The 1950s and 1960s witnessed a seismic shift in the landscape of cinema, an uprising whose effects can be felt to this day. Emerging from the ashes of a post-war France grappling with social and cultural upheaval, an audacious group of filmmakers challenged the very foundations of traditional cinematic storytelling, ushering in a new era of bold experimentation and uncompromising artistic expression. Known as the French New Wave (Nouvelle Vague), it became a major force in world cinema, leaving an indelible mark on film history.

Born out of a dissatisfaction with the staid, formulaic films of the past, the New Wave filmmakers were ardent cinéastes. They were deeply influenced by the works of classic Hollywood directors like Alfred Hitchcock and film noir masters, as well as by the innovative techniques of European directors like Federico Fellini and the Italian neorealist movement. This admiration for cinema’s past fueled their desire to break free from established norms and forge a new path.

Rejecting the studio system and its rigid production processes, the New Wave filmmakers championed a more independent approach. They embraced low budgets, readily available equipment, and a focus on on-location shooting. This allowed them to capture a raw, authentic style that resonated with a younger generation. The post-war world and the rise of youthful counterculture fueled a spirit of rebellion and a questioning of traditional values, feeding into the thematic concerns of the New Wave films. The May 68 protests in France, a period of student-led worker strikes and demonstrations, coincided with the French New Wave’s peak. While not a direct cause-and-effect relationship, the events resonated deeply with the movement’s spirit as films explored themes of political unrest, questioning established power structures, and challenging societal norms – ideas that mirrored the students’ demands for change.

In this article, we explore 15 of the greatest films to emerge from the French New Wave, each of them marking a revolutionary cinematic chapter in the unique ways in which they reimagine filmmaking praxis.

1. La Pointe Courte (1955)

Directed by Agnès Varda, “La Pointe Courte” is a landmark film that somewhat predates the French New Wave movement while embodying many characteristic themes and techniques. This poignant and reflective film, telling the story of a disintegrating marriage set against the backdrop of a small French fishing village, has been hailed by film critic and historian Georges Sadoul as being “truly the first film of the nouvelle vague.” Elle (Silvia Monfort), a former opera singer, returns to her husband’s village, La Pointe Courte, after a prolonged absence. As they attempt to rekindle their relationship, they are confronted by the harsh realities of their own disillusionment and the struggles faced by the locals. The husband, Lui (Philippe Noiret), yearns for a simpler life while his wife grapples with boredom and a sense of displacement amidst the close-knit community.

Rather than relying on contrived plot devices or melodramatic confrontations, Varda allows the narrative to unfold organically, mirroring the ebb and flow of everyday life. The mundane conversations, prolonged silences, and fleeting glances between Lui and Elle speak volumes about the fractures within their relationship. Anticipating the oncoming nouvelle vague trend, Varda utilizes non-professional actors from the village, lending an air of authenticity to the portrayal of working-class life. The handheld camerawork imbues the film with a sense of immediacy, capturing the bustling activity of the harbor and the intimate conversations within homes. This approach starkly deviates from the polished studio films that dominated the era, foreshadowing the New Wave’s emphasis on handheld cameras and location shooting.

2. Elevator to the Gallows (1958)

Louis Malle’s 1958 film is a masterfully crafted neo-noir that not only enthralls with its suspenseful plot but also serves as a pivotal entry point into the burgeoning French New Wave movement. The film plunges viewers into the Parisian underworld, where a meticulously planned murder spirals into a nightmarish chain of events. The film revolves around Florence Carala (Jeanne Moreau), the wife of a wealthy industrialist, and her lover Julien Tavernier (Maurice Ronet). The two conspire to murder Florence’s husband, Simon (Jean Wall), but their carefully laid plans unravel when Julien gets trapped within the building’s elevator during a power outage. Meanwhile, a young couple, Véronique (Yori Bertin) and Louis (Georges Poujouly), stumble upon Julien’s abandoned car, which they steal and assume his identity, leading to a chain of misadventures that take them all to the gallows.

Malle embraces a documentary-like realism, eschewing the polished veneer of mainstream cinema in favor of a gritty handheld camera style that lends authenticity to the proceedings. The city of Paris itself becomes a character, with Malle’s camera capturing the neon-lit streets, seedy cafes, and the pulsating underbelly of the urban landscape with its unflinching gaze. Beneath its surface as a taut crime thriller, “Elevator to the Gallows” also explores profound existential themes that resonated with the philosophical underpinnings of the New Wave movement. Julien’s entrapment in the elevator becomes a metaphor for the human condition, a reflection on the isolation and alienation that permeates modern society. The film’s characters are portrayed as adrift in a world devoid of meaning, grappling with questions of morality, desire, and the fleeting nature of existence.

