Why Friendship Is Like Improv

“If I’m onstage with people I’ve been performing with for 20-some years … I never get left hanging.”

Every week, The Friendship Files features a conversation between The Atlantic’s Julie Beck and two or more friends, exploring the history and significance of their relationship.

This week, she talks with three of the co-founders of the Upright Citizens Brigade sketch-comedy and improv troupe. Matt Besser, Matt Walsh, and Ian Roberts—along with Amy Poehler—took the group from the Chicago improv scene to New York, onto television with a sketch show in the ’90s, and turned it into the big business it is today. UCB now has theaters in New York City and Los Angeles, and also offers improv classes, whose alumni include many other famous comedians, such as Aubrey Plaza and Donald Glover. In this interview, Besser, Walsh, and Roberts discuss UCB’s origins, how the improv social scene has changed over time, and how the nature of improvisation makes friendship among performers necessary and inevitable.

The Friends:

Matt Besser, 51, an actor and a co-founder of the Upright Citizens Brigade who lives in Los Angeles. He hosts the comedy podcast Improv4humans With Matt Besser.

Ian Roberts, 53, an actor, a writer, and a co-founder of UCB who lives in Los Angeles. He served as the showrunner for the Comedy Central show Key and Peele and the TV Land show Teachers.

Matt Walsh, 54, an actor and a co-founder of UCB who lives in Los Angeles. He recently starred in the HBO show Veep.

This interview has been edited and condensed for clarity.

Julie Beck: Let’s go back to the very beginning: When and how did you guys first meet?

Matt Besser: In Chicago. Even before I knew about improv, I was going to this place called the Roxy, which was a stand-up open mic where people would do sketches and stuff. Walsh, would you agree? Is that where we met? At the Roxy?

Matt Walsh: Yeah that’s about right. I remember meeting Ian on my back porch—

Ian Roberts: I need to jump in here about your first meeting, because I’ve heard that story before and you’re leaving out a funny element: that Besser apparently gave you a packet of sketches.

Besser: Oh, yeah—I wrote all these sketches for my thesis in college. I liked Walsh, and offstage [at the Roxy] I was like, “Hey, read my sketches; let’s do these.” I think you didn’t respond. You never read them, right?

Walsh: No, I never read them. And then you were like, “Dude, can I get my sketches back?” That was in the day when sketches were your scripts, sort of.

Besser: I had to drive 30 miles to get to a printer. Give me my fucking sketches back, man.

Walsh: I felt not great about that. Is this phone call about getting the sketches back?

Besser: I’ll meet you in the parking lot.

Roberts: The first time I was around [you two] was probably a year after you met. I met Matt Besser; we ended up on a team together at the ImprovOlympic, which was an improv theater in Chicago. Matt Walsh and I ended up in the same touring company at Second City.

Besser: The improv scene was at its nascent moment when we joined. It exploded over those next few years, but it was kind of small at that point. If you were interested in improv, you knew everybody. It revolved around ImprovOlympic and the Annoyance Theatre, with everybody having dreams to be in Second City.

Roberts: When all of us ended up working together—Matt Walsh, Matt Besser, and myself—it was kind of in opposition to Second City. Second City was perceived by most of us as being a little staid and it was hard to break into.

Besser: Kids in the Hall was real popular right then. They were definitely my favorite group, and seeing them get a TV show was inspirational to groups like us. Most people either want to be on SNL or have their own sketch group, and we were on the path of having our own group. Maybe that did make us tighter, because we were united in a long-term goal.

Roberts: A lot of the aesthetic of our shows was anti-authority. Back then, there was this [practice] of being a dishwasher or working the door at Second City and you could work your way up. Fuck all that; I’m not going to hang around and be a toady at this place. I’m going to do my own thing. They had a nice theater, and we’d be in some crappy café with no food license. [Second City] was the place where everyone from the suburbs and out of town came. We were for the kids who were living in Wicker Park apartments with no heat, who had no money.

Beck: This is sort of a chicken-or-the-egg question—

Walsh: Chicken.

Roberts: You have to do the question, Matt.

Walsh: Oh, sorry.

