Why human bodies are medicine's most essential taboo

Examining the dark history of anatomical dissection through the centuries—and why the need for study on human donors is as vital as it’s ever been.

Read something—this article, say—and you are probably doing so with your eyes, or listening with your ears, and processing it with your brain. Your brain is being fueled by blood which is being propelled by your heart. And the oxygen in that blood is being loaded in by your lungs. We all know that. But in the not-so-distant past, we didn’t— and it was someone’s job to work it out.

What a bit of you does, where it is, when it can go wrong and how it can be fixed have been the guiding questions of human anatomy since the Renaissance. And the most uncomfortable reality of just about any branch of medicine since is this: Most of what we know about ourselves comes from someone looking very closely at the inside of a corpse.

Where those corpses (cadavers, to use the medical term) came from in times past is a dark thread to follow. It forms part of the story explored by an exhibition in Edinburgh—a city with a centuries-long history of being the world centre of anatomical study. Anatomy: A Matter of Death and Life is on display at the National Museum of Scotland (NMS) and is perhaps not for the faint-hearted—though in many ways, it’s a subject we’re all a little more sensitive about than we used to be.

“I think death is definitely something we talk about a lot less today than in the past,” says exhibition curator Sophie Goggins. “People were confronted with death a lot more often. People died younger, medical care wasn’t what it is today. Things we would see as simple illnesses were more likely to carry off a member of their family.”

What happened to that member of the family was and remains a mostly formatted and ceremonial affair. But part of what the exhibition tackles is, were it not for the bodies that fell outside of these rituals, our collective health would probably be in a lot of trouble.

(Related: the environmental toll of cremating the dead.)

Gold standard of teaching

“If you go back into history and you look at individuals like Vesalius, Da Vinci—the absolute titans of anatomy and medicine—all of the big breakthroughs came from actually studying the real human body,” says Tom Gillingwater, Professor of Anatomy at the University of Edinburgh. “Actual experience-based anatomy, both from a teaching perspective and a research perspective, has historically been the absolute bedrock of properly understanding the human body, and dispelling a lot of incorrect knowledge about how we work and what we’re made of. And it’s still the gold standard.”

