Kid Congo Powers Interview: “Sorry, I’m a music nerd”

The garage-rocker chats about his new memoir, drug-addled days, era-defining bands and recent projects — and ponders the TikTok ascent of “Goo Goo Muck,” which he recorded in the Cramps.

by Brad Cohan

A funny thing happened between the time that rock ’n’ roller Kid Congo Powers first spoke with TIDAL and today: “Goo Goo Muck,” a killer garage-R&B cover that Powers released with psychobilly pioneers the Cramps in 1981, went TikTok-viral, thanks to a fantastic dance scene from Tim Burton’s hit Netflix series Wednesday.

Even in our post-“Running Up That Hill” music-media landscape, the ascendent “Goo Goo Muck” phenomenon is a surprise. But then so much about the life and work of Kid Congo Powers — singer, songwriter, guitarist, fashion guru, queer icon, DIY pioneer and all-around humble dude — has been astonishing.

The Mexican-American artist, born Brian Tristan in L.A. County in 1959, was schooled on glam rock before he discovered punk, which, hyperbole aside, led him on a life-affirming quest. A music super-fan from day one, he heard the Ramones as a teenager and launched a fan club dedicated to his NYC heroes. Powers’ record-collecting and gig-going obsession led him to cross paths with the likes of Jeffrey Lee Pierce and Lydia Lunch, both of whom urged Powers to play guitar. That suggestion became a career as a musician in three epochal bands: Pierce’s Gun Club, the Cramps and Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds. Informed by punk’s nihilism, free-jazz skronk and blues choogle, the self-taught musician earned a reputation as one of underground rock’s most charismatic guitarists. Since his tenure in those groups, he’s refined his garage-rockin’ power in various collaborations and at the helm of his long-running Kid Congo and the Pink Monkey Birds.

The rest, as they say, is history, documented in all its sex-drugs-and-punk-rock glory in Powers’ tell-all memoir, Some New Kind of Kick.

TIDAL caught up with Powers on Zoom from his home in Tucson, Ariz., to talk about the book, the classic LPs he played on and his recent bands and projects. We also followed up with him via email to get his take on the second coming of “Goo Goo Muck.” Those correspondences have been incorporated into the edited Q&A below.

What are your thoughts on the viral attention that “Goo Goo Muck” is getting all of a sudden, more than 40 years after Psychedelic Jungle was released? People are referring to it as the Cramps’ Kate Bush moment.

Well, it can only be good that the mainstream, and young people, know about the Cramps’ version of “Goo Goo Muck.” It’s a great teenage anthem. I also like the fact that the actor and dancer in this case, Jenna Ortega, is Chicana, and the guitarist who plays the opening chords of “Goo Goo Muck” is a Chicano.

What jumps out at you when you hear the Cramps’ version of “Goo Goo Muck” today?

Lux Interior’s amazing vocal performance: the changes in phrasing and wild jungle calls … and vocal car-crash noises were nuts. Really, it’s all rhythm that’s alluring and exotic. Poison Ivy’s spider-surf guitar solos for the win.

Guitar-wise, what did you bring to the table along with Poison Ivy on “Goo Goo Muck”?

I hold down the rhythm guitar throughout, swinging along with the coolest drummer ever, Nick Knox.

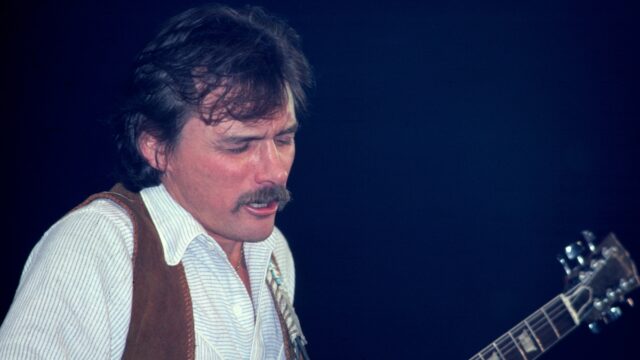

seen here at right with the psychobilly progenitors in the early ’80s. Credit: Rovi.

A major theme of Some New Kind of Kick is how joining bands like the Cramps, the Gun Club and Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds just sort of fell into your lap.

It was an amazing amount of luck and very right place, right time. I was lucky to start playing music in the dawn of punk rock. Everyone could do it, and that idea was king, and proficiency was … less. But in that you were able to learn, in a self-taught kind of way. Jeffrey Lee Pierce of the Gun Club just handed me a guitar and said, “Listen to this one chord of this Bo Diddley song and learn that and you’ll be fine.” He was right, and I’m still realizing that.

The book also threads the needle through the many music scenes and movements that you were deep in: L.A. punk, N.Y. punk, no wave, goth, etc.

