Mythical Origins of the Visconti Coat of Arms

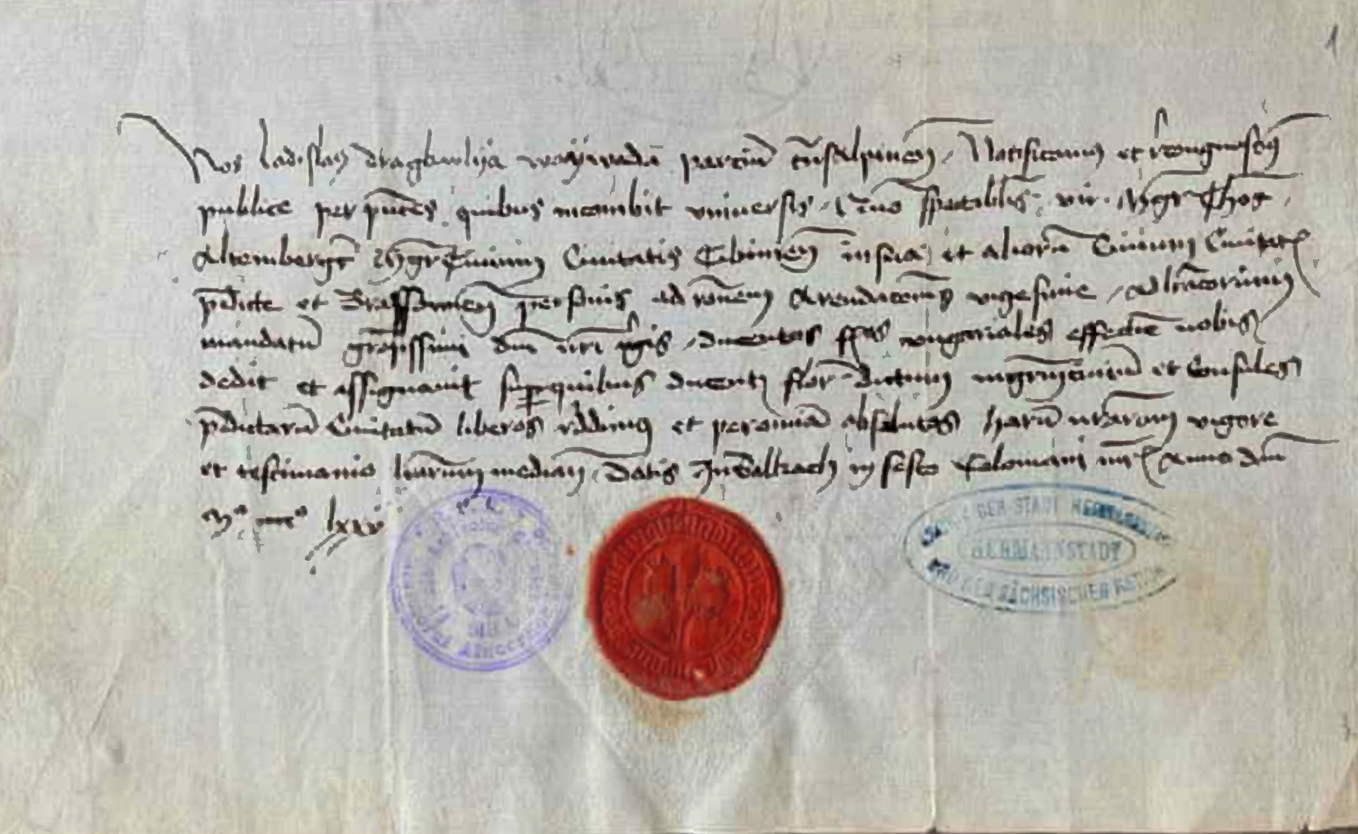

Near year 1000, in Northern Italy the vice-comes (viscount) was an official often in charge of military command. In Milan, around the year 1100, the title became hereditary and a single family assumed the surname Vicecomites (Italian: Visconti). In 1277 the bishop Ottone Visconti, leader of the ghibelline party, defeated the guelphs lead by the Torriani family and the Visconti became Lords of the city. The family ruled in Milan until the death of Filippo Maria (1447), whose daughter Bianca Maria had married Francesco Sforza; their descendants ruled until 1535.

