The State Election That Could Change Abortion Access in the South

In North Carolina, the Democratic governor might lose his power to stop the GOP’s legislative agenda.

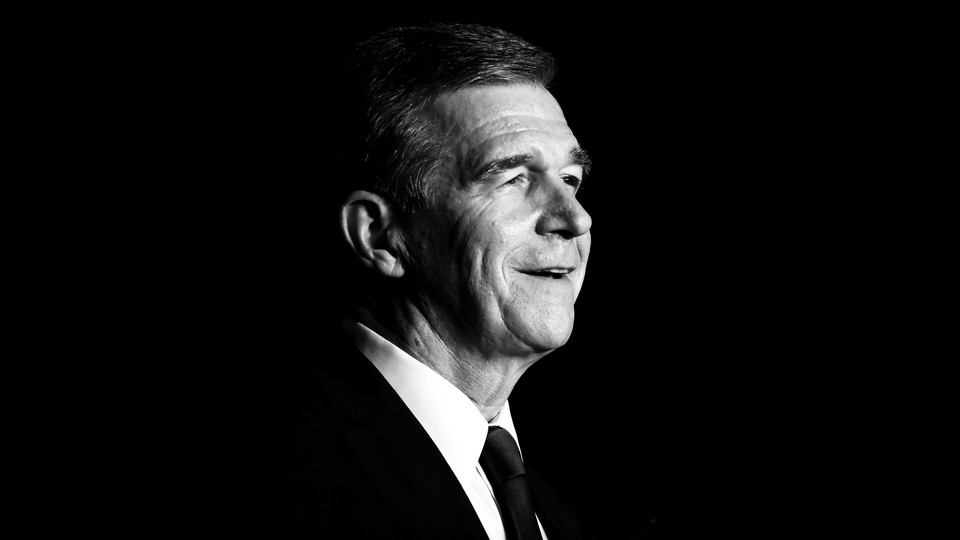

DURHAM, N.C.—No North Carolina governor has ever wielded the veto like Roy Cooper.

The Democrat has vetoed 75 bills in his nearly six years as governor. That’s more than twice as many as every other governor in the state’s history combined. Since its earliest state constitutions, the Old North State has been skeptical of executive power, and the governor only gained veto power in 1996. Cooper is the first governor to seize its full potential.

Cooper has rejected bills to require sheriffs to cooperate with Immigration and Customs Enforcement, to open skating rinks during the early months of the coronavirus pandemic, to loosen gun laws, and to tighten voting laws. He has also vetoed bills to restrict his own office’s powers.

The power is not absolute. As in Washington, a supermajority can override the veto—in North Carolina, three-fifths of both chambers of the legislature. Until 2018, Republicans held more than the 30 Senate and 72 House seats they needed to override the governor, and they did: In his first two years as governor, Cooper vetoed 28 bills, but 23 of them were overridden. Two years later, Democrats cut into Republicans’ margins, and since then, every veto has been sustained.

The balance of power in the North Carolina General Assembly is up for grabs in this year’s election. Politicians and experts on both sides of the aisle agree that the real battle is not over whether Republicans can maintain control of the legislature but over whether they can reclaim a supermajority. The GOP needs to win just two seats in the Senate and three in the House to do that. Whether it succeeds will have major implications for the direction of the state, which has often served as an incubator for conservative governance. But the answer could also be pivotal for an even bigger question: how available abortion will be in the region. Most states in the Southeast have abortion laws that are generally more restrictive than North Carolina’s, making the state a magnet for women seeking access—at least for now.

“I’m not personally on the ballot,” Cooper told me. “My ability to stop bad legislation is. The effectiveness of the veto is on the line.”

That is a rare point of agreement for Cooper and Republican leaders. “The Democrats will not get a majority in either the North Carolina House or the North Carolina Senate,” Phil Berger, the president pro tempore of the State Senate, a Republican, told me. “So then the question becomes what’s going to be the level of Republican control within the general assembly … [and] whether or not the governor’s veto is something that will have any real bearing on legislation.”

State legislative elections have long been treated as a parochial backwater, but in this cycle some of them have vaulted to prominence thanks in large part to battles over election administration, as Donald Trump acolytes and election deniers seek to take over the mechanisms of voting. National money and attention have flowed into states such as Michigan, where control of the legislature is up for grabs, and with it the fate of elections in a key swing state, as my colleague Russell Berman recently reported.

For more than a decade, North Carolina has been the site of a series of pitched battles over both voting laws (voter ID, poll hours, and more) and redistricting, often with GOP legislation being struck down by state courts or federal judges, who famously found that a voting law targeted Black voters “with almost surgical precision.” The U.S. Supreme Court is currently considering a case that originated in North Carolina over the “independent state legislature” theory, and the justices’ decision could render state legislators’ power over elections nearly uncheckable.

Voting is a leading issue in North Carolina this year, too. Cooper has repeatedly vetoed Republican attempts to make voting harder, but the governor doesn’t have the power to veto maps, so whether Republicans have a supermajority does not substantially affect how this will play out. (North Carolina voters will also decide whether to hand control of the Democratic-majority state supreme court, which has rejected previous maps, to Republicans.)