The thing is I was a huge music fanatic. Music was my religion. I was looking for a tribe, really. I always think of music as communication, so I was looking for people that communicated with me and touched me. Music that made me excited and gave me hope and gave me identification, music that was beautiful to me.

I remember seeing Pere Ubu on their first tour, and I was crying. I really liked the invention of, say, the Contortions or the Cramps, of putting together different styles of music — the Contortions putting together free jazz and Albert Ayler with James Brown and punk attitude, or the Cramps mixing psychedelic music with rockabilly and having no bass guitar. It was not anything I’d heard about or even fathomed because it didn’t exist. So these kinds of things were exciting to me, and that’s where I followed.

Speaking of jazz, you write about how in the Gun Club you would delve into freakout jams on Coltrane’s “A Love Supreme” and Pharoah Sanders’ “The Creator Has a Master Plan.” Did you and Jeffrey get into jazz by way of the no-wave movement?

Well, that and a general love of music and R&B music and Black music. That is, for me, a holy grail of nonstop inspiration. Like, the Stooges were listening to John Coltrane … Jeffrey Lee Pierce as well was a big free-jazz aficionado, and the people we knew were bebop people and beatniks, so that music was just always there for us to explore. It was like finding a buried treasure.

For someone who thought they couldn’t play, that must have been demanding to play Coltrane or Pharoah Sanders, although I assume it was your own interpretation of it.

Jeffrey would always say, “Well, obviously we cannot play jazz. That’s not happening here. We’re a cowpunk band.” But when we made music, he would say, “Think like jazz. Just get a jazz mind and do that.” … The Gun Club did do a lot of improvisation and expansion — equally free jazz and Patti Smith “Birdland,” or whatever. These kinds of influences of just let it go, let it fly.

Jeffrey actually learned that horn line from “The Creator Has a Master Plan” note for note, so these challenges [expressed the idea that] “we love this music and we’re trying to create this picture and create these feelings and we want to hear a big swirl of sound that is not necessarily what you might think we want to hear.”

Related to that, you write that Poison Ivy said to play your guitar like a horn.

Like a saxophone — very percussive, very horn-like, a lot of bomp-ba-bomp and a lot of just let loose with a wail. That made sense to me. As a self-taught person, if someone said, “Play a D-seventh-diminished chord,” I wouldn’t know it. Actually, I would now, but at the time, no. So I like these other ways of approaching guitar. It was more fun for me, and it made more sense to me. It was, in some ways, an easier road, because that was a language I understood.

When you were writing the book, did you revisit the classic albums that you played on, like Psychedelic Jungle? What struck you about that one over four decades later?

Pretty good! [laughs] These realizations like, “Oh, wow. You played really well,” and, “Did that really happen?” The book brought me back, and I’m always the super-fan. At the time I couldn’t believe the Cramps would ask me to be in their band, and I was really expecting to just fill in on a Bad Seeds tour and that would be it — just two weeks of shows. All of this was very fortunate.

I listened to a lot of the music and, more recently, I did a podcast where we listened to all of Psychedelic Jungle and went through it song by song. That was pretty eye-opening, to remember what was going on with that.

But I had to write about [these recordings]. I had to know, what was the feeling going on? And it would spark pictures of us in the studio and who was doing what. A lot of it was reliving and kind of Method acting, really. And the stories.

Was it a daunting transition to go from the Cramps and the Gun Club to playing in the Bad Seeds?

No, it made complete sense. I think they were bands that were kindred-spirit type of bands and had great admiration for each other, Jeffrey Lee Pierce and Nick Cave and [the Bad Seeds’] Mick Harvey and everyone else. [The Bad Seeds] knew how good the Gun Club was, and that bonded those bands — a distinct vision and an unwavering vision, and that creates mutual admiration. For me, one informed the other. They were separate types of music, but I could see that it was not so far a stretch to do both bands.

You detail in your book that the period when you recorded Tender Prey in Berlin was pretty dark, as far as substance abuse is concerned.

Personally, very dark. [laughs] It was a time of a lot of drugs, and that whole extreme, staring-into-the-abyss type of living was starting to not work for me and the people around me. People were starting to realize it was not productive.

And that’s the thing, that despite all of the drugs … [laughs] It’s interesting to think of that Lou Reed song [starts singing the lyrics to “Kill Your Sons”]: “All of the drugs that we took / It really was lots of fun / But when they shoot you up with Thorazine on crystal smoke / You choke like a son of a gun.” Sorry, I’m a music nerd.

But for all of the drug taking and antisocial behavior, when it came to making records and music, everyone was very focused, everyone I worked for and with. That became the most important bit. Making a good record was the focus, and we could see that the drugs were taking the focus away, and that was scary.

Drugs were disrupting the creative process.

I was feeling like, “Now I’m in the Gun Club, I’m in Nick Cave and the Bad Seeds, I live in Berlin, I’ve never had more opportunity and popularity and I don’t give a fuck about it. I want to get drugs. And if I can keep that going, it’ll keep me straight enough to do whatever.”