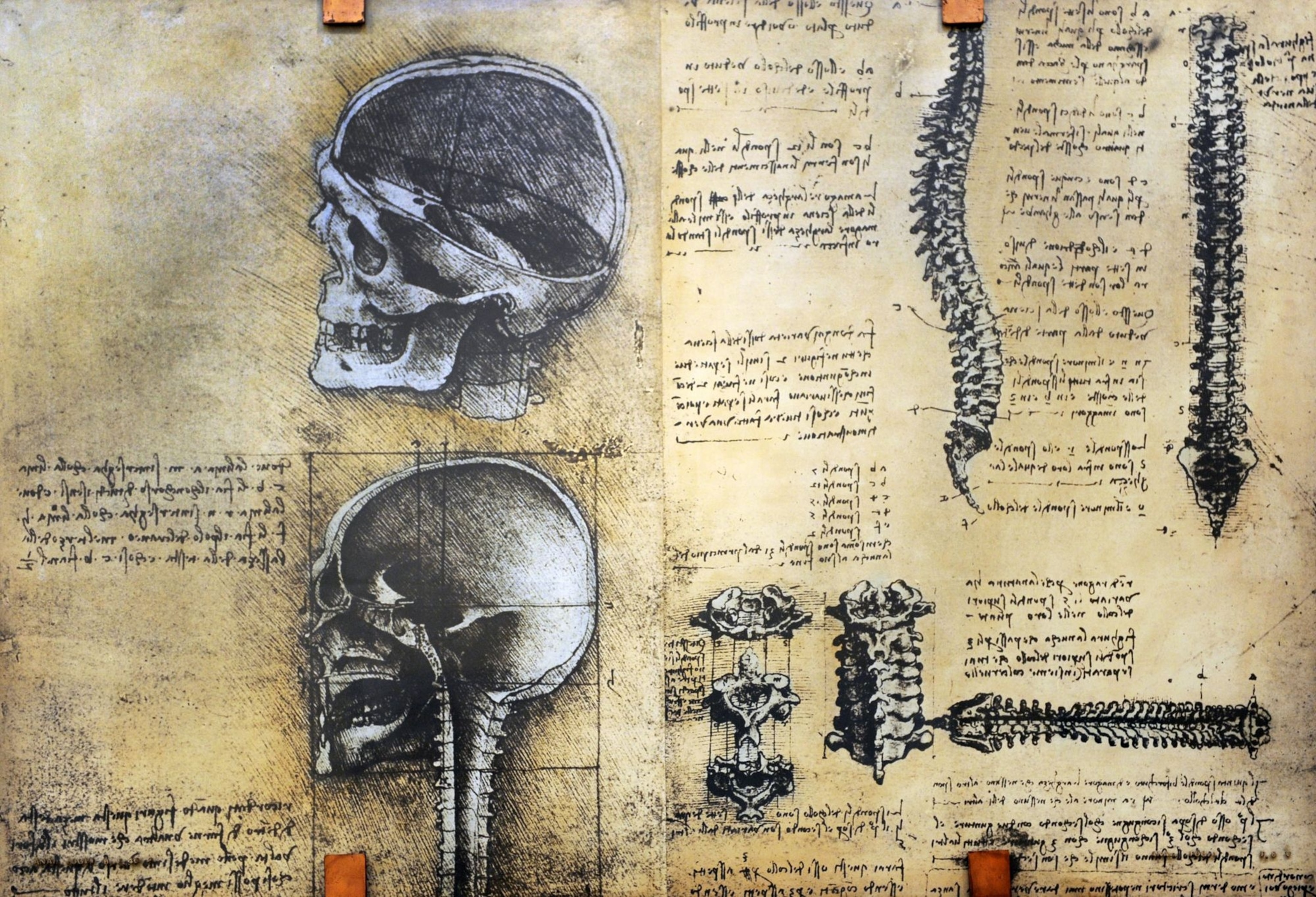

It was Da Vinci’s work that perhaps demonstrates the first serious attempt to understand what was going on beneath our skin. Following early work on bones whilst working for the Duke of Milan around 1495, Da Vinci’s desire to explore anatomy stalled due to his lack of access to corpses.

It would reignite following his dissection of an elderly man, the 'centenarian', who died in a Florence hospital during the winter of 1507 and with whom Da Vinci had the opportunity to speak before his death. Later working in Pavvia with a surgeon named Marcantonio della Torre, the Renaissance polymath is said to have dissected some 30 further cadavers and produced his most famous anatomical sketches—several of which feature in the exhibition. Around 250 of these, along with copious notes, were drawn in the first decade of the 16th century and formed the basis of Anatomical Manuscripts A and B—a body of work now part of the Royal Collection Trust and owned by the Crown.

(Explore Da Vinci works from the Queen's private collection.)

A true meeting of art and science, Leonardo’s work was packed with prescient insights—the form of the spine, the workings of the heart and potential diseases of the liver—that were well ahead of their time. So far ahead, in fact, that his failure to publish them as he’d hoped set the science back centuries. As Sophie Goggins puts it: “He discovered things about the structure of the heart that wouldn’t be rediscovered for 300 years,” adding that Leonardo’s work, though controversial in some quarters, “was seen as a beautiful pursuit of knowledge. It wasn’t something that was done secretly… it wasn’t dark and spooky.”

A fate worse than death

Unfortunately, however benign the pursuit of knowledge Da Vinci displayed, such virtuous associations around the dissection of human remains wouldn’t linger.

“As with most things historically, religion played a big role,” says Goggins. “In Da Vinci’s time, dissection wasn’t something that was frowned upon by the church. But later on it was. In many Christian religions, the idea of a body being together and whole when buried was important—and didn’t mesh very well with the idea of being dissected.”

With the expansion of medical knowledge gathering pace during the Scottish Enlightenment, Edinburgh in particular became a centre for the study of anatomy. And one critical thing remained in ever-shorter supply.

“Anatomy as a subject was a victim of its own success,” says Tom Gillingwater. “The situation was, if you wanted to be the best anatomist or the best medic you went to Edinburgh. People came from all over the world.”

