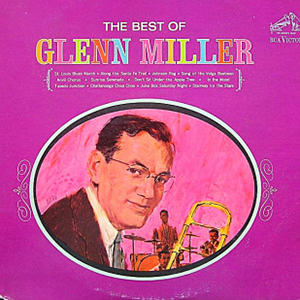

Not one friend my age, when growing up, understood my youthful passion for the music of Glenn Miller. It wasn’t that he was an enigma, or that his band belonged to another generation, although that probably had some play in it. The real reason was that they didn’t hear what I heard: the workings of a superior mind, both in terms of musical construction and orchestration, in the often ephemeral popular tunes of his day.

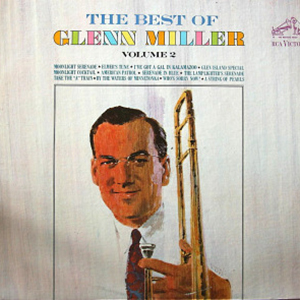

By the time I was 18 years old, I had a massive Glenn Miller collection. It had started with the two “Best of” albums that RCA Victor issued in 1965 but then mushroomed into the three single-LP releases of “Glenn Miller on the Air,” the two five-LP deluxe fold-out book sets of a mixture of unusual commercial recordings and live broadcasts, a couple of RCA Camden releases of commercial discs, the five-LP set of his Army Air Force band, two albums’ worth of his film soundtracks for 20th Century Fox and another, three-LP deluxe RCA set of rare broadcasts. To say I was hooked would be putting it mildly.

|

|

Of course, in time I fell away from most of this, realizing that along with the pearls in these collections came the chaff as well. Perhaps my biggest disillusionment was to hear, years later, the Chesterfield broadcasts that the band gave with the Andrews Sisters. Never had I looked forward to a Miller set as much, but his arrangements for the Andrews were routine and predictable, sounding more like generic charts than anything played by the Miller band. I was sorely disappointed.

But what exactly was it that drew me like a moth to a flame when it came to Glenn Miller? Several things. First, and probably most obvious, was that irresistible clarinet-led reed section blend, which even as stringent a critic as Gunther Schuller called the most hypnotic sound in Western music. But if that were all, I would have been just as impressed by the Miller-imitation bands led by Bob Chester and Ralph Flanagan—yet I wasn’t, because there was more. There was his use of ooh-wah brass, not an original device in itself but masterly in the way he used them. There were his brass smears, his absolutely brilliant juxtaposition of reeds and brass, his use of a completely interlocking rhythm section that played as if by one man with four instruments (Schuller also mentioned this), and—last but not least—his innovative and, I would say, unique use of rhythmic and harmonic devices that “built” up each arrangement and made them perfect little jewels that had a beginning, a middle, and an end, just like a good piece of classical music.

DG5CBD

As the years and decades passed, I realized that I was not the only one to notice these things. Schuller, a fairly unpleasant egotist who nevertheless had a fine musical mind, was probably the most noted jazz scholar to agree with me, but I had the actions and attitudes of others who I either discussed Miller with personally or read about in articles and books who felt about him the same way I did, to wit:

- Classical conductor Keith Lockhart, current director of the Boston Pops Orchestra but former associate conductor of both the Cincinnati Symphony and Cincinnati Pops orchestras. When he was asked to put on a concert of Miller’s music with the latter, he had no more than a passing acquaintance with Miller’s music, probably by hearing In the Mood and Chattanooga Choo-Choo a few times. But when he started digging into Miller’s scores of such old 1920s tunes like Runnin’ Wild, My Blue Heaven and Pagan Love Song, he was literally stunned by the technical difficulties these scores called for; and, upon hearing Miller’s original recordings, was more than a little shocked that he could get young musicians of his day, many without any real formal training, to play these scores.

- Jazz clarinetist Buddy de Franco who was, for a time, leader of the Glenn Miller “ghost” orchestra during the 1960s and early ‘70s. When I saw him leading the Miller band in one concert, I went up and talked to him afterwards. He told me that, as a member of the rival Tommy Dorsey orchestra in the 1940s, he thought that the Sy Oliver charts he played with Dorsey were superior to Miller’s, but that now he was actually involved in performing them he was amazed at their “harmonic subtlety, rhythmic ingenuity and overall musical concept”—and he agreed with me that, although he liked playing pop hits of the day in the “Miller style,” no one could arrange the music with Miller’s deep knowledge and understanding of what made it tick.