Beck: Did the friendship come as a result of working together, or was the working together a result of the friendship?

Roberts: For me, the friendship was a result of working together. The first time Matt Besser walked up to me and said, “Hey, you want to be part of a sketch group?” I was, like, medium [about it]. I was like, “Yeah, sure.” I got to know you guys from working with you, really.

Besser: I think the improv community is pretty unique. Not only have many long-lasting friendships come out of it, but also marriages—including my own, Ian’s, and Walsh’s. “Working” doesn’t even describe it. It’s beyond work, because you’re sharing an artistic thing together. You’re sometimes sharing dreams together, like we did: the goal of a sketch show on TV. Work is maybe 9 to 5, but with improv, you’re not just hanging out when you’re onstage. You’re going to the bar afterward, and it becomes a lot deeper than that.

Roberts: It’s also huge for developing that shared sensibility. There’s this term that describes how we tend to interact offstage and it’s doing bits. That’s what we would try to encourage our students to do—you’ve got to be hanging out. That’s how you get great. You start to know each other’s rhythms. It is 24/7. You’re always either rehearsing or performing or hanging out. And while you’re hanging out, you’re practicing your chops without trying to.

Besser: Ensembles and friendships grow hand in hand. The first time, you’re put together by a director, but then as you grow as a comedian you start to make your own choices. You’re like, I want to perform with that person, or This person isn’t jiving with our group; they need to leave. So friendship becomes an important part of the ensemble, too.

Roberts: Besser and I were put on a team together, but we kind of jived better with some other people. Besser came to that realization earlier than I did. He told the woman who ran the organization, “Look, I want to get off this team and go on this other one.”

Besser: At the end of the show she gathered all the teams together and said, “Matt Besser has an announcement.”

Roberts: She put him in the awkward position of having to give this fake heartfelt speech about, “Guys, I love performing with you, and we’ve got this chemistry. But sometimes there’s another chemistry. The reactions are stronger over there, and so you move on.” It was like, What the fuck is he talking about? I met with him afterward and he goes, “I didn’t want to give any speech! She blindsided me.” Shortly after that, I left and joined that team. That was a bunch of the guys that ended up doing Upright Citizens Brigade.

Beck: I want to hear a little more about how the way improv works intersects with friendship. For instance, do you think it’s possible to do a good show with people that you aren’t really friends with?

Walsh: Definitely.

Roberts: It is. Because there are these rules, and if you’ve been taught well, you all know the same rules. So you hit the ground running. I’ve performed with these younger improvisers who I don’t know well and it’s funny because it does feel like you’re friends. What do friends do? Friends have a shorthand and they goof around. You get onstage with these people and you have that shorthand. It’s a taught shorthand, but after one show it feels like you’re a bunch of good friends.

Walsh: I think you do have to like the people, or else you can’t really improvise with them. I’ve seen a little bit of natural selection. I’ve seen shows as a fan where I’m like, Oh, that poor guy got stuck with that person. You can feel it.

Besser: I agree with you; there’s no way you can be on a team with anybody you despise. But I can think of people who didn’t hang after shows but were proficient onstage. Long term, it’s not about what’s happening onstage as much as what’s happening in the greenroom. Like, Why is he always giving everybody notes? Or, When we go on tour, why does he act like he’s the boss? That kind of drama.

Roberts: I had a funny situation, and I won’t name names, but in my early days of improv, I didn’t know the way the organization worked. One day I said, “You know that guy who’s the captain of my team?” And Besser said, “What are you talking about?” I said, “The guy who’s in charge and gives notes and everything.” He goes, “Dude, there’s no captains of teams.” It was like a veil dropped.

Besser: He’s not the captain; he’s the asshole of the team.

Roberts: Once I knew that, I went from being neutral toward this guy to hating his guts.

Beck: Could you take me through the different eras of UCB? Chicago, New York, etc.? Did those coincide with different eras of your friendship?

Besser: UCB was simultaneous with when we were doing improv. It was all happening at the same time: getting involved in improv, doing stand-up, developing a sketch show. That was the early ’90s.