Before long, it wasn’t just the University that was looking for bodies with which to teach. “All these entrepreneurial individuals set up additional pure anatomy schools, and so demand for bodies was going to go through the roof,” says Gillingwater. “The pressures on the anatomists to deliver must have been immense. And at the time there was not a sufficient arrangement to supply the bodies.” So began a series of events that, Gillingwater concedes, “brought the subject into disgrace.”

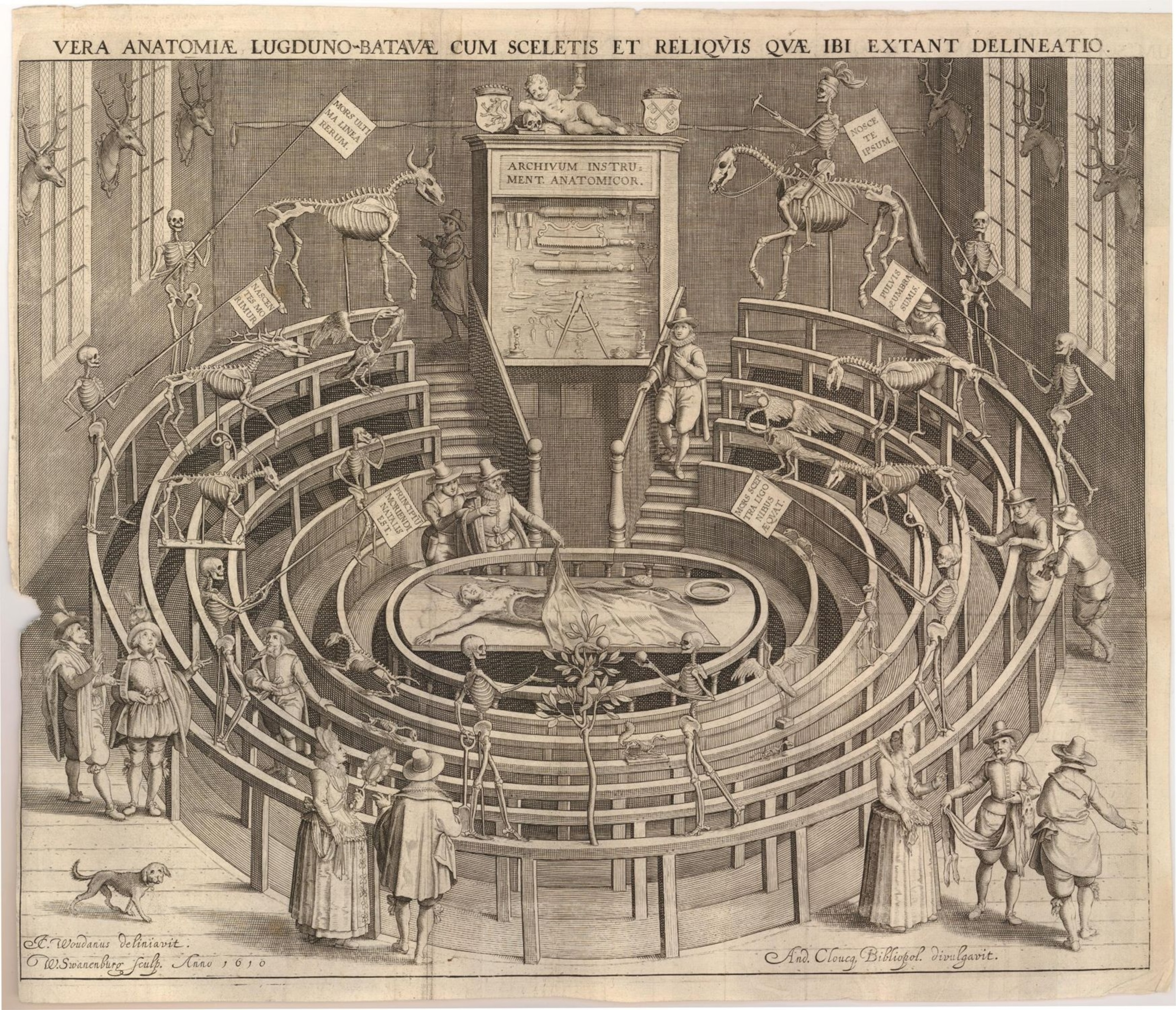

Prior to the Anatomy Act of 1832—more of which in a moment—the most reliable legal way for an anatomist to legally obtain a body for dissection was to become the recipient of an executed criminal tried for a capital crime, as per the Murder Act of 1752. The resulting procedure was not only for the anatomist’s benefit; it was a component of the legal process, and a dreaded one. “As part of the punishment you would be also be dissected,” says Goggins. “Publicly dissected. It was meant to deter you for committing that kind of a crime.” A total of 110 corpses of murderers were supplied for dissection in Scotland between the passing of the murder act in 1752 and the Anatomy act in 1832.

While medical schools were grateful for the grim commodity, it was a dubious tally to rely on—and if the deterrent proved successful, the situation for medical schools would be even worse. Sure enough, with falling numbers of executions and rising numbers of medical students in the early 19th century, demand for fresh cadavers swiftly outstripped supply.

While modern sensitivities mean most turn away from death, it wasn’t always so. In the 19th century, death was entertainment. “Public executions were one of the biggest draws in a city,” says Tom Gillingwater. “Today the thought that we’d all turn up in Trafalgar Square or at the Grass Market [in Edinburgh] to watch someone being hung… people are revulsed by the idea. But back then they drew huge crowds. And you could also buy tickets to public dissections. So in many ways people were more educated as to their own anatomy than today’s public are.”

