Big Nate, Small Screen: An Interview with Lincoln Peirce

Note: Throughout the interview, click on an image to enlarge it.

Comics fans have seen Lincoln Peirce’s Big Nate in newspapers since 1991 and in an expanding line of books in the years since then. But this month, Nate Wright and company are making the leap to television animation with a streaming series on Paramount+ premiering on February 17. (The series is being produced by Nickelodeon Animation Studio.) Hogan’s Alley editor Tom Heintjes recently spoke with Peirce about his experiences in adapting his work to animation.

Tom Heintjes: Well, Lincoln, it's a pleasure to talk to you. I’ve looked forward to this opportunity ever since Molly [Neuhauser, of Nickelodeon] brought it to me. I have a few questions I want to ask you about your career leading up to the Big Nate animated project, and some questions about what you're doing with it now.

Lincoln Peirce: Sure.

Heintjes: You've worked in some form of print storytelling books and comic strips for many years now. What were some of the challenges of animating Big Nate and thinking about him in a new medium—what was, for you, a new context for the character?

Lincoln Peirce

Peirce: Well, the first challenge for me, Tom, I think, was imagining Nate in any other visual form besides just 2D, because I've always just drawn him the old-fashioned way, pen on paper. And at times when I tried to imagine him in three dimensions, I found stumbling blocks. I thought, “How could you make Nate's hair in three dimensions? How could you build a character and make it work in three dimensions?” So, I would characterize myself as a skeptic about 3D animation, specifically, for Big Nate because he's always been a two-dimensional character. So that was one of my, I guess, concerns or misgivings going forward.

Another one was that I've always been a one-man shop. I've never worked with anyone else. I've never collaborated with anyone. And so I thought, what's it going to be like when I inevitably work with other writers, when other writers are coming up with story ideas, when other people are designing my characters, when a casting director is sort of making the decision about who's going to voice these characters? So, I didn't really know what any of that would be like. And it's all been great, I’ve got to say. I’m delighted with the way everything is working out. And I think that is really a tribute to Nickelodeon, and the fact that they are really, really good at what they do. This is obviously not their first rodeo, and they're I think good at taking things from other source material and sort of making it their own. And in this case I am thrilled with how faithful an adaptation this is of Big Nate. And at the same time, there's a lot of sort of room for it to become more and different from Big Nate, too, because you can do so many things in animation that you can't do in four panels in the morning newspaper.

Heintjes: Actually, I want to touch on a couple of those themes shortly. But first, how did the opportunity to animate Big Nate come around? How did it come to your doorstep?

Peirce: Well, basically for the first 18 years of Big Nate, the comic strip, it sort of was on a flat line. It wasn't going down, but it wasn't going up. And like all cartoonists that I've ever met, I thought if only I could find a way to get in front of more people, especially kids. And so what happened with that was I had the opportunity to start writing Big Nate novels, and the novels were what sort of increased my audience and increased Big Nate's profile. And so shortly after I had started writing those novels, we started getting offers about maybe movie projects or TV projects, but they were all about live action. And so at a certain point, a producer named John Cohen wrote a letter to me. And I didn't know him, but he was, he had had some credits on the Despicable Me movies, and was at that time about to start producing the first Angry Birds movie.

The animated Nate surrounded by artwork done in Peirce’s own style.

Heintjes: So obviously, a great deal of credibility.

Peirce: He wrote me the loveliest letter that told me what he liked about Big Nate and why he thought it would make a great animated project, and why he thought it could only exist in animation and not in live action. And so we made a handshake deal with him. He sort of became our rep to shop Big Nate around. And he did that and it took a while, but he eventually found a partner in Nickelodeon. And so that’s how it came to me. It came to me really from the result of John Cohen's hard work. He took a lot of meetings, and he made a lot of pitches, and that's how that's how it came about.

And then Nickelodeon assembled what to me was like a dream team of people that I could have worked with. Mitch Watson, who is one of the executive producers, is the show runner, the head writer. He's great. And then David Skelly, who is the art director, and really created much of the just the look of the characters, the character designs, the set designs, and I just felt in such good hands when I first met them. And of course, I still haven't met any of them in person. This has all been virtual. Everybody's just working from their own parts of the world.

Heintjes: Well, it's funny you mentioned that. I was just going to ask you—you mentioned how you worked alone for all these years. And cartooning and writing in general is a very solitary activity. Animation is quite the opposite, you know. It takes a small army, often on different continents. What was that very collaborative environment like versus what you've been used to for so long?