The late jazz pianist Jack Reilly, who worked with the Modernaires (Miller’s vocal group) for a few years and, like de Franco, was startled by the musical sophistication of Miller’s original scores when he actually had to play them. - Vet Boswell, the last surviving member of the legendary Boswell Sisters jazz singing group, who told me on the phone how Miller, hired as second trombonist on one session, was able in “less than 15 minutes” to completely revamp the arrangement of Alexander’s Ragtime Band from a fairly mundane thing into a masterpiece of musical construction, including a completely original introduction and a two-trombone chorus (played with Tommy Dorsey) that had brass punctuations throughout. (The discographies all list Chuck Campbell as second trombone on this session, but when I told Vet that she exploded at me. “Don’t you think I’d know Glenn Miller when I saw him?” she snapped. “Of COURSE it was Glenn Miller!”)

- Jazz legend Bobby Hackett, who played both cornet and guitar with Miller’s band in its last two years, told Whitney Balliett of The New Yorker that Miller was a “genius” at being able to tweak a score, even those not written by him. “He’d listen to a new [arrangement] and suggest a slightly different voicing or a different background behind a solo, and the whole thing would fall suddenly into place.”

- Louis Armstrong used to carry around a reel-to-reel tape of Glenn Miller recordings and another of Tchaikovsky symphonies, which he played for himself all the time when on the road.

But Miller only arrived at his final form of 1938-44 by trial and error, although the recorded evidence proves that he was an innovator early on. While with the Ben Pollack Orchestra of the late 1920s, he was for some reason only occasionally allowed to write real jazz arrangements, though he did (Waitin’ for Katie and Yellow Dog Blues are two of the best). Once the “society” jazz band of Roger Wolfe Kahn became a big hit with its smooth-but-swinging arrangements that used a few strings in the mix, Pollack sent Miller to go listen to that band for a few nights and come up with some similar arrangements, which he did (i.e., Buy Buy for Baby). His real first liberation came when working as a free-lancer for Red Nichols and his Five Pennies in 1928-32. It was during this period that Miller came up with one innovative score after another, using a multitude of techniques such as an expanded Dixieland sound (Indiana, Dinah), a prototype Big Band sound using eight instruments like a full orchestra (Rose of Washington Square) and even using Benny Goodman’s clarinet like a flute fluttering above the winds, later to move into a boogie-woogie beat for Carolina in the Morning. Nothing seemed too daring or original for him; he just kept trying out one new idea after another.

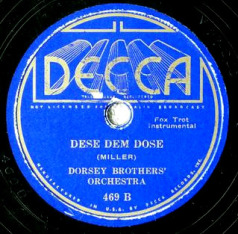

By the time he worked with Tommy Dorsey and the Boswell Sisters in 1934, Glenn was already chief arranger and second trombone with the then-full-time Dorsey Brothers’ Orchestra. Tommy especially liked Miller’s expanded-Dixieland sound, so that’s what he stuck with, writing a full-band version of King Oliver’s Dippermouth Blues, a cute original tune called Dese Dem Dose, Jelly Roll Morton’s Milenberg Joys, and a six-minute arrangement of Honeysuckle Rose. By the time the Dorsey Brothers’ Orchestra broke up in 1935, Miller’s reputation as a jazz arranger had grown substantially. One story that trombonist-vocalist Jack Teagarden never tired of telling until his dying day was how Miller wrote a completely new extended introduction to Basin Street Blues for one of Jack’s Charleston Chasers sessions, the section that begins “Won’t you come along with me…Down the Mississippi…We’ll take a trip to the land of dreams…Steamin’ down the river to New Orleans.” Teagarden always felt that Miller should be listed as co-composer of Spencer Williams’ song, since everyone in the world sang or played that intro as part of the tune forever and ever, but Miller modestly waved it away as just another day’s work.

By the time he worked with Tommy Dorsey and the Boswell Sisters in 1934, Glenn was already chief arranger and second trombone with the then-full-time Dorsey Brothers’ Orchestra. Tommy especially liked Miller’s expanded-Dixieland sound, so that’s what he stuck with, writing a full-band version of King Oliver’s Dippermouth Blues, a cute original tune called Dese Dem Dose, Jelly Roll Morton’s Milenberg Joys, and a six-minute arrangement of Honeysuckle Rose. By the time the Dorsey Brothers’ Orchestra broke up in 1935, Miller’s reputation as a jazz arranger had grown substantially. One story that trombonist-vocalist Jack Teagarden never tired of telling until his dying day was how Miller wrote a completely new extended introduction to Basin Street Blues for one of Jack’s Charleston Chasers sessions, the section that begins “Won’t you come along with me…Down the Mississippi…We’ll take a trip to the land of dreams…Steamin’ down the river to New Orleans.” Teagarden always felt that Miller should be listed as co-composer of Spencer Williams’ song, since everyone in the world sang or played that intro as part of the tune forever and ever, but Miller modestly waved it away as just another day’s work.

Last modified: May 29, 2019