This Chinese monk's epic, east-to-west travels rival Marco Polo's

In the 13th century, a Mongolian khan sent Rabban Bar Sauma west to forge diplomatic ties with powerful leaders from Persia to Paris.

Two travelers from the 13th century made remarkable journeys. The man who headed east, from Europe to Asia, became a household name, thanks to his travelogue, The Travels of Marco Polo. The name of the other man is less well known, but his accomplishments are just as remarkable. Rabban Bar Sauma left China in 1275, followed the Silk Road, and made his way to Baghdad, Constantinople, and France, meeting khans, kings, and a pope.

The remarkable Bar Sauma was born in Zhongdu, China, in 1220. His ancestors were descendants of the Uighurs, a Turkic ethnic group from Central Asia. Bar Sauma was brought up in the Nestorian faith, a Christian denomination that originated in Asia Minor (modern-day Turkey) when it broke away from the church in the fifth century. Nestorianism took root in Persia and then spread east to China.

“Rabban” is an honorific: In the Semitic Syriac language in which the Nestorian liturgy is written, it means “master.” At age 23 Bar Sauma became a monk, and he spent most of his adult life as a teacher.

Unlike Marco Polo, who embarked on his famous journey when he was just 17, Bar Sauma did not begin his traveling until middle age. At age 55, he decided to visit the holy sites where his religion was founded. In the course of his extraordinary travels, Bar Sauma would later form an unlikely Mongol-Christian alliance to seek Europe’s help against Muslim armies.

Silk Road trip

Bar Sauma’s initial objective, however, was simply to walk in the Holy Land lying in the far west. His pupil Rabban Marcos would travel with him. Before leaving their homeland, the two sold all of their belongings and set out.

Like Polo, they benefited from Genghis Khan’s unification of the territories surrounding the Silk Road. They traveled during a period of stability historians call Pax Mongolica, but it did not mean the journey was without perils: The two pilgrims often went through deserts to avoid unsavory encounters on the standard route. At one stage, they crossed the Taklimakan Desert, where they had to scale 60-foot dunes and find shelter from turbulent sandstorms. (Here's the surprisingly simple origins of the Silk Road.)

From there, the pair reached the oasis of Hotan in western China, after which lay Afghanistan’s mountains, and then a long slog west through the Iranian desert. After two years they reached Baghdad, seat of the catholicos, or patriarch, of the Nestorian Church. Bar Sauma and Marcos were intent on reaching Jerusalem, but conflict in the Holy Land made that impossible. Instead, the two traveled to Armenia and stayed in monasteries there before being recalled to Baghdad by the Nestorian catholicos, Denha I.

ORIGINS OF NESTORIANISM

Rabban Bar Sauma belonged to the Christian denomination known as Nestorianism. The faith is named for Nestorius, the patriarch of Constantinople in the fifth century who believed that the mortal and divine natures of Christ were separate from each other. His doctrine was rejected at the Council of Ephesus in 431, and Nestorius’ supporters broke away to form their own church. Nestorianism grew popular in Syria and Persia before spreading eastward to China. In 635 the emperor Taizong received a Nestorian monk, an encounter recorded on the eighth-century stela of Xi’an.

Founded in the eighth century by the Abbasid Muslims, Baghdad had been conquered in 1258 by the Mongols and become part of the Mongol Empire. The Ilkhanate, as the region was called, was ruled by an ilkhan, a deputy to the Great Khan in China. On Bar Sauma’s arrival the ilkhan was Abagha, a descendant of Genghis Khan. The Mongols had a fearsome military reputation, but their rule in this period was marked by religious tolerance. Abagha, a Buddhist, was sympathetic to the Nestorians.

The catholicos Denha decided to send Bar Sauma and his disciple to meet Abagha and receive the khan’s secular blessing for his ordination as patriarch. During the trip, Denha appointed Marcos to his first senior position in the Nestorian Church. Denha planned to send the pair back to China, but in 1281 he died. A replacement was sought, and Marcos was chosen as the new Nestorian patriarch. Marcos assumed his new role under the name Mar Yahballaha III, and his former master would continue his travels.

Abagha died in 1282, was briefly succeeded by his brother, and then, by his son, Arghun in 1284. In this period, the Egyptian Mamluk Muslims had gained control of the Holy Land and were posing a military threat to the khanate. The ilkhan elected Bar Sauma as head of a delegation to Europe to convince its leaders to join a military campaign against their common enemy. Then in his 60s, Bar Sauma began traveling west in 1287 on a new journey, with Constantinople as his first destination among many. (Istanbul’s ancient imperial legacy lies hidden in plain sight, even today.)