Roberts: For the longest time, it seemed like all the shows kind of felt like art for art’s sake and to hell with them being marketable. I think of this one show, “Thunderball,” that was a reaction to the [1994] baseball strike. We created a sport that was an alternative to baseball. It was this experience; we went out on the street.

Besser: We went in front of Wrigley Field and protested.

Roberts: At a certain point, when the group coalesced into the cast that ended up on TV, I guess we were just getting to the age where you had to think, Okay man, someday we got to enter the grown-up world. We’ve got to make money for this stuff.

Besser: We had to get serious, and that’s when we decided to move to New York.

Roberts: The four of us. It’s Amy [Poehler], Matt Besser, Matt Walsh, and me. At that point, we made a promise to each other. You can go do a commercial, you can do a day at work on a show, but don’t anybody go taking a regular [role] on a sitcom, because we’re committed to each other. That’s why a lot of groups can’t succeed. They get cherry-picked; they don’t make a commitment like that. It was rough for different people for different reasons. Matt Walsh, his whole family was in Chicago. And Amy Poehler had a pretty solid offer to get on the main stage at Second City.

Beck: What were the terms of the agreement? Was it time-delineated?

Roberts: It was indeed. I think it was a year.

Walsh: I think it was shorter. I think we said, “Let’s give New York six months and we’ll revisit this conversation.” Then we never revisited it. We just started having success.

Beck: Once you were in business with your close friends, how did that change things?

Besser: We never really entered it as a business, but it certainly became that. At the time, everything was very low stakes. It was more this organic, gradual growth that we experienced together. We never counted on it to be a living business for us. It was more like a hobby and a community.

Roberts: We found a former strip club that got put out of business because Rudy Giuliani was cracking down on all the red-light stuff. We had no money. We took [the strip club’s] runway stage, chopped it up, made it into a regular stage, and turned a club into a theater. We put shows up there that would make just enough to make the rent.

Nowadays, you come into an organization and you’re not necessarily going to feel this incredible bond with everyone instantly. Back in the day, you did, because you were all involved in the same struggle. There’s no construction team putting this theater together. It’s, Everyone show up, bring tools, help us build this theater.

Besser: Literally. You’re not speaking figuratively. It’s closer to a barn-raising than opening a business.

Roberts: There wasn’t a lot of stress, because we were too stupid to know that there should’ve been stress.

Beck: At what point did it stop feeling like this scrappy random thing that you guys were doing with your friends and become something bigger?

Roberts: I’d say when our [first] theater closed. We fell into that; it was available because of the Giuliani thing. It got closed down, so we regrouped and started this [other] theater, which became the one we were in for, like, 15 years. We had to make a real commitment to keep going. At that point it was like, Is this the end, or do we figure this out? For me, it felt like a step forward to getting serious.

Walsh: I think for me [it was] the L.A. theater opening. Having places on two coasts was the thing that made me feel like, Oh, this is grown-up.

Besser: To me, it was when I gave my senior thesis, of which there was only one copy, to Walsh and never got it back.

Walsh: I don’t save paper anymore; everything’s shredded. I don’t know what to tell you.

Besser: Oh, like it didn’t end up in improv on Veep.

Roberts: Matt, would you be willing, if we could hypnotize you, to see what we can get out? What you still have in there?

Walsh: No. Absolutely not.

Roberts: I think this may be the end. How are we going to get over this?

Beck: How involved are you still with UCB? How often are you still in touch with one another?

Besser: Well, we have the Del Close Marathon, which is our little comedy festival that we’ve kept alive for 21 years. That’s a ritual we do every year. It’s obviously a challenging thing to pull off, but it’s also exciting because you get to see people you often don’t see, even though you live in the same town, you work in the same business. It’s like our summertime Christmas.

Walsh: That is the reunion time for the theater, where everyone does come back. Many of us from the early days have moved on and have families and kids and all that. So you don’t have the free time you did in your 20s to hang out.

