Andrew Jackson Biography: Seventh President of the United States

Who Was Andrew Jackson?

Nicknamed “Old Hickory” after the tough hardwood tree, Andrew Jackson was the seventh president of the United States, in office between 1829 and 1837. Although he had a successful legal career and was involved in public life for years, Jackson’s political career flourished only after he gained notoriety from his involvement in important military campaigns.

In the Creek War of 1813-1814, Jackson and his troops won the Battle of Horseshoe Bend, gaining control of vast lands that were formerly occupied by the Creek Indians. In 1815, he and his army defeated a much larger British force at the Battle of New Orleans. The event prompted his rise to power and transformed him into a national hero. In spite of his popularity, Andrew Jackson had to face numerous crises that threatened his reputation and the strength of the union during his presidency.

Although he was widely esteemed by Americans of his time, Jackson’s reputation has dwindled since the rise of the civil rights movement due to his support for slavery and his leading role in Indian dispossession after the signing of the Indian Removal Act in 1830. He is still admired for being a promoter of American democracy and for creating a strong presidency.

Early Life

Andrew Jackson was born in the backwoods of the Waxhaw River community in South Carolina on March 15, 1767. His parents, Andrew and Elizabeth Hutchinson Jackson, were Scots-Irish who emigrated two years before Andrew’s birth and settled in the Waxhaw region between South and North Carolina. Just a few weeks before Andrew was born, his father died in an accident. Finding herself unable to support the family, Elizabeth and her three sons moved in with their relatives. Due to his modest origins, Jackson’s first years of education were guided by local priests. He did not excel in school and did not have a natural attraction for academic pursuits, yet was a very active and strong-willed boy.

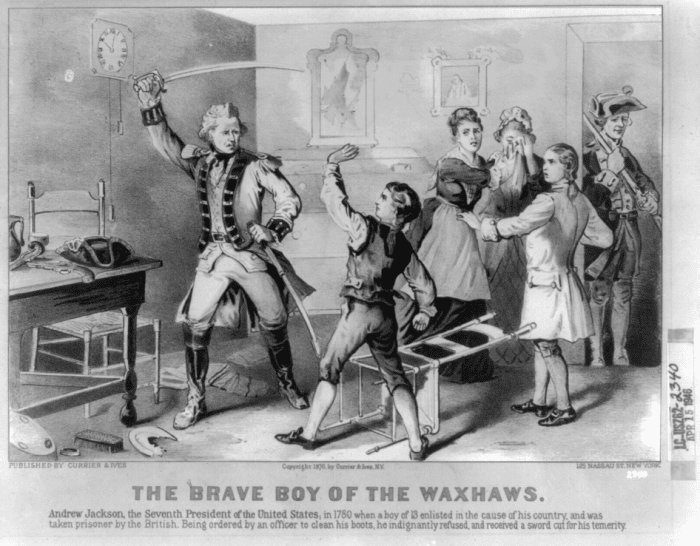

When the Revolutionary War started, Andrew and his brother Robert helped the local militia by delivering messages. In 1781, both were taken as war prisoners by the British and almost died of starvation. Andrew refused to shine the boots of a British solider and was badly beaten; the wounds he suffered would leave permeant scars on his face and body. Before their mother could secure their release, they contracted smallpox and because of their frail health and the terrible weather conditions, the journey back home was exceedingly difficult. Robert died within two days after their return, and Andrew remained gravely ill for several weeks. After Andrew recovered, Elizabeth volunteered as a nurse for American prisoners of war, but soon lost her life after being infected with cholera. Since his eldest brother Hugh had died in battle, Andrew Jackson found himself with no family at the age of fourteen. The crushing loss of his mother and brothers made him cultivate an intense hatred of the British. He also developed fervent patriotic and nationalistic values.

"The Brave Boy of the Waxhaws" depicts an incident in the childhood of Andrew Jackson, showing the lad standing up to a British soldier (as depicted a century later in an 1876 lithograph).

Early Legal and Political Career

After the Revolutionary War, Jackson resumed his education at a local school. He moved to Salisbury in North Carolina to study law in 1784. At the end of his studies, he won admission to the North Carolina bar and was selected for a prosecutor position that had just become vacant in the small frontier town of Nashville (now in Tennessee). There, Jackson became friends with Rachel Donelson Robards, the young married daughter of his neighbor, the widow Donelson. Since Rachel’s marriage was very turbulent, she wanted to divorce her husband. Slowly, she developed feelings for Andrew. Unaware that her divorce from Robards had not been finalized yet, Rachel married Andrew Jackson in August 1791. From a legal standpoint, however, their marriage was invalid.

Three years later, when Rachel’s divorce from Robards was finally completed, she and Andrew had to retake their vows. Although the incident had been the fault of Rachel’s ex-husband, the fact remained that Jackson had courted and wed a married woman, which was used against him by his political opponents for years to come. Jackson fiercely defended his wife’s honor, often with his fists and sometimes with duels.

