Object relations theory in psychoanalysis posits that early childhood relationships with primary caregivers, particularly the mother, profoundly shape an individual’s later interactions and emotional development.

It emphasizes internalized mental representations of self and others, which guide interpersonal relations and influence one’s sense of self-worth and attachment styles.

Klein’s (1921) theory of the unconscious focused on the relationship between the mother–infant rather than the father–infant one, and inspired the central concepts of the Object Relations School within psychoanalysis. Klein stressed the importance of the first 4 or 6 months after birth.

Object relations theory is a variation of psychoanalytic theory, which places less emphasis on biological-based drives (such as the id) and more importance on consistent patterns of interpersonal relationships.

For example, stressing the intimacy and nurturing of the mother.

Object relations theorists generally see human contact and the need to form relationships – not sexual pleasure – as the prime motivation for human behavior and personality development.

In the context of object relations theory, the term “objects” refers not to inanimate entities but to significant others with whom an individual relates, usually one’s mother, father, or primary caregiver.

In some cases, the term object may also be used to refer to a part of a person, such as a mother’s breast, or to the mental representations of significant others.

Developing a Theory of Unconscious Phantasy

Klein’s (1923) theory of the unconscious is based on the phantasy life of the infant from birth. Her ideas elucidated how infants processed their anxieties around feeding and relating to others as objects and part-objects.

These fantasies are psychic representations of unconscious id instincts; they should not be confused with the conscious fantasies of older children and adults.

She developed her theories largely from her work analyzing young children as a member of the Berlin Psychoanalytical Society, using toys and role play. Through close observation, she was able to interpret the dynamic inner workings of their minds.

The children, she believed, projected their anxieties about the part-objects of their parents – the breast, the penis, the unborn babies in the mother’s stomach – onto their toys and drawings. They would act out their own aggressive phantasies but also their desire for reparation through play.

When she wrote of the dynamic fantasy life of infants, she did not suggest that neonates could put thoughts into words. She simply meant that they possess unconscious images of “good” and “bad.” for example, a full stomach is good, an empty one is bad. Thus, Klein would say that infants who fall asleep while sucking on their fingers are fantasizing about having their mother’s good breast inside themselves.

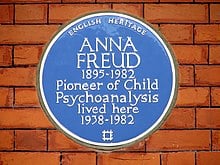

Unlike Anna Freud, who also worked with children, Klein felt that young children could bear the full weight of her analytical interpretations so she did not hold back or sugar-coat them (see her famous case study Narrative of a Child Analysis, 1961). She also observed that when a child was given the freedom to express his or her phantasies, which were then interpreted, their anxiety decreased.

Through analyzing young children, Klein felt she was able to discover vital developmental stages missed by her peers who only analyzed adults.

The Paranoid-Schizoid Position

Klein (1946) called the developmental stage of the first four to six months the paranoid-schizoid position. Rooted in primal phantasy, Klein’s infant is far darker and more persecuted than the Freudian pleasure-seeking narcissist.

Indeed, while Freudian drive theory sprung from his Life Instinct (Eros), Klein’s theories grew from her focus on the Death Instinct (Thanatos), which Freud himself never fully explored.

Klein believed that ego formation begins from the moment of birth when the newborn attempts to relate to the world through part-objects – thus the object ‘mother’ becomes a part-object ‘breast’.

Splitting

Central to object relations theory is the notion of splitting, which can be described as the mental separation of objects into “good” and “bad” parts and the subsequent repression of the “bad,” or anxiety-provoking, aspects (Klein, 1932; 1935).

Infants first experience splitting in their relationship with the primary caregiver: The caregiver is “good” when all the infant’s needs are satisfied and “bad” when they are not.

Splitting occurs when a person (especially a child) can’t keep two contradictory thoughts or feelings in mind at the same time, keep the conflicting feelings apart and focuses on just one of them.

The Kleinian baby must deal with immense anxiety arising from the trauma of birth, hunger, and frustration. The baby, in his phantasy, splits the mother’s breast into the Good Breast which feeds and nourishes, and the Bad Breast which withholds and persecutes the baby.

Splitting as a defense is a way of managing anxiety by protecting the ego from negative emotions. It is often employed in trauma, where a split-off part holds the unbearable feelings.

