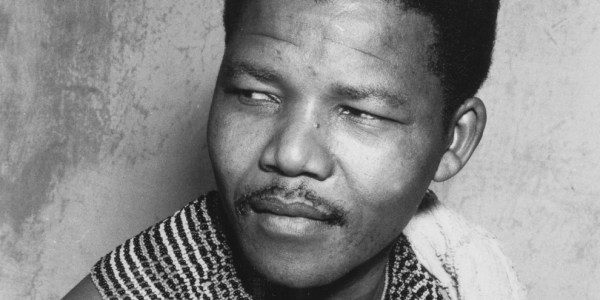

Mandela’s name echoed through the childhood of anyone who grew up in Southern Africa in the '60s and '70s. No one knew what he looked like, what he sounded like or what he would say if you could hear him; there was only silence from Robben Island, a deafening silence.

He was one of the main reasons I chose journalism as a profession. As a white person in the South Africa of those days, you could not just enter a township.

If you did, you’d be almost sure to be picked up by police. There were informers everywhere and they took their jobs seriously. As a journalist you could make your way into a township. The apartheid government did try to keep up the appearance of press freedom of sorts as an entree into democratic societies. And once you were in the townships you realized quickly how polarized the country was, how unequal the lives of South Africans at a time when every aspect of life was segregated. A time when police could knock on your door and inspect your bed sheets, if they suspected you of breaking the laws prohibiting interracial contact. A time of ruthless degradation and poisonous subversion by the security police.

In the townships, the name Mandela was alive, even though no one had an image of the man. Somehow the name kept hope alive, kept a generation that had never set eyes on him facing live bullets, dogs and those vicious hippo hide whips, singing, dancing, throwing stones and petrol bombs at the lumbering yellow armored police vehicles. They bled and died and some never came back from the trauma.

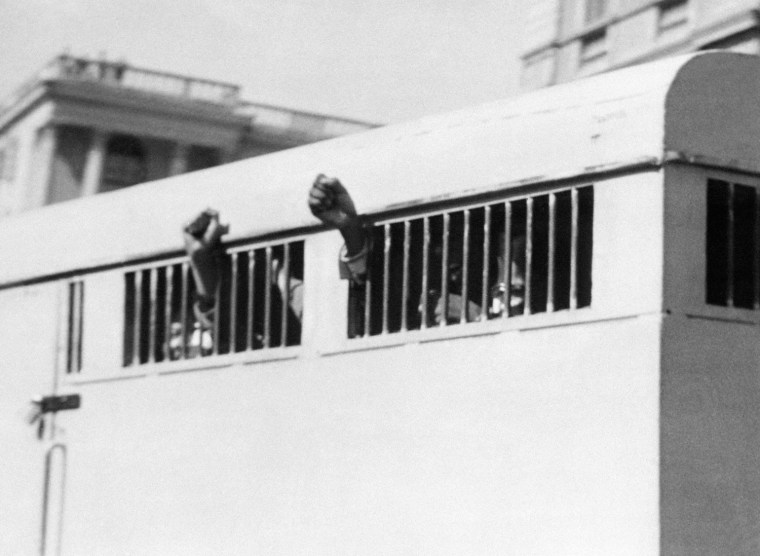

I remember spending days in Soweto’s Vilakazi Street with other journalists, waiting for Winnie Mandela to return from one of her rare trips to Nelson's prison. The road past the little matchbox house with the polished concrete verandah floor was not tarred, like today, and Soweto was swallowed up at night by smog from the coal fires. Winnie would bring back snippets of information; there was a steely sadness in her eyes after these visits. When Mandela finally emerged from behind bars, after 27 years, he had found serenity and a certain mellowness in himself that helped him negotiate a future for his country. Winnie had become much more steely.

I remember the day, after his triumphant walk out of the prison when he came out into Bishop Tutu’s garden with Winnie, wearing that big, genuine smile and that absolute sense of purpose. Everyone who met Mandela came away knowing that there was no front, no window dressing and a genuine respect for the human spirit.

One of the highlights of my journalistic life came in 2007 when we were preparing Matt Lauer’s "Where in the World Trip" to Cape Town. I had spent some time trying to get a taped message from Mandela to Matt for the live show. After a nerve wracking couple of weeks I had a call on the day before the live show and was told to let Madiba know what we were expecting from him – could I write up an idea of what I’d like him to address in 30 seconds. I had a couple of hours of soul searching over what I thought was the crux of his message and how I’d get him to translate his central idea to a US audience. In the end it was all fairly simple, it was about hope, respect and if it can work in a country as polarized as South Africa, it could work anywhere.

He seemed to agree and I was dumbstruck when the taped message came back, almost word for word the "rough guide" I’d sent as a suggestion.

Somehow I always felt the truth can be simpler than we like to think...now I know.