Charles Town’s Growing Pains

Processing Request

Processing Request

Recently I was sitting in Council Chambers at Charleston’s City Hall, admiring the many historical paintings that adorn the dark, paneled walls, and my attention fixed on a marble slab that displays the names and dates of service for each of Charleston’s mayors. Over nearly 235 years of city government, there have been 61 different executives of City Council, some more memorable than others. At the top of this marble slab that caught my attention, there is a large, bold inscription of the following words: “City of Charleston. Founded 1670. Incorporated 1783.” This text got me thinking about the age of the city and trying to make sense of the arithmetic. In 2018, we can say that Charleston was founded 348 years ago, but the City of Charleston was incorporated 235 years ago. Since that time, the citizens of Charleston have witnessed the continuous activity of City Council, its ordinances, departments, and many colorful mayors. But what can we say about the first one hundred and thirteen years of Charleston’s existence, between 1670 and 1783? Is there a story to be told about the management or government of the town before it was incorporated? Of course there’s a story, and the surviving records of South Carolina’s colonial government provide the means for traveling back in time to that remote era.

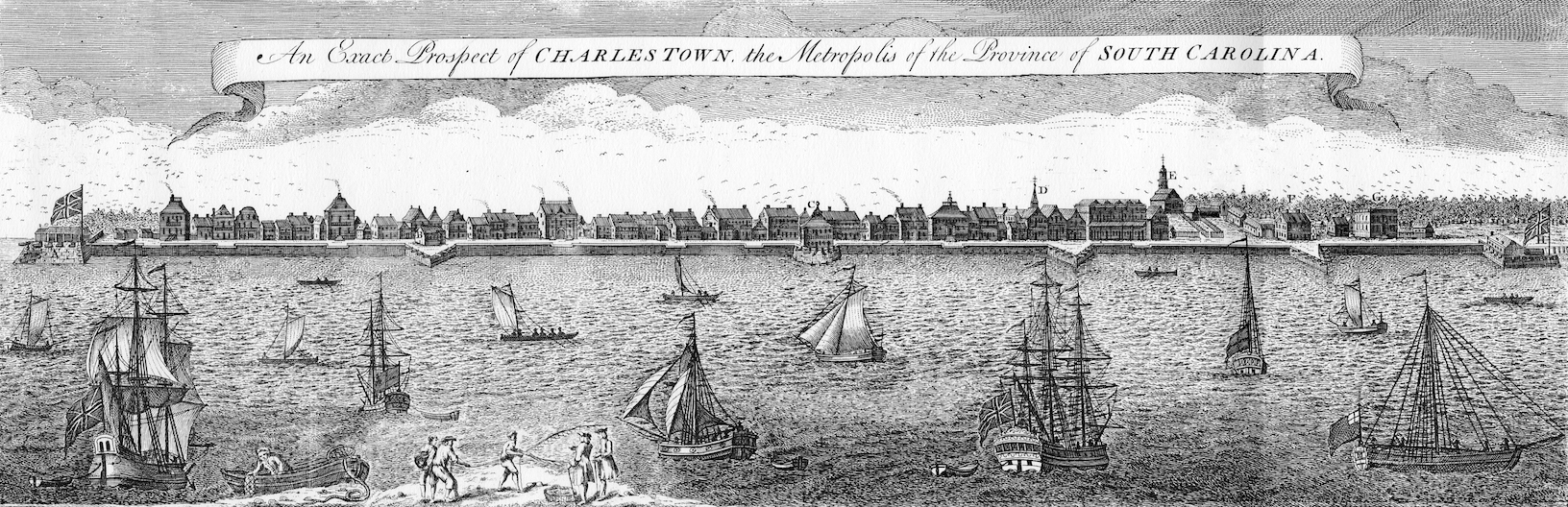

Charles Town was established in April 1670 by approximately 200 Europeans who settled at Albemarle Point, on the west bank of the Ashley River. This was the first settlement and the seat of government for the nascent colony of South Carolina. Ten years later, in 1680, the government and the name “Charles Town” moved to the opposite side of the Ashley River, to the peninsula formerly known as Oyster Point. Throughout the rest of our colonial period and the American Revolution, Charles Town remained South Carolina’s principal town and seaport, its seat of commerce and government, and its most densely populated community. Despite all of the social, political, and economic advantages that it enjoyed during the first one hundred and thirteen years of its existence, however, Charles Town was in some ways a defective entity: it lacked a municipal government.

