Parenting

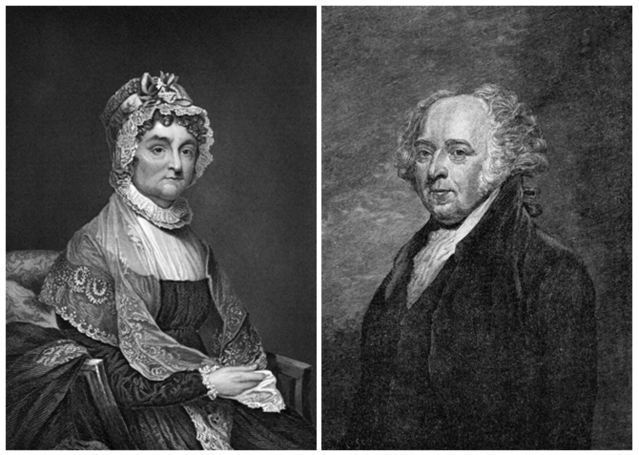

The Truth About John and Abigail Adams as Parents

Should 18th-century parenting be judged by 21st century standards?

Posted November 5, 2020 Reviewed by Hara Estroff Marano

THE BASICS

Being a parent is hard, no matter what era you're raising kids in. But having your parenting decisions looked down on for generations to come makes the job harder still.

President John Adams and First Lady Abigail are examples of what happens when eighteenth-century parenting is judged by twenty-first century standards.

Despite their being two of the most significant figures of the 1700s—John's biographer calls him “one of the most important Americans who ever lived,” and Abigail's biographer calls her "the most illustrious woman of the founding era"—both parents have been on the receiving end of much ridicule in modern times.

The Broadway smash Hamilton, for instance, teases that John only spent time with his family because “he doesn’t have a real job,” and HBO’s John Adams portrays an out-of-context dwindling relationship between John and Abigail and their alcoholic middle son, Charles.

"History has been unkind to John and Abigail Adams as parents," says Dr. Edith Gelles, a senior scholar at Stanford University's Clayman Institute and the author of multiple Adams family books and biographies.

What's more, some journalists have also sought to apply present-day terms to eighteenth century forms of child-rearing. A 2016 article in The Wall Street Journal, for example, accuses John of being a "Tiger Dad" and says his parenting style "makes modern tiger moms look like toothless tabbies." A similar article in The Los Angeles Times says that John was an "autocrat both at home and in the Oval Office."

Though such expressions might seem fitting, Gelles say they may not be accurate. "Parenting styles of that era cannot be understood by contemporary measures," she says. "It’s too simplistic to label with twenty-first century manners the development of children of that vastly different time."

While some of their parenting choices appear extreme to us today—John requiring his sons to translate Thucydides by age 10 or Abigail telling one of her children that she would rather he meet an "untimely death at the bottom of the ocean" than see him become "an immoral profligate—John and Abigail's treatment of their children was not uncommon for their day. "The Adamses' approach to parenting was well within the cultural and historical framework of their time," explains Gelles. "They were strict and also affectionate."

Indeed, in his book The Protestant Temperament, early American historian Dr. Philip Greven compares the parenting decisions of John and Abigail to their contemporaries and calls them "moderates" of their time. He writes that "moderates shared the conviction that legitimate authority—parental as well as other kinds—was limited, that human nature was sinful but not altogether corrupted, that reason ought to govern the passions, that a well-governed self was temperate and balanced, and that religious piety ought to be infused with a concern for good and virtuous behavior."

Though thus tempered in his approach, John nonetheless had to do much of his parenting from afar. While assuming many of the diplomatic responsibilities of the American revolution, John was absent from the household for nearly ten years and missed long periods of his children's upbringing. His youngest son, Thomas, was born only two years into the Revolutionary War and "hardly knew his father personally, except for brief periods and by reputation until he was about eight," Gelles says.

THE BASICS

In John's absence, Abigail alone shouldered nearly every burden of raising their family along with tending to their home and farm. "Theirs was not a typical home life," Gelles says. "These were no ordinary times, but a massive upheaval in their household, their town, their colony and their nation."

In the midst of such upheaval, Abigail made mistakes. "She was imperfect," says Dr. Woody Holton, a professor of history at the University of South Carolina and the author of Abigail Adams: A Life. For one thing, Abigail and John intervened in two of their children's initial attempts at marriage. "They talked two of their four kids, (John Quincy and Abigail Jr. or "Nabby") from marrying the person they truly loved—and both ended up marrying other people, in neither case very successfully," Holton says. Nabby's was a classic case of a parent (John, in this case) not approving of a potential suitor for their child, but John Quincy's situation was more complicated.

John Quincy had fallen in love with a woman named Mary Frazier while still dependent on his parents for financial support. His mother was worried about his ability to provide for a new family before he'd established his law practice and advised him to "never form connections until you see a prospect of supporting a family." Her discouragements were enough for John Quincy to delay a public engagement, something Mary didn't want to put off. The relationship ended as a result and years later John Quincy married Louisa Catherine instead. "John Quincy was candid, even with Louisa, about not loving her, at least not like he had loved Mary Frazier," Holton says.

Parenting Essential Reads

Holton also notes that where John and Abigail may have been especially strict with John Quincy, they were likely too soft on Charles, their middle son, whose alcoholism led to his early death at age 30. "Obviously his parents weren't primarily at fault, but I think by coddling him, they played a role," Holton says. Of Diana Baumrind's four parenting styles (authoritarian, authoritative, permissive, and uninvolved,) Holton agrees that it's difficult to measure by modern standards but says that "Abigail was likely authoritative with John Quincy and permissive with Charles."

Religion and duty also played a major factor in the Adams household. "The major theme in all of my work has been an emphasis on the Adams family commitment to duty," Gelles says. Like Graven, Gelles explains that religious beliefs contributed greatly to how both parents raised their children.

"The Adamses lived in an era when religion was very much alive in their daily lives, both consciously and unconsciously," she says. As a result, the Adams family children were taught to consider the morality or righteousness in nearly every choice they made, including in matters of education, profession, marriage, and even politics. "Grace, or the condition of being acceptable in this life and prepared for the next, was of primary concern," Gelles explains. "Children were trained to behave in such a manner as to achieve grace."

And John and Abigail didn't always see eye to eye on every parenting decision. The senior Adams, for instance, wanted John Quincy to become president someday, once writing to his namesake: "If you do not rise to the head not only of your own profession, but of your country, it will be owing to your own laziness, slovenliness and obstinacy." Abigail, by contrast, wanted no such thing for her oldest, once declaring that she would rather see her son “a log thrown on the fire” than see him become president. Besides such anomalies, Gelles says that both parents usually agreed about "the standards they established for their children."

Gelles has studied and taught about the Adams family for more than 40 years and she oversaw the editing and inclusion of all 2,318 of Abigail's family letters for the Library of America. She says those letters are key to understanding the context of many Adams family decisions and that the childhoods of each of the four children "are visible to us today mostly through the family correspondence."

"I've read all of those letters through carefully many times," she says. In doing so Gelles has drawn a number of conclusions, one of which is especially worth noting: "I think John and Abigail Adams were excellent parents."