If you’re studying music theory and textures, you’ve undoubtedly heard of polyphony once or twice. But what is polyphony in music, exactly, and what importance does it have in the history of sound and composition?

Read on to know more about polyphony in music, including its rich history and influence on musical history.

What is Polyphony in Music?

Polyphony, also known as a counterpoint or contrapuntal music, is a formal musical texture that contains at least two or more lines of independent melody.

It’s believed to be the least popular among all three textures. Polyphony is often associated with Renaissance music and Baroque forms, such as fugue.

Origin and History of Polyphony

Although widely distributed across all known countries in the world, polyphony’s most significant influence is in regions of sub-Saharan Africa, Europe, and Oceania.

The origins of polyphony are the subject of many debates. Although unknown, the oldest written examples of polyphony are the treatises Musica enchiriadis and Scolica enchiriadis, both of which date back to C.900 A.D.

These treatises utilize two-voice note-against-note chant embellishments with parallel octaves, fifths, and fourths. Another example is the Winchester Troper, from C.1000 A.D, the oldest known extant example of chant polyphony.

Compared to monophony and homophony, polyphony is mostly improvised during the performance. Improvising performances is pretty common among professional musicians.

According to historians, polyphony relates to the development of human cultural music and the earlier stages of human evolution, the Homo erectus and Homo heidelbergensis.

They believed that polyphony stemmed from the melismatic organum, the earliest known harmonization of chant that developed in the Middle Ages.

In any case, polyphony was already heavily established during the 12th and 13th centuries, roughly between the Medieval period of 500-1450 and the Renaissance period of 1450-1600. Historical records of Greek and Roman antiquity further solidified this.

Polyphony’s Influence With the Church

Polyphony rose during Western Schism. Avignon, a city in France’s southeastern Province region, influenced sacred polyphony. At the time, Avignon was the center of secular music-making and the primary seat of the antipopes.

Polyphonic music, therefore, caused offense to medieval ears because merging secular music with sacred music is considered “taboo” and “uncultured” by the Papal court.

After all, polyphony sounded jocular and jagged, a stark contrast to the solemn melodies they were accustomed to.

For decades, the medieval church considered polyphonic music to be lascivious, frivolous, impious, and evil until the end of the 14th century.

In fact, polyphonic music was considered the devil’s music by the church for a time because it uses forbidden modes and instruments that clash against secular music rules and Pagan rites. Due to this, they banished polyphony from the Liturgy in 1322.

In the 1324 Bull Docta Sanctorum Patrum, Pope John XXII warns the people of the unbecoming and preposterous elements of polyphonic music. Even so, Pope Clement VI, who, at the time, was the head of the Catholic Church, favored and even indulged in it.

It was only when Pope Urban V came around in 1364 that the church finally authorized the use of polyphony in sacred music. This is all thanks to priest and composer Guillaume de Machaut and his piece, La Messe de Notre Dame.

How is Polyphonic Texture Achieved?

Polyphonic comes from the Greek words poly and phonic, which consecutively mean “many” and “sound.” It’s usually divided into two main categories: imitative and non-imitative.

Compared to monophonic, a musical texture with just one voice, and homophonic, a musical texture with multiple different voices, polyphonic is dense and complex.

Be that as it may, it isn’t rare to find simple polyphonic compositions. For instance, Row, Row, Row Your Boat, and Frere Jacques uses a type of polyphonic texture called canons.

Typically, polyphony adds a second, unrelated melody to a monophonic or homophonic texture. In Western music, polyphony includes a counterpoint separation of bass and melody.

However, these terms aren’t always mutually exclusive; several composers from the 16th through the 21st century use varied textures of rhythmically complex polyphony in the same piece to create a polyphonic texture.

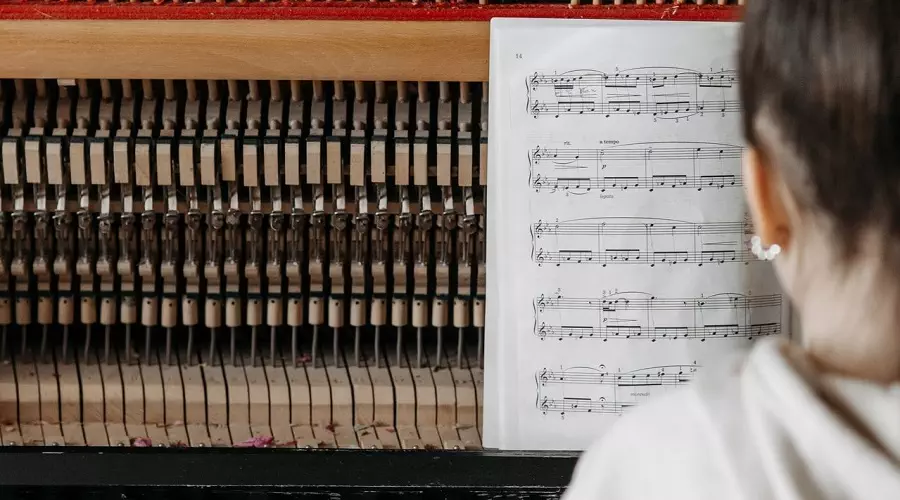

Polyphony is considered to be the most complicated musical texture because it challenges predetermined notions of harmony and melody.

Rather than the usual y-axis, polyphony puts its notes on the x-axis. Although playing the same melody, polyphony operates independently at different points.

Types of Polyphonic Textures

Canons, fugues, Dixieland, Heterophonic, and Iso, are five of the most common subtypes of polyphony. Let’s take a look at how each subtype differs from the other.