This eagerness for knowledge—tinged with no small amount of voyeurism to peer at what one 1809 commentator called ‘a body filled with guilt’—fueled interest in criminal dissections, the so-called ‘dangerous dead.’ It also added to the pressures on anatomists not only to find bodies to dissect for their students but to preserve a lucrative income for their school, or image-saving charitable donations, via ticket sales.

It is around this time the word ‘bodysnatcher’ enters the anatomy conversation. There were other words, too: ‘resurrectionists’, ‘grave robbers,’ ‘Sack ‘em up men’ and ‘corp’ lifters.’ Whatever their name, the aim was the same: empty fresh graves and sell the body within to an anatomist willing to turn a blind eye to another rather unsavoury source of cadavers.

Bodysnatching was so routine by the turn of the 19th century, particularly around Edinburgh, that an array of tactics were employed to discourage the maleficence. Sophie Goggins notes two of these in the exhibition: the mortsafe, which took the form of a heavy metal coffin or fence apparatus that literally caged the dead in the churchyard. And the ‘coffin collar’—an iron hasp laid across the deceased’s neck and bolted to a piece of wood on the floor of the box and prevented the body being dragged out.

As the situation became ever-rife, watchmen were placed in graveyards. One Reverend Fleming of West Calder outside Edinburgh, wrote in 1821 that before these were installed, “the persons interred did not remain in their graves above a night, and that these depredations were successfully carried on for nine successive winters.” Such deterrents, says Goggins, were only needed to “protect bodies—or allow them to decompose long enough so they wouldn’t be of use to anatomists any more.”