But as far as inside, I kind of turned to stone and really didn’t care. So it was a really scary moment to realize that, but also, ultimately, a good moment. It was good because a lot of people in my tribe were feeling the same thing.

Just two years later, The Good Son signaled a major turnaround, personally and creatively, for you and for the band.

The music changed. The people who got clean, we all started saying, “Oh, wait, we’re somebody else. [laughs] We have other desires and we can realize them. We can have a life outside of taking drugs and making music.” That definitely changed the tone of everything — that you can feel something other than intensity.

Of course, your memoir is titled after a Cramps song, “New Kind of Kick,” and lyrics from that song open the book — words that you’ve worn as a badge of honor throughout your life.

That is an anthem for the book and the anthem for my life. And that was the anthem for the Cramps’ life as well. “By the age of 9 / But I could better myself / If I could only find / Some new kind of kick.” I was trying to think of which quote to use. That’s what I thought when I wrote the book: Well, that’s what this book is about. I was just looking for excitement. I was looking for it anywhere I could find it.

From the youngest age I was completely single-minded about music. I was a baby who could [identify] records by the label before I could read. My whole education was through music. … Really, there was no other choice. I didn’t know if I was going to be a musician. I was going to be a journalist perhaps, or an A&R person. I just thought, “How can I get free records and have a job?” But mostly, “How can I be around music?” That is what I know and what I know I want and what feeds me. It keeps me engaged and keeps me curious and keeps me looking for something else.

Besides Some New Kind of Kick, you’ve also released two new records with two different groups. How did Live in St. Kilda with the Near Death Experience come about?

My friend Kim Salmon, who’s in the band the Scientists, was doing a book-launch concert and asked me to come. Kim and his biographer decided I would be a good choice. They couldn’t afford to bring my whole band [the Pink Monkey Birds], so I said, “Well, let’s use Harry Howard’s band, the Near Death Experience.” So that playlist is a bunch of songs I thought Kim would like … the Shangri-Las, Alan Vega and Suicide. These are bands I know he loves, so it’s all songs for Kim.

Then there’s the Wolfmanhattan Project. This group has a new record, Summer Forever and Ever, and you’re reunited with drummer Bob Bert, who you go way back with.

Way back … to the troglodyte days. [laughs] I played with him in a band called Knoxville Girls in the ’90s. I know him from when he was in Sonic Youth, really, and Pussy Galore. I’ve just known him forever and he’s one of my brothers. I’m a big fan of Mick Collins from the Gories and the Dirtbombs. I love his singing, his guitar playing and what a weirdo and great mind he is. I said, “We should do something together.” We’ve played about five times and this is our second record. [laughs]

But that’s the great thing: We just do it because we love playing together. I like this album a lot because it sounds like we’re playing together. I felt a little bit like the first album was everyone’s solo stuff, like, “Oh, there’s Kid songs, Mick songs and some Bob songs.” This one sounds like our songs.

How do you see the Wolfmanhattan Project and your own band?

They inhabit the same world, but they inhabit different parts of my brain and desires. The Pink Monkey Birds has become a beast of its own, really; it has its own life and it’s very much a collaborative band, with drummer Ron Miller, guitarist Mark Cisneros and bassist Kiki Solis. We all come with our pieces of what we want to work on, and it just metamorphosizes from there. Wolfmanhattan is kind of the same deal. It’s about the alchemy of the people. It’s just a joy playing with good people.

It seems like your influences and your roots all come together in the Pink Monkey Birds.

It’s a culmination of everything. It really found its freedom, actually, the last time I saw the Cramps, one of their last shows. I was watching them and I hadn’t seen them for 10 or more years. I was watching it and my jaw was on the floor. Then I was like, “But wait — it’s just the same three chords. Why does it sound like it’s from outer space and heaven and so different from everything else?” Then I just thought, “Oh, it’s them.” It’s the alchemy of them, and it’s what’s coming through their fingers and voice. Everything is them and the freedom they have in their expression. That’s what’s making it happen, and that’s what everyone’s relating to.

Then I thought, “Wait. I’ve been a part of this.” I know how to tap into that, but I just hadn’t because [my attitude had been] “I don’t want to trade on that old stuff and look back.” But I thought, “I can do that. I can trade on all I’ve learned and what I’ve been involved in.”

You had a revelation.

And this is the thing with the book. It was like, “OK, you don’t have to hide anything since this is really what happened.” If you think of Nick Cave and Jeffrey Lee Pierce, these were all people who had very strong visions of what was going to happen, and did not pander to record company pressure or [pressure] to make a hit or even to public opinion about them. The Cramps [were the same way]. This is a philosophy that is a good one — stay true to the muse and don’t fuck with it.