Monk on a mission

The Byzantine capital made a colossal impact on Bar Sauma. It was his first time in an entirely Christian city—and what a city it was—with its blend of Roman and Byzantine splendor. The Nestorian pilgrim was dazzled by the magnificent sight of Hagia Sophia, built seven centuries earlier by Emperor Justinian I.

From Constantinople he traveled to Italy in June 1287. His first stop was Rome, where he hoped to convince the pope to declare a new crusade to take the Holy Land from the Mamluks. Pope Honorius IV, however, had just died and his successor had not yet been chosen. Bar Sauma’s message would have to wait, so he made the most of his time waiting by visiting Rome’s basilicas and the relics of the holy figures he had so venerated in far-off China. After visiting the tomb of St. Paul and the Church of St. Peter in Chains, he set off to meet the French king Philip the Fair.

Bar Sauma’s quest for a joint alliance was stymied by the fragmentation of power in Europe. The French monarch was more worried about English control of the French region of Aquitaine than with the Holy Land. The king made only vague promises. Bar Sauma used the opportunity to visit Paris, its university, and its churches. In his writings he mentions a “Great Church wherein were the funerary coffers of dead kings,” probably referring to the Basilica of Saint-Denis. He made no mention of the massive Notre Dame Cathedral, but historian Morris Rossabi suggests that he may have been unnerved by it, as Nestorians did not venerate Mary as the “mother of god.” (Discover the 800-year history of Paris's Notre Dame Cathedral.)

Bar Sauma completed his round of royal visits by presenting himself to Edward I of England, then residing in Bordeaux. Edward promised him economic and military aid that would never materialize. Even so, the encounter impacted Edward: In 1291 he sent an envoy, Geoffrey of Langley, on a diplomatic mission to the Ilkhanate.

In February 1288 a new pope, Nicholas IV, was elected, and Bar Sauma immediately set about petitioning him. The pontiff entrusted the traveler with a letter for Arghun Khan, a copy of which is kept in the Vatican archives. In it, the pope declined the alliance owing to the fragility of the internal situation in Europe and exhorted the ilkhan to convert to Christianity. However, Bar Sauma had piqued his curiosity, and the Chinese diplomat was allowed to celebrate Mass according to Nestorian customs. Nicholas IV noted that, apart from the language, the Mass celebrated by the “ambassador of the Mongols” resembled those celebrated in the West.

