This Woman Saved the Americas From the Nazis

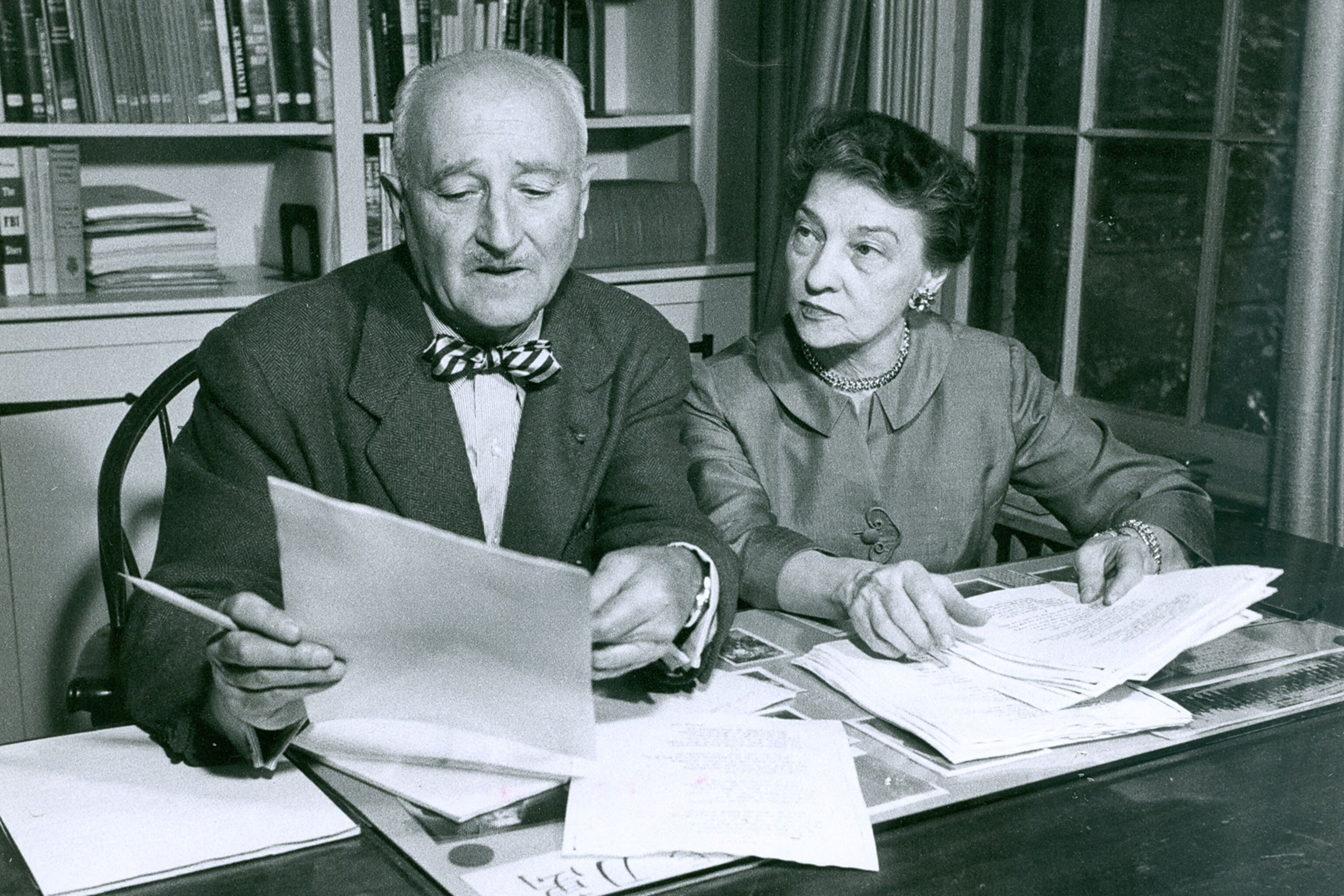

Pioneering codebreaker Elizebeth Friedman, a poet and mother of two, smashed spy rings by solving secret messages.

