Florence Stoker, the woman who copyrighted Dracula

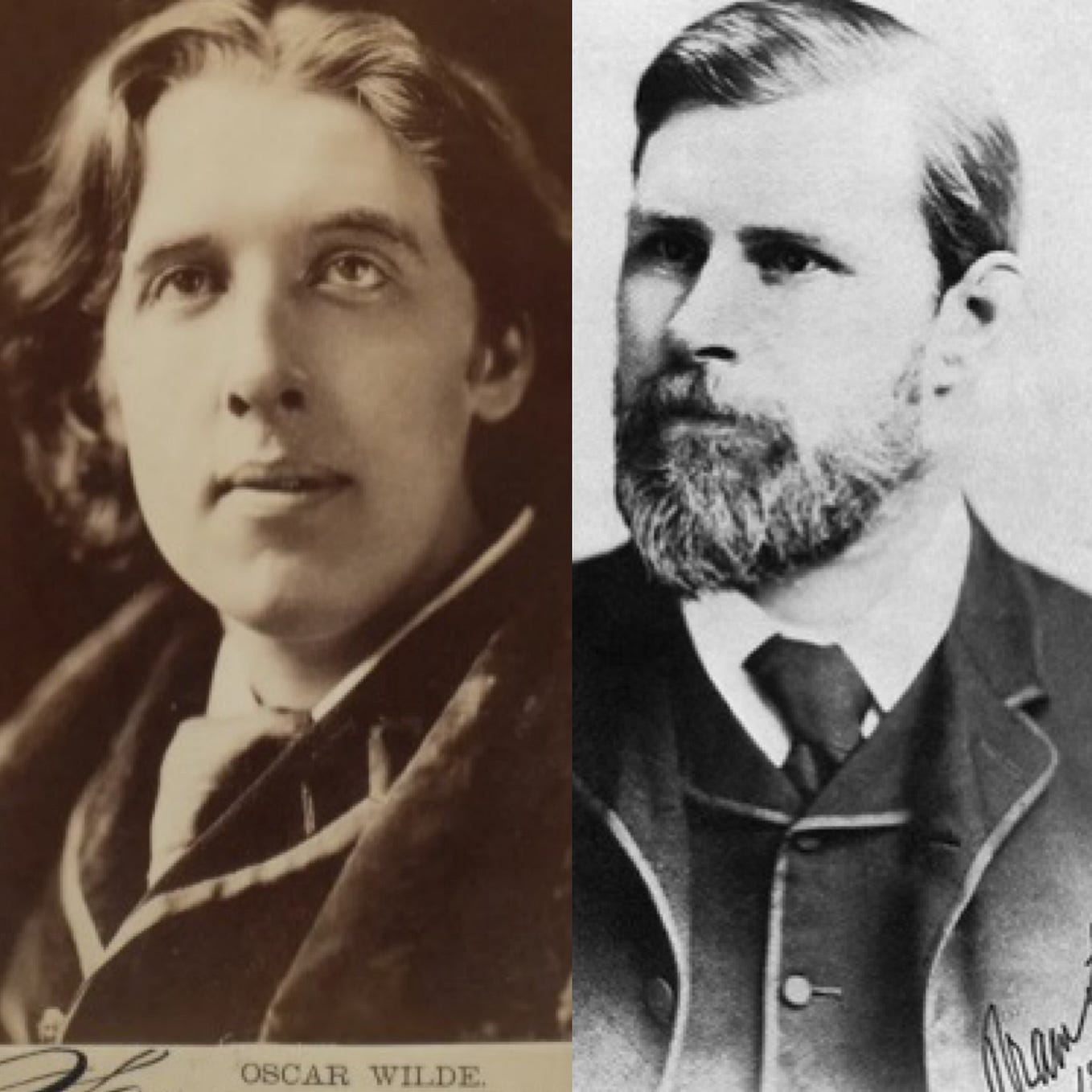

Florence Anne Lemon Balcombe was one of five daughters born to Lt. Col. James and Phillipa Balcombe in 1858 in Ireland. Even without a dowry, at seventeen years of age, Florence caught the eye of fellow Dubliner, Oscar Wilde.

“She is just 17 with the most perfectly beautiful face I ever saw and not a sixpence of money.”