Canon

In music, you can achieve canon when you play a melody then play the same theme one or more times after a set period of time.

The least complex form of canon is called round, where the musicians only play identical or near-identical melodies.

Row, Row, Row Your Boat is an excellent example of a multiple-person round, with each individual singing his or her line four beats after the person before them.

Canons can also consist of melodies that aren’t musically identical to the original piece. For instance, Konrad Kunz’s Canon No. 114, a popular canon used for hand independence, plays a repeated rhythm pattern, with each hand starting on a different note as the song progresses.

Another personal favorite canon of mine is Pachelbel’s Canon in D; a popular piece played during holidays and weddings.

As you’ll hear in the original piece, the violin parts are played in three different periods. The second violin begins two bars after the first violin, and the third violin plays three bars after that.

Fugues

Popularized in the early 1700s, many believe that fugues are the defining musical styles of Baroque music.

Like canons in music, fugues imitate a melodic theme throughout a piece. However, unlike canons, the imitated melody or rhythm doesn’t have to stay the same as the original (leader) melody.

Fugues are a lot more structured than canons, as well. They have different, complicated sections and tend to last longer than a canon.

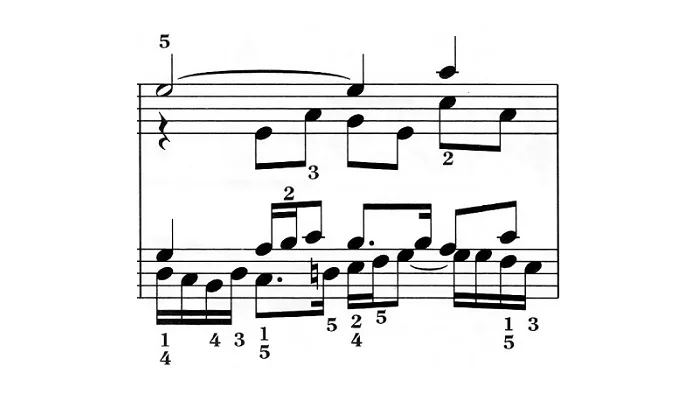

Johann Sebastian Bach (J.S. Bach), one of the most notable fugue composers of his time, wrote a brilliant fugue piece in The Well-Tempered Clavier, Fugue No. 17 in A-flat Major. Here, the right hand starts with a one-bar-long melody and goes from lower pitches to highest pitches.

Two semiquavers are followed by four quavers – twice in the right hand, three times in the last hand, then alternating between the two for several bars with lots of sharps or flats.

Heterophonic Polyphony

Heterophonic polyphony is achieved when a single melodic line consists of two or more variations. It’s similar to canon, or a round, except the song’s melodies are sung or played with extra variations and notes in between.

You can hear this type of polyphony in non-Western music, such as traditional Arabic, Japanese, Thai, Gamelan, or Turkish music. It’s also found in Baroque cantatas or oratorios.

In European traditions, you can hear dissonant heterophony in traditional music found in Bosnia, Croatia, and Montenegro – all attributed to the ancient Illyrian tradition of the Dinaric Ganga.

A relatively popular example of heterophonic texture is Mozart’s Piano Concerto No. 24 in C Minor. While the pianos and violins play the exact same melody, you’ll notice the occasional semiquaver embellishment weaving in between as the song progresses.

Heterophonic polyphony also appears in J.S. Bach’s A Mighty Fortress Is Our God (Ein Feste Burg ist Unser Gott) and Mahler’s Symphony No. 4.

Dixieland Jazz

Dixieland Jazz, also commonly known as Old-Style Jazz, Traditional Jazz, or Hot Jazz, is a style of Jazz that developed in New Orleans in the early 1910s and 1920s.

Like most Jazz music at the time, Dixieland Jazz consists of trumpets, trombones, and clarinets alongside rhythmic sections of piano, bass, guitar, and drums.

The main horn section plays different, unrelated melodies throughout the song over a two-beat rhythm, with the trumpet leading the piece.

Usually, the clarinet is played intricately; faster than the central trumpet, doodling up and down against the other melodies. The trombone is mostly heard in the background, deep, slow, and simple. Piano, bass, guitar, and drums serve as the song’s main body.

With all its intricacies, Dixieland Jazz is usually made up on the spot, improvised as the rhythm goes on. Popular Dixieland Jazz songs include Louis Armstrong’s When The Saints Go Marching In, King Oliver’s Dippermouth Blues, and Charlie Christian’s I’ve Found a New Baby.

Iso-Polyphony

Iso-polyphony is a type of traditional Albanian polyphonic music. The UNESCO (United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization) proclaimed that Albanian iso-polyphony is a “Masterpiece of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity.”

Iso divides into two major performance groups: the Ghegs of northern Albania and the southern part of Tosks and Labs. Iso-polyphony is related to incipient polyphony and drones – both of which accompany iso-polyphonic singing.

Musicians perform iso in two different ways. Among the Tosks, iso-polyphonic is on a continuous ‘e’ syllable with staggered breathing. With the Labs, it’s performed with a rhythmic tone between two-, three-, or four-voice polyphony.

What is Polyphony in Music: Conclusion

Music can be built with either one melody at a time (monophony) or multiple melodies playing together (polyphony). Polyphony is like a conversation between melodies, each with its own rhythm and character.

Over centuries, composers created complex forms of polyphony, like fugues and canons, where melodies weave in and out of each other, creating a beautiful tapestry of sound. It’s like multiple singers improvising together, but following specific rules to create a cohesive piece.