Worth, the new movie from director Sara Colangelo and screenwriter Max Borenstein, tells the story of Kenneth Feinberg, the man who was put in charge of the September 11th Victim Compensation Fund. The fund, set up only days after the attacks, was Congress’s attempt to simultaneously protect airlines from ruinous lawsuits and compensate the families of the victims for their unfathomable losses. We’ve consulted Feinberg’s book, profiles of some of its main characters, and other sources to sort out what’s true and what’s artistic license in the Netflix drama.

Kenneth Feinberg

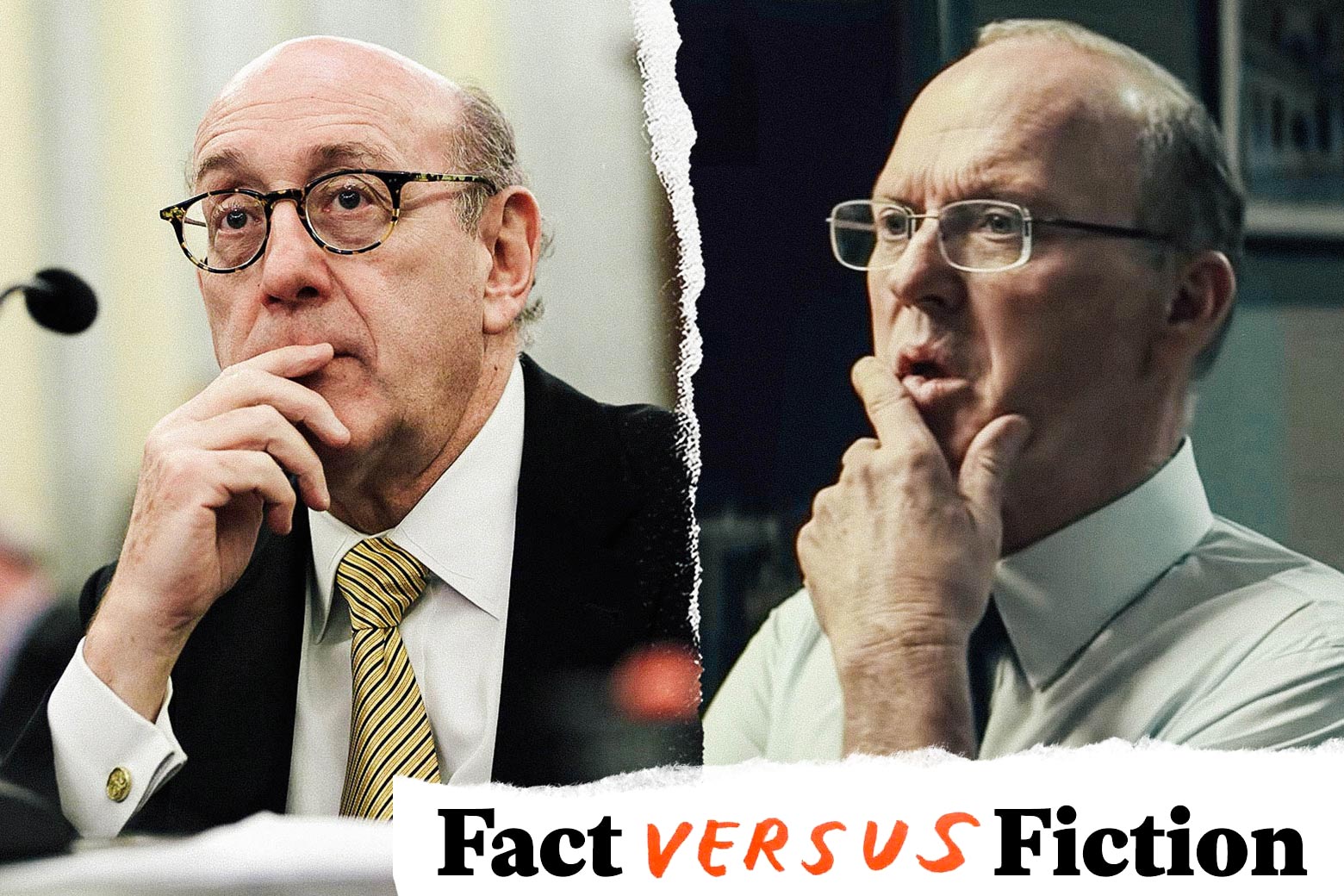

Kenneth Feinberg, the lawyer who was Special Master of the September 11th Victim Compensation Fund, is played by Michael Keaton in the movie, and his portrait is typical for this kind of movie: There are a lot of correct details, but the overall shape of events has been massaged a little to fit into a film narrative. Feinberg chronicled his experiences overseeing the fund in What Is Life Worth?: The Unprecedented Effort to Compensate the Victims of 9/11, and it’s one of the primary sources for Borenstein’s screenplay. As seen in the movie, Feinberg is immediately identifiable as being from Massachusetts, but his accent is a little less strong than Keaton’s (extremely fun) performance. By way of comparison, CSPAN has video of the Dec. 20, 2001 press conference at which he explained the victim compensation fund:

Feinberg’s love of classical music is real, as is the listening room in his house, complete with an extensive and well-catalogued CD collection. The bravura sequence in which Feinberg, ensconced in his headphones, fails to notice his fellow passengers receiving news of the Sept. 11 attacks, however, is an invention of the movie. On the morning of Sept. 11, the real Feinberg learned about the attack in stages: He saw the aftermath of the first plane hitting the World Trade Center on a TV in a common area at the University of Pennsylvania after teaching a class there, and then, on a train from Philadelphia to Wilmington, passengers with portable radios spread the news of the second tower and the attack on the Pentagon. He wasn’t anywhere near the Pentagon and did not see the aftermath from a train window.