Body manufacture

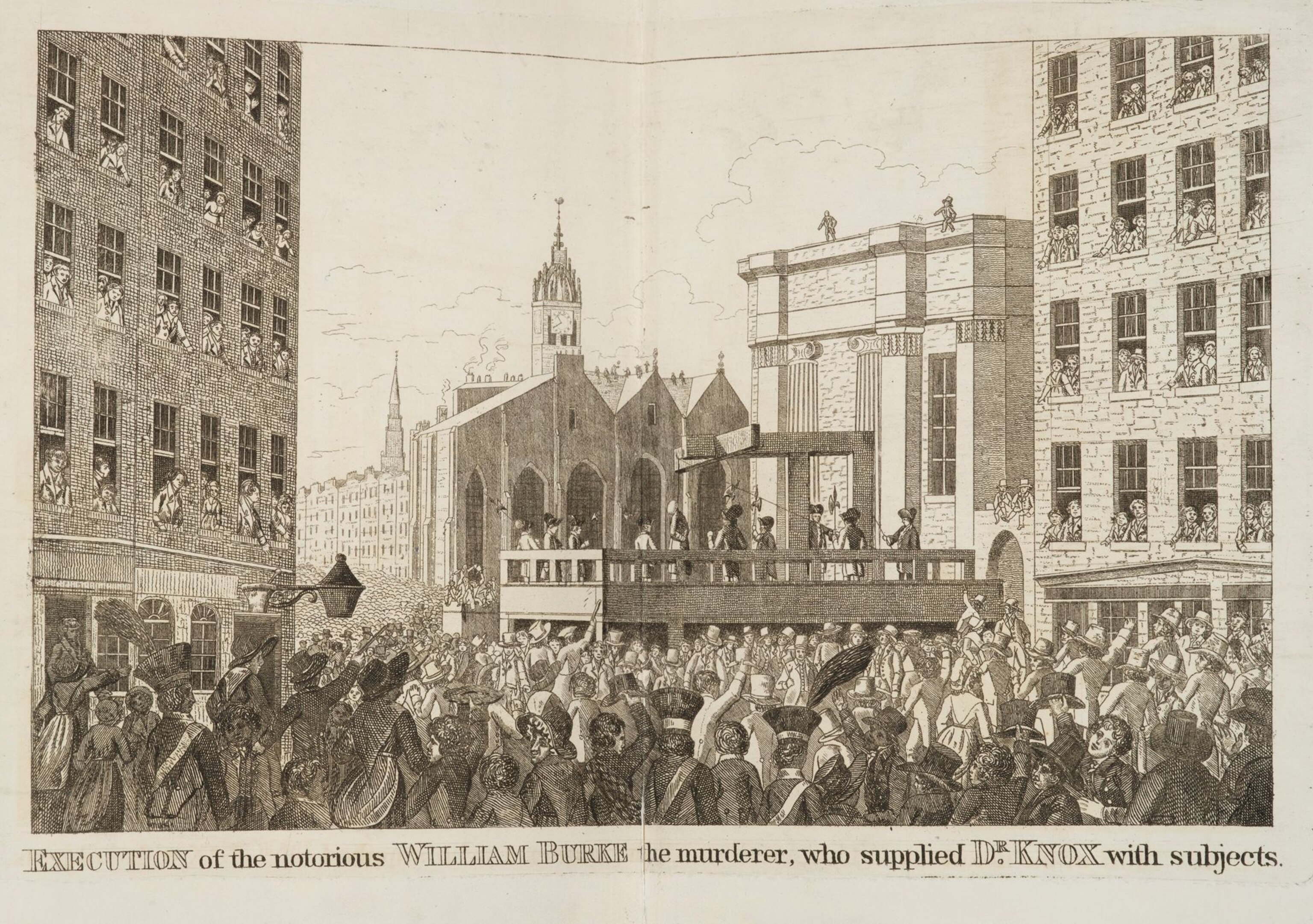

In the face of such measures, in 1828 Irish criminals William Burke and William Hare cut a corner by not only providing bodies but making them. This required an even more unscrupulous pair of hands on the anatomy table. Those belonged to Robert Knox, who paid William Hare between $10 and $12 for fresh corpses delivered to his laboratory at Surgeon’s Square, Edinburgh—despite, according to Tom Gillingwater, surely knowing that “he was handling freshly murdered bodies.”

Burke and Hare are thought to have killed 16 individuals in a spree that became known as the West Port Murders. Though oft-confused, of the pair it was Burke who in 1829 took the drop for the sole convicted crime of murdering Marjory Campbell Docherty, with Hare turning evidence in exchange for immunity (as Goggins says, “I think of ‘Hare’ like the rabbit… Hare got away”.)

Dissection was, with no small irony, part of his punishment.

Tickets were sold from surrounding viewpoints for his hanging to a crowd of some 24,000, and his subsequent dissection caused a riot amongst a crowd desperate to get a look. The procedure was accessorised with some ghoulish touches; a book covering was made from his skin, and a macabre letter penned by the attending anatomy professor Alexander Monro: “This is written with the blood of Wm Burke,” it reads, signed-off with the specific detail that “the blood was taken from his head.” Burke’s preserved skeleton—on display in the exhibition—was donated to the Surgeon's Hall Museum of the Edinburgh's Royal College of Surgeons.

