Karina Longworth Makes Old Hollywood New

The writer and critic has found a cult following with her podcast, You Must Remember This, unpacking the myths to show age-old stories and stars in a new light.

These days, the closest thing Los Angeles gets to Old Hollywood magic comes from a converted closet in a guest house in Los Feliz. There, in a space swaddled with thick black padding, using just a microphone and an iMac balanced precariously atop a pile of wooden crates, Karina Longworth conjures cinematic ghosts back into existence.

The ritual always begins the same way. Longworth once compared the ambience of You Must Remember This to a séance, and there’s something eerie about the way the podcast begins, with the quiet scratch of an old record, the fragments of murmurs layered together, and a distorted Dooley Wilson singing “As Time Goes By.” When Longworth’s voice comes in, it’s clipped and almost comically precise, welcoming listeners into her aural investigation of classic film and its most indelible characters. Her catchphrase is less an invitation than an imperative: “Join us, won’t you?”

If you’re one of the hundreds of thousands of people who listen to You Must Remember This (Longworth is cagey about specifics, but says that each episode’s downloads reach six figures), you’re aware of the distinct project that Longworth has formed her career around. She described it to me as “writing and research about old movies,” which doesn’t exactly do it justice. Longworth is Old Hollywood’s most vital historian. Four years in, You Must Remember This has spawned more than 140 episodes over multiple seasons, delving into Hollywood lore in all its sticky, self-replicating, unreliable complexity. “Dead Blondes,” released in 2017, mined the careers of Marilyn Monroe, Jayne Mansfield, and Grace Kelly, while reintroducing lesser-known actors such as Barbara Loden and Dorothy Stratten. Longworth’s 2015 series on Charles Manson’s murders was so intricately researched that it was frequently cited as a definitive source on Manson after his death last year.

Since Longworth started podcasting in 2014, out of a simple desire to produce something that might get her a programming job at a film festival or Turner Classic Movies, You Must Remember This has found a cult following. Part old-timey radio show, part reportorial deep dive, it picks lovingly at the stars in the Old Hollywood firmament. Longworth has brought a new perspective to some of the most overexposed stories and characters in film history, producing chronicles that incorporate her narration and research with fragments of actors reproducing real dialogue. But she’s also introduced a new generation of cinephiles to less-enduring actors like Linda Darnell and Olive Thomas, giving credence to women whose talent and biographies were buried. With an academic’s approach to research and a critic’s eye for quality, Longworth interrogates Old Hollywood: its myths, its icons, its injustices.

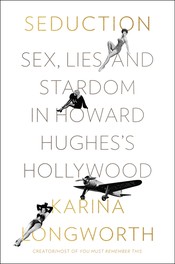

In that sense, she’s become the interpreter that classic cinema deserves. “Karina’s mapping out the history that will shape how we understand Hollywood not just today, but 20 years from now,” the film critic Amy Nicholson told me. You Must Remember This has delved into the Metro-Goldwyn-Mayer studio system and its influence on the film industry. It’s explored the anti-communist blacklist of the ’40s and ’50s, and the highly sensationalized trial of Roscoe “Fatty” Arbuckle for the manslaughter of Virginia Rappe, among other chapters in history. Longworth has considered the lives and careers of people from Humphrey Bogart to Jane Fonda to Rudolph Valentino. In her new book, Seduction: Sex, Lies, and Stardom in Howard Hughes’s Hollywood, she uses the legendary producer and aviator as a frame (a “Trojan horse,” in her description) to tell stories about what she’s really interested in: the many women in Hughes’s orbit.

The project is characteristic Longworth, in that it takes a subject who’s been relentlessly scrutinized and uses him as a springboard into richer terrain. It’s essentially, she says, an empathetic series of stories about actors in the first half of the 20th century, disguised as a book about Howard Hughes’s sex life. Hughes himself is present, documented from his precocious beginnings to his isolated, codeine-addicted end. But he’s not the point. The stories Longworth uncovers—about Katharine Hepburn and Jane Russell, yes, but also Ida Lupino and Faith Domergue and Anita Loos—are so rich, so compelling, that they urge you to question how much else in history has been lost within the swirling vortex of Great Men.

They also present a compromise, at least when it comes to thinking about Hollywood and the badly behaved men who’ve made most of its masterpieces. Longworth is a detective, investing exhaustive efforts into separating fact from fiction—when possible—and exposing the truth about how women in the classical Hollywood era were treated. (Some of the more remarkable documents cited in Seduction include a studio press release issued about Lupino’s weight and a memo Howard Hughes once drafted about Jane Russell’s breasts.) But she’s also a genuine fan. “More than anything,” the director Rian Johnson—Longworth’s fiancé—says, “she loves finding the unexplored corners of film history, or the unseen angles of stories we all thought we knew … When she’s found something like that, she lights up.”

And learning more about those behind-the-scenes stories doesn’t contaminate how she feels about the films themselves. For her, it makes them seem more valuable, more fascinating as cultural artifacts. If anything, she says, “the more I do this, the more I feel passionate about doing it. Because there’s so much more to say, and there’s so much more to correct.”