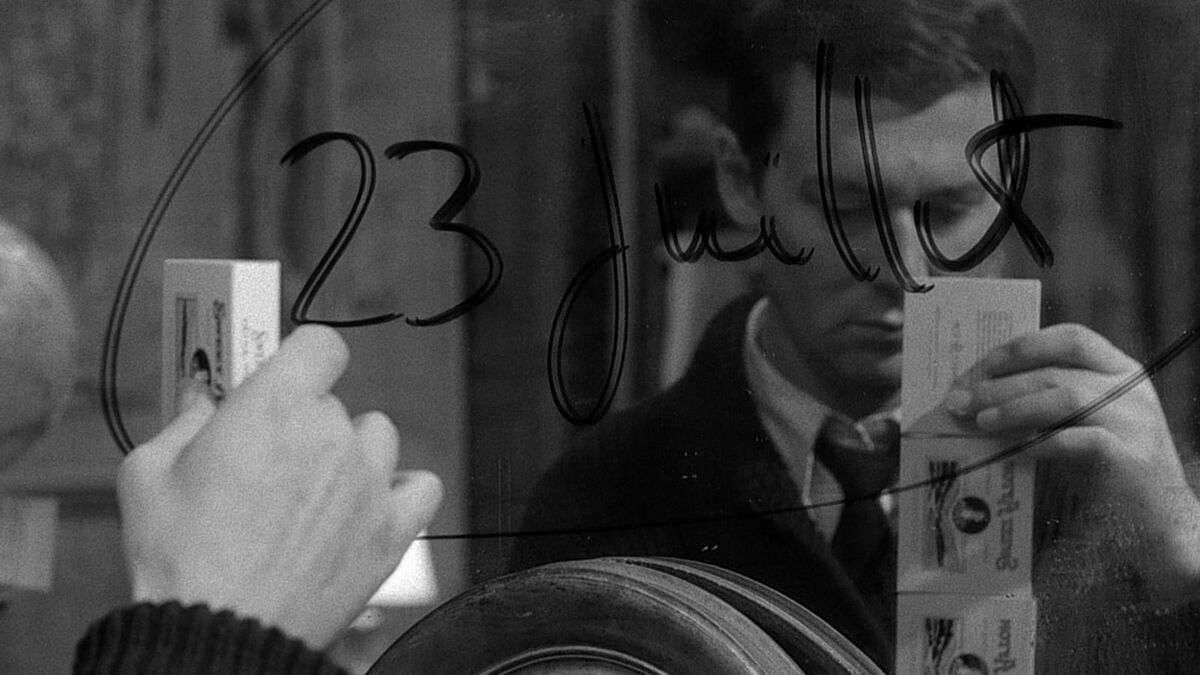

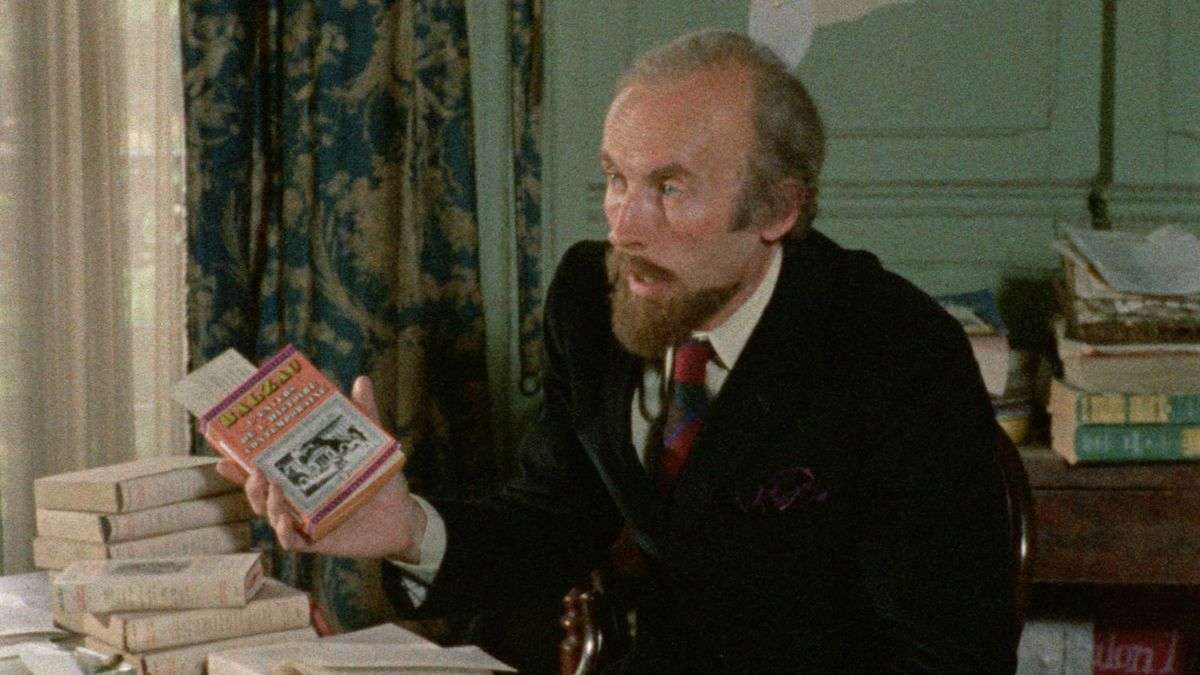

3. The 400 Blows (1959)

One of the most famous films of the New Wave, Francois Truffaut’s debut film is a coming-of-age story that chronicles the struggles of Antoine Doinel (Jean-Pierre Léaud), a restless young boy grappling with a neglectful family and an oppressive school environment. Through Antoine’s experiences, the film critiques societal indifference towards childhood problems and the stifling conformity of post-war France. Neglected by his emotionally distant parents – a preoccupied mother and a stepfather with whom he has little connection – Antoine finds solace in skipping school, committing petty theft, and daydreams of adventure. His classroom becomes a battleground against a rigid and unsympathetic teacher who fails to recognize his potential.

Whether it’s writing a poem on the classroom wall or plagiarizing an essay from Balzac, Antoine’s acts of defiance stem from a yearning for connection and a desire to escape his suffocating reality. We see Antoine’s frustration bubbling over into anger, his loneliness manifesting in mischievous pranks, and his fleeting moments of joy dissolving into despair. Truffaut masterfully captures the raw emotions of adolescence and challenges the romanticized portrayal of childhood that dominated classical French cinema. A cornerstone of the French New Wave, “The 400 Blows” ends on a particularly poignant note, with Antoine having run away from home and finding himself on a beach, the vastness of the ocean mirroring the uncertainty of his future. The freeze-frame on his face captures a complex mix of emotions: defiance, fear, and a glimmer of hope – which aptly represent the rebellious spirit that was characteristic of the nouvelle vague.

4. Hiroshima Mon Amour (1959)