British codebreaker Alan Turing had a movie, The Imitation Game, made out of his life—and Benedict Cumberbatch to play him. The great American codebreaker Elizebeth Friedman hasn’t been so lucky. Although she put gangsters behind bars and smashed Nazi spy rings in South America, Friedman’s name has been forgotten. Her work remained classified for decades, and others took credit for her achievements. (Find out what secret weapon Britain used against the Nazis.)

Jason Fagone rescues this extraordinary woman’s life and work from oblivion in his new book, The Woman Who Smashed Codes. When National Geographic caught up with Fagone by phone, he explained how Friedman, like Alan Turing, broke the Enigma codes to expose a notorious Nazi spy, how J. Edgar Hoover rewrote history to sideline her achievements, and how the cryptology methods that she and her husband, William Friedman, developed became the foundation for the work of the National Security Agency (NSA). (Go inside the daring mission that stopped a Nazi atomic bomb.)

Elizebeth Friedman is probably not a name familiar to most of our readers. Introduce us to this remarkable woman—and explain what drew you to her.

Well, it’s an amazing American story. A hundred years ago, a young woman in her early twenties became one of the greatest codebreakers America had ever seen. She taught herself how to solve secret messages without knowing the key. That’s codebreaking. And she started from absolutely nothing.

She wasn't a mathematician. She was a poet. But she turned out to be a genius at solving these very difficult puzzles, and her solutions changed the 20th century. She caught gangsters and organized-crime kingpins during Prohibition. She hunted Nazi spies during World War II.

She also helped to invent the modern science of secret writing—cryptology—that lies at the base of everything from government institutions like the NSA to the fluctuations of our daily online lives. Not bad for a Quaker girl from a small Indiana town! [Laughs]

We first meet Elizebeth at a mansion named Riverbank near Chicago that belonged to a notorious millionaire named George Fabyan. Paint a picture of this larger-than-life man—and explain his obsession with Shakespeare.

Fabyan was a lot like William Randolph Hearst or Andrew Carnegie—one of these incredibly wealthy Gilded Age multimillionaires who’d made his fortune in the textiles industry. Unlike a lot of other Gilded Age rich men, Fabyan didn’t go for lavish vacations on the French Riviera or collect art. He dreamed of discovering the secrets of nature. Although he was a high school drop-out, he saw himself as a great sponsor of science, somebody who used his fortune to bring together some of America’s finest scientists and give them carte blanche to discover the secrets of the world.

He was very eccentric. He lived in a villa full of furniture that hung from the ceiling on chains. His couch and bed hung on chains. He was extremely suspicious of everyone around him. He kept a hive of honeybees inside his own personal house because he didn’t trust them to make honey unless he surveilled them personally. [Laughs]

One of his obsessions was secret writing. He believed that Shakespeare wasn’t the author of the famous plays, like Hamlet and Julius Caesar. He thought that they were written by one of Shakespeare’s contemporaries, the philosopher Francis Bacon.

Fabyan believed Bacon had placed secret messages inside the original 1623 edition of the plays as a signature of his authorship and was convinced these secret messages could be discovered, thereby rewriting the history of English literature. To do that he hired some of the world’s most prominent Bacon and Shakespeare experts and brought them to Riverbank. That’s how Elizebeth Friedman, then Elizebeth Smith, ended up at Riverbank at the age of 23 as a codebreaker.

Elizebeth cut her teeth as a codebreaker during Prohibition in the unlikely role of interdicting rumrunners. Set the scene for us—and describe how she reacted to becoming a minor celebrity.

After she left Riverbank in 1921, she moved to Washington and was soon recruited by the U.S. Treasury Department to fight illegal liquor smuggling that had grown because of Prohibition. Rumrunners used ships that could outrun the Coast Guard vessels to smuggle rum into the U.S. The Coast Guard was unable to stop them because the rumrunners got good at concealing their operations using coded radio messages. Thousands of these messages were piling up in the Coast Guard offices so they approached Elizebeth Friedman to get help reading them.

Between 1926-1930, she solved 20,000 smuggling messages per year in hundreds of different code systems. She did it all by hand with pencil and paper, before the era of computers. It was analog heroism.