However well-publicised the Burke and Hare murders, and this they were—the newspapers ensured “public revulsion and interest… the crime podcast of its day”, says Goggins—it was insufficient to deter the lucrative criminality that led to Burke’s grisly end. Quite the contrary, in fact. “There was a copycat group of murders in London called the London Burkers,” Goggins explains. Moreover, they entered the vocabulary. “‘Burking’ became a kind of verb for smothering someone and selling their body for dissection.”

“When there’s so much money to be made and the demand was so high, people were going to take opportunities,” says Tom Gillingwater. “Anatomy paid the ultimate price… but in many ways got off quite lightly.” Robert Knox, the anatomist at the centre of the Burke and Hare case, was manoeuvred out of the profession but never prosecuted for his role.

‘Punishment for being poor’

However unwittingly, with anatomy ostensibly being the root of such behavior something needed to be done. And in 1832, it was. The press attention gained by the London Burkers led to the now infamous Anatomy Act. This act of law widened the legal net to procure bodies to be used for dissection. Specifically, it allowed remains from hospitals, prisons and workhouses to be sold to licensed anatomy institutions if unclaimed for 48 hours.

As such, dissection developed from a cruel and unusual punishment to a social schism that was merely cruel. “Post 1832 dissection became a punishment for being poor, rather than punishment for a crime,” Goggins says. Much of the problem was the innate perishability of the asset in question. “If you think of 1830s or 1840s, if someone died in Edinburgh and their relatives lived in Glasgow, the idea of even getting the news to Glasgow that someone had died, then a relative being able to get back to Edinburgh within 48 hours is pretty tricky.”

The result was many unclaimed bodies ending up on the dissecting table that belonged mostly to individuals from some of society’s least privileged corners. There were occasional close calls: Goggins points out a ledger book by Professor Monro, which references a woman who died in an Edinburgh Hospital whose corpse was sold prematurely. “His note says ‘Her friends came to retrieve her body before she could be dissected…’” she says, adding: “I kind of think his handwriting looks cross.”

While it effectively ended bodysnatching, the Anatomy Act carried with it its own unsavoury air which, combined with the infamy of Burke and Hare and the London Burkers, made the public abhor it. To them it was as another attack on the poorer classes and unfortunates—for the benefit of academia, firmly in the echelons of society’s better-heeled. It ultimately made anatomy less of a spectacle and more a pursuit of quiet, almost secretive study for those that needed it.

Nearly 200 years later, that need is there still—but the attitude towards donation has changed completely.

The greatest gift

Today, death is in many ways more removed from view than ever—but for the public, anatomy’s uneasy blend of curiosity and voyeurism remains. This has been publicised in the activities of individuals such as performance anatomist Gunther von Hagens, and a few U.S. controversies that have blurred the boundaries of what is meant to donate your body for ‘medical research’.

“‘Burking’ became a kind of verb for smothering someone and selling their body for dissection.”

Scotland, meanwhile, has some of the strictest rules on body donation in the world, with specific institutions overseeing their own pledging programs. And when it comes to a new generation of students whose jobs will require them to handle death on a daily basis, those donations (all now given willingly) are performing a critical task.