Set in the recently rebuilt Hiroshima, Alain Resnais’ 1959 film weaves together a passionate love affair between a French actress (Emmanuelle Riva) and a Japanese architect (Eiji Okada) with the devastating legacy of the atomic bomb. With the screenplay penned by Resnais’ fellow Left Bank auteur Marguerite Duras, “Hiroshima Mon Amour” follows the French New Wave characteristic of defying linear storytelling and instead featuring a complex narrative woven together from fragmented conversations and dreamlike flashbacks. The film’s opening sequence, a breathtaking montage of intertwined bodies and haunting imagery, sets the tone for a work that challenges conventional notions of time and space. The couple’s passionate encounters are interspersed with haunting black-and-white documentary footage of the bombed city, forcing viewers to confront the devastation wrought by war.

Resnais’ innovative editing techniques further blur the lines between past and present. Scenes seamlessly shift between the lovers’ encounters in Hiroshima and flashbacks to their respective wartime experiences. This fragmented structure reflects the characters’ own difficulties in trying to piece together fragmented memories and forge a connection in a world forever altered by war. With the past constantly intruding upon the present, the narrative mirrors the characters’ struggle to reconcile their burgeoning love with the weight of their respective histories. The film’s visual style further exemplifies the New Wave’s embrace of handheld camerawork and unconventional framing. Resnais’s camera lingers on the smallest details – the curve of a body, the flicker of an eyelid – imbuing the film with a profoundly sensual and visceral quality that heightens the emotional resonance of its subject matter.

5. Breathless (1960)

Godard’s audacious and unconventional debut feature, “Breathless,” not only heralded the arrival of a visionary filmmaker but also challenged the very foundations of traditional cinematic storytelling, bringing widespread international attention to the French New Wave phenomenon. The film follows the exploits of Michel Poiccard (Jean-Paul Belmondo), a charismatic car thief who styles himself after Humphrey Bogart. After stealing a car, Michel shoots a police officer and flees to Paris, where he reunites with his American girlfriend, Patricia Franchini (Jean Seberg).