Toward the end of the 1920s, she also began to testify in court against some of the biggest gangsters of the day. These criminal cases required her to explain to juries how she had solved these secret messages. She would go into court carrying her handbag, wearing a pink dress and hat with flower pins, and would explain to a jury exactly how she had intercepted these radio messages and decoded them.

Some of these guys were very dangerous. She testified in one case in New Orleans against three lieutenants of Al Capone.

As a result, she became one of the most famous codebreakers in the world. She was known as the Lady Manhunter, or the Key Woman of the Keyman, “keyman” being a nickname for a treasury agent, similar to G-Man in the FBI. She was on front pages from coast to coast and she hated all of it! [Laughs] She was a very modest person, and disdained what she later called the hero worship.

The publicity also created problems because codebreaking is normally a secret profession. You are revealing the secrets of people who are communicating secretly and the more you reveal about how you found those secrets, the easier you make it for people to conceal their future communications.

Today, most codebreaking is done by computers. What sort of methods did Elizebeth have at her disposal?

Great question! She did everything with pencil and paper and a series of techniques, some of which had been around for hundreds of years and some she had to invent herself. Working with William Friedman, who later became her husband, in the early days of Riverbank, she created different approaches and attacks on secret messages that allowed her to pick apart garbled blocks of letters and arrange them into patterns that made sense.

Over decades of practice, solving tens of thousands of messages every year, she developed an intuition, a way of thinking that made her one of the best in the world at seeing the shapes of words in a field of letters that nobody else could make sense of.

Her achievements reached their peak in World War II in what came to be known as the “invisible war.” Take us inside this murky world of espionage and counterintelligence.

After Hitler invaded Poland in 1939, and World War II began, the codebreaking team Elizabeth had built within the Coast Guard started to intercept and analyze messages that looked a lot like rumrunning messages but were actually being sent by Nazi spies. These spies were spreading into South America, which was a neutral continent then, and into the U.S. and Mexico. All of a sudden, Elizebeth’s team, which had been focused on smuggling, became a team that hunted Nazi spies.

In the process, she met figures from British intelligence. The British sent over a lot of young officers, who looked to all the world like they were just British chaps having a good time, but were actually spies. One was Ian Fleming, who would go on to write the James Bond novels. Another was a young Roald Dahl, who at that time was a handsome pilot in the RAF.

She also worked on the notorious Enigma codes. While Alan Turing was organizing large-scale attacks on enigma codes using algorithms and large electromechanical devices called bombes, Elizebeth was more narrowly focused on a couple of Enigma’s systems being used by Nazi spies. That’s how the notorious SS spy Johannes Siegfried Becker, nicknamed “Sargo,” was encrypting reports he sent back from South America to Berlin.

The FBI considered Becker the most dangerous Nazi spy in the Western Hemisphere. He directed more than 50 agents from a base in Argentina, exchanging thousands of sensitive espionage reports with Germany, gathering information on U.S. and British military capabilities and instigating military coups in South American countries to swing governments toward the Nazis. Elizebeth’s efforts led to the destruction of every Nazi spy network in South America, in particular the one run by “Sargo.”

You write that, “by any measure, Elizebeth was a great heroine of the Second World War.” But her role was erased by J. Edgar Hoover. Explain what happened.

The FBI had responsibility for catching Nazi spies in South America and those were the networks that Elizebeth was tracking. So she was giving messages to the FBI and also providing them with materials so they could solve messages themselves. Without Elizebeth and her team, the FBI would have been completely lost.

But after the networks were destroyed toward the end of 1944, J. Edgar Hoover launched a publicity campaign to take credit for winning this invisible war, claiming that the FBI was solely responsible. He produced a film that was shown to U.S. troops called “The Battle of the United States,” which portrayed the FBI as the main hero, and published articles in popular magazines about the FBI’s great work. He did not credit Elizebeth or her team.

To this day historians wrongly praise Hoover and the FBI for achievements that were actually Elizebeth’s. As a result, Americans have no idea that Elizebeth Friedman, a mother of two, was the great Nazi spy catcher of the war.

The National Security Agency hit the headlines with whistle-blower Edward Snowden. Describe the Friedmans' role in its creation in 1952.