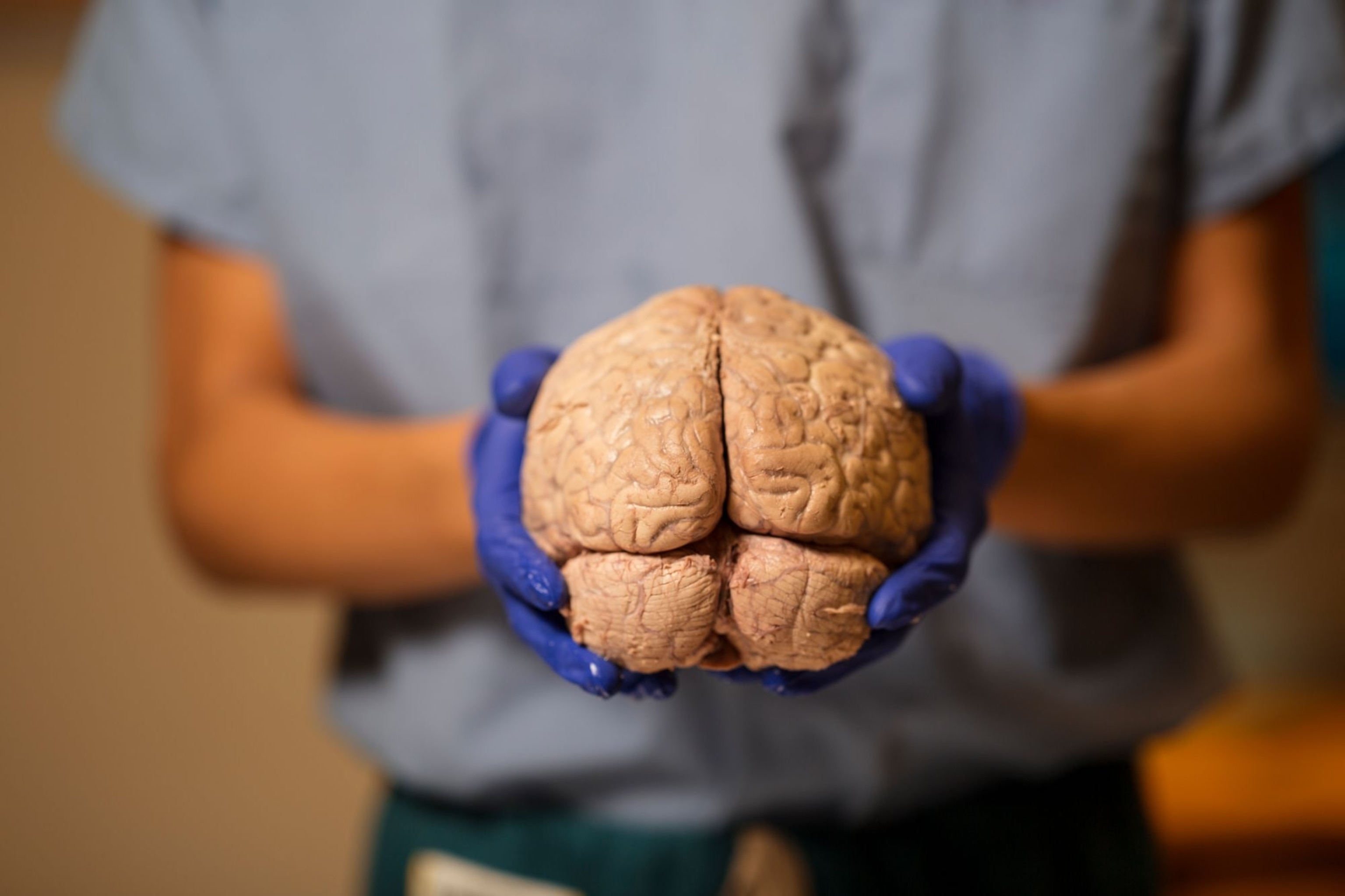

“The donors act as a bridge—a safe way to introduce people to [physical remains] in a culture that doesn’t address it openly,” says Tom Gillingwater. “When my medical students come in for their first class at university, one of the first things we do is introduce them to a cadaver, to one of our doners. And I ask the students, which of you has seen a dead body before? And very, very few of them have. It’s a watershed moment for them. A big deal, and not easy. And it means there’s a big gap between what people have experienced in their lives and what they may need to experience to fully understand the human body.”

Gillingwater describes the gauntlet of emotions some students traverse—‘anxiety, fear even’—around seeing a cadaver for the first time, but that these swiftly evaporate after the first class, giving way to curiosity and, he hopes, a reverence that crosses the mortal barrier.

“The act of learning from an individual—a body—I think acts as one of the biggest most important learning processes about dignity for the individual,” he says. “It teaches you to have respect for the patients—for the people you are engaging with— from the word go. It is the most intimate relationship you can imagine.”

Naturally, such close contact with a cadaver can cause shyness or reluctance to explore—something Gillingwater says is perhaps the opposite to what is needed. “We have to really tell the students is that these incredibly generous individuals wouldn’t be upset that you’re invading their personal space; they would be upset if you weren’t,” he says. “If you were not willing to engage with them—to not use their incredible gift—that would probably make them upset.”