The narrative unfolds over a breathless two-day period as the couple’s whirlwind romance, simultaneously passionate and volatile, becomes the backdrop for Michel’s desperate attempt to escape to Italy. Michel’s character embodies the rebellious spirit of the New Wave. He’s a product of post-war disillusionment, a James Dean-esque figure who idolizes American film icons like Bogart. His defiance of authoritarian figures and disregard for societal norms resonate with a youthful audience yearning for change. Belmondo’s captivating performance, characterized by his nonchalant swagger and an air of existential cool, cemented his status as a New Wave icon.

Godard’s innovative approach to storytelling is evident throughout the film, as he seamlessly weaves together jump cuts, long takes, and bold experimentation with sound and editing techniques. The result is a cinematic experience that feels simultaneously spontaneous and meticulously crafted, challenging the audience’s expectations and demanding active engagement. The handheld camerawork captures the vibrancy of the Parisian streets, from the bustling cafés to the dimly lit alleyways, lending an authenticity to the proceedings that only reinforces the film’s thematic explorations of youth rebellion and anti-establishment sentiments while also reflecting the New Wave’s broader rejection of the gimmicks that had come to define mainstream cinema.

6. Cléo from 5 to 7 (1962)

Varda presents an intimate and captivating portrait of the pop singer Cléo (Corinne Marchand) navigating two excruciating hours as she awaits the results of a medical test that could reveal a potentially life-threatening illness. Cléo’s world shrinks to the confines of real-time, mirroring the French New Wave’s emergent postmodernist focus on “little narratives” and a rejection of grand, sprawling storylines. The film unfolds entirely within two hours, from 5 pm to 7 pm, as the camera relentlessly follows Cléo wandering the streets of Paris, desperately seeking solace and distraction while grappling with the possibility of her mortality, alongside her identity and the constraints of femininity. Her friends and colleagues offer well-meaning platitudes, but their attempts at comfort fall short of addressing Cléo’s profound existential anxiety.

Cléo is constantly bombarded with unsolicited advice and judgments, particularly regarding her appearance. This scrutiny echoes the objectification of women in other New Wave films like Godard’s “Bande à part” “(Band of Outsiders”), where female characters are often pawns in the male narrative. Yet, Cléo asserts her agency by ultimately embracing her natural beauty as she removes her wig, a symbolic gesture of defiance against societal expectations. Varda’s masterful fusion of personal storytelling and existential philosophy reflects the French New Wave’s broader embrace of intellectual and artistic experimentation. Her signature blend of documentary realism and cinematic artistry blurs the boundaries between fiction and reality, challenging the viewer to engage with the film on multiple levels and encouraging a critical awareness of the cinematic medium.

