Finding Brian: On the Beach Boys’ ‘Surf’s Up’

Now 50 years old, this fascinating entry in the Beach Boys’ catalog makes space for Brian Wilson’s genius while also seeing the other members step up.

by Ben Greenman

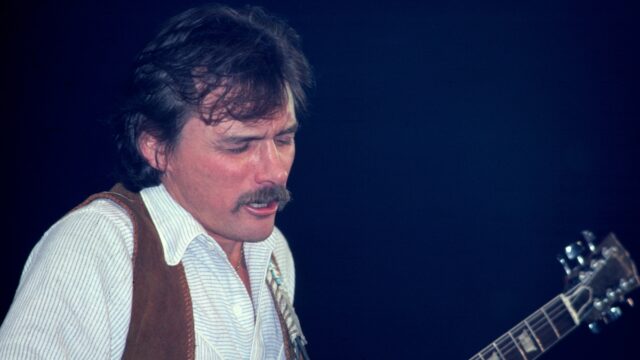

The Beach Boys had conquered the world. They had done it even with what was, by any measure, an unorthodox arrangement. Brian Wilson, the band’s co-founder, principal songwriter and most inventive musical mind, had taken himself, if not out of the picture, then out of part of the picture — namely, out of the part that happened on the road. Since a breakdown on an airplane a few days before Christmas of 1964, Brian had been unwilling (read: unable) to travel with the band. The flights, the road and the screaming crowds, all overwhelming to him, were incompatible with his psychological state. He stayed home and wrote. The rest of the band — Brian’s brothers Carl and Dennis, his cousin Mike Love and his high school friend Al Jardine — toured without him. Glen Campbell filled in.

The arrangement worked wonders, for a while. In the immediate wake of the breakdown and the retrenchment, the band finished The Beach Boys Today!, a peerless album and a major step forward, and then just over a year later released Pet Sounds, an even more peerless album that changed the nature of rock and roll. The public took notice. The Beatles took notice. The band began work on its Brian-driven magnum opus, Smile, and failed to bring it to fruition, after which Brian receded further. Other members of the band stepped forward as composers, as singers, as sites of meaning. Across the second half of the ’60s, the albums that appeared either forged a new identity for the group: more communal, looser, more interested in their soul roots (Wild Honey, 20/20) or found Brian trying to advance his case with mixed results (the first side of Friends).

But after the creatively satisfying Sunflower stalled commercially, it was time for another shift. For starters, Brian wanted to change the name of the band. They had grown up, he said, to the point where he thought they needed to identify themselves in a way that emphasized their maturity. “We’re no longer boys,” he said. His suggestion, the Beach, was summarily rejected. But the group was new in other ways. They had left Capitol for Reprise, which distributed releases on the band’s own imprint, Brother Records. And on the LP after Sunflower, they went back to the drawing board, in a sense, recording and releasing an album with minimal participation from Brian.

Or is that incorrect? Minimal participation isn’t exactly the right way to put it. For Surf’s Up, Brian was less present, certainly, or present in different ways, and the other members stepped forward. In part they stepped forward to bring the group into the present. Mike Love rewrote Leiber and Stoller’s “Riot in Cell Block #9” as a recent history of the free speech movement on campus, culminating in Kent State. Love and Al Jardine wrote “Don’t Go Near the Water,” an environmental anthem. Carl Wilson wrote a pair of songs that demonstrated his increasing sophistication, “Long Promised Road” and “Feel Flows.” Bruce Johnston, who had joined the band after Brian’s departure back in 1965, contributed the nostalgic “Disney Girls (1957).” So where did that leave Brian?