Peirce: Yeah, it was super different. But it was really comfortable, I have to say. I mean, I guess I'm listed as a creative consultant on the show. And what that has ended up meaning is that that they have a great writers’ room on the show, they come up with story ideas. They'll write a first draft, and then they'll send it to me. And so my contribution is what they call doing punch-ups. I sort of work to punch up the scripts, I try to add jokes where I can, I try to sort of align the dialogue more with the way that I think the characters might speak, if they have a certain way of speaking, and the collaborative nature of that means that I know that they're going to use some of what I suggest and not use other things that I suggest, and that's fine with me. I'm happy as long as I sort of am able to sort of take a swing at it. And I think it really having not collaborated before, I think I kind of underestimated how important it can be just to sort of workshop some of this stuff and how much stronger you can make a script when five different people are sort of looking at it as opposed to just one set of eyes. So yeah, it's been sort of a revelation, and I think it's been enjoyable.

Heintjes: It sounds like you've also really flexed some different creative muscles in the process.

Peirce: I think so. Yeah, it is really different to essentially to look at something someone else has written as opposed to something that you've written, and then sort of rewrite that or tweak it or something like that. It's just a really kind of different experience, because you don't know for certain what the person was thinking when they wrote this particular piece of dialogue or this particular scene. And sometimes, and this has also been entirely new to me. Sometimes something just won't really grab me on the page. I'll think, “Well, is that really going to work?” But then either because the animation looks so good or because the vocal performance is so funny, all the sudden, this gag that maybe seemed like sort of a C-plus on the page is an A-plus. So that's fun, too. And I didn't really know anything about that, just working alone on the comic strip or on the books.

Heintjes: Let me ask you about some of your own favorite cartoons from when you were a kid or up to now. What shaped your thinking about what makes a good cartoon?

Peirce: Well, my go-to when I was a young boy was the old Max Fleischer Popeye cartoon.

Heintjes: Oh, that's cool!

Peirce: Yeah, there was a local TV show…I grew up in New Hampshire. There was a local TV show that had a genial host, and he had a live studio audience of some local kids. And he'd show some cartoons in addition to playing some little games. It was sort of like a Bozo the Clown kind of a show, but they always showed a couple of Popeye cartoons. And I loved them, and of course as a young kid I had no idea that Popeye was a comic strip character who had been transformed into this animated character. I didn't know what Thimble Theatre was or anything like that.

Heintjes: Right.

Peirce: I just loved Popeye. And one of the things I loved about those cartoons was just the absurdity of them. I thought it was just so surreal, as a young kid, that Popeye was so enamored of Olive Oyl. I said, essentially, what does Popeye see in Olive Oyl? [laughter] And then, of course, I loved the little guy against Bluto, against like the big guy. And I loved the vocal performances. I was really just in love with all those voices of those Popeye cartoons. And then later on, I was all about the Looney Tunes. I loved Bugs Bunny. Bugs Bunny is one of the all-time great characters. And I just watched those religiously, and you probably had the same experience when you're plugged into comics and cartooning in a way that's maybe different from your friends, and you're all watching cartoons together. You notice things that your friends don't notice. They're just watching a cartoon while you're watching it with the eyes of someone who, even at a young age, this is sort of in your DNA. And so you say, “Can't you tell that that's just the same cactus going by in the background?” And they're like, “What are you talking about?” Or you say, “Can't you tell that this Looney Tune is probably from about like late ‘40s, ‘48, ’49?” And they're like, “What do you mean?” And I’m like, “Can't you tell Bugs at first is a little darker than he is later, his dimensions are a little different?” And they're looking at you like, “You're crazy.”

Heintjes: And they might be right.

Peirce: Yeah, but you notice these things. And then later on, of course, I loved Bullwinkle and Rocky. I think Bullwinkle and Rocky is, from a writing standpoint…the animation was really fun to look at too, but it was very simple. But from a writing standpoint, Bullwinkle and Rocky was phenomenal, and I loved it. So I put those as my big three: Popeye, Looney Tunes and Bullwinkle and Rocky.

Heintjes: Well, I must say you have outstanding taste in animation. You mentioned that Popeye voices and all the characters’ voices. That's an excellent segue to a question I had for you. Every cartoonist hears his characters as they write. You have voices in your head, if you will. So, what was it like for you to hear your own characters? Were you involved in casting voices, or how did that evolve in terms of how they actually speak?

Peirce: I was involved in casting voices, but I will say I may be a little bit different than some other cartoonists who have gone through this process in that I definitely the dialogue over the years when I would be working on the strip of the books. I heard the dialogue inside my head, but I didn't really hear specific voices so much as I just I hear my own voice saying the dialogue. You know, it sounds boring, but maybe I'm just not imaginative enough to sort of really sort of manifest the voices inside my head. I really didn't go into this with a clear idea like, “Okay, is Nate's voice going to be husky? Is it going to be high? Is it going to be low?” I really didn't know.