Gillingwater adds: “What you need is for [students] to see the gift of the donor for what it is—a gift given essentially to them, to learn what things look like in a safe space, in their own time… so they can actually deal with these things as they move on in their career.”

A perspective on humanity

One piece in the exhibition perhaps symbolises the changing attitudes towards this most vital component of medical training. “We’re not meant to have favourites, but I love the Book of Remembrance,” says Sophie Goggins. Calligraphed by artist Annette Reed, the book “contains the names of everyone from the year 2000 who has donated their body to the University of Edinburgh’s donation program. It’s on display usually in the medical school for family members, so we’re really lucky to have it.”

There is also more insight to be gained from the procedure of anatomy than simply knowledge of our insides. Witnessing a dissection for his 2019 book The Body: A Guide for Occupants, upon being shown a peeled-back sliver of epidermis on a cadaver, author Bill Bryson was told by the attending professor the pigment in the millimetre-thick layer of skin represents “all that race is” biologically—along with every prejudice and grievous act it has spurred over the centuries. (Related: race and ethnicity, explained.)

“There is so much in the world that is based on the perceived notion of similarities or differences,” says Tom Gillingwater. “Yet when you get underneath the skin there are just as many differences between white Caucasian individuals, say, as there are between Caucasians and people from Africa or the Far East. And that diversity is beautiful.”

“None of us are the same. None of us look like a textbook. But we are all human,” he adds. “And how lucky we are to have been born.”

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- Charlotte, the 'virgin birth' stingray, has a diseaseCharlotte, the 'virgin birth' stingray, has a disease

- See how billions of cicadas are taking over the U.S. this summerSee how billions of cicadas are taking over the U.S. this summer

- Why are orcas ramming boats? They might just be bored teenagersWhy are orcas ramming boats? They might just be bored teenagers

- These pelicans are starving to death—despite plenty to eatThese pelicans are starving to death—despite plenty to eat

- The world's largest fish are vanishing without a traceThe world's largest fish are vanishing without a trace

Environment

- Exploring south-central Colorado’s backcountry

- Paid Content

Exploring south-central Colorado’s backcountry - 2024 hurricane season forecasted to be record-breaking year2024 hurricane season forecasted to be record-breaking year

- Connecting a new generation with South Africa’s iconic species

- Paid Content

Connecting a new generation with South Africa’s iconic species - These images will help you see coral reefs in a whole new wayThese images will help you see coral reefs in a whole new way

- What rising temps in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlifeWhat rising temps in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlife

- He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?

History & Culture

- Think customer service is bad now? Read this ancient complaintThink customer service is bad now? Read this ancient complaint

- The tragic backstory of one of the most haunted roads in AmericaThe tragic backstory of one of the most haunted roads in America

- The missing heiress at the center of New York’s oldest cold caseThe missing heiress at the center of New York’s oldest cold case

- When a people's stories are at risk, who steps in to save them?When a people's stories are at risk, who steps in to save them?

- I wrote this article with a 18th century quill. I recommend it.I wrote this article with a 18th century quill. I recommend it.

- Why this Bronze Age village became known as ‘Britain’s Pompeii’Why this Bronze Age village became known as ‘Britain’s Pompeii’

Science

- How being the oldest or youngest sibling shapes your personalityHow being the oldest or youngest sibling shapes your personality

- Tuberculosis is rising in the U.S. again. How did we get here?Tuberculosis is rising in the U.S. again. How did we get here?

- Are ultra-processed foods as addictive as cigarettes?Are ultra-processed foods as addictive as cigarettes?

- Epidurals may do more than relieve pain—they could save livesEpidurals may do more than relieve pain—they could save lives

Travel

- Exploring south-central Colorado’s backcountry

- Paid Content

Exploring south-central Colorado’s backcountry - What to eat in Lebanon, from flatbreads to layered dessertsWhat to eat in Lebanon, from flatbreads to layered desserts

- This sunny German city should top your summer travel list

- Paid Content

This sunny German city should top your summer travel list - 7 things you need to know about European travel this summer7 things you need to know about European travel this summer