The movie also fudges some details about Feinberg’s involvement in the Sept. 11 Victims Compensation Fund, implying that Sen. Ted Kennedy asked Feinberg to help out because so few people specialized in victim compensation. Feinberg did have extensive experience in that sort of case, having worked on the Agent Orange settlements as well as other high-profile mediations, but he lobbied to get the position. The movie shows him in a meeting with senators Ted Kennedy and Chuck Hagel on Sept. 22, 2001, discussing how the victims fund should work. Although it’s an effective way to deliver a lot of exposition, that meeting probably didn’t happen. Sept. 22 was the day George W. Bush signed the bill establishing the fund, and by then the details had already been hammered down. According to Feinberg, he got the job by calling Hagel, who’d been in the the United States Department of Veterans Affairs during Feinberg’s work on the Agent Orange cases, after reading about the bill in the newspaper. Hagel advanced Feinberg’s name to Attorney General John Ashcroft, who appointed Feinberg after meeting with him twice.

Worth is a movie about a lawyer finding his conscience, and to fit that mold, Feinberg is made to seem more aloof than he really seems to have been. In his memoir, he explains that he spent about a year traveling to meet with the families of the victims of Sept. 11, presenting the details of the compensation fund. The movie compresses several anecdotes from Feinberg’s memoir from these early meetings into one disastrous scene in which he utterly fails to connect with the audience. That’s standard dramatic compression, and profiles of Feinberg from the time confirm that he came across as pretty chilly and was not exactly beloved by the families of the victims. But the movie goes out of its way to play this up, showing Feinberg meeting with the lawyers of high value victims while an associate and his office administrator Camille Biros meet with families from South America in an office overlooking Ground Zero. In fact, Feinberg attended both of those meetings on April 29, 2003.