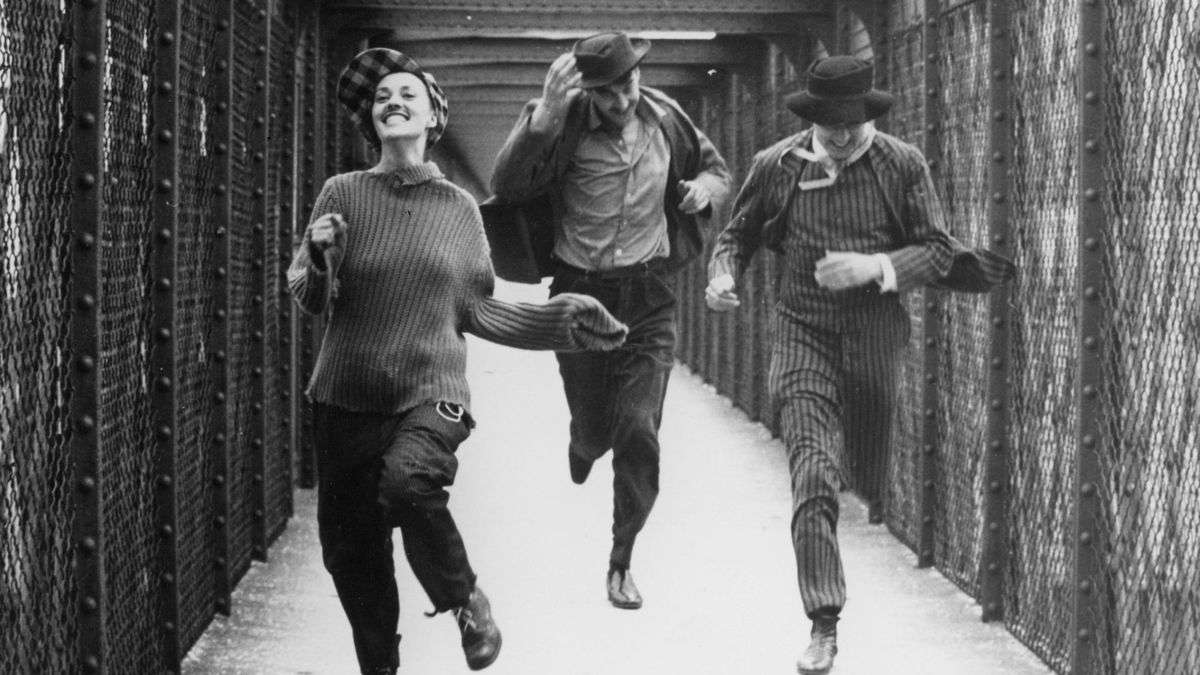

7. Jules and Jim (1962)

Truffaut’s “Jules and Jim” features a narrative unfolding across several years, beginning in Paris with the chance encounter between the reserved Austrian writer Jules (Oskar Werner) and the free-spirited Frenchman Jim (Henri Serre). Their friendship deepens with the arrival of Catherine (Jeanne Moreau), a captivating and fiercely independent woman who sparks passions in both men. Despite their initial reservations, Jules and Jim forge a pact, agreeing to share Catherine’s love in an unconventional ménage à trois. Truffaut adopts a fluid improvisational style mirroring the unpredictable ebbs and flows of life itself in a film that defies conventional narrative structures while evoking a poetic, deep humanism that differentiates it from most other nouvelle vague productions.

Defying common romantic love stories, the film embodies the burgeoning feminist concerns of the New Wave through the figure of Catherine – a woman who rejects societal expectations outright and staunchly embraces her independence. Her portrayal echoes characters like Patricia Franchini from “Breathless,” who challenge traditional notions of femininity, while the unconventional love triangle tries to reimagine the modalities of romantic pursuits without failing to depict the limitations of the same. Jealousy, possessiveness, and societal pressures soon begin to cast a shadow over the characters’ initial euphoria. The carefree spirit of the pre-war era gives way to the somber realities of a war-torn Europe, reflecting and further fracturing the fragile bonds of their relationship. Truffaut’s use of innovative camera techniques, playful visual motifs, and self-referential nods to classical cinema aptly represents the New Wave’s fascination with the possibilities of film as both an art form and a mode of personal expression.

8. The Fire Within (1963)

Centered on a stark and introspective portrayal of a man grappling with depression, addiction, and contemplating suicide, Louis Malle’s 1963 film continues the French New Wave’s preoccupation with existential themes and social alienation. Through the protagonist Alain Leroy’s (Maurice Ronet) descent into despair, “The Fire Within” becomes a gritty reflection on the disillusionment of the post-war generation. Alain is a recovering alcoholic who returns to Paris following his stay at the rehab. Despondent and devoid of hope, Alain embarks on a series of aimless encounters with old buddies and acquaintances. What he seeks is solace and connection, but finds only indifference and a sense of detachment from the social world around him.

In a particularly poignant scene, Alain attends a lavish party hosted by a former acquaintance, only to find himself an unwelcome ghost at the feast of the living. The opulent surroundings and carefree revelry further emphasize his own sense of alienation and impending doom. Alain’s former friends, consumed by their own lives, fail to recognize the depth of his despair. Unlike the handheld camerawork popularized by the New Wave, here Malle utilizes long takes and static camerawork, forcing viewers to remain vigilantly present with Alain’s emotional turmoil. Alain’s personal quest for meaning and redemption mirrors the existential dilemmas faced by many of the movement’s protagonists as they grapple with the absurdity of existence and the elusive nature of truth and authenticity in a world increasingly caught up with materialistic pleasures.

Also Related to the French New Wave: The 20 Best French Movies of the Decade (2010s)

9. The Young Girls of Rochefort (1967)

Set against the charming backdrop of the eponymous French seaside town, The Young Girls of Rochefort’s playful narrative and infectious energy exemplify the spirit of the French New Wave with the greatest aplomb. Through the interwoven stories of twin sisters Delphine (Catherine Deneuve) and Solange (Françoise Dorléac), Jacques Demy’s 1967 film offers homage to classic Hollywood musicals while injecting a distinctly new sensibility in a vibrant and whimsical musical that celebrates the yearning for love and adventure. The dance instructor Delphine longs to escape to Paris and pursue a career on the stage, while Solange, a gifted composer, craves a life beyond composing waltzes for local events and dreams of finding true love.

