Slate has relationships with various online retailers. If you buy something through our links, Slate may earn an affiliate commission. We update links when possible, but note that deals can expire and all prices are subject to change. All prices were up to date at the time of publication.

It’s been more than two decades since the late, great Ol’ Dirty Bastard, of the iconic New York rap posse Wu-Tang Clan, crashed the stage at the 1998 Grammys to bellow that “Wu-Tang is for the children.” The culture has since proved ODB correct. In a genre notorious for neglecting the memories, stories, and archives of its many elder statesmen, the Wu-Tang Clan and its music have continued to resonate in the popular imagination, and to influence even the kids of the fans who listened to the Staten Island crew throughout the ’90s. You can see evidence of this over just the past few years: an autobiography by member U-God, a Showtime docuseries directed by famed hip-hop journalist Sacha Jenkins, a Hulu series dramatizing the crew’s formation, multiple Verzuz faceoffs encompassing both the production and lyrical prowess of the group—and, of course, perhaps most infamously, the saga of the little-heard, multimillion-dollar album Once Upon a Time in Shaolin.

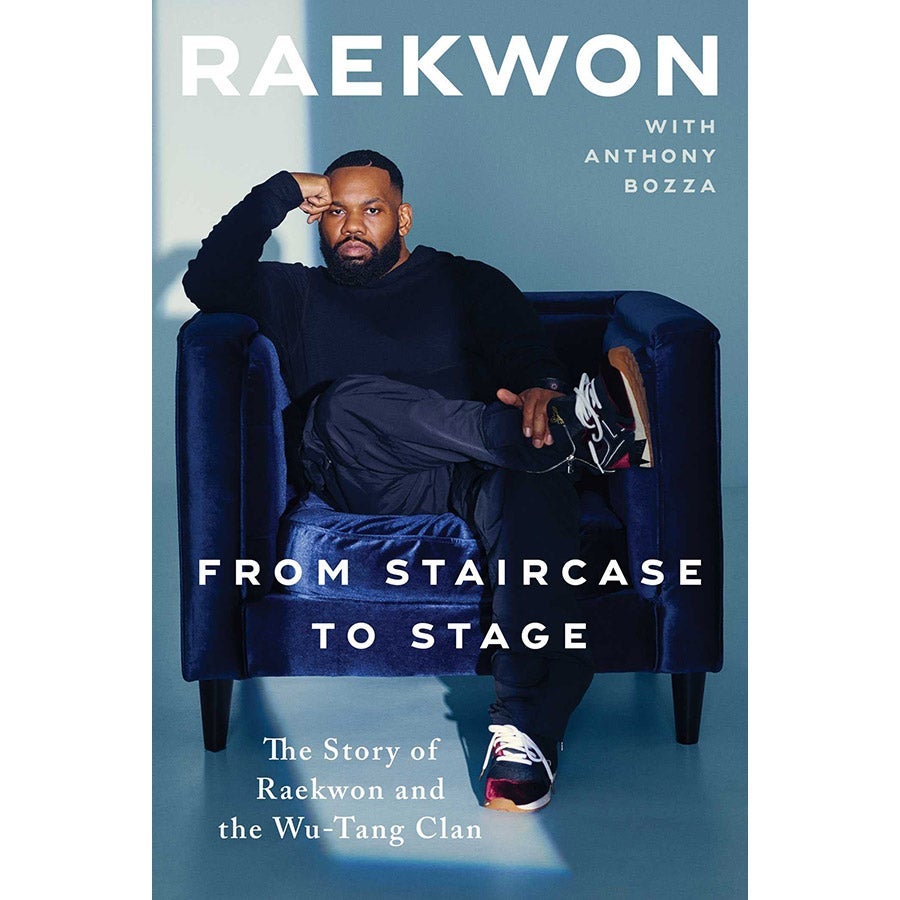

Now there’s a new memoir out by Raekwon the Chef, one of the most celebrated members of the group, titled From Staircase to Stage: The Story of Raekwon and the Wu-Tang Clan. Rae is best known for dominating a large chunk of Wu-Tang’s early work—including the group’s most beloved track, “C.R.E.A.M.”—but he has a staggering legacy in his own right, from his highly acclaimed solo work, to his collaborations with other Wu-Tang alumni like Ghostface Killah, to his guest verses for artists like Outkast and Kanye, to his record label and weed ventures. And he has more coming, including prequel and follow-up albums for his legendary Only Built 4 Cuban Linx series and a docuseries about the creation of the first Linx classic.