Considered tall at 5'8", with blue-grey eyes and light brown hair, and a slim physique, Florence fit the Victorian definition of female beauty. But with four other sisters coming of age and no money to entice a spouse, Florence knew she would have to choose a husband wisely. And quickly. In Dublin, there was an infamous hostess: Lady Jane Wilde, writer, feminist, and poet who wrote under the pen name “Speranza.” Florence attended her literary salons and met the elite artists of the day. It was an environment that would change her life

At that time, Lady Jane’s son, Oscar Wilde, was an eligible bachelor, traveling frequently between England and Ireland, occasionally making appearances at his mother’s soirees. During one of these trips home, he met Florence at her parent’s home, and accompanied her to church, later boasting of her beauty in a letter to a friend. Soon, they were attending social events together, either at his mother’s house or in town. Oscar was smitten enough to give her a gold cross with his initials engraved on it. He also sent, “Florrie,” as he called her, a painting he did while vacationing at his family’s summer home in County Mayo with his friend, Frank Miles. Perhaps his time would have been better spent courting her in person rather than sending her watercolors if he was at all serious about marrying Florrie.

However, Florence was seeing another person during their two-year courtship. While Oscar was out of town, there was another, more regular visitor to Lady Jane’s dinner table and literary salon: the drama critic, Bram Stoker. And so it came to pass that nineteen-year-old Florence Balcombe entered into an understanding with thirty-one-year-old Bram Stoker. Bram was, in addition to his writing free theatre reviews, working as a clerk at Dublin Castle.

A touring production starring Henry Irving played Dublin and instantly made a fan out of Bram. After Henry had read his rave review, he invited the critic to lunches and post-show suppers, mostly so that Bram could listen to Henry recite monologues and muse over his plans to run his own theatre someday.

After a theatre producer died, Henry Irving was awarded the management of the Lyceum Theatre in London. Henry offered Bram the job as acting manager.

Bram Stoker had the sense to woo and wed Florence quickly once he was hired. They left Ireland shortly, just days after their wedding in 1878.

In marrying someone in a theatre management position, Florence may not have envisioned her honeymoon at Birmingham’s Plough and Harrow Hotel. That is where they began married life as they met up with Henry, still on tour. Bram wrote later Henry was, “mightily surprised to find that I had a wife — the wife — with me.” So began the expectations of what sort of personal life Bram Stoker would have as acting manager for the Lyceum Theatre, the reigning classical theatre of London, for the next twenty-four years.

For their first year of marriage, Florence and Bram lived right around the corner from the Lyceum Theatre, near Covent Garden, in a top-floor flat. Florence was thrown into the theatrical world of late nights and long tours, where sometimes her husband was away on tour for up to six months at a time.

Within a year, she and Bram had a son, Irving Noel Stoker, but the majority of Bram’s time was spent being at the beck and call of Henry Irving and the demands of the Lyceum Theatre. Florence was hired as a vestal virgin crowd filler in a production of The Cups, but usually, she was at home, raising their son, Noel. Occasionally, she would join him at an opening night or socialize with the theatre patrons after a show. For a time, she joined him during an American tour with the Lyceum Theatre.

Florence had learned from being one of five lively daughters and attending the soirees of Lady Jane that being a good hostess was a supreme asset. The Stoker London household usually had a sister of Florence or a brother of Bram’s in-residence with them. This was especially true after they moved to Chelsea, a more fashionable area of London. Now it was time for Florence to thrive. Through her social interactions, Gladstone met and called Florence, ‘the beauty.” She was invited to art shows, opening nights, and concerts. At her own literary salons, she entertained George du Maurier, W.S. Gilbert, John Barrymore, and Ellen Terry.

Ellen Terry was the leading lady at the Lyceum Theatre, she and Bram were hired on the same day. They went on to have a lifelong friendship, calling one another “Ma” and “Pa” to the annoyance of their employer, Henry Irving, and perhaps to Florence. Surely, the photograph that Ellen signed “The Honeymoon!”, the one of her and Bram traveling on tour, might have caused some hard feelings for Florence.

By some accounts, during Bram’s absence, Florence continued to be an in-demand member of the London literary set. People were so taken with her beauty that they would stand on chairs to take a look at her. However, this was also during the time of Oscar Wilde’s defamation trial, a proceeding that would cost him his career and his health. Florence’s correspondence at that time depicts her as more concerned with her portrait being painted than her former suitor’s ruin. Or perhaps there were letters that were later burned or hidden that would have shown her concern for Oscar’s loss of reputation and livelihood.

