The Assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand

June 28, 1914

It is a historically accepted fact that the immediate flash-point that caused the First World War was the assassination of the Austrian Archduke Franz Ferdinand on June 28, 1914, in Sarajevo. This event set into motion a collision of the leading European states at the time and resulted in the catastrophe known as the Great War.

These sets of alliances and competing interests have been widely studied, and as such, the underlying nationalism and history of the Balkans tend to be ignored or explained away as a sort of backward Oriental primitivism. This interpretation could not be further from the truth, and the process that led to the tragic events of June 28, 1914, is worth examining in detail.

The Bosnian Connection

Although the roots of ethnic tensions and their modern incarnation in the form of nationalism go back several centuries in the Balkans, the genesis of the Bosnian situation in 1914 can be found in the 19th century. The land of Bosnia has long been the border between the Islamic Ottoman Empire and the Christian states of Austria and Hungary. This resulted in peculiar religious, demographic, and economic developments. It is generally accepted that pre-Ottoman conquest, Bosnia was inhabited by Christian Serbs and Croats. Ottoman rule brought Islamic law, religion, and custom, resulting in the establishment of a large class of native converts who in turn formed the backbone of the military and economic administration in the region. Society stratified along the lines of a ruling upper stratum of Muslims, and a lower class of Christians, holding the lower status of dhimmi, commonly known as a protected religious minority. The dhimmi formed the peasant/servant class and tended to work the lands of their Muslim overlords in a kind of feudal arrangement. Military pressure from the Christian states, coupled with Ottoman and local Muslim reluctance to embrace modernization meant that by the mid-1800s, Bosnia was significantly undeveloped as compared to its Christian neighbors.

Nationalism Emerges in the Balkans

Due to its particular social conditions, life in Bosnia remained stratified, and for the most part quite static. As the governing apparatus of the Ottoman empire weakened, its hold on the periphery slipped. Although uprisings and small-scale border warfare continued throughout the centuries, Bosnia remained in the firm, although slipping, hands of the Sultan. As such, the first stirrings of nationalism in the Balkans emerged in the Sanjak of Smederevo, to the East of Bosnia. The First Serbian Uprising was declared on February 14th, 1804. It was a direct response to the attempted elimination of the local Orthodox Christian notables by renegade Ottoman soldiers beyond the Sultan's control. The uprising was supported by Russia, an old rival of the Ottoman Empire. In addition, the rebels found sympathy and recruits across their borders, among the Serbian Orthodox populations of both the Austrian empire and Bosnia. The uprising was eventually crushed in 1813, but the spirit of independence could not be eliminated so easily. Punitive Ottoman taxation and forced labor resulted in another uprising in 1815, which would succeed where the first one failed. The result of the two Serbian uprisings was a semi-independent principality, that managed its own internal affairs, while notionally remaining loyal to the Ottoman Sultan. The catch with this was that the majority of Serbs remained outside the fledgling Serbian state, and thus the seeds for future conflict were laid down. Serbian agitators continued to push for the unification of what they saw as ancestral Serbian lands, while to the west the Croats inhabiting the region of Herzegovina looked to unite with their compatriots over the border in the Austrian Empire. Caught between these two forces was the Muslim population of Bosnia, who looked to the Sultan for protection. Unfortunately for them, the Sultan's hold over his dominions was slipping, with the Turkish Ottoman Empire widely being regarded as the sick man of Europe. Imperial Russia and the Austrian Empire looked at the crumbling Ottoman possessions as an avenue for future expansion, while national groups such as the Bulgarians, Serbs, and Greeks aspired to independence and nation-states of their own. The situation in the Balkans began to look more and more combustible as both outside powers and inside groups all vied for a piece of the Ottoman Empire.