Most of the history of the Wu-Tang has been told through the eyes and with the oversight of its old ringleader, RZA, whom Slate interviewed just last year—but the Chef is ready to tell it how he saw it. The anecdotes within the book, some of which have never before been told, are eye-popping: Rae’s early dancing days, his original verse for “C.R.E.A.M.,” how Rae and Ghost squashed their beef with the Notorious B.I.G. the night before he was shot. Rae takes credit for popularizing brands like Cristal and even launching some film directors’ careers through his ideas for popular Wu-Tang music videos—and he makes a pretty convincing case all around. Most significantly, he has a lot of words about and for his old friend and mentor RZA, both praising his early creativity and leadership and condemning his financial exploitation and desire for absolute control, which seems to have divided the group up to this very day, especially when it comes to documents of their legacy like the Hulu series. Near the very end of From Staircase to Stage, Raekwon writes: “When RZA and his brother read these words, they are going to say I’m frontin’ on how they handled … the TV show. They’ll say it’s all bullshit. To that I say, ‘You know damn well I’m not lying.’ ”

A few weeks ago, I spoke with Raekwon over the phone about the timing of his new memoir, his upcoming projects, and the significance of who gets to write the Wu-Tang Clan’s history. Our conversation has been edited and condensed for clarity.

[Read: A Quixotic Attempt to Listen to Everything the Wu-Tang Clan Has Ever Recorded]

Nitish Pahwa: What made now the ideal time for you to release your memoir?

Raekwon: I guess the time is now because I’ve been in the business for over 25 years and I feel that I’m still growing with ideas and doing different things to motivate myself and others. Plus, this pandemic, it really dampened things on the outside. I had to really sit here and think about what I wanted to do to keep myself focused.

Have any other members of Wu-Tang read your book yet, or are they all going to be reading it at the same time?

I don’t know—books are dispersed to members. Of course, they’re happy for me. I got a lot of congratulation calls and things like that. I’m sure they going to vibe to it like everybody else.

A significant part of From Staircase to Stage concerns the origin of the term “C.R.E.A.M.” The book marks your first time explaining that in depth, right?

Right.

It’s an amazing story about how your cousin came up with the term because of a Tom and Jerry episode in which they’re making sandwiches overflowing with mayonnaise. Is that cousin who coined the term still around? Is he aware of the impact?

He’s still around. He’s one of my favorite cousins. He has a family. We laugh about things. He’s from Brooklyn. He’s just filled with slang. I guess that’s just how we grew up back then. That always has been a part of our lingo, our conversation. He never looked at it, like, “Yo, I’m famous for writing that.” He just knows that it’s a word that’s out there.

I was really struck by something else you wrote: that you were often in the room and giving a lot of feedback to the other members when they were recording their solo albums, whether that was Ol’ Dirty Bastard or Method Man. Do you feel like you’ve gotten the credit you deserve for those collaborations, as well as for the way you helped out some of your friends on their records?

I was being a team player because I believed in my family. I believed in my organization that I was working with. We had to learn to love each other, respect each other’s craft, be honest with opinions, be opinionated, be vocal when it’s time to be vocal. That’s always been my thing. If I brought something to the table, I didn’t ask for credit right away from it. If I felt like you forgot that I had a lot to do with the energy in the room, that’s when I’m going to say something, because there’s no I in team.