Demy’s visual style is a feast for the eyes. The film is awash in vibrant colors, reminiscent of classic Hollywood musicals like “Singin’ in the Rain” (1952) and “An American in Paris” (1951). The idyllic town of Rochefort, with its pastel-colored houses and bustling cafes, becomes a dreamlike backdrop for the sisters’ aspirations. Demy utilizes dream sequences and musical numbers to delve into the inner worlds of the sisters, revealing their desires and anxieties. Delphine and Solange are not passive damsels in distress waiting to be rescued. Rather, they are active agents within their own narratives, pursuing their dreams with intelligence, determination, and a healthy dose of feminine camaraderie. Their sisterly bond stands in contrast to the male characters, portrayed as charming but ultimately secondary to the sisters’ journey.

10. Le Samouraï (1967)

A neo-noir masterpiece dealing with the world of professional hitmen, Jean-Pierre Melville’s “Le Samouraï” transcends the genre conventions of classic gangster films, offering a portrait of a solitary killer navigating existential isolation and his rigid code of honor. In a film written specifically for him, Alain Delon shines as the impassive Jef Costello, a meticulous and emotionless contract killer. Living in a spartan Parisian apartment with only a caged bird for company, Jef embodies a minimalist existence devoid of attachments and with a singular focus on his work. His methodical routine as he prepares for a hit is represented via lingering close-ups of his hands assembling his weapon, cleaning his gloves, and lighting a cigarette – a ritualistic performance underscoring Jef’s professionalism and detachment.

However, following a seemingly flawless execution, Jef becomes entangled in a web of suspicion and deceit. Witnesses glimpse him leaving the scene, and the police net closes in. But Jef remains impassive throughout police questioning, relying on his meticulously constructed alibis and a signature poker face. As the investigation intensifies, Jef finds himself targeted by both the police and his employers, who fear his loyalty may waver. Melville primarily relies on static shots and longer takes, in contrast with the fast-paced action sequences of classic gangster films, forcing viewers to confront the emotional void at the protagonist’s core. Jef Costello, with his stoic demeanor and unwavering adherence to a personal code, uniquely embodies the spirit of the French New Wave’s fascination with anti-heroes and nonconformists, challenging societal conventions and embracing a lifestyle of isolation and introspection.

11. La Chinoise (1967)

Godard’s fourteenth feature since his breathless debut 7 years back, coming out the year before the (in)famous May ’68 protests, “La Chinoise” throws viewers headfirst into the heart of the Parisian student revolution of the late 1960s. Loosely adapted from Dostoevsky’s 1872 novel “Demons,” this audacious and self-aware film, a pillar of the French New Wave, delivers a whirlwind satire that skewers political ideologies, critiques bourgeois complacency, and playfully deconstructs the filmmaking process itself. Within a cramped Parisian apartment, we find a group of young radical Maoist students led by the fiery and intellectually insatiable Véronique (Anne Wiazemsky). Their days are filled with passionate fervent debates about Marxist theory and Chairman Mao’s teachings, a heady mix of political fervor and adolescent idealism.

The usual Godard hallmarks – jump cuts, jarring edits, handheld camerawork – are marshaled here to create a sense of frenetic energy in sync with the students’ revolutionary spirit. The cramped apartment often feels like a stage set, with the characters constantly entering and exiting the frame, mirroring the theatrical nature of their lives. Characters stare directly into the camera, engage in meta-discussions about filming techniques, and the action is even paused to dissect the film’s message.

Godard cleverly satirizes the students’ dogmatic adherence to Maoist ideology, highlighting the inconsistencies and absurdities within their revolutionary fervor. Their commitment to the cause, seemingly more performative than truly revolutionary, is often overshadowed by petty squabbles and romantic entanglements. Incorporating Brechtian distanciation devices and conspicuous citations of revolutionary texts, “La Chinoise” is a tour de force of formal experimentation: a work that demands active engagement from its audience and refuses to adhere to the comforts of established cinematic norms.