The Great Eastern Crisis

By the year 1876, events in the Ottoman Empire came to a head. In a belated process of modernization, the Empire borrowed large sums of money from Western lenders, attempting to modernize its military and reform its society to remain more competitive with the growing Western powers. The Ottoman economy was over-reliant on agriculture, and when harvests failed in 1873 and 1874, the Empire's taxation policies proved inadequate. By October 1875, the Empire was forced to declare a default on its sovereign debt, and increased taxes throughout its Empire,

and in particular in the Balkans. The strain proved too much, and the Serbian inhabitants of Bosnia declared an uprising in 1875. Volunteers and arms began to pour in from Serbia and further abroad, while it wasn't long before the semi-independent states of Serbia and Montenegro declared war on their nominal Ottoman overseers in 1876. At first, the Ottoman Empire managed to contain and push back the uprising, as its newly professionalized army swept aside the opposition. However, it was long before the other powers sensed a chance and jumped into the fray. To the East of Serbia, the Bulgarian people rose up in opposition to Ottoman rule, hoping to take advantage of Ottoman preoccupation with the Western uprisings to establish their own nation-state. Their forces stretched, the Ottomans turned to irregulars, known as bashi-bazouks, to put down the Bulgarian uprising. These irregular forces were ill-disciplined, and committed atrocities on the civilian population. These atrocities gave Russia the casus-belli it was looking for, and on April 24, 1877, Imperial Russian forces poured over the Ottoman borders in both the Balkans and the Caucasus. The Russian army inflicted numerous defeats on the overstretched Ottomans and marched on the Ottoman capital of Constantinople. Russia imposed a punitive treaty on the Ottomans, wresting large chunks in the Caucasus from their control, and forcing the recognition of the Independence of a large Bulgarian state, as well as Serbia, Montenegro, and Romania. Fearing this vast expansion of Russian power in the Balkans, the other great powers of Europe organized a conference in Berlin to address the Great Eastern Crisis.

Recommended

The Congress of Berlin

The Congress of Berlin took place between June 13, 1878 and July 13, 1878. It was composed of representatives of the six Great Powers (Russia, Austria-Hungary, Italy, Germany, France, and Great Britain), as well as the Ottoman Empire and the four independent Balkan states of Serbia, Greece, Romania, and Montenegro. The conference was chaired by the German chancellor, Otto von Bismarck. He attempted to roll back certain Russian gains at the expense of the Ottoman Empire while maintaining a rough balance of power between the competing interests of

the remaining great powers, especially Austria-Hungary. The final results of the Congress left most of the actors dissatisfied, with the possible exception of Austria-Hungary, which got to occupy Bosnia and Herzegovina, as well as Novi Pazar to the south. The proposed new Bulgarian state was cut down in size, and given nominal autonomy, while Serbia and Montenegro obtained recognition of their independence and minor territorial concessions. This situation created future tensions, as large numbers of Serbs, Bulgars and Greeks remained in lands still controlled by the Ottoman Empire, while the Ottomans were humbled in defeat and lost large chunks of territory. Bosnia would remain the biggest point of contention, as Austria-Hungary received a new colony even though it took no part in the war, while Serbia felt especially aggrieved as its main objective during the war was to link up with the Serbian rebels of 1875 and integrate Bosnia into its domains. Thus, far from solving the Balkan question, the Congress of Berlin laid the seeds for the events that would directly lead to the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand.

The Balkan League

However much it objected to the Austrian occupation of Bosnia, Serbia was a minnow compared to it and had to accept the decision of the Congress. As well, Russia felt disappointed with the results, and over the next few decades, a growing rivalry developed on the one hand between Austria-Hungary and its ambitions for the Balkans, and Russia, which also had designs on the territory. While Austria aimed for gradual occupation, Russia worked through the small independent states in the Balkans, that had designs both on Ottoman as well as Austrian territory. In 1908 the Ottoman Empire underwent a revolution, and taking advantage of the turmoil, Austria-Hungary formally annexed Bosnia and Herzegovina, angering both the Serbs and Russians. Feeling humiliated, the Russians pursued the creation of a Balkan League, which they hoped to turn against the Austrians. The league, however, had different goals in mind, and the four nations of Serbia, Bulgaria, Greece, and Montenegro turned on the Ottomans, aiming to capture the European territories of the Empire and free their compatriots. In short order, the League overwhelmed the Ottomans, who were drained by a war with Italy over Libya the preceding year. Although the League splintered shortly after defeating the Ottomans, with Bulgaria attacking its former allies and being stripped of much of its gains, the end result was the virtual elimination of the Ottoman Empire from Europe. Serbia doubled in size and population, and having freed the Serbs living under Ottoman rule, turned its sights on the Serbs and other South Slavs living under Austrian rule. The Serbs were split between the ideas of a Greater Serbia or a Yugoslavia (land of the South Slavs), and both state and non-state actors vied with one another to accomplish the goals of national unification.