The heraldic device of the Visconti-Sforza family is known as the “biscione” (large snake); it represents a blue snake with a red person in its mouth. Its origins are unknown. A research published by Regione Lombardia (“L’araldica della regione Lombardia”, 2007) points out two major problems:

- It is not known if the Visconti family is from Milan or further North in Lombardy.

- The device could have originated either as an emblem of the city of Milan (later transferred to the Visconti) or directly as a device of the family.

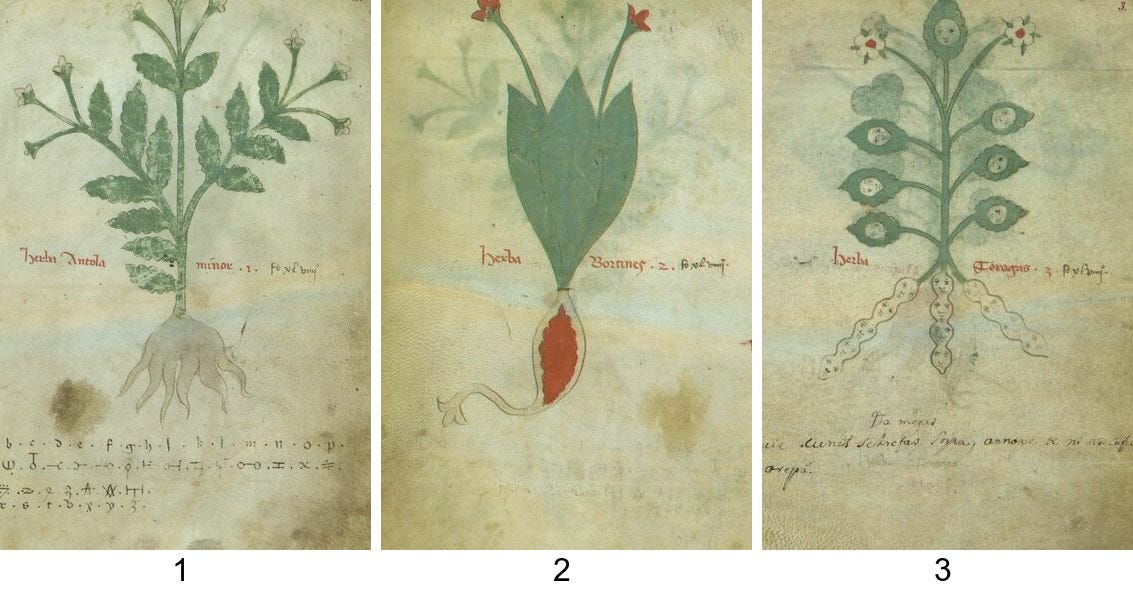

Among the several hypothesis that have been put forward, Emilio Galli (“Sulle origini araldiche della biscia viscontea”, 1919) proposed that the device originally belonged to the city of Milan and that it was inspired by a bronze snake that can still be seen in the St. Ambrose church. The sculpture was possibly brought from Constantinople to Milan around the year 1000.

Michel Pastoureau (“Une histoire symbolique du Moyen Âge occidental”, 2004) suggested that the Visconti were originally the lords of Angera, on Lake Maggiore. The “biscione” could then be a canting device, since the name Angera can be interpreted as “the place of the snakes” (“anguis” is Latin for “snake”).

The following are a few mythical stories from ancient works discussing the origins of the biscione. This collection is certainly not exhaustive.

Bonvesin de la Riva, “De magnalibus urbis Mediolani” (About the great things of the city of Milan), 1288

[Note that the Ottone Visconti mentioned here is not the historical Ottone, who lived more than a century after the first crusade]

“Offeretur quoque ab ipso [communi] alicui de nobilissimo Vicecomitum genere, qui dignior videatur, vexillum quoddam cum vipera indico figurata collore quendam Sarracenum rubeum transgluciente; quod quidem vexillum prefertur; nec alicubi unquam castrametatur noster exercitus, nisi prius visa fuerit vipera super arborem aliquam locata consistere. Hanc autem dignitatem propter excelentem cuiusdam Ottonis Vicecomitis, viri strenuissime indolis, probitatem et victoriam, quam contra Saracenos ultra mare in bello exercuit, dicitur [illis de sua] nobilissima parentella [concessum].