Abortion laws, however, are one area where the veto could make all the difference—and one whose importance could extend beyond state lines. As in many campaigns across the nation, Democrats are seeking to capitalize on backlash against the Supreme Court’s decision overturning Roe v. Wade to make the election a referendum on abortion.

“We know that North Carolina has been a safe haven for women’s reproductive freedom,” Cooper told me. “When you talk to women’s-reproductive-health providers in North Carolina, they will tell you that the number of out-of-state patients has increased dramatically. We have people coming from Georgia and South Carolina. We even have had people come in from East Texas to get women’s health care. And it is critical to have this safe haven in the Southeast.”

Abortion is currently banned in the state, in most cases, past 20 weeks of pregnancy, and Cooper has vetoed more-restrictive laws. South Carolina last year moved to ban most abortions after six weeks (though the law is currently blocked in court), which is also the law in Georgia. Florida does not allow abortions after 15 weeks, and every other southeastern state has a full ban, with very limited exceptions.

Democrats say that without Cooper’s veto standing in the way, a Republican supermajority would quickly follow surrounding states in enacting either a complete abortion ban or something close to it. They note that GOP members have in the past introduced bills to ban abortion completely or once a heartbeat is detected, something the speaker of the state House says he supports. Some Republicans, meanwhile, have followed their national counterparts in mostly trying to downplay the issue.

“You’ve seen Republican candidates and Republican legislators trying to moderate their positions on abortion to gain election,” Cooper told me, adding, “My message is: Don’t believe them.”

Berger scoffed at the idea that his caucus would seek an abortion ban and said Cooper undermines his own credibility by saying it, though he acknowledged that some members have pushed for bans. “I daresay that the people they point to who have introduced a bill are people that generally don’t get bills passed,” he told me.

Republicans, meanwhile, say voters’ central issue will be dissatisfaction with President Joe Biden’s stewardship of the economy and, in particular, inflation. Paul Shumaker, a veteran GOP consultant, warned in a recent memo that abortion threatened to cut into Republican gains, but he still thinks Democrats will struggle to win on that alone. “If the Democrats try to make it a singular issue around abortion, it’s because they’re ignoring the inflation and the anger,” he told me. “Abortion, to me, is not an overriding issue like the economy. Republicans need to not let it become one. The way Republicans lose is if they let it become a referendum on a ban.”

Cooper has put his muscle into the legislative race, holding dozens of fundraisers for legislative candidates and cutting an ad for one Democratic candidate focused on the veto. North Carolina is sharply politically divided between rural and urban voters, who consistently vote Republican and Democratic, respectively. Whether Republicans regain the supermajority in the Senate will be decided in suburban and mixed districts around big cities such as Charlotte and Raleigh. In many of those districts, Democrats are running women, many of them women of color.

These battleground districts have changed rapidly in recent decades and years, part of a wave of in-migration to North Carolina. About half of all adults in the state were born somewhere else. State Representative Rachel Hunt, who won election by just 68 votes in 2018, is now looking to move up to the Senate. She’s the scion of a venerable political family—her father, Jim Hunt, was governor from 1977 to 1985 and 1993 to 2001, and the first to have veto power—but she told me that many voters she canvasses are barely aware of the state legislature, much less familiar with her family name. State Senator Sydney Batch, who is running in a district outside Raleigh, says her neighbors joke that she’s the only person on the street who’s actually from North Carolina.

Mark Cavaliero, the Republican running against Batch, hopes that economic concerns will lead people to vote GOP. “If you look at inflation, you know, you look at mortgage rates, you look at the value of your 401(k)—those things are all dropping, and it’s causing people a lot of pain,” he told me. (“My voters can fortunately walk and chew gum, and they are concerned about more than just inflation,” said Batch, a former state representative who was appointed to the seat and is now running for election there for the first time. “They’re concerned about the environment; they’re concerned about choice.”)

Many of these contested districts are full of moderate professionals—unaffiliated voters typically represent a plurality—who have traditionally leaned Republican but began to shift toward Democrats during the Donald Trump years. Now Democrats hope that anger about abortion will fire them up the way Trump did.

“I don’t know what could happen between now and November to make things different, but I don’t think women are going to settle down and not vote in November; they really are going to turn out,” Hunt said. “And that is exactly what the Democrats need to be able to hold on to the urban areas and make some inroads in the areas right outside of the urban areas.”

Even though midterm elections are typically difficult for the president’s party, the consensus is that the general-assembly battle will remain close until Election Day. Cooper gave Democrats a 50–50 shot at preventing the supermajority, and Morgan Jackson, a Democratic strategist close to Cooper, told me, “Six months ago I think [Republicans] would have [won] supermajorities in both chambers. Now I’m optimistic, but I think it’s going to be very close.” On the other side, Berger is optimistic too: “I’d much prefer to be in our position than their position,” he said.

Whatever the outcome of the races this year, the next cycle will likely be just as hard-fought and close, like every election in North Carolina these days. “Bottom line is, this is very much a swing state, and if Republicans have a great night in 2022, no one should read any indicators into that about what 2024 is going to look like,” Shumaker warned. But even if no majority—or supermajority—is permanent, the consequences for voting and abortion laws will be real.