To put the status of early Charles Town in the proper perspective, let’s think back to the way communities were organized in ancient England and in the early English colonies of North America. A village or hamlet or what-have-you, is a settlement comprised of multiple families living in close proximity and forming (to some degree) a self-sustaining community. If a superior legal entity, such as a monarch or a parliament or a legislative assembly, grants to such a settlement a charter (that is, legal permission) to hold a public market, then the settlement is raised to the level of a “market town.” A small town might have an informal system of self-government, while a larger town might have a more robust council of representatives elected by the local constituents. Regardless of its size, however, an English or early Anglo-American town is not incorporated; that is to say, it is not a corporation. To obtain corporate status, or to be incorporated as a “body politic,” one needs a grant or charter from a superior legal body that empowers the corporation to make its own laws and to levy and collect its own taxes. The city of London, for example, received its corporate charter in 1067. Other English cities usually achieved city status after constructing a cathedral. In North America, there were only handful of English cities. New Amsterdam (later New York), for example, received its city charter in 1653. The city of Philadelphia, founded in 1682, was incorporated in 1701. Annapolis, Maryland, was incorporated in 1708. From a legal perspective, nearly every other settlement on this continent was simply a village, a town, or a market town.

By the authority of the Lords Proprietors of Carolina, the first settlement in this colony was a market town named in honor of King Charles II of England. It remained unincorporated for one hundred and thirteen years, during which time the name Charles Town (or Charlestown) accurately reflected its inferior political status. Nowadays we tend to play fast and loose with this terminology, so you might hear people talk about “the colonial city of Charleston” or “the city fortifications of colonial Charleston” or the “city limits of colonial Charleston,” but, technically speaking, all of this nomenclature is inaccurate. For the entire colonial era, Charles Town was nothing more than an unincorporated market town with no independent system of municipal government. The Fundamental Constitutions of Carolina, written by the Lords Proprietors of the colony, ordered the creation of counties which were to be divided into precincts, each with its own courts and officers to serve the various settlements to be made in Carolina. In reality, however, the settlers established courts in Charles Town only and spent the rest of their energies developing rural plantations in the pursuit of personal profit. In this administrative respect, South Carolina diverged greatly from the English models followed by all of the colonies to the northward.

So, who was governing colonial Charles Town? From the founding of the colony of South Carolina in 1670 to the end of the American Revolution, the only form of government in urban Charles Town existed at the provincial level. Our first legislative body, styled the “Grand Council” of Carolina, was composed of locally-elected representatives and the appointed deputies of the Lords Proprietors in England. Their inaugural meeting took place at the original site of Charles Town on Albemarle Point in late August 1671. Nine years later, in the spring of 1680, the seat of government moved from Albemarle Point to the peninsula of land at the confluence of the Ashley and Cooper Rivers, where an unnamed town had been laid out a few years earlier. Shortly after that move, however, the South Carolina Parliament, as it was sometimes called, collapsed under the weight of several years of local mismanagement. A new legislative framework, created in the summer of 1692, proved to be more enduring. Composed of an elected lower house and an appointed upper house, this “general assembly” endured until 1776, when it was transformed into the present state government of South Carolina.

So, if the only form of government in early Charles Town was the provincial general assembly, to what extent did that body address the civil needs of the urban population? This is the question that I’ve been asking myself lately, as I pour over the notes I’ve collected from years of looking through the statute laws of early South Carolina and the manuscript journals of our colonial legislature. The answer is spread over a century’s worth of documentary evidence, but you won’t find it articulated in any published history of Charleston. This is still a work in progress for me, but I’d like to share my current thoughts on this important topic. I would humbly submit that the history of the administration of urban Charles Town prior to its incorporation in 1783 can be divided into five distinct phases: the early Proprietary era (1670–1695), the mature Proprietary era (1696–1721), the era of Charles City and Port (1722–1723), the Royal era (1730–1774), and the era of the American Revolution (1775–1782).