The Black Hand

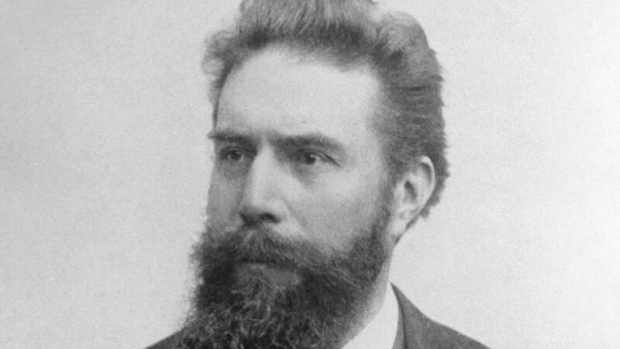

Although the main drivers of nationalism and expansion at the expense of the Ottoman Empire were the national governments in the Balkans, shadowy unofficial groups played a part, often with the tacit support of said states. The most prominent example of this was the Black Hand, a group of nationalist Serbian army officers that wished to create a Greater Serbia out of the Serb-inhabited lands in the Balkans. The Black Hand was formed on 9 May 1911, but its origins lie further back. The officers that formed the Black Hand were involved in the 1903 assassination of the Serbian royal couple, who were from the Obrenovic dynasty, which brought the Karadjordjevic dynasty to power. As such, the Black Hand was feared and held significant behind-the-scenes power. It is however debatable whether the government actively encouraged the Black Hand, or tolerated it, and whether this tolerance was out of fear, or out of sympathy with the irredentism goals of the Black Hand. The Balkan Wars were a significant boost to the society's numbers, such that by 1914 the society had hundreds of members, mostly officers serving in the Royal Army. The group promoted the training and organization of guerrilla bands and engaged in terrorist activity to further the Serbian national cause. Once the southern lands had been conquered, the leaders of the Black Hand focused their efforts on the Austro-Hungarian empire, organizing assassinations and terror attacks against the Austro-Hungarian officials. They were also especially worried by the rumors that the heir-presumptive to the Austro-Hungarian throne, Archduke Franz Ferdinand, had plans to create a triune kingdom, with a Slavic component to it. This was an attempt to head off discontent and rising nationalism among the South Slavic population, but doubts exist as to the historical accuracy or seriousness of the Archduke's plan. The decision was taken to strike when the Archduke visited Bosnia in the summer of 1914, a plan for which Bosnian operatives (5 Serbs and 1 Muslim Bosniak) had been preparing for months.