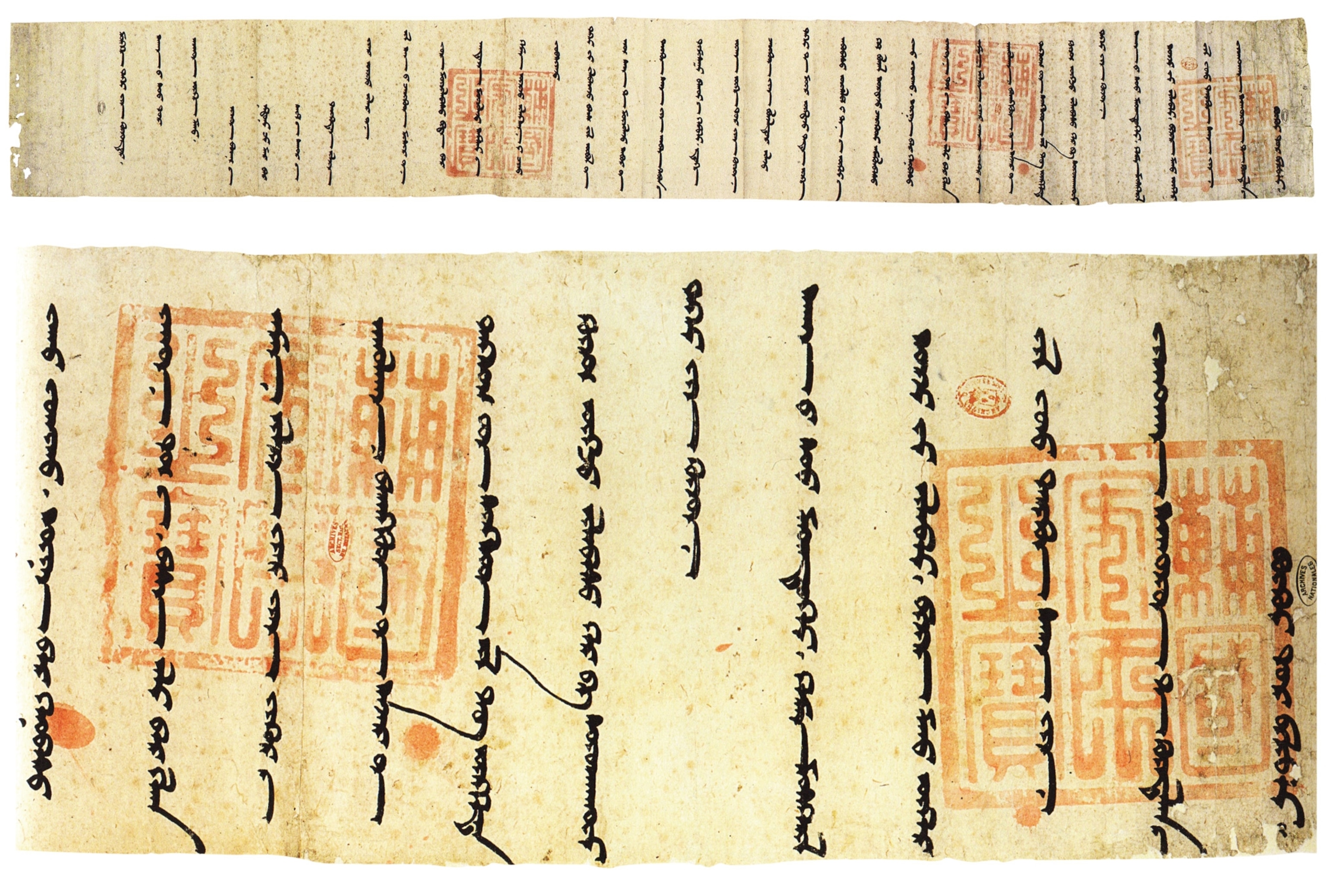

THE LOST MANUSCRIPT

The little knowledge scholars possessed about Rabban Bar Sauma was drawn from a few documents in Europe that record his visit there. Then in 1887 a manuscript in a monastery in present-day Iran was found, which turned out to be a dream discovery: a translation into Syriac of Bar Sauma’s own account of his travels from China to Europe, written in Persian in the last years of his life. By linking the account with other manuscripts held in London and the Vatican that mention Bar Sauma, historians were able to form a much better picture of the experiences of this remarkable traveler.

Rabban Bar Sauma’s long journey had come to an end. He headed back east and would die in Baghdad in 1294, a guest of the patriarch Mar Yahballaha III, his former novice who had left China with him 20 years earlier. As the first known traveler from China to Europe, Bar Sauma must have appreciated the momentousness of what he had seen. To the eternal gratitude of historians, he spent his last days in Baghdad recording his impressions, and a copy of this extraordinary account was discovered centuries later.

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- California brown pelicans are starving to death—despite plenty to eatCalifornia brown pelicans are starving to death—despite plenty to eat

- The world's largest fish are vanishing without a traceThe world's largest fish are vanishing without a trace

- We finally know how cockroaches conquered the worldWe finally know how cockroaches conquered the world

- Why America's 4,000 native bees need their day in the sunWhy America's 4,000 native bees need their day in the sun

- Crowdsourcing an anti-poaching movement in South Africa

- Paid Content

Crowdsourcing an anti-poaching movement in South Africa

Environment

- 2024 hurricane season forecasted to be record-breaking year2024 hurricane season forecasted to be record-breaking year

- Connecting a new generation with South Africa’s iconic species

- Paid Content

Connecting a new generation with South Africa’s iconic species - These images will help you see coral reefs in a whole new wayThese images will help you see coral reefs in a whole new way

- What rising temps in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlifeWhat rising temps in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlife

- He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?

History & Culture

- I wrote this article with a 18th century quill. I recommend it.I wrote this article with a 18th century quill. I recommend it.

- Why this Bronze Age village became known as ‘Britain’s Pompeii’Why this Bronze Age village became known as ‘Britain’s Pompeii’

- These modern soldiers put Bronze Age armor to the testThese modern soldiers put Bronze Age armor to the test

- Should couples normalize sleeping in separate beds?Should couples normalize sleeping in separate beds?

- They were rock stars of paleontology—and their feud was legendaryThey were rock stars of paleontology—and their feud was legendary

Science

- Epidurals may do more than relieve pain—they could save livesEpidurals may do more than relieve pain—they could save lives

- Why the world's oldest sport is still one of the best exercisesWhy the world's oldest sport is still one of the best exercises

- What if aliens exist—but they're just hiding from us?What if aliens exist—but they're just hiding from us?

Travel

- Return to the wild: Connecting with Canada's heritage

- Paid Content

Return to the wild: Connecting with Canada's heritage - A practical guide to cycling Slovenia Green RoutesA practical guide to cycling Slovenia Green Routes

- This road trip journeys through Albania's wild, blue heartThis road trip journeys through Albania's wild, blue heart

- This less crowded ancient temple in Laos rivals Angkor WatThis less crowded ancient temple in Laos rivals Angkor Wat