The Early Proprietary Era (1670–1695)

In the early decades of Charles Town’s existence, the population of the town (and of South Carolina in general) was quite small. From a group of approximately 200 settlers who arrived in 1670, the colony's population stood at approximately 5,000 souls in 1695, at which time there were roughly 1,000 people living in a few hundred houses on the peninsula of Charles Town. For all practical purposes, there was no public infrastructure in the town except for a handful of sandy streets and nearly 300 building lots staked out by the early surveyors. The scope of our provincial government was very limited, and, in return, the people expected very little from government. In the case of some sort of public necessity, such as a problem with wandering goats or a noisome cesspool, for example, the urban inhabitants, either individually or as groups of neighbors, shouldered the responsibility for effecting the solution. No one clamored for government intervention.

In the early decades of Charles Town’s existence, the population of the town (and of South Carolina in general) was quite small. From a group of approximately 200 settlers who arrived in 1670, the colony's population stood at approximately 5,000 souls in 1695, at which time there were roughly 1,000 people living in a few hundred houses on the peninsula of Charles Town. For all practical purposes, there was no public infrastructure in the town except for a handful of sandy streets and nearly 300 building lots staked out by the early surveyors. The scope of our provincial government was very limited, and, in return, the people expected very little from government. In the case of some sort of public necessity, such as a problem with wandering goats or a noisome cesspool, for example, the urban inhabitants, either individually or as groups of neighbors, shouldered the responsibility for effecting the solution. No one clamored for government intervention.

During the first twenty five years of South Carolina’s existence, the only measure undertaken by the provincial legislature to address the specific needs of Charles Town was the creation and maintenance of an urban night watch. Commencing in October 1671, the Grand Council of Carolina ordered the provincial marshal to make a list of freeholders living in the town and to summon a rotating portion of them each night to guard the streets and to deliver any malefactors to a magistrate in the morning. This practice was formalized into statute law in April 1685, and the provincial legislature continued to supervise the activities of the Charles Town Watch until the autumn of 1783, when it became the City Guard, the precursor of the modern Charleston Police Department.

The Mature Proprietary Era (1696–1721)

In late 1694, the Lords Proprietors of Carolina gave to the newly-appointed governor, John Archdale, permission to request a charter for the incorporation of Charles Town, “if you think it convenient for ye promotion of good Government to check vice and Incourage Sobriety and vertue as well as trade.” Governor Archdale arrived in Charles Town in August 1695 and returned to England at the end of 1696 after having succeeded in quieting the colony’s factional political atmosphere. Despite the important political stability John Archdale brought to South Carolina in the final years of the seventeenth century, he did not pursue the incorporation of its capital and its approximately 1,000 inhabitants. Nevertheless, whether by coincidence or by design, the provincial assembly during Governor Archdale’s brief administration instituted one small but significant change in their legislative strategy that would have important ramifications for the future of urban Charles Town.

Starting in March 1695/6 and continuing through the 1720s, the South Carolina legislature ratified a number of statutes that appointed temporary boards of commissioners to supervise the execution a number of urban tasks authorized by specific laws, such as caring for the poor and orphans, clearing town lots, removing nuisances, creating sidewalks, constructing and repairing fortifications, inspecting chimneys, and procuring and maintaining fire buckets, fire-hooks, and ladders. This legislative innovation was a far cry from a perpetual system of municipal self-governance, but the advent of commissioners empowered to execute specific urban tasks was an important small step in the direction of a separate municipal government.

Starting in March 1695/6 and continuing through the 1720s, the South Carolina legislature ratified a number of statutes that appointed temporary boards of commissioners to supervise the execution a number of urban tasks authorized by specific laws, such as caring for the poor and orphans, clearing town lots, removing nuisances, creating sidewalks, constructing and repairing fortifications, inspecting chimneys, and procuring and maintaining fire buckets, fire-hooks, and ladders. This legislative innovation was a far cry from a perpetual system of municipal self-governance, but the advent of commissioners empowered to execute specific urban tasks was an important small step in the direction of a separate municipal government.