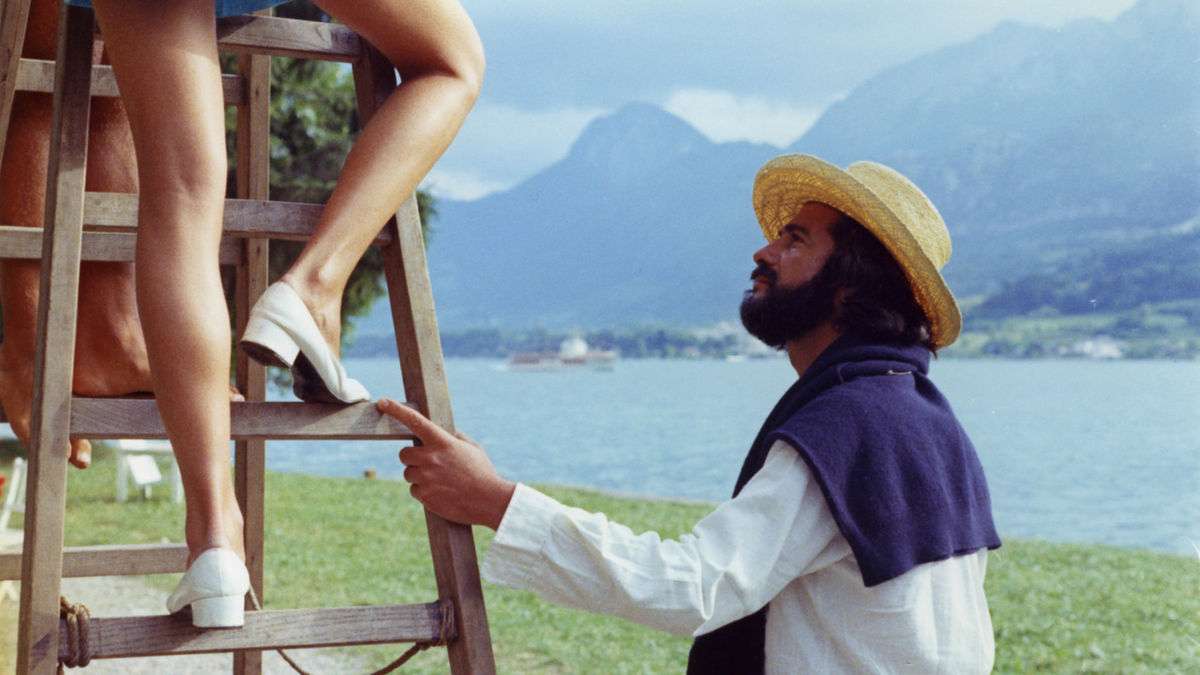

12. Claire’s Knee (1970)

Rohmer’s 1970 film is a deceptively simple portrait of a summer spent navigating the fine complexities of teenage desire and troubling emotions felt yet unspoken. Set against the sun-drenched backdrop of a lakeside village in France, Lake Annecy, it follows Jerome (Jean-Claude Brialy), a divorced man in his mid-thirties, who finds himself irresistibly drawn to the eponymous Claire (Laurence de Monaghan), the captivating teenage daughter of a family friend. As Jérôme navigates the idyllic lakeside setting, surrounded by a cast of eccentric characters and immersed in a world of intellectual discourse, Rohmer’s camera assumes an intimate yet discreet gaze, inviting the viewer to bear witness to the subtle shifts in Jérôme’s psyche and the delicate dance of attraction that unfolds before them.

Unlike many of his New Wave contemporaries who embraced bold formal experimentation and overt provocation, Rohmer’s style is one of quiet observation and profound subtlety. Long philosophical discussions, while seemingly mundane, reveal the characters’ inner lives and their attempts to navigate the difficulties of reconciling their desires. Jérôme’s fascination with Claire’s developing body is a constant undercurrent in the narrative, and the film is suffused with a palpable sense of sexual tension. The camera lingers on Claire’s bare legs, a recurring motif that fuels his unspoken desires and highlights the awkwardness of first love. Jérôme’s fleeting touch of Claire’s knee, the film’s namesake, becomes a potent symbol of his unrequited desire and the transient nature of summer flings.

13. Out 1 (1971)

A truly labyrinthine cinematic odyssey that pushes the boundaries of narrative form and audience engagement, Jacques Rivette’s “Out 1” is one audaciously experimental film of political intrigue, literary mysteries, and swirling conspiracy theories, all delivered with a playful yet provocative spirit. Clocking in at a colossal 13 hours, this sprawling narrative is a series of interconnected storylines revolving around two parallel theatric troupes, their members, and the enigmatic figure of Frédérique (Julie Berto) – a cipher whose mere presence seems to catalyze a series of mysterious events and conspiracies. As the film’s vast ensemble cast navigates the often surreal terrain of Rivette’s creation, the viewer is plunged into a world where reality and fiction blur, where the lines between performance and lived experience become increasingly indistinct.