Klein wrote that ‘The Ego is incapable of splitting the object – internal and external – without a corresponding splitting taking place within the Ego… The more sadism prevails in the process of incorporating the object, and the more the object is felt to be in pieces, the more the Ego is in danger of being split’ (Klein, 1946).

The baby internalizes or introjects the objects – literally by swallowing the nourishing breast milk, symbol of life and love, but also though experiencing hunger pains and its own aggressive anger against the withholding Bad Breast inside its body. These internalized introjects or images form the basis of the baby’s ego.

The infant’s unconscious works to keep the Good Breast (and all it symbolizes; love, the life instinct) safe from the Bad Breast (feelings of hate and aggression, the death instinct). Thus, the paranoid-schizoid defense mechanism is set in motion.

The unconscious process of splitting, projection and introjection is an attempt to ease paranoid anxieties of persecution, internally and externally. Unbearable negative feelings as well as positive loving emotions are projected onto external objects, as in Freud.

In later life, we see the same process in adults projecting their unwanted fears and hatred onto other people, resulting in racism, war and genocide. We also see it when people employ positive thinking or conversely negative biases, seeing only what they want to see in order to feel happy and safe.

Projective Identification

Projective Identification is a psychic defense mechanism in which infants split off unacceptable parts of themselves, project them onto another object, and finally introject them back into themselves in a changed of distorted form.

By taking the object back into themselves, infants feel that they have become like that objects, that is, they identify with that object.

Projective Identification takes projection one stage further. Rather than projecting unwanted split-off parts onto the object as though onto a blank screen, then either idealizing them or feeling persecuted, Projective

Identification is the phantasy of projecting a part of oneself into the other person or object. The split-off parts become phantasized as having taken possession of the mother’s body and she becomes identified with them.

Unlike projection, in Projective Identification there is a blurring of boundaries. The object being projected into (e.g. the mother) is an extension of the baby, therefore in his omnipotent phantasy, it can be controlled by him.

And indeed, through subtle manipulations, the recipient can be made to feel and act in accordance with the projective phantasy. The infant, through various behaviors, can make his carer experience his frustration.

Klein’s (1946) concept of Projective Identification is credited with widening the notion of countertransference, particularly through the work of Bion.

Yet, despite planting the seed, Klein remained skeptical about countertransference, believing it interfered with therapy. If you have feelings about your patient, she said, you should do an immediate self-analysis (Grosskuth, 1987).

The Depressive Position

Melanie Klein first wrote about the Depressive Position in 1935. It is a term that she uses to describe the developmental stage that occurs in an infant’s first year, after the primal Paranoid-Schizoid Position.

She called these two states of mind ‘positions’ rather than ‘stages’, because she said that they are not stages we progress through, but positions, or ways of being, that we oscillate between throughout development and into adult life.

The Depressive Position first manifests during weaning – around three to six months – when a child comes to terms with the reality of the world and its

place in it.

At the heart of the Depressive Position is loss and mourning: mourning the separation of self from the mother, mourning the loss of the narcissistic phantasy where the child’s Ego was the world, mourning the objects it has hurt or destroyed through aggression and envy. But from the ruins, there arises first the feeling of guilt, then the drive for reparation and love.

In the Depressive Position, a child learns to relate to their objects in a completely new way. It has less need for splitting, introjection, and projection as defenses and begins to view inner and outer reality more accurately.

Part-objects are now viewed as whole people, who have their own relationships and feelings; absence is experienced as a loss rather than a persecutory attack. Instead of anger, the baby feels grief. It is at around three months that a baby begins to cry real tears.

Oedipus Complex

At a conference in Salzberg in 1924, Klein dared to place the Oedipal complex at around one to two years – a much earlier stage than Freud’s six to seven years.

Where Freud’s development of the superego was seen as a good thing, Klein (1945) saw a hostile superego developing at the oral stage. She also delineated the experiences of girls and boys and gave more power to the mother.

In the Kleinian Oedipal stage, a world of part-object phantasies, boys want to protect their mother’s insides (her womb, or stomach) from their father’s aggressive penis. But, as in Freud, they fear their desire to castrate their father will be turned against them.

Girls driven by envy want to rob their mother of their father’s penis and unborn babies and are also paranoid about retaliation; but instead of castration, they fear instead a kind of hysterectomy. While the boy’s main anxiety object is the castrating father, the girl’s is the persecutory, almost magical mother.