Charles City and Port (1722–1723)

After enduring several years of internal strife and general decline, the leading inhabitants of Charles Town staged a bloodless political coup in December 1719 to displace the authority of the absentee Lords Proprietors of Carolina. The rebels created their own temporary government and appealed to King George I to assume control of the failing colony. Provisional Royal Governor Francis Nicholson arrived in Charles Town in late May 1721 and embarked on a four-year effort to steer South Carolina back to the path of success. An experienced administrator at the end of a long political career, Governor Nicholson immediately urged the General Assembly to consider incorporating urban Charles Town (with a population of nearly 3,000 souls). After much political wrangling, on 23 June 1722 the legislature ratified an act to incorporate the capital under the name of “Charles City and Port,” with a mayor presiding over a bicameral municipal government composed of a council of aldermen and a “common council.” The form and content of this law did not sit well with British authorities, however, and this act of incorporation was disallowed in June 1723. News of this reversal arrived in South Carolina nearly five months later, and “Charles City and Port” quietly reverted to unincorporated “Charles Town” in early October 1723. No records of this short-lived municipal government are known to survive.

The Royal Era (1730–1774)

King George II formally completed the purchase of South Carolina from the Lords Proprietors in 1729, and the “Royal” government of this colony officially commenced in 1730. In the ensuing years, the Royal oversight and management of South Carolina contributed greatly to the stability and credit of this once-foundering colony. There were signs of success throughout the 1730s. Trade and shipping increased, immigrants arrived in greater numbers than ever before, a newspaper was established in Charles Town, and a general sense of optimism prevailed. At the same time, the inhabitants of the urban capital, numbering just over 4,000 free whites and enslaved Africans by the mid-1730s, began demanding greater attention from the provincial legislature. In response, the South Carolina General Assembly embarked on a new method of addressing their perennial complaints. Rather than appointing commissioners on an ad hoc basis, as it had done in the past, the legislature ratified a series of six laws that created several permanent, standing commissions to superintend matters that were crucial to the prosperity and common weal of urban Charles Town.

First, on 9 April 1734, the legislature created a board of commissioners of the pilotage for Charles Town harbor. Next, on 29 May 1736, the South Carolina General Assembly ratified four acts for that created boards of commissioners to superintend the town’s markets, its fire masters, its work house and urban poor, and its urban fortifications. Finally, on 31 May 1750, the legislature passed an act creating the Commissioners of Streets in Charles Town, who were empowered to hire scavengers to begin the tradition of weekly curbside garbage collection. From their creation in the 1730s until the American Revolution, the commissioners of pilotage and fortifications were appointed by the governor, while the remaining commissioners were elected annually by popular vote on Easter Mondays at St. Philip’s Church. Collectively, these six acts represent a major step forward in the government of urban Charles Town, but historians of the city don’t seem to have recognized their importance. Perhaps that’s because all of the six aforementioned acts appointing commissioners for the management of urban Charles Town were omitted from the published compilation of the Statutes at Large of South Carolina that was published under the auspices of the state government in the late 1830s and early 1840s. The original engrossed manuscript laws survive among the vast collections of the South Carolina Department of Archives and History in Columbia, but few historians have taken the time to look for them.