In one narrative thread, we follow a group of theater actors who are rehearsing a production of Aeschylus’s play “Prometheus Bound” in Paris. The actors engage in a series of improvisational exercises and philosophical discussions, grappling with the nature of performance and the role of art in society. In the other narrative thread, we follow a disparate group of individuals who become embroiled in a mysterious conspiracy involving a secret society known as “The Thirteen” and a series of cryptic messages left around Paris.

Like a vast, cinematic ocean, “Out 1” invites the viewer to immerse themselves in its depths, to surrender to the ebb and flow of Rivette’s audacious vision, and to emerge transformed by the experience. In this sense, “Out 1” may be said to stand as the ultimate embodiment of the French New Wave’s revolutionary spirit, a work that challenges every preconceived notion of what cinema can and should be.

14. The Mother and the Whore (1973)

Jean Eustache’s magnum opus “La Maman et la Putain” was a transgressive late-entry to the French New Wave that sparked equal parts praise and condemnation for what was perceived to be its immoral and obscene content. The plot unfolds against the backdrop of the bohemian milieu of 1970s Paris, where the characters drift aimlessly through their days, engaging in passionate debates about literature, politics, and philosophy while grappling with their desires and insecurities. It centers around Alexandre (Jean-Pierre Léaud), a young intellectual journalist and self-proclaimed revolutionary consumed by a passionate yet volatile relationship with his girlfriend, Marie (Bernadette Lafont). Their bond is constantly tested by Alexandre’s obsessive desire for a third person, a young woman named Veronika (Françoise Lebrun). Alexandre’s possessiveness and lack of emotional maturity create constant friction, pushing both Marie and Veronika to their emotional limits.

Eustache’s film belongs and also stands apart from the earlier works of the French New Wave, a movement that embraced experimentation, with “The Mother and the Whore” taking it a step further. The film’s mammoth runtime, nearing four hours, allows for a deeper dive into the characters’ inner lives and the nuances of their relationships. Its portrayal of female sexuality is another point of divergence from the male-centric gaze often associated with earlier New Wave films. Both Marie and Veronika are strong, independent women who challenge Alexandre’s objectification of them. They are not simply passive objects of desire; they are active participants in shaping the dynamics of their relationship(s). Eustache’s use of long takes, naturalistic dialogue, and improvisational performances creates a sense of spontaneity and realism that is rare in conventional cinema, inviting viewers to immerse themselves in the lives of the characters and experience their psychological journey firsthand.

15. Celine and Julie Go Boating (1974)

In Rivette’s mischievous meta masterpiece, Celine (Juliet Berto), a stage magician with a flair for the dramatic leading a bohemian life, stumbles upon the shy librarian Julie (Dominique Labourier) in a park. Their chance encounter sparks an instant connection, and with a touch of serendipity, Celine ends up sharing Julie’s apartment. Their days are filled with playful banter, philosophical ramblings, and a shared fascination over a box of hard candies – each bite triggering vivid memories and sparking emotional revelations à la Proust’s madeleines. Julie, captivated by Celine’s energy and these glimpses into her life, becomes increasingly drawn to her new friend, to the point where their identities start to blur into one another. As their bond deepens, a shared fascination with a strange, isolated mansion on 7 bis, rue du Nadir-aux-Pommes, takes hold.

Through brief glimpses into the windows and snatches of overheard conversations, the characters become entangled in a seemingly repetitive melodrama unfolding within its walls. A widower, two jealous sisters, and a sickly child appear to be trapped in a cycle of emotional turmoil, a cycle through time into which Celine and Julie are also thrown as they enter the mansion. True to the New Wave spirit, this uncharacteristic narrative is presented in a non-linear fashion, jumping between past and present. Rivette’s editing is playful and fragmented, mirroring the characters’ fluid conversation and their shared preoccupation with the intricacies of storytelling. While the recurring image of the hard candies acts as a portal to the past, unlocking memories and triggering emotional responses, the bustling Parisian streets and the stark contrast with the isolated mansion create a sense of duality – reflecting the film’s exploration of the sheer interchangeability between reality and fantasy.

![One Fine Morning [2022] Review – Mia Hansen-Løve’s intimate drama features a luminous Léa Seydoux but feels overly familiar](https://www.highonfilms.com/wp-content/uploads/2022/12/ONE-FINE-MORNING-2022-MOVIE-REVIEW-768x415.jpg)