Elizabeth and William are the Adam and Eve of the NSA in the sense that they were present at the birth of U.S. codebreaking at Riverbank in 1916. Everything that happened afterward grew out of that time and place. Elizebeth also helped to invent the science that undergirds a lot of the NSA’s work. But she had no direct role in the NSA’s creation. It was her husband, William Friedman, who helped create it.

The Army codebreaking unit that William launched in the early 1930s, and led all through the war, decrypted Japanese cypher machines, leading to major U.S. victories. After the war that unit became absorbed into the agency that we now know as the NSA.

William was an NSA official for a number of years, until he began to believe that the NSA was collecting too much information and keeping too much of it classified. He became suspicious about the direction of an institution that, in many ways, he helped create, and eventually came to believe that the NSA’s practices were a threat to democracy itself. In private letters, he made criticisms of the NSA that are reminiscent of Edward Snowden’s criticisms decades later.

You write, “The world forgot about her and remembered him.” Why do you think this was?

Sexism? [Laughs] Part of the reason she was forgotten after the war is because of secrecy. Her records were classified, stamped “Top Secret Ultra,” and carried off to what she called “government tombs.” Thousands of pages of her decryptions and proof of everything she had done in the war were placed under lock and key in the National Archives until as late as the year 2000.

Along with many other American women who wrote codes during the war, she was told that if she ever spoke about it, even to her grandchildren, she would be prosecuted. So she didn’t. As a result, for many years nobody knew what she had done in the war.

This interview was edited for length and clarity.

Simon Worrall curates Book Talk. Follow him on Twitter or at simonworrallauthor.com.

Related Topics

You May Also Like

Go Further

Animals

- We finally know how cockroaches conquered the worldWe finally know how cockroaches conquered the world

- Move over, honeybees—America's 4,000 native bees need a day in the sunMove over, honeybees—America's 4,000 native bees need a day in the sun

- Surveillance Safari: Crowdsourcing an anti-poaching movement in South Africa

- Paid Content

Surveillance Safari: Crowdsourcing an anti-poaching movement in South Africa - Fireflies are nature’s light show at this West Virginia state parkFireflies are nature’s light show at this West Virginia state park

- These are the weird reasons octopuses change shape and colorThese are the weird reasons octopuses change shape and color

Environment

- Connecting a new generation with South Africa’s iconic species

- Paid Content

Connecting a new generation with South Africa’s iconic species - These images will help you see coral reefs in a whole new wayThese images will help you see coral reefs in a whole new way

- What rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlifeWhat rising temperatures in the Gulf of Maine mean for wildlife

- He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?He’s called ‘omacha,’ a dolphin that transforms into a man. Why?

- The northernmost flower living at the top of the worldThe northernmost flower living at the top of the world

History & Culture

- These modern soldiers put Bronze Age armor to the test–how did it hold up?These modern soldiers put Bronze Age armor to the test–how did it hold up?

- Should couples normalize sleeping in separate beds?Should couples normalize sleeping in separate beds?

- They were rock stars of paleontology—and their feud was legendaryThey were rock stars of paleontology—and their feud was legendary

- Scientists find evidence of ancient waterway beside Egypt’s pyramidsScientists find evidence of ancient waterway beside Egypt’s pyramids

Science

- Can a spoonful of honey keep seasonal allergies at bay?Can a spoonful of honey keep seasonal allergies at bay?

- Scientists just dug up a new dinosaur—with tinier arms than a T.RexScientists just dug up a new dinosaur—with tinier arms than a T.Rex

- Why pickleball is so good for your body and your mindWhy pickleball is so good for your body and your mind

- Extreme heat can be deadly – here’s how to know if you’re at riskExtreme heat can be deadly – here’s how to know if you’re at risk

Travel

- For a wellness break, head to the Dolomites' Alpe di SiusiFor a wellness break, head to the Dolomites' Alpe di Siusi

- The ‘Yosemite of South America’ is an adventure playgroundThe ‘Yosemite of South America’ is an adventure playground

- These farmers make it possible for hikers to access Alpine trailsThese farmers make it possible for hikers to access Alpine trails