Translation: The same [city] offered to the most worthy of the very noble Visconti family a device with a blue viper swallowing a red Saracen; this device is brought in front [of the army] and they never make camp anywhere, unless the viper is first seen placed upon a tree. Those of this very noble family say that the device was given to Ottone Visconti, a man of great valour, for his probity and success in fighting against the Saracens across the sea.

Galvano Fiamma, “Chronicon extravagans de antiquitatibus mediolani” (An ample chronicle of Milanese antiquity), first half of the 14th Century.

[Bonvesin’s story is expanded with addition of a duel with a Saracen king]

“Antiquitus nostri cives totum suum studium in armis posuerunt. Primum quod apparere consuevit in exercitu est vexillum vipere; istud vexillum prefertur exercitui, nec licet alicui figere castra, nisi prius vipera fuerit in aliqua alta arbore collocata. Hoc privilegium est Vicecomitum, quorum est illud vexillum, quod datum fuit Ottoni Vicecomiti, qui super portam civitatis Ierusalem singulari duello de capite cuiusdam regis saracinorum optinuit. Depingitur enim collore azurrii anullosa circulis terribilibus occulis quendam rubeum sarracenum devorans.”

Translation: Our ancient citizens put all their efforts in making war. What first appears of the army is the banner with the viper; this banner is brought in front of the army and nobody is allowed to make camp if the viper is not first placed above a high tree. This is a privilege of the Visconti, who own this device; it was first given to Ottone Visconti, who took it from the head of a Saracen king after a duel in front of the doors of Jerusalem. Indeed it is painted of a blue colour, with rings and terrifying eyes, as it devours a red Saracen.

Francesco Petrarca, “Rerum Memorandarum Libri” (Books about Memorable Things), 1343–45

[Petrarch adds a completely different story which dates the origin of the emblem to the battle of Altopascio (1325), where the ghibellines from Lucca and Milan defeated the guelphs from Florence and Siena. Such a late date is of course incompatible with other evidence (e.g. Bonvesin).]

Et quoniam prima pars tractatus huius erat de ominibus, attingam quod dum Bononie adolescens in studiis versarer audiebam. Azzo Vicecomes, qui post dominium Mediolani obtinuit, iuvenis satis nempe victoriosus, antequam podagris vinceretur, iussu patris profectus cum exercitu Apenninum transiit; et victis nobis apud Altipassum, duce quidem hostium Castrucio, sed egregia opera eius adiuto, ad vincendum Bononienses pari impetu fortunaque se convertit. In ea expeditione dum forte equo descendens requiescit, ingens vipera nullo comitum advertente in galeam iuxta positam irrupit. Quam cum mox capiti reponeret, sinuoso quidem et horribili sed prorsus innocuo lapsu per decoras interriti ducis genas illa descendit. Eam a nemine ledi passus animosus adolescens ad omen gemine victorie traxit, hinc precipue quod ipse pro signo bellico vipera uteretur.

Translation: Since the first part of this book was about omens, I will add what I heard when I was a boy and studied in Bologna. Azzone Visconti, who later was lord of Milan, was a young man almost always victorious, until he was won by gout. By order of his father, he left with the army and crossed the Apennine mountains. Under the command of one Castruccio [Castracani], but with the help of Azzo’s excellence, [the Milanese] defeated our [i.e. the Florentine] army near Altopascio. [Azzone] then devoted himself, with the same commitment and fortune, to the defeat of the Bolognese. During that campaign, he dismounted his horse to rest and a large viper entered the helmet that was lying next to him; this was not noticed by any of his companions. When he hastily put his helmet on his head, the snake went down the noble cheeks of the fearless duke with a sinuous and horrible, but unharmful, jump. The bold young man ordered that nobody hurt the viper and he interpreted this episode as an omen of a second victory; from here he took the viper as his war emblem.

Andrea Alciati, “Emblematum Liber” (A Book of Emblems), 1531

[Alciati / Alciato was a Milanese jurist who started the very successful tradition of emblem books. The first emblem in his book is a dedication to the duke of Milan. Here the snake is associated with a Hellenistic myth about Alexander the Great: he was said to be the son of Jupiter-Ammon who, under the aspect of a snake, impregnated his mother Olympias. In this way, Alciati suggests a parallel between the greatness of the Dukes of Milan and that of Alexander.]

Insigna Ducatus Mediolanensis

Exiliens infans sinuosi e faucibus anguis,

Est gentilitiis nobile stemma tuis.