It left him with Jack Rieley, though what that implied isn’t entirely clear. Rieley was a Beach Boys fan who had created a radio documentary about the group at a time when their future seemed uncertain — or, more specifically, when they faced the prospect of losing Brian entirely to retirement or to mental anguish and becoming a kind of self-tribute band. Rieley sought out Brian at the Radiant Radish, the L.A. health food store the musician had co-founded, and was soon brought into the fold as the group’s manager. His ideas for the band extended to wardrobe (he did away with the striped shirts that had become a kind of post-barbershop-quartet cliché, encouraging them to take the stage wearing their street clothes) and booking (he pushed them toward more progressive venues and festivals). He also started collaborating with the band, though what that meant varied. Sometimes it was simply a matter of giving Brian confidence to do what he wanted to do anyway, as on the title track, which Brian had started back in the Smile days with Van Dyke Parks but had never seen clear to finish. Rieley encouraged him to include it and Brian, sheepishly, said that he would have to if Rieley insisted. (This may have also given Brian the courage to include “’Til I Die,” a heartbreakingly masterful song about existential dread that didn’t find favor with the group when he first played it for them.)

The cover painting of Surf’s Up invokes James Earle Fraser’s iconic sculpture “End of the Trail.”

Other times the collaboration extended to coming up with lyrics for music that the Wilsons had written. Both Carl Wilson songs were co-written with Rieley, as was the album’s third — and most distinctive — Brian composition, “A Day in the Life of a Tree.” The song, tucked away in the middle of side two, returned to the environmental concerns of “Don’t Go Near the Water” but from a far stranger place, imagining what a tree might feel in the hostile world of men. Brian and Rieley talked about it, and Rieley went away and wrote lyrics. They were purple and went everywhere. One verse, the first, is sufficient to illustrate:

Feel the wind burn through my skin

The pain, the air is killing me

For years my limbs stretched to the sky

A nest for birds to sit and sing

The song’s excessive (and eccentric) sensitivity seemed like a perfect match for Brian, but he didn’t want to sing the lead vocal. Dennis tried it but couldn’t quite get it. Brian asked Rieley to sit in the control room. Then Brian took a crack at the song, once, twice, three times. He tore off the headphones and stormed out of the booth. “Jack,” he said, “I don’t understand this song anymore.” He was wild-eyed, worried, sliding back toward “’Til I Die” territory. Rieley agreed to sing a guide vocal to explain the lyrics to Brian. When he emerged, Brian was smiling. “Thank you for singing that song,” he said. The wild eyes had been a hustle.

The record was well received. Rolling Stone praised its ecological preoccupations. Other reviewers found it a slight step below Sunflower, though they conceded that it had the gravity to make a greater impression over time. Like many Beach Boys albums, it was the end of an era. The ensuing half-decade of the group’s evolution was tangled and strange, with Surf’s Up succeeded by Carl and the Passions — “So Tough,” a nearly Brian-free record that pulled together odds and ends, including material from a canceled Dennis Wilson solo album. (The album has generally been considered one of the weakest entries in the band’s entire catalog, though Elton John likes it.) And that was succeeded by Holland, a more legitimate sequel to Surf’s Up that was recorded, as the title suggests, in Holland, and relied on Brian’s songwriting only slightly more, in the opening track, the magnificent “Sail On, Sailor.”

At Radio City Music Hall in 2001, there was a Brian Wilson tribute show where the Beach Boys’ songs were performed by other artists: Paul Simon, Billy Joel, the Boys Choir of Harlem, Ricky Martin, Matthew Sweet and more. Elton John did not sing anything from Carl and the Passions — “So Tough,” though he did sing “God Only Knows” and popped up again for a duet with Brian on “Wouldn’t It Be Nice.” Surf’s Up was represented not by “’Til I Die” or “A Day in the Life of a Tree” but by the title song, which was performed by Vince Gill, Jimmy Webb and David Crosby. In his memoir, I Am Brian Wilson, Brian recalls the night.

I was sitting on a stool at the side of the stage and David Crosby came off and said, “Brian, where did you come up with those fucking chords? They’re incredible.” I shook my head. “You know,” I said, “I said goodbye to that song a long time ago.”

The new box set Feel Flows: The Sunflower & Surf’s Up Sessions 1969-1971 features remastered versions of both albums, plus over 100 alternate mixes, unreleased tracks and more.