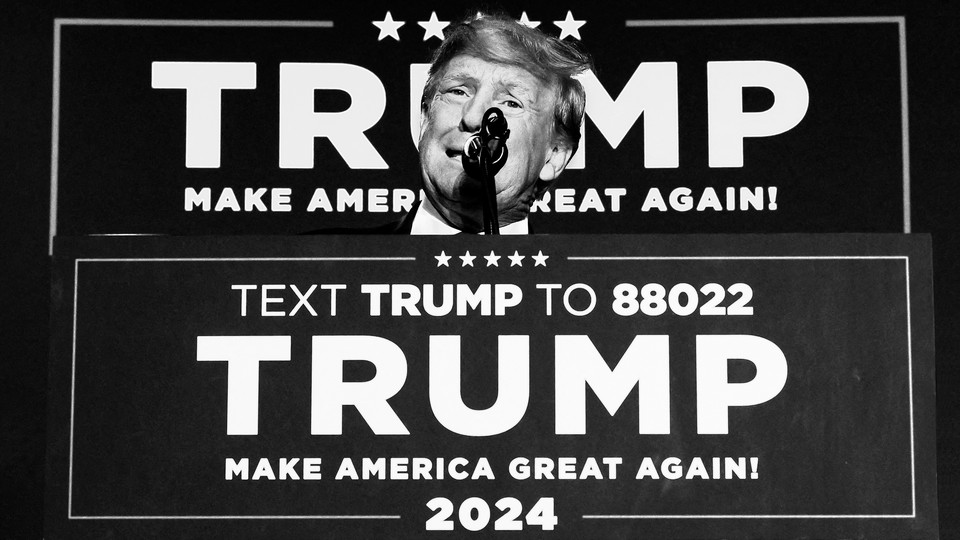

The First Great Crisis of a Second Trump Term

If reelected, the former president would move to make his legal troubles disappear. Constitutional chaos and political mayhem would ensue.

Both his supporters and and his opponents assume that former President Donald Trump’s legal jeopardy will go away if he can win the 2024 presidential election. That’s a big mistake. A Trump election in 2024 would settle nothing. It would generate a nation-shaking crisis of presidential legitimacy. Trump in 2024 means chaos—and almost certainly another impeachment.

Trump’s proliferating criminal exposures have arisen in two different federal jurisdictions—Florida and the District of Columbia—and in two different state jurisdictions, New York and Georgia. More may follow.

As president, Trump would have no power of his own to quash directly any of these proceedings. He would have to act through others. For example, the most nearly unilateral thing that Trump could try would be a presidential self-pardon. Is that legal? Trump has asserted that it is. Only the Supreme Court can deliver a final verdict, which presents a significant risk to Trump, because the Court might say no. Self-pardon defies the history and logic of the presidential-pardon power. Would a Supreme Court struggling with legitimacy issues of its own take such a serious risk with its reputation to protect Trump from justice?

Trump has one way he might avert the hazard of the Supreme Court ruling against him. He could order his attorney general to order the special counsel not to bring a case against his self-pardon, and then order the Department of Justice to argue in court that nobody but the special counsel has standing to bring a case.

Then things get complicated. Would the attorney general do it? Would the special counsel submit? Would the professionals in the Department of Justice stay in their jobs? And what would happen in Congress and in the country?

The situation becomes even more complicated if you assume that Trump couldn’t win a majority of the popular vote (given that he has twice failed to win one). If he returns to office, he’d most likely do so thanks to a fluke in the Electoral College.

So a criminally indicted president would have to argue that he’s entitled to self-pardon, and also that he’s entitled to forbid the prosecutors to challenge that in court, and also that he can order his Department of Justice to fight in court against anybody else who seeks to sue in the prosecutors’ stead. He’d have to do all of this based on a claim that he represents the will of the people, even though he likely did not win a majority of the popular vote.

And after all that, he’d still face indictments in state courts, where he has no pardon power. So, for his next move, he would have to order the Department of Justice to argue that state courts have no criminal jurisdiction over a serving president. He could shoot someone on Fifth Avenue in New York City, or on the street in any state, and nobody could do anything about it until his term was up, if then.

As the absurdity of this situation would play out, it’s probable that within a couple of days of an attempt at self-pardoning, Trump wouldn’t have a Department of Justice. There would be mass resignations, and probably no way to confirm replacement senior officials in the U.S. Senate. (The first Trump administration repeatedly relied on acting appointees rather than on Senate-confirmed officials, but a second administration intentionally bypassing the Senate in order to shut down the courts would invite a constitutional crisis all of its own.)

Trump’s other routes to the same destination run into the same problems. Trump could try a more indirect maneuver to shut down the federal indictments: Order Special Counsel Jack Smith to stand down, and fire him if he refuses. That approach bypasses the courts, but it depends even more heavily on finding a compliant attorney general to cancel the indictment, and on the acquiescence of Congress in what would look like an outright nullification of federal law enforcement. The federal Department of Justice would dissolve. The state cases would continue regardless. Trump scandals would be the only order of business in Congress.

Trump himself may not care: He was neither chastened nor deterred even by impeachment. But Trump leads a minority faction in the country, and the kind of permanent crisis a second presidential term would generate would invite a 2026 Democratic congressional landslide big enough to jolt even a Trump-led GOP.

Trump may imagine that he’s got a one-and-done fight on his hands: Strike hard, strike fast, then settle back to enjoy the corrupt perquisites of lawless power. If so, he and his followers are deluding themselves. The entire term would be consumed by the battle over Trump’s project to use the power of the presidency to protect himself from the consequences of his alleged crimes.

Trump’s past practice when in trouble was to deflect attention from one scandal by lurching into another scandal. Maybe this time he’d try to cut off aid to Ukraine or blow up NATO or start a culture war against drag queens. But none of those stunts would distract Americans; they would only embitter them.

A Trump bid for self-pardon would not be the equivalent of President Gerald Ford pardoning former President Richard Nixon, a decision unpopular at the time but ultimately accepted by many of its fiercest critics as well as a majority of the public. A self-pardon attempt would convulse the country. It would never gain acceptance as a legitimate act undertaken for public-spirited, bipartisan ends. The furor would not subside; the constitutional injury would not heal.

A second Trump presidency would offer only division, chaos, and paralysis that would never be quieted. Nor would it cease—until that presidency itself ceased, and perhaps not even then.