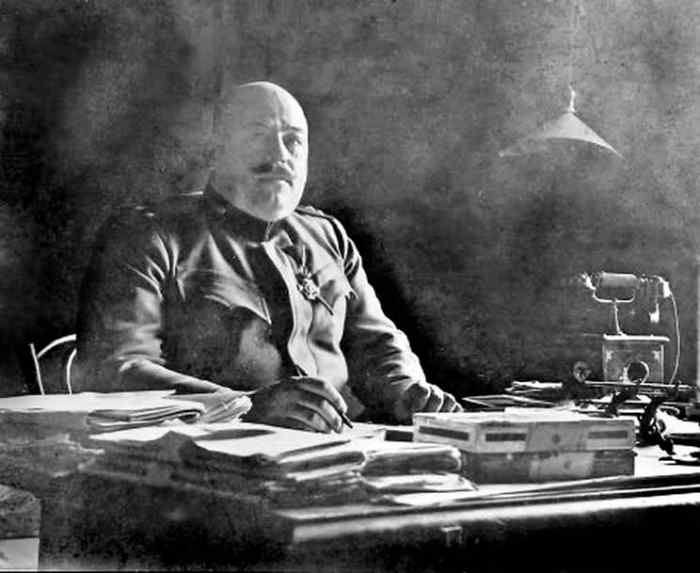

The Assasination of the Archduke and His Wife

The Archduke and his wife were due in Bosnia to observe military maneuvers, after which they would tour Sarajevo to open the new branch of the state museum. The Archduke and his wife were travelling in an open-top carriage, with a driver who was unfamiliar with the route and had minimal safety precautions. They were met by Governor Oskar Potiorek at the Sarajevo train station, who had prepared a six automobile convoy. There was a mix-up at the station, and the special security detail was left behind. The Archduke and his wife Sophie were riding in the back of the third car, with the top down. Not to be outdone in farce, the assassins were not much better with their planning. Although six assassins were trained and in position that fateful day, it was the final, Gavrilo Princip who fired the fatal shots. The first two assassins failed to act as the convoy drove in front of them, either through incompetence or fear. The third assassin was armed with a bomb, which he managed to throw at the car carrying the Archduke and his wife. The bomb bounced off their car, and as it was on a timer, it detonated under the next car in the convoy. The assassin, Nedeljko Cabrinovic, attempted to commit suicide by swallowing a cyanide pill, but the dose was too small. He was severely beaten by the crowd before he was taken into custody. His actions led to anywhere between 16 and 20 wounded civilians. The procession sped up and blew by the next two assassins, who failed to act due to the speed of the convoy. The convoy reached the town hall, whereupon the route was changed as the royals wished to go visit the wounded civilians in the hospital. To compound the earlier mistakes, the driver of the royal car was not informed of the changed route and made the fatal wrong turn back down the original path. Governor Potoriek yelled at the driver to stop and reverse his car, at which moment the final assassin, Gavrilo Princip leapt out and shot the Archduke and his wife. With this action, Gavrilo Princip set into motion a series of events that would forever change not only Europe, but the rest of the world.

Long-Lasting Consequences

It would be an over-simplification to lay the blame solely on Gavrilo Princip's shoulders, as his foolish actions were only the culmination of a series of miscalculated political and diplomatic moves. As we have seen, imperial ambitions in the Balkans clashed with nationalist aspirations to produce a volatile situation. Emerging national groups were challenging the domination of old Empires, at precisely the same time that these Empires faced pressing internal problems. Economic and political change added more volatility to the mix. The assassination of the Archduke and his wife was used as a convenient pretext by the Austro-Hungarian empire to crush Serbia once and for all and solve the problem of nationalist agitation in its south borderlands. The cascading set of alliances drew in more and more nations, as first Serbia was backed by Russia, and Germany backed the Austro-Hungarians. The French had an alliance with Russia, and when the Germans invaded Belgium in an attempt to roll the French flank, the United Kingdom joined the fray. Ottoman Turkey and Bulgaria were enticed to join the war by promises of Serbian land, and within a year, the world was engulfed in chaos. By the time the dust settled, all three Empires involved in the region (Imperial Russia, the Ottoman Empire, and Austria-Hungary) would cease to exist, victim to the folly of their own ambitions and the rising ethnic nationalism that swept the region. The minor states involved would suffer immensely as well, with Serbia losing roughly 25% of its pre-war population. The final denouement of this saga played out in the 1990s, as a brutal civil war ripped apart the unitary Yugoslavian state formed by Serbia and the South Slavic inhabited lands of the former Austro-Hungarian empire. At the center of this war was Bosnia and Herzegovina, still haunted by the ghosts of previous centuries.