Obituary: Eduard Shevardnadze

- Published

Proponent of glasnost

Eduard Shevardnadze, who has died aged 86, was virtually unknown outside Georgia when Mikhail Gorbachev made him Soviet foreign minister in 1985.

But his lack of experience in foreign affairs was more than made up for by his desire to push through reform.

He played a leading role in the arms agreements that greatly reduced the risk of a nuclear war.

But he was later toppled as leader of his native Georgia amid allegations of corruption.

Eduard Shevardnadze was born on 25 January 1928 in the city of Lanchkhuti in the Transcaucasian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic.

Luxury cars

This area of the former Soviet Union encompassed Armenia, Azerbaijan and Georgia.

His father was a teacher and also a committed communist, a view that was not shared by his mother, who tried to persuade father, and later son, to renounce their political activities.

He joined the Communist Party's youth movement in 1946 and rose rapidly through the hierarchy to become Georgian party boss in 1972.

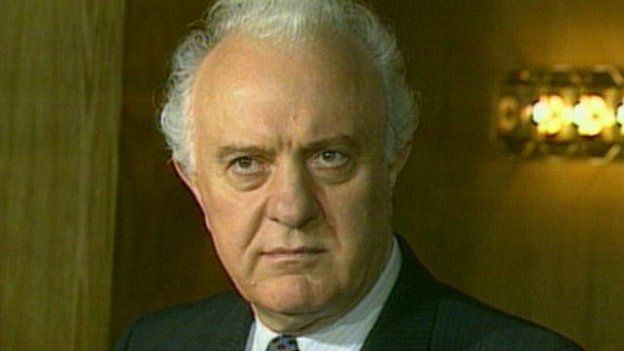

Together with Mikhail Gorbachev he helped end the Cold War

During the 1970s, he fought against bureaucracy and introduced free-market reforms.

He was particularly keen to clamp down on corruption in the Communist Party, stripping hundreds of officials of their luxury cars and villas and dismissing many others.

Indeed, Shevardnadze's reforms were so great as to lead some to suggest that the policy of openness - glasnost - was introduced not by Gorbachev in the 1980s but by Shevardnadze in the 1970s.

As Soviet foreign minister between 1985 and 1990 when the Cold War began to thaw, he oversaw a transformation in Soviet foreign policy.

Resignation

With hardly any experience of foreign affairs, he became an ambassador for the new Soviet policies of glasnost and perestroika - openness and restructuring.

He negotiated a series of remarkable arms control agreements, including the Intermediate Nuclear Forces treaty which eliminated a whole class of atomic weapons.

He withdrew Soviet troops from their bloody intervention in Afghanistan and paved the way for the independence of the former Iron Curtain countries of Eastern and Central Europe by ending the Soviet military presence.

"You know," he said in a 2010 interview, "we truly did change the world then… and the main merit goes to Gorbachev."

He survived this assassination attempt in 1995

A champion of Moscow's new warm relationship with the West and a friend of the US Secretary of State, James Baker, Shevardnadze's liberal views brought him many enemies among hardliners at home.

His dramatic resignation, in December 1990, took even President Gorbachev by surprise.

Alarmed that the Soviet leader might be giving ground to conservative elements, Shevardnadze dramatically warned that the USSR faced a looming dictatorship.

Eight months later, in August 1991, when the tanks rolled into Moscow during the attempted coup, Shevardnadze's prediction seemed to have come true.

Shortages

He joined Boris Yeltsin on the barricades to defy the plotters.

The coup failed within days and Shevardnadze was, for a month, the foreign minister once more, of a now disintegrating Soviet Union.

His native Georgia was disintegrating too, into factional violence. A civil war raged and the collapsing economy brought with it food and fuel shortages.

In March 1992, Shevardnadze returned to the capital, Tbilisi, after the Georgian president had fled. Unopposed in leadership elections, he struggled to impose order, even on his own parliament.

He managed to quell the bloody civil war, but the country remained unstable.

Voting in the 2013 elections in Georgia

In 1995, shortly after surviving an assassination attempt, he was elected president of Georgia.

Apart from a continuing problem of separatism, he faced political conflict with neighbouring states over the routing of an economically vital pipeline from the nearby Baku oilfields.

But, with corruption still rife, Shevardnadze found himself beset by calls for even more political reform.

Things finally came to a head in November 2003 when, after he won a disputed victory in Georgia's presidential election, he was toppled by a popular revolution.

His critics, who invaded the Georgian parliament, accused Shevardnadze of being just as corrupt and anti-democratic as those he had replaced. He had little option but to resign.

"I think," he said, "that my resignation was the only way to avoid bloodshed."

Eduard Shevardnadze was blessed with an easygoing personality, far removed from that of his predecessor as Soviet Foreign Minister, Andrei Gromyko.

His international stature made him a natural leader for Georgia but it also brought him face to face with new political realities.

Shevardnadze claimed, with some justification, to have helped end the Cold War, liberate Central Europe, reunify Germany and democratise the USSR.

But the man who once preached the importance of furthering democracy was toppled by those whose definition of the term was radically different from his own.