Following the conclusion of the French and Indian War in 1763, South Carolina and the American colonies in general experienced a wave of prosperity and expansion. Here in urban Charles Town, the population swelled to approximately 11,000 souls by the late 1760s. The increasingly dense population precipitated a growing chorus of complaints about unchecked misdemeanors such as unjust market practices, vice, drunkenness, profanity, and Sabbath-breaking. The surviving newspapers of pre-Revolutionary Charles Town contain a number of letters pleading for the incorporation of the town as a means of addressing the neglected infrastructure and social chaos of the urban environment. In August 1769, the South Carolina legislature passed a law moving the town boundary northward in order to annex the suburbs of Ansonborough and Harleston. That same month, a grand jury recommended the ratification of a law to incorporate Charles Town, “whereby the Inhabitants thereof and the Public in General may be relieved from any inconveniences which they labour under.” The Commons House of Assembly ordered a bill to be drafted accordingly, but it never materialized. A similar grand jury presentment in January 1770 also went unheeded. A newspaper editorial in November 1772 pleaded again for a law incorporating Charles Town, “for the people of that place, forming, as it were, a distinct community from the other inhabitants of this province, certain regulations are necessary for their intestine government.” The final colonial-era plea for incorporation came in June 1774, when a grand jury sitting in Charles Town “most earnestly” recommended “that the Legislature may pass an Act for incorporating this Town, as the only Means that will effectually remove many Enormities, remove and redress many Grievances, and tend to introduce and establish many wise and beneficial regulations.” Again, there was no response from the legislature, and by 1775 the increasingly strained relationship between England and her American colonies pushed all other matters to the periphery of local political debates.

Following the conclusion of the French and Indian War in 1763, South Carolina and the American colonies in general experienced a wave of prosperity and expansion. Here in urban Charles Town, the population swelled to approximately 11,000 souls by the late 1760s. The increasingly dense population precipitated a growing chorus of complaints about unchecked misdemeanors such as unjust market practices, vice, drunkenness, profanity, and Sabbath-breaking. The surviving newspapers of pre-Revolutionary Charles Town contain a number of letters pleading for the incorporation of the town as a means of addressing the neglected infrastructure and social chaos of the urban environment. In August 1769, the South Carolina legislature passed a law moving the town boundary northward in order to annex the suburbs of Ansonborough and Harleston. That same month, a grand jury recommended the ratification of a law to incorporate Charles Town, “whereby the Inhabitants thereof and the Public in General may be relieved from any inconveniences which they labour under.” The Commons House of Assembly ordered a bill to be drafted accordingly, but it never materialized. A similar grand jury presentment in January 1770 also went unheeded. A newspaper editorial in November 1772 pleaded again for a law incorporating Charles Town, “for the people of that place, forming, as it were, a distinct community from the other inhabitants of this province, certain regulations are necessary for their intestine government.” The final colonial-era plea for incorporation came in June 1774, when a grand jury sitting in Charles Town “most earnestly” recommended “that the Legislature may pass an Act for incorporating this Town, as the only Means that will effectually remove many Enormities, remove and redress many Grievances, and tend to introduce and establish many wise and beneficial regulations.” Again, there was no response from the legislature, and by 1775 the increasingly strained relationship between England and her American colonies pushed all other matters to the periphery of local political debates.

The Revolutionary Era (1775–1782)

During the early years of the American Revolution, from 1775 through the spring of 1780, Charles Town was a bustling hive of military activity. The rebellious provincial government, which morphed into a sovereign state government in March 1776, supervised the construction, repair, and expansion of fortifications around the town during the early years of the Revolution. With the exception of the town’s traditional night watch, which was temporarily transformed into an more robust military patrol, however, the state government largely ignored the town’s civic needs for the duration of the war. In the summer of 1778, for example, Massachusetts native Benjamin West described Charles Town in a letter to his brother. After noting the town’s robust urban fortifications, West remarked with a distinct air of condescension, “as for police [by which he meant a civil government], they have none, nor have they any town or city officers whatever of any denomination.” One might argue, in defense of the southern sea port, that the timing of West’s visit to Charles Town coincided with a general state of emergency, but the fact remains that the town’s lack of municipal government stood in stark contrast with the more mature civic traditions of colonial New England.