Florence was painted and sketched by some of the most prominent artists of the day. Burne-Jones, Walter Frederick Osborne, and Oscar Wilde himself sketched portraits of Florence, which were shown at parlors and drawing rooms around London.

During the long hours that Bram was keeping at the theatre, there was another project that was taking his time and attention away from Florence and Noel. It was his own writing. By 1890, Bram had written the short story, Under the Sunset, and the novels, The Primrose Path, and The Snake’s Pass. But it was his next novel, The Un-dead, later titled Dracula, that took all his time and attention.

As a child, Bram’s mother had told him ghastly folk tales of people being buried alive during the time of cholera. And Oscar’s mother, Lady Jane Wilde, had recited volumes of Celtic ghost stories and legends during her salons. Some have suggested that Bram was inspired by both women for his tale of Dracula. In 1897, he finally got to see his novel, Dracula, in print.

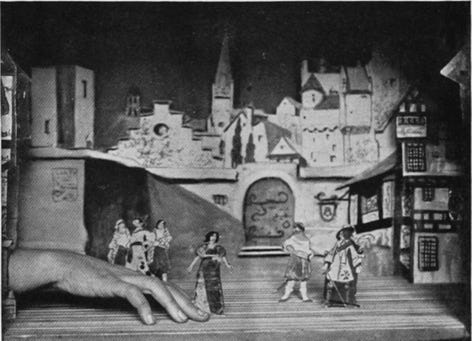

It was a critical, if not a financial success. Bram had tried to get Henry to mount a production of Dracula as a play. It was said that the vampire, a blood-sucking narcissist, was based on none other than the egotistical Sir Henry Irving. And although Henry allowed a read-through of the script at the theatre for copyright purposes, after Henry read it, he had only one word for it: dreadful. The Lyceum Theatre itself went bankrupt and ceased to operate by 1900.

Bram died in 1912, having written 12 novels in his lifetime, but he was never to know the worldwide success of Dracula.

Just after his death, cinema began to adapt works for silent films. In Germany, a filmmaker named Albin Grau working for Prana pictures produced Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror. It was basically a ripoff of Dracula, with “Nosferatu” substituted for the word “vampire.” Florence Stoker heard word of the film and began a seven-year battle for copyright infringement, stipulating that all film copies of Nosferatu be destroyed. Perhaps Florence had paid attention to Oscar Wilde’s legal proceedings based on defamation after all.

By a stroke of sheer luck, French film collector Henri Langlois managed to have one copy of the film that escaped the destruction of the Nazis during WWII. In 1947, the film Nosferatu: A Symphony of Horror was given to the Museum of Modern Art in New York City and then copies went to the National Film Archives in London and other European holdings.

Florence joined the Society of Authors and was eventually awarded £5,000 for infringement. Later, she read in a newspaper that Universal Studios had optioned the Dracula story, and once again she began legal proceedings to keep them from pirating her husband’s works. Because Bram Stoker had held a staged reading to enforce the copyright of his novel’s story, Florence had the stage rights and film rights to projects based on the book and she was determined to keep them.

In 1924, the London stage was finally granted permission to mount a production of Dracula. Not long after, Bela Lugosi took a staged production of Dracula to Broadway. It was booed and hissed by critics and yet made solid money for over a year. In 1931, a movie production company was awarded the right to make one of the first filmed movies of Bram Stoker’s work.

Over time, from the copy of the Prana production of Nosferatu, the silent film began to see the light of day. More and more copies of it appeared at smaller movie theaters. The legend of Bram Stoker’s Dracula began to take hold in the general population.

Florence went on to publish a missing chapter from Bram’s Dracula and titled it Dracula’s Ghost. She also spent her last decades dedicating her life to protecting her husband’s copyright. Even if Bram didn’t know that Dracula would become a worldwide success, Florence made sure the world knew that Bram Stoker was its author.

From a debutante without a penny to her name to an international champion, Florence became a tenacious advocate who fought lawsuit after lawsuit to protect her husband’s name and the right to his creation’s legacy. Florence Stoker died in 1937 at seventy-nine years of age, the unexpected heroine who kept Bram Stoker’s name alive.