The movie goes on to suggest that Feinberg was not used to meeting with victims one-on-one until the widow of a fireman showed up late at night when the other lawyers weren’t around. Although Feinberg began reaching out to families through town hall meetings, within three months he began offering one-on-one meetings to any family who wanted one, not because of a change of heart but because he realized they’d need better estimates of their potential award before deciding to file for compensation. There was no moment when Feinberg threw out his formula for determining compensation, delighting his coworkers who secretly knew he’d do the right thing when the chips were down. According to his memoir, his plan from the beginning had been to use his discretion in individual cases to narrow the gap between the highest and lowest compensation. Feinberg does say in his memoir that he became more empathetic and a better listener from the experience of working with the families of the victims, but the corporate-lawyer-regains-his-humanity arc is pure Hollywood.

Charles Wolf (Stanley Tucci)

Charles Wolf, the husband of a Sept. 11 victim who was an early critic of Feinberg’s administration of the fund, is played by Stanley Tucci in the movie. He’s a much bigger part of Feinberg’s story in the movie than he seems to have been in real life, and some adjustments have been made to make him a better foil for Feinberg. For starters, he’s moved up a few income brackets: We see him saying goodbye to his wife Katherine on the morning of Sept. 11 in a spacious apartment with a dining room, kitchen, and hardwood floors. The actual Wolf, according to an excellent Buffalo News profile, shared a studio apartment with his wife, featuring “old, gray carpet” they had planned to replace, something he still hadn’t gotten around to in 2015. This isn’t just a glow-up: the movie needs Wolf to be Feinberg’s peer, and it’s the first of several changes made to achieve that effect. In real life, Wolf was a former Kodak sales representative who had quit in the 1990s to become an Amway salesman. His wife was an executive assistant at Marsh & McLennan, a professional services firm with offices in the World Trade Center. The movie changes this to a fictional law firm, Kyle and MacAllen, and although it never says she’s not an executive assistant, Wolf describes working for them as her “dream job.” This sets up an emotional connection between Wolf and a fictional associate at Feinberg’s firm, whose plans to work at the same law firm were disrupted by the Sept. 11 attacks.

Wolf and his wife were both amateur opera singers, as mentioned in the film, but there’s no evidence he had any kind of fateful meeting with Feinberg at a 9/11 memorial concert. The event, too, is a composite: According to a sign on the door, they are attending “An Evening of Remembrance and Reflection,” a title used for an event at Lincoln Center in 2011. The music they see performed, however, is Lost Objects, which is not about 9/11 and was not staged in New York until 2004. The idea seems to be to evoke the first performance of John Adams’ “On the Transmigration of Souls,” which happened in 2002 (although the scene seems to be Sept. 6, 2003). The point of the scene, though, is not the music, but the pep talk Wolf gives Feinberg, telling him a long story about his futile attempts to save a historic bridge while serving on the city council in Ithaca. None of that seems to have happened: the Wolfs didn’t live in Ithaca, Charles Wolf does not seem to have held office there, and even Wolf’s involvement with the Greenwich Village Society for Historic Preservation seems to be an invention, an easy shorthand to show he’s the kind of guy who writes angry letters.

The part the movie gets right is that Wolf was a harsh critic of Feinberg and his plan for compensation who eventually came around, although he wasn’t necessarily as egalitarian as he appears in the movie. His website, fixthefund.org, is still up and features a copy of his original complaints: Among other things, he was unhappy that high income earners would have their compensation capped, which he blames on Feinberg’s “Democratic ‘income redistribution’ mentality.” He eventually became convinced Feinberg was doing a good job and updated his website, proclaiming “the fund is fixed,” as seen in the movie.

Camille Biros (Amy Ryan)

Camille Biros is played by Amy Ryan on-screen, and if her official role at Feinberg’s firm is not entirely clear in Worth, that’s because the Sept. 11 Victims Compensation Fund seems to have been a turning point for her career. Biros, who is not a lawyer, became Feinberg’s administrative assistant in 1979 when he was working for Ted Kennedy. By 2001, she was Feinberg’s “law firm administrator,” and although she was heavily involved in the Sept. 11 Victims Compensation Fund, as seen in the movie, it was the first time she’d worked on a similar project. A 2017 profile of Biros has her working as an equal partner with Feinberg by the time it was published, but that wouldn’t have been true in 2001. Her role in the film, though, is structural more than anything: She’s there to be Feinberg’s conscience and an audience surrogate, grimacing when he screws up and smiling when he makes the right decision.