You Must Remember This is a production, but it’s one specifically tailored to its presenter’s requirements. Longworth mostly writes the scripts, those paeans to cinematic glitz, in a rented office in what she describes as “a bad neighborhood along a freeway.” If she sounds like she’s delivering her monologues while sporting a Veronica Lake side-sweep and crimson lipstick, in reality she’s wearing “the softest cotton clothes ever” so she doesn’t feel uncomfortable while working. She records the podcast in the closet at the back of the home she shares with Johnson, and she’s resisted building a more permanent studio because “I don’t know how long I’ll be doing the podcast, you know? It’s not like podcasting itself is my life’s work.”

And yet there’s an indisputable kind of magic to the way she does it. Each episode is loaded with research and facts, stuffed with everything Longworth has gleaned from her intensive reading and archive dives, but somehow reanimated into storytelling. The actor Noah Segan, who voices many of the real-life characters in You Must Remember This, describes Longworth as a gifted director who has an uncanny sense of the components required to bring her writing to life. “She directs like a journalist,” Segan says. “She’s looking for very specific information in the read, she’s looking for something that feels authentic, and she’s also aware that performing the lines and the characters does have an X factor.”

When Longworth first created the podcast, it was the natural manifestation of what felt like her lifelong fascination with classic film and its characters. She grew up in Studio City, Los Angeles, where film stars were mentioned on the local news and everybody was interested in movies. Her mother had a passion for films from the ’50s and ’60s that she shared with her daughter. If Old Hollywood feels like a niche interest now, Longworth says, it didn’t always: When she was growing up during the 1990s, “it was as important if you wanted to be part of the cultural conversation to have seen Citizen Kane as it was to have listened to the Velvet Underground.”

After studying art at the Art Institute of Chicago and the San Francisco Art Institute, Longworth moved to New York to pursue a master’s degree in cinema studies. Her initial plan was to enter academia, but she didn’t enjoy writing in an academic voice and found the performative aspect of teaching to be uncomfortable. “It’s very difficult for me to teach,” she says. “I’ve tried it at different points in my life and it’s just not for me.” She was working at a pasta factory in New York when she started writing for a blog about independent film that became Cinematical. After the journalist who was hired to edit it left the project, Longworth was hired as editor in chief before she’d even finished her graduate degree, running a film site that had previously paid her five dollars per post as a writer.

Longworth’s résumé is a fascinating illustration of how much media has changed over the past 20 years. Longworth was a blogger before blogging was mainstream, an experience she parlayed into her dream job of film critic at LA Weekly. As alt weeklies across the U.S. began shrinking and cutting talent at the top of the masthead, Longworth lost most of her mentors, along with her enthusiasm for contemporary criticism. “I’m not somebody who’s excited to generate opinions,” she says. “In any given year, there are probably 20 to 30 movies that I’m excited about, and there are 12 to 15 movies that come out each week.”

In 2014, after she had been writing and editing for almost a decade, and a little more than a year after she left LA Weekly, Longworth started working on You Must Remember This. Podcasting wasn’t quite the dominant force it would soon become (Serial, for context, debuted later that same year), and Longworth didn’t have a plan beyond making something that could be a showcase for her particular skills. Her first episode was an examination of the interrupted trajectory of Kim Novak, the actor who played what Longworth described as “the ultimate Hitchcockian icy blond fetish object” in Vertigo, and whose appearance at the 2014 Academy Awards had sparked the same kind of obsessive dissection of her physicality that defined Novak’s acting career in Hollywood.

The swiftness with which You Must Remember This gathered attention and acclaim took Longworth by surprise. The A.V. Club’s Podmass blog quickly praised her “compelling stories” and thoughtful examination of the “often corrosive effect Hollywood has [on] those who choose to live in it.” Entertainment Weekly followed suit. You Must Remember This was recruited to join American Public Media’s podcast network, and it quickly grew a substantial audience. What Longworth describes as a “personal art project” was suddenly a hit. “The only thing that I can say is that it’s very genuine,” she says. “It’s not trying to be anything other than what it is. And for the first time, of anything I’ve done in my career, I’m not trying to appeal to any specific format or any specific audience, and I think people respond to that.”

What makes You Must Remember This so distinctive is its marriage of so many different elements. Longworth’s friend, the culture critic Rachel Syme, says that she is “the most amazing researcher … but then her synthesis is so beautiful, taking all these disparate facts and weaving them into a story.” In a place and an era where myth is more deeply engrained in the historical fabric than truth can ever be, Longworth is rigorous about checking facts but transparent about what can’t be known.

She’s also constantly informed by an awareness that film history has always lionized men as brilliant, complex entities while reducing women to component, easily replaceable parts. “The thing about Old Hollywood stars is that they calcify so easily. They become these images, like Marilyn, forever stuck in time in the white dress,” Syme says. “Karina is really good at helping you contextualize what people’s lives were like, women’s lives especially. She reanimates people from black-and-white and puts them into color.”