Talia Pellaeum gessisse nomismata regem

Vidimus, hisque suum concelebrasse genus:

Dum se Ammone satum, matrem anguis imagine lusam,

Divini et sobolem seminis esse docet.

Ore exit. Tradunt sic quosdam enitier angues.

An quia sic Pallas de capite orta Iovis?

Translation from https://www.mun.ca/alciato/f001.html (Memorial University of Newfoundland)

The arms of the Duke of Milan

An infant springing from the jaws of a curling snake

is your family’s noble device.

We saw the Pellaean king [Alexander the Great] had made such coins,

and had celebrated with them his own descent.

It teaches that while he was sown from the seed of Ammon, his mother was fooled by the image of a snake

and that he was the offspring of divine seed.

He comes forth from the mouth. Is it because in this way, some claim, certain snakes bear their young,

or because Pallas sprang that way from the head of Jupiter?

Paolo Giovio, “Vitae duodecim Vicecomitum Mediolani Principum” (Lives of the Twelve Visconti Princes of Milan), 1549

[Here Alciati’s poetical mention of Alexander the Great is incorporated in an expanded version of Ottone’s story.]

Fuit hic [Galvanius] (ut annales ferunt) Othonis nepos, eius qui ab insigni pietate magnitudineque animi, canente illo pernobili classico excitus, ad sacrum bellum in Syriam contendit, communicatis scilicet consiliis atque opibus cum Guliermo Montifferrati regulo, qui a proceritate corporis “Longa Spatha” vocabatur. Voluntariorum enim equitum ac peditum delectae nobilitatis viginti milia ad Boemundum a Brundusio transitantem adduxere, ne Itali vel studio religionis, vel bellica laude, Gallis inferiores esse viderentur. Caeterum Otho iam duobus asperrimis ad Nicaeam atque Orontem praeliis spectatae virtutis famam consequutus, oppugnante demum Hierosolymas Gothifredo, gloriosa totius exercitus acclamatione, coronam promeruit, quum Volucem Saracenorum ducem medio in campo ad singulare certamen, fortissimum quenque ex Christiana acie provocantem, ipse unus ante alios, nihil eius immanis barbari ferocia, vel terribili insignium armorum specie permotus, fortiter atque feliciter devicit, retulitque de confossi hostis galea opimum plenumque immortali gloria spolium, auritam scilicet viperam inexplicatis spiris minaciter a cono cassidis erectam, et puerum passis manibus devorantem: quod unum auspicatae virtutis argumentum, non modo gentilitiae laudis gestamen fuit, sed et posteris id insigne audacter usurpantibus, et imperia, et opes, et late gloriam protendit. Fuere qui existiment Volucem ex stirpe Alexandri Magni progenitum, tulisse pro insigni viperam, ex Olypiadis fabula, puerum parturientem, quod ea a dracone se compressam fuisse, Iovis imaginem praedicaret.

Translation: The chronicles say that [Galvanius] was the nephew of Ottone who, following with great piety and outstanding courage the call of a very noble war trumpet, fought in the crusade in Syria. He shared decisions and actions with the prince William of Montferrat who, for his height, was called “Longsword”. They brought twenty thousand volunteers, knights and infantry of chosen nobility, to Bohemond [of Taranto] when he passed from Brindisi, so that the Italians did not appear to be lesser than the Gaul for either religious zeal or praise in war. He obtained fame of great valour in two terrible fights in Nicea and on the Orontes. During the siege of Jerusalem led by Godfrey [of Bouillon], [Ottone] deserved the wreath by acclamation of the whole army: in the middle of the field, he faced in single combat Voluce, leader of the Saracens, who had been insistently challenging the Christian camp. Among all the others, only he was not scared of the great ferocity of the barbarian, nor of the frightful emblems on his armour. He won completely and happily and he took from the helmet of the dead enemy a trophy of immortal glory: a eared viper with ringed spires threatening from the top of the helmet in the act of devouring a child up to his arms. That emblem was an omen of future virtue, not only of the pride of the family, but it also extended to his descendants boldly taking power and to their rule, deeds and great glory. Some believe that Voluce descended from the lineage of Alexander the Great: he took as his device a viper giving birth to a child because of the fable about Olympias coupling with Jupiter in the shape of a dragon.