Composite Characters

Any movie based on a true story has composite characters, but Worth has more than most, because both Feinberg and the filmmakers are sensitive to the privacy of the families of the Sept. 11 victims. There are two important composite characters who are not victims, though: sleazy corporate lawyer Lee Quinn (Tate Donovan) and up and coming Feinberg associate Priya Khundi (Shunori Ramanathan). Quinn is there to voice the concerns of the families of high-income victims and, not incidentally, give the film a villain. The sequence in which Feinberg’s meeting with Quinn is contrasted with Biros and Khundi’s meeting with South American families maps to two actual meetings—Feinberg attended both—and Quinn appears to be filling in for executives from the investment banking firm Keefe, Bruyette, & Woods. The part of the movie in which Charles Wolf nearly signs on to a lawsuit with an unscrupulous lawyer but decides not to for moral reasons, however, doesn’t seem to have any real-world analogue, nor does the scene where Feinberg nearly signs on with Quinn but then dumps a pen’s worth of ink over the contract and strides out of the restaurant.

As for Priya Khundi, she’s a pure invention who serves an important structural role: She’s the first person from Feinberg’s firm to make a real connection with Charles Wolf, because the filmmakers gave her a backstory that parallels Katherine Wolf’s. Feinberg names the lawyers who made up his core team in his memoir: Besides Biros, they were Deborah Greenspan, Jacqueline Zins, and Jordy Feldman.

The film’s handling of the families of the Sept. 11 victims is a little trickier. Feinberg was scrupulous about getting permission from the families he mentioned by name in his memoir, and whenever he is making “a general point that would not be clarified by reference to a particular family,” he uses composites. The film’s opening monologue is a slightly modified version of testimony quoted in Feinberg’s memoir, and many of the other minor characters are straight from the page, including the widow who needed her award faster than other victims because she had only a short time to arrange things for her children before she died of terminal cancer. (It’s not in the movie, but Feinberg bent the rules to get her the money in time.) Besides Charles Wolf, however, the victim the film spends the most time on is Karen Donato (Laura Benanti), the widow of a firefighter who, Feinberg discovers, has a secret mistress with whom he’s had two additional kids. She’s not in Feinberg’s memoir, and Karen Donato is not her actual name, but she seems to have been real, because Feinberg has told the story elsewhere. In the movie, he eventually tells the widow about the mistress and the other children. In real life, however, it didn’t go that way. Here’s how he told the story in a 2019 lecture at Duke University’s Kenan Institute of Ethics, where he referred to the fireman by the pseudonym “Mr. Malm”:

We went around and around on this for a couple of weeks with the staff, and then one night, at three A.M., I get up, and my wife: “What’re you doing up at 3:00 A.M., what’s the problem?”

“Well, this woman, and there’s Mr. Malm, and there’s two kids, and the mistress, what do you—”

“Don’t you DARE tell her!”

Well, that solved that problem. That was a solution, that was an ethical resolution of that issue. We cut one check to the grieving widow and her three children, and without her knowledge, we did a separate calculation and cut a check to the girlfriend as the guardian of the two children. That was it. Now that was almost 20 years ago—I will bet you anything they know each other, and it’s all now out. I don’t know. Not my place. Not my place.

Well, that solved that problem. That was a solution, that was an ethical resolution of that issue. We cut one check to the grieving widow and her three children, and without her knowledge, we did a separate calculation and cut a check to the girlfriend as the guardian of the two children. That was it. Now that was almost 20 years ago—I will bet you anything they know each other, and it’s all now out. I don’t know. Not my place. Not my place.

It’s an ironclad law of cinema that if you have the opportunity to add a scene in which a magnificent actress gets to find out her dead husband was having an affair, then later explain that she already knew and has come to terms with the knowledge, you should take it, and that’s what happened here. That’s how you know you’re not watching a documentary.