and then we would put them in scenes together, and it was extremely difficult. We ended up with this enormous mess of improvisation that just went absolutely nowhere. It was basically the exact opposite of a Mike Leigh script. When you’re going through this process with your actors, do you find it exhausting, or is it exciting every time to be discovering these new things with these performers?

Well, it’s exciting every time because that’s what it’s about. However, it is also exhausting. You work your balls off, really. There’s no way around that. And look, ours is not the task to analyze your production.

Thank you.

It’s about being tough about “No, let’s fix it,” and “Let’s get it right,” and “Let’s refine it and polish it.” There’s very, very little improvisation on camera in my films.

A line I really loved in the film was Monica saying, “You can’t miss what you’ve never had,” and Maurice asking, “Can’t you?” They’re talking about the child they’ve never had, of course, but it made me think about how all of these characters are missing things that they’ve never had. The whole film is constructed around missing people and untold stories. How do you make a film about all of these absences and vanishings and still make the story move along, still compel us to want to know what’s happening next?

Well, by the nature of how I make and construct these films, it’s about creating a completely three-dimensional world that actually lives over the months of preparation and through the shoot in a very three-dimensional way. So if you do that, it’s all there. It’s all implicitly there.

The character creation is about helping the audience understand that there’s all kinds of stuff we’ll never know about—but that is still there in the characters.

One of the questions that people ask about the film is, “Why doesn’t Cynthia tell Hortense who her father is?” Now, during the months of preparation, a lot of it’s done through improvising, but a lot of it’s done by just talking into existence the backstory. Because obviously you can’t actually go back and improvise everything. So I was working with Brenda, and we were dealing with about the time Cynthia was about 16. Very vulnerable, very susceptible, very prone to getting drunk. And somewhere along the line, because I knew what tricks I was up to, and I was developing this character with Marianne, I suggested that at a particular party, she was pretty drunk, and she went into a bathroom with a Black guy, had a fuck, and that was it.

The interesting thing is that not only Cynthia but Brenda Blethyn forgot that. So when we, further down the line, reached the point in question to explore through improvisation Hortense getting in touch with Cynthia—this is during the rehearsal period, quite a long time before we shot anything—we arranged a telephone call with Marianne on a phone away somewhere. Called her up, and it was the prototype of that scene. And, very reluctantly, after a couple of calls, Cynthia, as in Brenda, agreed to meet this person.

At the beginning of these projects, on Day 1, everyone that’s going to be in it gets together and just says hello, and has a drink, and that’s that. And then everybody who’s in it, in my films, doesn’t know anything about anything that the character wouldn’t know. So they never see anybody again. Now, somewhere in her head, Brenda thought the person she’d heard on the phone, the actor playing her daughter, was in fact Emma Amos, who plays a different role in the film. And she was standing there in character in the real street. I was way on the other side of the road clocking it from a distance. And she suddenly gets approached by this Black woman. And Brenda, the bit of her that’s Brenda, thought: “This is a damn nuisance. I’m in the middle of an improvisation. I don’t want to talk to this woman. [With dawning realization] And how does she know my character’s name?”

We reconstructed that properly in the scene outside the underground station where they meet. And then she says, “Well, I can’t be your mother.” And then, ding, she suddenly remembers something. Now, of course, it was completely organic, because actually, in the first place, Brenda hadn’t remembered it either, you see. That’s a real, organic, hidden thing, and I know, and she knew, and now you know that actually it’s because, apart from anything else, the embarrassing part of it for Cynthia—and incidentally for Brenda—is she didn’t remember that she’d had a fuck with a Black guy.

Secrets and Lies was an enormous success. It won the Palme d’Or, it was one of the Best Picture nominees in the year that indie movies seemed to take over the Oscars. Do you have memories of that year, when you were constantly going to events with the Coens and Anthony Minghella? Was that exciting, or was it a drag?

One would have to be a seriously bad curmudgeon to think it was a drag, really. It was great! It was a gas! First of all, we won the Palme d’Or, which was fantastic. You know, you don’t win the Palme d’Or. And, yeah, the Oscars was a funny old experience. The English Patient walked away with all the awards, and the following year, my producer Simon Channing Williams and I rather cautiously went to see Harvey Weinstein with a possibility of him being involved with Topsy-Turvy—which, thank God he wasn’t—and he entertained us in his dressing gown in his hotel room in the Savoy Hotel in London, and he said, “I could have got you those Oscars.”

I’m dying imagining the Miramax version of Topsy-Turvy. It would have been an hour and 25 minutes long.

Well, it was a very complicated shoot, and we made it on something of a shoestring. We were constantly changing the schedule. And nearly every day, Simon would come out at lunchtime, and we’d have a chat, and we’d say, “Thank God Harvey never got involved in this.” He’d have fucked it up from A to zed.

At one point, you were scheduled to shoot a film in the summer of 2020. What’s the state of that project now?

It’s on hold. People are shooting stuff, and they’re shooting under heavy-duty COVID protocols and procedures. And it’s in the nature of what I do that, social distancing and all the rest of it, I can’t make a film that way. So at the moment, it’s on hold, probably until next year, which will be two years late. If I’m still with you—I was 78 recently. But it’ll happen. I can’t tell you anything about it, obviously.

Let me know if you need an assistant who’s got experience making a totally terrible version of a Mike Leigh project.

That’s just what I need.