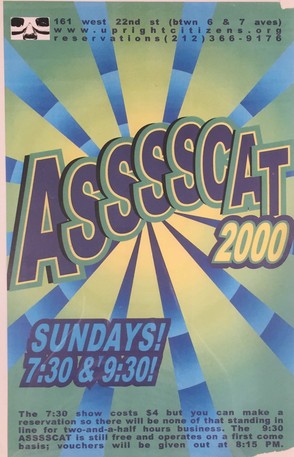

Roberts: We’ve [also] been doing a show called “Asssscat,” which is a show for veterans to get together. It’s like pickup basketball and it’s been going forever. We’ve always kept in touch through that show. For me, it’s the only show I’ve remained involved with all throughout the years no matter what else I’ve done. I saw Walsh this past weekend there.

Beck: Does it feel different when you guys perform together, as opposed to other things you work on?

Besser: I think Ian’s point earlier about shorthand really describes the uniqueness of friendships that come out of improv. As the years go by, that shorthand can only grow.

Beck: Do you three have any particular shorthands that come to mind?

Walsh: I get frustrated when Ian doesn’t know how to play games. He can’t be playful in a formalized way. It’s always off; you’re always trying to handle him.

Besser: That sounds like a criticism more than a shorthand.

Roberts: [My problem] with Matt Walsh is, he completely understands the form but he’s not intrinsically funny. But that’s what’s interesting about the relationship, right?

Besser: Maybe we don’t know what shorthand means.

Beck: Yeah, maybe not. I meant phrases or inside jokes.

Besser: When you hang with people a lot, there are unconscious tendencies you can anticipate. You can play to their strengths.

Roberts: If I’m onstage with people I’ve been performing with for 20-some years, like Matt Walsh and Matt Besser, I don’t even need to count on one hand how many times something has been missed. You just don’t miss stuff. You know exactly what you want. When you initiate a scene, it’s like Legos. I need you to be the other side of this. And you’re like, I got it; you want me to be a straight guy and be frustrated by this thing you do. I never get left hanging.

Besser: That’s something anyone can understand as a friend. The closer you are, the longer you know someone, the more you know what they want. And that applies to our improv forms too.

Walsh: A lot of Ian’s scenes are about Legos. Most of them. Lego-based comedy.

Besser: We know he can only make a metaphor if it involves Legos.

Beck: Well, that’s probably big with your kids right?

Besser: That’s why he had kids.

Roberts: You see how that worked, though? I made my comment, and just like a Lego, it let them take it to this level where they describe the way that I work.

Beck: How have you guys seen the broader improv social scene change over the years?

Walsh: It was a very small community when we started and very homogenous. Now it’s really diverse, at least in the New York and L.A. scenes at UCB.

Besser: That’s a great point. With that team we were telling you about earlier that formed as an improv group, not only were we all straight men and five of the six of us white, but I’m pretty sure we were all over 6 foot 2.

Roberts: Amy talked about that in her book. She described our team and she said [something like], “They were giants of improv,” and she says, “I mean that literally.”

A slight difference is, I felt like everybody knew everybody when we first started UCB. The bond was so tight. Everybody helped build the theater; it was very small, 30 or 40 people. That’s lightning in a bottle. This is almost one tribe of people. There’s probably [multiple] groups like that of 30 or 40 within our organization now. You cannot have as much buy-in. It becomes a little more abstract. There gets to be a little bit more distance between you and [other] people in the organization, I think.

Beck: Was there anything else you wanted to mention about your friendship, improv, or grievances you wanted to air?

Roberts: The main one has been brought up. Walsh has to make a decision of what he’s going to do. You’ve got someone’s scenes, Matt.

Besser: Intellectual property.

Walsh: I guess I have to ask why was I entrusted with the master copies. Why is that my burden?

Besser: That’s easy to say now. That was back in the day. Why weren’t there two Declarations of Independence?

Roberts: I don’t think that’s a grandiose analogy. Matt is a very good scene writer. You basically had the equivalent of the Declaration of Independence in sketches.

Walsh: I just don’t think they exist anymore and I don’t remember—

Roberts: I know we’ll continue to be friends and work together, but you need to hear this. Shame on you, Matt Walsh; shame on you.

If you or someone you know should be featured on The Friendship Files, get in touch at friendshipfiles@theatlantic.com and tell us a bit about what makes the friendship unique.