Last week, a trailer for The Mummy hit the internet – a strange, disjointed, shabby-looking affair, promising little in the way of reason for re-exhuming this fusty franchise of Egypto-crypto-mysticism, and made stranger still by the presence of Tom Cruise. There he is, still lean and limber at 54, clinging for dear life to a plummeting aircraft, tumbling sideways through the windshield of a London double-decker, acing a gruelling triathlon of running, swimming and grimacing. For all his physical capability and credibility, he seems out of place: why is a supernova like Cruise consenting to something this secondhand, something in which he seems so replaceable? Cruise is the kind of star around whom films are shaped, even ones as anonymous as Jack Reacher: Never Go Back. The Mummy, on the other hand, looks like one in which he was inserted.

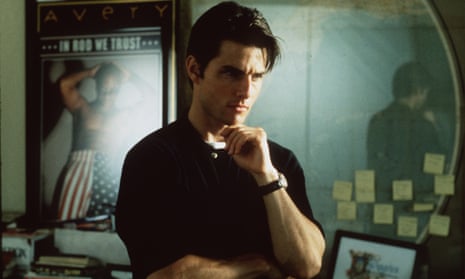

Twenty years ago this week, Cameron Crowe’s Jerry Maguire arrived in US cinemas – and at that moment in time, the prospect of Cruise lending his name to something as low-rent as The Mummy might have seemed a little outlandish. Given an extra veneer of prestige by its awards-season release date and its imposing 140-minute length, Crowe’s high-class romantic comedy wasn’t exactly a comeback vehicle for its 34-year-old leading man, who was still fresh from a profitable summer bout of ass-kicking in Brian De Palma’s Mission: Impossible. But it nonetheless seemed to announce a second, more self-aware phase of his career – one that admitted some cracks beneath the spotless, flashily grinning facade.

He may have made his grand declaration of Serious Actor intentions seven years previously in Oliver Stone’s Born on the Fourth of July, and befuddled some fans with his chilly, affected Lestat in Interview With the Vampire, but those were active, effortful, only debatably successful steps outside his star persona. Jerry Maguire, on the other hand, cannily sanded down the sharp corners of that persona, exposing more boyish weakness than boyish bravado in that all-American image. Crowe’s film told the story of a glib, margarine-slick sports agent brought around to the more important things in life by sudden failure and the love of a good woman; it was a redemption tale that sought to humanize its star in the eyes of viewers who still saw him as the unsinkable Maverick Mitchell.

Previous attempts to cast Cruise as a principally romantic lead – notably the drippy Blarney of Ron Howard’s Far and Away – had fit him like a three-fingered glove. That was partly because they didn’t admit to his impenetrability, the fact that beneath that million-dollar smile (or perhaps because of it), he comes off onscreen as, well, a little bit of a dick. His Jerry, however, presents a suitable case for treatment, an outwardly pristine man in need of some internal repair.

“I love him for the man that he almost is,” simpers Dorothy, the kindly bookkeeper and single mother who improbably snags Jerry Maguire’s semifreddo heart after he’s let go from his high-powered sports agency. She is played, of course, by the then unfamiliar but immediately lovable Renee Zellweger, whose genial, jeans-and-sweater beauty was hailed at the time as an antidote to the glassier sex symbols one might have expected to see opposite Cruise. (Like, say, Kelly Preston, none too flatteringly cast as Maguire’s venal fiancee at the outset.) Hers was the perfect image to set Cruise’s in relief: “You complete me,” he tells her later, concluding a long, macho-florid monologue in which he nobly cops to a litany of emotional weaknesses.

Crowe’s endlessly sympathetic screenplay doesn’t punish Maguire any further as it rushes to its warm hug of a denouement: confession is essentially cure in this Hollywood therapy session. (Is he now the man he once almost was?) Still, it was startling to see Cruise unfold and admit this much: striking enough to make Jerry Maguire a smash well beyond his existing fanbase, and earn him a second Oscar nomination for best actor. The film itself earned four more, including one for best picture alongside The English Patient, Fargo, Secrets and Lies and Shine – making it the big studios’ prize pony in an awards season otherwise branded “the year of the indies”.

Brash and shiny and fleet even at its needless length, accessorized in scene after scene with chunky cellphones and wraparound sunglasses – it’s as tidy a 1996 time capsule as Trainspotting is a disorderly one – Jerry Maguire was a studio film through and through. Yet Crowe clearly conceived it as one with an independent heart. Just as Maguire’s stream-of-consciousness professional manifesto, conceived near the beginning of the film as his first symptom of nascent maturity, advocates prioritizing people over big business, so Crowe’s film pointedly uses the luxuries of Hollywood artifice – the aura of Tom Cruise among them – to celebrate the virtues of the real. “Show me the money,” as instructed by Maguire’s most loyal client, mouthy middle-of-the-pack footballer Rod (an Oscar-winning Cuba Gooding Jr), may be the most indelibly quotable line in a film of many, but Maguire predictably saves himself by setting such priorities aside.

Well, sort of. Jerry Maguire may retain a considerable measure of its easy-breezy Coors Light charm, but 20 years on, its more cautious compromises stand out. Just what exactly does its hero lose to win? Maguire begins and ends the film a sleek, successful wheeler-dealer; money and celebrity remain the tenets of his professional life, even if he’s gained a doting wife and stepson on the path from riches to riches. (Even his moments of self-criticism pale beside Dorothy’s, who peculiarly blames herself for snaring him in the obligatory second-act crisis of their relationship; Jerry Maguire may seem to progressively serve a female audience under the cloak of a brawny sports movie, but its understanding of women is entirely masculine.) Crowe’s well-meaning script nods to gender equality and even racial prejudice in its glossy world – “I’m Mr Black People!” Maguire gauchely brags to Rod, though the film’s portrait of the latter, however jubilantly performed by Gooding, itself skirts crass African American caricature.

Jerry Maguire’s brilliant-white male hero thus learns a lesson in humility without ever having the focus pulled from him. Or, indeed, from Cruise, who has since probed the scratched underside of his stainless-steel star image in such projects as Magnolia and Rock of Ages – while somehow remaining every inch the alpha throughout. Even that playful curiosity seems to have waned in latter-day vehicles such as The Mummy, Jack Reacher and the umpteenth Mission: Impossible retread: the latest phase of Cruise’s career seems to have recast him as an invulnerable, unknowable action figurine of himself. Perhaps the time has come for Crowe – himself adrift in the wake of multiple touchy-feely misfires like Aloha – to snuggle up to him once more.

Comments (…)

Sign in or create your Guardian account to join the discussion