Carlo Torre, “Ritratto di Milano” (A portrait of Milan), 1714

[A passage from a much later source that presents three different legends in a sceptical tone. The last story was modelled on Petrarch’s, taking it back in time from the 14th to the 8th Century.]

Sentiste poc’anzi a dirvi essere questa chiesa [San Sepolcro] la vera effigie di quel Tempio che eretto stassi in Palestina, per tale io la assicuro. Furono dal Cavaliere [Rozinus] di Cortesella a minuto portate da quelle parti a Milano le misure giuste, e sulle stesse volle egli osservare innalzate le sue fattezze; haverete altre volte inteso ancora come in quella battaglia seguì fiero duello tra Otto Visconte ed un saraceno chiamato Voluce, il quale vinto dal milanese eroe videsi astretto con la perdita della vita a lasciarsi levar d’addosso gli militari corredamenti, quindi acquistata havendo il Visconte la celata, in cui veggavasi scolpita una vipera divoratrice d’umano aspetto, determinò d’ergere tal figura nell’insegna di sua casa, la cui prodezza leggesi rammemorata dal prencipe dell’eroica poesia italiana, dicendo nel Canto Primo della Gerusalemme [Liberata]:

E’l forte Otton, che conquistò lo scudo,

In cui da l’angue esce il fanciull’ignudo.

Ma ditemi, che ve ne prego, per qual cagione a tal racconto voi tutti havetemi in faccia immobiliti i vostri lumi? Forse parvi ch’io habbiavi detto menzogna? Non lo vi pensate, parlano in tal guisa molti istorici di non poca autorità. Settemila furono i milanesi soldati che trovaronsi alla conquista del Sacro Avello, essendovene capitan generale quest’Otto Visconte sì generoso, come già dissivi, e ritornatosene glorioso alla nativa città, dopo varie feste in allegrezza di così insigne vittoria, essendosi anche accettata per pubblica insegna della stessa città l’effigie dell’ottenuta vipera, fugli consegnato il governo civile, e poscia accasatosi con Lucrezia di sangue regio francese, restò per sua cagione fiorita in più secoli di prencipi de’ Visconti la pianta.

Io m’immagino c’habbiate sentito altri racconti intorno all’insegna della viscontea vipera, e che non troppo autentica vi dimori nel credito l’acquistato arnese del saraceno Voluce: attendetemi, che narrerovvi ciò che tiensi da altri scrittori in questo particolare.

Da mostruoso drago sofferiva Milano incontri fieri, successa di poco la morte di Sant’Ambrogio: questi annidavasi dove ora s’innalza il tempio di San Dionigi in profonda caverna, ch’essendo quel sito lungi dalle cittadine mura rimaneva disabitato, e da commerci assai lontano, gli danneggiamenti erano orribili, le morti copiose, e le temenze spaventevoli. Non sorgeva giorno che qualche persona non lo segnasse col proprio sangue, che prima dell’occaso del sole non cadesse nella voragine di sua gola, della di lui fierezza ne discorreva ogn’uno, ma ad abbassar suo orgoglio riusciva tenue ogni ardire, alla tema si sospendevano gl’impieghi Civili, anzi, racchiusi nelle proprie abitazioni, gli stessi cittadini sapevano solo contribuire alla speranza quasi disperata stentati spiriti. In tante angoscie, che il cielo alla fine non priva mai alcuna patria o di valorosi cavalieri o di generosi Curzii, ad esporre ai perigli la propria salvezza per arrecarle soccorso; un tal’Uberto Visconte, uso agli usberghi per essere seguace di Marte, vantossi di dargli la morte. Accintosi dunque all’impresa, non uscì dal campo se non cinto di lauro, quando altri attendevanlo vestito di languori. Troncato il teschio al mostro a perpetua raccordanza lo desiderò per impresa del suo casato, e vogliono molti che da questo eroe la biscia de’ Visconti sia nata.