The Oedipal crisis will morph the Depressive Position into one of separation

and loss.

Melanie Klein

Melanie Klein was born in Austria to a Jewish family, moved widely across Europe to escape the rise of fascism, and as a result was a member of the Budapest and Berlin Societies before escaping to England in 1927.

There she was championed by Ernest Jones of the British Psychoanalytical Society and The Bloomsbury Group, who translated her work as well as Freud’s.

Klein achieved extraordinary success as a psychoanalyst at the time despite being female in a male-dominated field, a single mother, and not having a medical degree.

Encouraged and trained by her mentors, Sandor Ferenczi in Budapest and Karl Abraham in Berlin, she was considered a theoretician as opposed to a clinician, basing her work on experience (clinical and personal) and an extraordinary gift for creative insight rather than scientific discovery.

Perhaps because she challenged him, Freud dismissed Klein, later defending his daughter Anna against her.

Critical Evaluation

Melanie Klein (1932) is one of the key figures in psychoanalysis. Her unabashed disagreements with Freudian theory and revolutionary way of thinking was especially important in the development of child analysis.

Her theories on the schizoid defenses of splitting and projective identification remain influential in psychoanalytical theory today.

For Kleinians, the aim of psychoanalysis is to enable the adult client to tolerate the Depressive Position more securely, even though it is never fixed and we all topple into paranoid phantasies and polarizing viewpoints. This echoes Freud’s aim to help patients achieve a state of ‘ordinary unhappiness’.

Psychoanalyst Jaqueline Rose (1993) has noted that, especially in the USA, Klein’s work has been rejected because of her violence and negativity. Klein herself wrote: ‘My method presupposes that I have been from the beginning willing to attract to myself the negative as well as the positive transference’.

Klein sits with the difficult emotions that her patients find hard to bear and helps them accept the complex, dark realities of relationships, the loss implicit in love, the annihilation implicit in life. When a therapist is able to tolerate these for a client, it dissipates their unbearable force.

Perhaps due to the shocking violence and negative bias of Klein’s infant phantasy world, the question that continues to be asked by Klein’s critics is this: Whose reality was Klein interpreting – her clients’ or her own?

How did Klein Disagree with Freud?

| Melanie Klein | Sigmund Freud |

|---|---|

| Places emphasis on interpersonal relationship | Places emphasis on biologically based drives |

| Emphasizes the intimacy and nurturing of the mother | Emphasizes the power and control of the father |

| Behavior is motivated by human contact and relationships | Behavior is motivated by sexual energy (the libido) |

| Klein stressed the importance of the first 4 or 6 months | Freud emphasized the first 4 or 6 years of life |

Take-home Messages

- Object relations theory is a variation of psychoanalytic theory.

- It places less emphasis on biologically based drives and more importance on interpersonal relationships (e.g., the intimacy and nurturing of the mother).

- In object-relations theory, objects are usually persons, parts of persons (such as the mother’s breast), or symbols of one of these. The primary object is the mother.

- The child’s relation to an object (e.g. the mother’s breast) serves as the prototype for future interpersonal relationships.

- Objects can be both external (a physical person or body part) and internal, comprising emotional images and representations of an external object (e.g. good breast vs. bad breast).

- The conceptualization of internal objects is linked to Klein’s theory of unconscious phantasy, and development from the paranoid-schizoid position to the depressive position.

References

Klein, M. (1921). Development of Conscience in the Child. Love, Guilt and Reparation, 252.

Klein, M. (1923). The development of a child. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 4, 419-474.

Klein, M. (1930). The importance of symbol-formation in the development of the ego. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 11, 24-39.

Klein, M. (1932). The Psychoanalysis of Children.(The International Psycho-analytical Library, No. 22.).

Klein, M. (1935). A contribution to the psychogenesis of manic-depressive states . International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 16, 145-174.

Klein, M. (1945). The Oedipus complex in the light of early anxieties. International Journal of Psycho-Analysis, 26, 11-33.

Klein, M. (1946). Notes on some schizoid mechanisms. Projective identification : The fate of a concept, 19-46.

Klein, M. (1961). Narrative of a child analysis: The conduct of the psychoanalysis of children as seen in the treatment of a ten year old boy (No. 55). Random House.

Rose, J. (1993). Why war?: Psychoanalysis, politics, and the return to Melanie Klein (p. 137). Oxford: Blackwell.