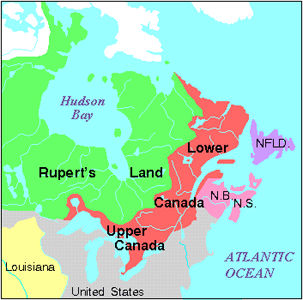

The Constitutional Act, 1791 was an act of the British Parliament. It was also known as the Canada Act. It divided the Province of Quebec into Upper Canada and Lower Canada. The Act was a first step on the long path to Confederation. It also gave women who owned property in Lower Canada the right to vote. But its rigid colonial structures set the stage for the Rebellions of 1837–38.

This article is a plain-language summary of the Constitutional Act, 1791. If you would like to read about this topic in more depth, please see our full-length entry: Constitutional Act, 1791.

Response to Loyalist Immigration

The Constitutional Act received royal assent in June 1791. It came into effect on 26 December. It was part of the reorganization of British North America. This took place as thousands of Loyalists were seeking refuge after the American Revolution. ( See also Loyalists in Canada [Plain-Language Summary].)

A bill was prepared by William Wyndham Grenville. It was modelled on a law that had created the colonies of New Brunswick and Cape Breton in 1784. Grenville’s bill made sure that British-style government would continue to develop in the region covered by the Quebec Act of 1774. Grenville said that the bill’s goal was to make each colony’s constitution like that of Britain.

Province of Quebec Divided

The bill had four main goals. First, to guarantee the same rights that other subjects in British North America had. Second, to give colonial governments the right to levy taxes to pay for local matters. This meant they would need less money from Britain. Third, to justify splitting the Province of Quebec (1763–91) into Upper and Lower Canada, each with their own legislature. And four, to fix the weaknesses of earlier colonial governments. This involved making the governor a true representative of the Crown. This boosted his authority and prestige. It also meant creating independent councils made up of appointed members. This would limit the powers of the elected assemblies. These appointed bodies were modelled on the British House of Lords. They were devoted to the interests of the Crown. (See also: Château Clique; Family Compact).

Foundation for Conflict

The Act guaranteed that owning land under the seigneurial system would continue in Lower Canada. It also created the Clergy Reserves in Upper Canada.

The Act gave Upper Canada a constitution and a separate legislature. It also favoured British settlement there. But the Act did not establish responsible government. It also gave more powers to the appointed bodies than to the elected ones. All these factors created political conflict. They led directly to the rebellions of 1837–38.

A Wider Franchise

Under the Act, voters were simply described as “persons” who were at least 21 years old and were “natural” citizens or subjects of the monarch. Voters were also required to own land or property of a certain value. (In urban areas, tenants could vote if they paid a certain amount in rent.) This property value was set quite low. The result was that a large amount of people could vote. Women were not excluded by the act. So women who owned property were allowed to vote in Lower Canada.

English Common Law was in effect in Upper Canada. As a result, women there were not allowed to vote. But in Lower Canada, women’s property and inheritance rights were decided by the Custom of Paris. Under French civil law, property was shared between husbands and wives. If the husband died, his widow received their shared property. As a result, women in Lower Canada had more access to property than anywhere else in the British colonies.

The Custom of Paris still applied to civil matters after 1791. Women who owned property in Lower Canada could vote under the Act. This was not always the case in practice. But between 1791 and 1849, women voted in about 15 districts in Lower Canada. In 1849, the legislature passed a bill that removed women’s right to vote. (See Women’s Suffrage.)

See also: Constitution of Canada (Plain-Language Summary); Responsible Government (Plain-Language Summary); Confederation (Plain-Language Summary).

Share on Facebook

Share on Facebook Share on X

Share on X Share by Email

Share by Email Share on Google Classroom

Share on Google Classroom