We were always thinking collectively. When we made Cuban Linx, Ironman, and 36 Chambers, we were all huddled up in a great way where opinions weren’t mutual, but they were respected. For me, I never looked for anything other than what it was when it was time to be spoken about. Sometimes, dealing with the crew, we could be in a situation where we’re not feeling a certain vibe of the music, and nobody’s saying nothing. Before I’m to say anything, I’ve got to make sure that’s how everybody feel. I’ve always been the vocal one to address situations because I know that’s the only way you can communicate, through conversation. We would have to bring it up. It’s called the “elephant in the room” action. You get that action, you know it’s real.

[Read: The Twenty Greatest Wu-Tang Clan Albums, Ranked. Blaaow!]

I’m also curious about the dynamics of your relationship with RZA throughout. You allude to the fact that RZA has presented himself as central to the continuing documentation of Wu-Tang, whether it’s through the recent docuseries or the exclusive album. Was there some part of you that wanted to offer your own perspective on what happened during those years?

Number one, what you guys are getting through RZA’s tunnel vision is his side of it, his story, the way he looked at it. That’s not what you’re getting in my lens. We know today, dealing with movies and docuseries, some things are being fictionalized for television purposes, and that’s just what it is. What you’re getting is a piece of RZA’s mind. When you read my vision or see my vision, it’s going to be Rae’s version. As far as us adding on collectively, we didn’t have a lot of time to elaborate with RZA’s vision. At the end of the day, we participated because we’re going to support it. Then he’s going to take it to the next levels according to what his vision made present at the time. We understand this business, but always know that that’s what makes the Clan so different—we all have different perspectives. Imagine dealing with nine guys and them telling you their stories. It’s always going to be different sides and different opinions to things.

At the end of the day, this is what brings out the best of us, because you get to see Rae’s vision now. It’s like giving you the West Side Story vision right now. RZA’s trying to make it this way, and me, when you see my shit, you might be like, “Yo, it’s Goodfellas, this shit reminds me of Martin Scorsese.” I’m giving you something to represent through my lens. When you get it, you want to be like, “Holy shit, this is through Rae’s eyes. This shit is serious.” You get it?

I get it. After U-God’s memoir and now yours, do you think other Wu-Tang members are going to release their own autobiographies?

Yes. I haven’t heard it verbatim from the men, but I’m sure that brothers are thinking that way because this is what people love about us. They love to be able to get in the minds of their Wu brothers and want to see what they’re thinking.

The other thing I want to say is that Wu-Tang was created for a common cause. We were competing with one another to be great, to be able to go out there and represent our school of learning to the world. We’ve always been that crew creating competition with each other because that’s what made us better. As far as it being presented to the world that way, we never lied. When we told you we all had different styles, that’s what it meant. It meant different styles clashing with one another to make something great that you guys could go back and say, “Wow.”

Our job and our duties was to make a masterpiece by any means. We were putting the room together and said, “Yo, this is an organization. Each man is going to have to earn.” You’re going to have guys that’s going to work at a certain level of respect because they know that they’ve got to earn. It’s always been a competition. If I’m sitting here and I’m making motherfucking money and he ain’t making no money, he’s going feel a certain kind of way. This group was Super Friends showing off their utility belts, giving you their powers, but giving it to you in a way where competition was always a must in order to be better.

From Staircase to Stage: The Story of Raekwon and the Wu-Tang Clan

By Raekwon. Gallery Books.

At the very end of the book, you mentioned there are still some ongoing legal things that you can’t really speak to right now. I’m not going to ask about those, but I’m wondering what your thought was behind releasing the book while those legal battles are still occurring, with RZA and other Wu-Tang-related properties?

Let’s get this straight. I don’t address other situations that doesn’t have anything to do with what we are doing. There’s no turbulence between myself and RZA on any aspect at this moment. I think we just not speaking on things that we are not fond of—knowing you can’t talk about stuff you don’t know. That’s the purpose. Other than that, it’s about releasing a great book, giving the people what they want, the excitement of a memoir from the Chef, because a lot of people know I love to talk.