Ecci anche un altro racconto, per non passarvi nulla sotto silenzio, che non ha dell’improprio. Desiderio, ultimo re de’ Longobardi, germe de’ conti d’Angera, che tanto vuol dire Visconti, dormiva un dopo pranzo all’uso de’ soldati sull’erba, stanco per intraprese faccende belliche, e parendo a’ cortigiani suoi che troppo si smenticasse nel sonno, giacché la guerra non vuol per amici intrinseci gli agi, volgendosi a lui per risvegliarlo, fu scoperto haver d’attorno alla fronte, che gli faceva corona, una vipera, ambiziosa forse di farsi vedere una volta cerchio regio di un eroe, a dispetto della sua sorte che constringevala ad essere sempre nodo di ruvide zolle. Distoltosi dal sonno illeso da’ suoi morsi, e stimando prodigiosa l’azione, dicesi che anch’egli volle tanto eccesso eternare esponendo a pubblici sguardi nella sua insegna l’effigie di tal serpe. Sonovi altri successi ancora, ma gli tralascio tacendo, per non dimostrarmivi troppo prolisso in narrazioni. Da una di queste istorie è divenuta la viperina insegna de’ Visconti, poco importandomi che ne sia l’autore od Uberto, o Desiderio, od il guerriere che in Palestina vinse il saraceno Voluce.

Translation: I said that this church [San Sepolcro] is the true effigy of that Temple which is found in Palestine, of this I assure you. The right measurements were brought from those parts to Milan by the Knight [Rozinus] of Cortesella, and he wanted to build a replica; you may have heard on other occasions how in that battle a fierce duel ensued between Ottone Visconti and a Saracen called Voluce, who, defeated by the Milanese hero, lost his life and was stripped of his military gear. Ottone, having obtained the helmet, in which a viper devouring a man was carved, decided to use this figure in the insignia of his house, whose prowess can be read mentioned by the prince of heroic Italian poetry, saying in the First Canto of Jerusalem [“Jerusalem Delivered”, 16th Century poem by Torquato Tasso]:

It is strong Ottone who conquered the shield

In which the naked child emerges from the snake.

But tell me, please, why do you all fix your eyes on my face at this story? Perhaps it seems to you that I told you a lie? Don’t think so, many historians of no small authority speak in this way. Seven thousand Milanese soldiers took part in the conquest of the Holy Sepulchre, this Ottone Visconti being their generous captain general, as I told you. When he returned to his native city in glory, after various celebrations in rejoicing at such an illustrious victory, the effigy of the viper was also accepted as a public sign of the same city, and government was handed over to him. [Ottone] married Lucrezia, of French royal blood, and the plant of the Visconti princes flourished for several centuries.

I imagine that you heard other stories about the Visconti’s device of the viper, and that the helmet of the Saracen Voluce does not seem too authentic to you: I will tell you what other writers say on this subject.

Milan suffered violent attacks from a monstrous dragon, shortly after the death of Sant’Ambrogio: it nestled in a deep cave where the temple of San Dionigi now stands; since that site was far from the city walls, it remained uninhabited and very far from commerce. Damage was horrific, deaths copious and there was much fear. Not a day rose that some people did not mark it with their own blood, that before sunset someone did not fall into the abyss of the dragon’s throat. Everyone talked about its pride, but nobody dared to face it; because of its fear, they suspended civil affairs, indeed, enclosed in their own homes, the citizens themselves could only contribute their halting sighs to an almost desperate hope. In such distressful times, in the end heaven never deprives any homeland of valiant knights or a generous [Marcus] Curtius, to bring assistance and salvation from dangers; a certain Uberto Visconti, accustomed to arms for being a follower of Mars, had the honour of killing the dragon. So set about the enterprise, he did not leave the field until girded with laurel, when others expected him dressed in suffering. Cutting the monster’s head, in perpetual memory, he chose it as the emblem of his family. Many think that the Visconti snake was born from this hero.

There is also another story which deserves to be mentioned, in order not to omit anything. Desiderius, the last king of the Lombards, offspring of the counts of Angera, which means so much as the Visconti, slept one after lunch on the grass as usual with soldiers, tired from undertaking warlike matters. It seemed to his courtiers that he slept too much, since war does not want comfort for its intrinsic friends; when they turned to him to awaken him, he was discovered to have around his forehead a viper, which was like a crown; maybe the snake wanted to once show itself as a hero’s royal circlet, in spite of its fate that forced it to always be a knot among rough clods. Awakening from sleep unharmed by its bite, Desiderius deemed the fact prodigious. It is said that he too wanted to eternalize such great feat by showing the effigy of this snake to public gazes on his banner. There are still other stories, but I omit them in silence, so as not to appear too long-winded in narratives. The viper coat of arms of the Visconti comes from one of these stories, it matters little to me whether its author is Uberto, or Desiderius, or the warrior who defeated the Saracen Voluce in Palestine.