After a protracted siege lasting nearly two months, the American and French forces defending Charles Town surrendered the town to the British on 12 May 1780. During the ensuing two years, seven months, and two days, British forces imposed martial law over the town, which served as the base for their military operations throughout South Carolina. To administer the town’s civic needs, the occupying force instituted a “Board of Police” with jurisdiction over non-military issues such as maintaining public cemeteries and public wells, adjudicating misdemeanor offenses and the collection of small debts, and regulating the assize of bread. The story of British soldiers using the basement of the Old Exchange Building as a military prison or “provost dungeon” is familiar to most Charlestonians and visitors, but the role of the Board of Police, and its headquarters in Craven Bastion (a large, brick fortification now under the U.S. Custom House near the east end of Market Street), has received far less attention. The wartime activities of this paramilitary board seem to have had little permanent impact on the subsequent municipal history of Charleston, with one small exception. In the summer of 1780, shortly after capturing the town, the British Board of Police initiated the task of assigning street numbers to the houses and buildings of urban Charles Town. We can imagine that the conquering forces were frustrated, perhaps even flabbergasted, by the disorder that reigned in the crowded, unincorporated town, and felt grudgingly obliged to impose a modicum of logic on the landscape. Their numbering system, which began at the town’s northern boundary and moved southward, represents the first step toward the city’s present system of street addresses (which run from south to north).

The Incorporation of Charleston in 1783

Following the evacuation of the last British forces from the town on 14 December 1782, South Carolina’s state government convened in Charles Town in January 1783 and began the long and arduous task of restoring order after nearly eight years of war. The jurisdiction of their efforts included more than 200,000 citizens spread across a war-torn landscape of more than 32,000 square miles. With the exception of a handful of local representatives, the majority of the men who comprised South Carolina’s General Assembly had little inclination to spend valuable time addressing the local needs of the state’s unincorporated capital with its population of approximately 12,000 souls. In response to this legislative apathy, on 4 August 1783, the elected representatives of the urban parishes of St. Philip and St. Michael introduced a bill to incorporate Charles Town. Following the customary three readings and debates of the bill, the General Assembly ratified “An Act to Incorporate Charleston” nine days later, on 13 August 1783. The preamble to the act offers a succinct rationalization behind this historic move toward municipal government:

“Whereas, from the extent and population of Charlestown, its growing importance, both with respect to increase of inhabitants and an extensive commerce with foreign nations, it is indispensably necessary that many regulations should be made for the preservation of peace and good order within the same: and whereas from the many weighty and important matters that occupy the attention of the Legislature at their general meeting, it has hitherto been found impracticable, and probably may hereafter become more so, for them to devise, consider, deliberate on, and determine, all such laws and regulations, as emergencies, or the local circumstances of the said Town, may from time to time require.”

“Therefore be it enacted, by the honorable the Senate and House of Representatives, and by the authority of the same, that from and immediately after the passing of this act, all persons, citizens of the United States, and residing one year within the said town, or having had a freehold one year within the same, shall be deemed, and they are hereby declared to be, a body politic and corporate; and the said Town shall hereafter be called and known by the name of the city of Charleston.”

I’ll save the details of Charleston’s new civil structure for a future conversation, but I’ll mention one important fact to conclude this colonial-era discussion. The 1783 act of incorporation specifies that the several colonial-era boards of commissioners, created by the provincial legislature between 1734 and 1750, and the various laws associated with their activities, were to be vested and continued under the jurisdiction of the new City Council of Charleston. That is to say, in 1783 (and by a supplemental law in 1784), Charleston’s new municipal government absorbed the powers and duties of the old and well-established commissioners of the pilotage, the commissioners of the market, the commissioners of the work-house, the board of fire-masters, the commissioners of fortifications, and the commissioners of the streets.

In short, the advent of Charleston’s municipal government in 1783 was not simply the act of creating of new political entity in a metaphorical municipal vacuum. Rather, the incorporation of the City of Charleston in 1783 was the culmination of social and political circumstances that had evolved by degrees over a period of one hundred and thirteen years. The City Council of Charleston, composed of a board of aldermen with the power to ordain laws and to levy taxes over an urban body politic, was indeed a new phenomenon in the history of South Carolina in 1783, but it was established on the foundation of an experienced and functional political mechanism that had existed for nearly half a century.

I’m not suggesting that this information changes the “story” of the City of Charleston in any way. But I hope you’ll agree that this information sheds new light on the background behind the city’ government that enriches the narrative of its history, and helps us to appreciate the lives of the people who walked these streets long before we came along.

PREVIOUS: The South Carolina Constitutional Convention of 1868

NEXT: James Hoban’s Charleston Home

See more from Charleston Time Machine

- Log in to post comments