In Nashville, Andrew Jackson quickly befriended some of the most affluent families in the area, which accelerated the advancement of his career. In 1791, he was appointed attorney general and his influence within the Democratic-Republican Party grew steadily. In 1797, shortly after Tennessee entered the Union, Jackson was elected U.S. Senator by the state legislature and thus became the state’s first congressman.

In Congress, Andrew Jackson assumed a radical, anti-British position. He had a strong antipathy for the John Adams administration and because of this, he found his job hardly satisfying, which compelled him to resign within a year. Upon returning to Tennessee, Jackson was elected as a judge of the Tennessee Supreme Court. Gradually, his legal career reached new heights and he earned a reputation for uprightness. In 1804, Jackson resigned his position, preferring to focus on personal ventures. His health had also deteriorated, forcing him to reduce his responsibilities.

While pursuing his professional goals in law and politics, Andrew Jackson amassed large tracts of land and expanded his activities to include several business endeavors. He built the first general store in Gallatin, Tennessee, and helped in founding several towns, including Memphis, Tennessee. In 1804, Jackson purchased a large plantation close to Nashville, called the Hermitage. He quickly became one of the most prosperous planters in the area and as he expanded his plantation, he increased the number of slaves in his ownership, going from 15 in 1798 to 44 in 1820, and more than one hundred by the time he reached the presidency. The slaves at Hermitage had living conditions that exceeded the standards of the time. Jackson also supplied them with hunting and fishing equipment and paid them with coins available on the local markets. They were, however, punished harshly for misdemeanor offenses and Jackson was notorious for his violent temper.

Military Career and the Creek War

By 1812, the conflict between the United States and Great Britain had escalated to formal hostilities. When the declaration of war was signed into law, Jackson fully supported the decision of Congress, sending an enthusiastic letter to the capital in which he offered a contingent of volunteers.

Convinced that the war was a great opportunity for his ambitions, Jackson personally led a force of more than two thousand volunteers to New Orleans on January 10, 1813, to protect the place against the British and Indian attacks. Things did not go as expected when, after a dispute with General Wilkinson, Jackson received a prompt order from the secretary of war to dismiss the volunteers and hand in his provisions to the general. Jackson stood his ground and asked permission to accompany his men home. On the way back, many volunteers feel ill and Jackson paid for their supplies from his personal funds, which almost caused his financial ruin but brought him the respect and admiration of his solders.

Recommended

A few months later, Andrew Jackson got his chance at military fame when he was ordered to regroup his volunteers and crush the hostile Creek Indians known as Red Sticks. On August 30, 1813, an alliance of Creek Indians attacked white settlers and militia at Fort Mims, north of present day Mobile, Alabama, killing hundreds. The attack on Fort Mims, and particularly the killing of civilian men, women, and children in the aftermath of the battle, outraged the U.S. public and prompted military action against the Creek Indians, who controlled much of what is present day Alabama. By November, Jackson had won the Battle of Talladega, but over the winter, his campaign suffered a severe crisis due to a shortage of troops. Many volunteers deserted or left as soon as their enlistment expired.

In March 1813, Jackson led around 2,000 soldiers to the south and confronted the Creeks at the Battle of Horseshoe Bend. Three weeks later, the Red Sticks were defeated and humiliated. The crush was so severe that the Indians found it almost impossible to recover. Following his victory, Andrew Jackson became major general and commander of his own military division in the U.S. Army. From his new position, he pushed for the signing of the Treaty of Fort Jackson, through which the Creeks, regardless of their involvement with the belligerent faction of the Creeks, were forced to pass millions of acres of land into the possession of the United States.

After the favorable end of the Creek affair, Jackson focused on defeating the European forces. He blamed the Spanish, who controlled Florida, for offering military supplies to the Red Sticks and for allowing the British forces to pass through Florida after proclaiming themselves neutral. On November 7, Andrew Jackson confronted an alliance of British and Spanish at the Battle of Pensacola, where his victory came quick and easy. Jackson discovered soon that the reason the British hadn’t put too much effort into the battle was that they were planning a larger attack on New Orleans because of the city’s great strategic value.

Battle of New Orleans

Andrew Jackson arrived in New Orleans at the beginning of December 1814 and quickly enforced martial law, fearing the betrayal of the non-white inhabitants of the city. Alongside his soldiers, he recruited volunteers from the surrounding states, placing military units all over the city. He managed to gather a force of around 5,000 people, but many of them had no military experience and had never been formally trained. On the other hand, the approaching British force consisted of 8,000 soldiers.

On December 23, the British force reached the Mississippi River, but was quickly repelled. The British retaliated with a major frontal assault on January 8, 1815, but the attack ended in a total disaster for them due to Jackson’s solid defenses and the loss of several senior British officers. The American force reported less than one hundred total casualties while the British suffered the loss of over two thousand. The crushing defeat forced the British to retreat, and the hostilities ended as the news of the signing of the Treaty of Ghent finally reached New Orleans and put an official end to the War of 1812.