Then there’s the voice. Longworth downplays any question of a podcasting persona—she’s just acting, she says, to the limits of acting that she’s capable of, and the voice is simply a controlled way of speaking that seems to happen when she’s standing up to record. But in a medium where “podcast voice” has become its own phenomenon, she does something different, specifically enunciating certain letters and imbuing her text with a plosive, expressive emphasis. Her delivery has won its own legion of fans (“My friends and I were talking once about how we have an ASMR response to her voice,” Syme says), while contributing to the dramatic nostalgia of You Must Remember This. Longworth’s delivery transports listeners to the 1930s, even if her critical analysis and deconstruction of Hollywood couldn’t come from any moment but the present.

In one chapter of Seduction, Longworth describes Howard Hughes and Katharine Hepburn taking pleasure in the eternal Hollywood “tug-of-war with the press.” Both craved notoriety and attention, but without their accompanying cost. And both “wanted to be the most talked-about and celebrated person in their respective fields,” Longworth writes, “without ever having to reveal themselves to anyone outside of their immediate circle.”

The concept of fame, and what actual value it represents, comes up again and again in Longworth’s work. At one point in the actor Billie Dove’s career, Longworth writes in Seduction, Dove was receiving 37,000 fan letters a month, a number that was “as valuable a measure of popularity then as an actress’s number of Instagram followers would be now.” Fame is presented in the book as its own distinct entity—separate from talent and success, if not wholly separable. It also tends to have a more pronounced and lasting impact than either.

If Howard Hughes is best known now as an aviator and a producer, his real genius, Longworth told me, wasn’t related to either—it was in his ability to manipulate Hollywood’s publicity machine in ways that still resonate a century later. Even as a very young man, his instincts told him that he could succeed by manufacturing his version of the truth and repeating it enough until others did, too. “Hughes may have been irresponsible, reckless, tacky, and dangerously ignorant,” Longworth writes in Seduction, “but he was also entertaining.” And he understood the value that could be gleaned from that ability to draw people in, even if he also repelled them.

Longworth’s career thus far has been defined by looking at Old Hollywood through a modern lens, examining heroes and legends from a contemporary perspective. But her mission also seems to be to pinpoint and correct fame’s distortions. For every Hughes and Hepburn, skilled manipulators of the media who used fame to their benefit, there are forgotten actors like Linda Darnell, whose husband once tried to sell her to Hughes, and whose own biographer diminished her talent.

The irony is that Longworth’s success has increasingly meant that the podcast host and author has had to navigate fame for herself, trying to balance privacy with acclaim and success in a public-facing profession. At this point in her career, she’s often recognized. In the most recent season of the Netflix drama Dear White People, two characters rhapsodized about You Must Remember This and even mimicked Longworth’s presentation. But Longworth seems to resist hype. She doesn’t have a publicist; she tries to minimize the events she participates in, like film screenings and panel discussions.

A decade ago, when she was a film critic for LA Weekly, she wore distinctive cat-eye glasses and sported a more retro aesthetic (an interviewer for The Guardian once described her as being “like something straight out of a 1950s edition of the Hollywood Reporter”). But Longworth seems frustrated now that people often expect her, in person, to be “cosplaying the 1940s.” She’s had Lasik eye surgery and the glasses are long gone. She still carries herself with a discreet, slightly fierce kind of glamour—her Instagram page bears a handful of photos in which she radiates both intensity and reticence.

Even those photos seem to be a kind of negotiation: Longworth told me in one interview that she’d quit Instagram because she disliked feeling pressured to present herself for public consumption, and she didn’t think what she looked like should have anything to do with what she did for a living. “When I was 25 I wanted to be famous, and now that I’m 38, I don’t,” she says. “I want to have just enough notoriety to be able to keep working. I don’t want people to take pictures of me, I don’t want to be on TV. I just want to be able to work.” (A few days later, she posted two more pictures to her page, seemingly out of an obligation to promote her book.)

There’s some irony in the fact that Longworth’s career is now embodying the same kinds of tensions that she’s spent more than a decade exploring. Finding success in the entertainment industry, even as a writer, increasingly requires selling an image, even if your specific comfort zone involves mostly working inside a soundproof closet, alone. Longworth is adamant, too, that there’s a gendered element to what people expect from her: Because she’s a woman, she’s supposed to be the face of her work and her product in a way that men might find it easier to avoid.

The thing about Hughes that Longworth most empathizes with, she says, is his desire to be recognized for his achievements while not wanting people to know too much about who he actually was. Her long-term goal is to ultimately move into film and television, using archival film to tell visual stories about Hollywood history. She cites the British documentarian Adam Curtis as an example. For one thing, he has what seems like open access to the BBC’s archives. For another, she says, “I don’t think anybody knows what that guy looks like.”

What seems certain is that she’ll continue her work of trawling through Hollywood history, correcting instances where myth outlives the truth, and elevating the actors, writers, and directors who merited more glory than they received during their lifetime. It’s work that adds texture to the historical record of classic film without dampening its perpetual luster. Darnell is an example of somebody “who had an incredibly tragic story, somebody who was really destroyed by fame,” Longworth says. “And [knowing this] doesn’t make her movies less interesting or repellent to me at all. It makes them more fascinating, and it makes it easier for me to empathize with her as a human being trying to do a job. It makes me want to champion her.”