And so when I heard some of the auditions, I thought, well, maybe something will really just jump out at me. And in fact, for almost all the parts, Nickelodeon would usually kind of cut down the number of people so that by the time I listened, I was listening to—I don't know, half a dozen or so. And in fact, in most cases, there were two or three possibilities where I thought, “Yeah, this person would be good.” The one exception to that is the voice of Nate. I thought Ben Giroux, who ended up being our Nate, was head and shoulders above anyone else I heard. But it wasn't because he spoke the voice I had been hearing in my head all these years. It was because there was just something in the quality of his voice that I thought made him a perfect match.

Heintjes: I also want to talk about character design. In animation, that's a very specialized skill and, I think, a very underrated skill. What was involved in capturing your characters—your very distinctive-looking characters—in an animation context, turning the, the things that have to happen? Was that a tough process or an easy one?

Peirce: The design went fabulous thanks to Dave Skelly, who is our art director, and the others who were working with him. He sometimes called them characters, sometimes he called them puppets. One of the things that we talked about when we first met one another was 3D animation, sort of like the Rankin/Bass Christmas specials, that sort of look a little bit choppy, a little…it's not claymation, but it's got sort of that stop-action look. And that was something that we really liked specifically for Big Nate, and we talked about a lot that. And I remember early on doing some drawings, some turnarounds, where I just made drawings of some of the characters from a bunch of different angles. I made some drawings of like mouth positions and things like that, but then they were doing tons of research independent of whatever I was supplying them with. They were reading all the Big Nate books, they were looking through the archive of past strips and really trying to look at the way that I drew the characters in different poses, different situations, and try to incorporate that. So I would say I contributed in a very small way, but I think the characters ended up looking as great as they do because Nickelodeon is really good at what they do. Like you said, character design is such a specific skill, and it's obviously one that they're really, really good at.

Heintjes: Did you look make actual old-school model sheets or anything like that, that they referred to?

Peirce: I did some what they call draw-overs, sort of like turnarounds or walk cycles, things like that. And I think they use those to some degree, but I also think it also it helps them to see where they're going to have to make some changes because, as you know, a lot of times when you're drawing in 2D, you have little cheats. You have little things that work because I'm drawing them in 2D, but if I ever tried to create a 3D model of this, it just wouldn't work. Like when Nate walks and the toes of his front foot point up, I have to shorten that foot because if I drew it as long as his plant foot, it would come up practically to his chin. So they realize that there were a lot of inconsistencies in the way that I draw. And to their credit, they didn't like make me feel bad about that. They didn't say, “Oh, my God, what have you done?” They just work with what they had, and they found ways to accommodate, I think, the look of Big Nate while creating these consistent models, these puppets that that could exist in the round. Like I said early on, I didn't know that they'd be able to do that.

Heintjes: Well, we all know the self-esteem of a cartoonist is fragile enough, so, it's nice that they didn’t point that out. But I had the opportunity, thanks to Molly, to watch some episodes in advance of our conversation, and I really enjoyed them. And one of the things I noticed is that each episode had this snippet—maybe just a few seconds—of a classic rock song. There was Boston and Simple Minds and Peter Gabriel. Was this to bridge generations? I just thought it was a nice way to talk to different generations.

Peirce: I love that about it too. And I have to plead almost complete ignorance on this, because I don't quite know how it all works with how you get rights to certain songs, and how much of the songs that you can play. But I remember when we were working on the pilot. The pilot ends with like a very sort of specific song sort of sting, and in the animatic they played the actual song, and I remember thinking, “Well, they're just using that as a placeholder. There's no way they're going to be able to like put that song in our cartoon.” Can they? And in fact, yes, they can. And it's one of the things that I love about drawing the strip. I draw it for all ages, and there are things within the strip that I think will resonate with older readers or middle-aged readers or whatever. But hopefully, there's still enough in it that young kids will enjoy it. And amazingly, to me, there's still a lot in the show where the show is much more specifically geared toward a kid audience, obviously. But we want it to be the sort of show that if mom and dad are sitting down next to the kid watching it alongside, that there's going to be plenty in there for them too. And I think the music is part of that.

Heintjes: Well, in the first episode, I think that's where I heard Don't You Forget About Me by Simple Minds—again, like three seconds of it. But when you're watching it and you hear that, it's like it really gets your attention because it's so old school and came out before these kids were born. So, thought it’s a great way to sort of tie together different audiences.

Peirce: I think so too. Yeah, I think you're right, and it hits you in a way that it wouldn't hit you had they needed to create a generic little piece of music for those same three seconds. The fact that it's the original sort of makes it kind of seem special in a way.

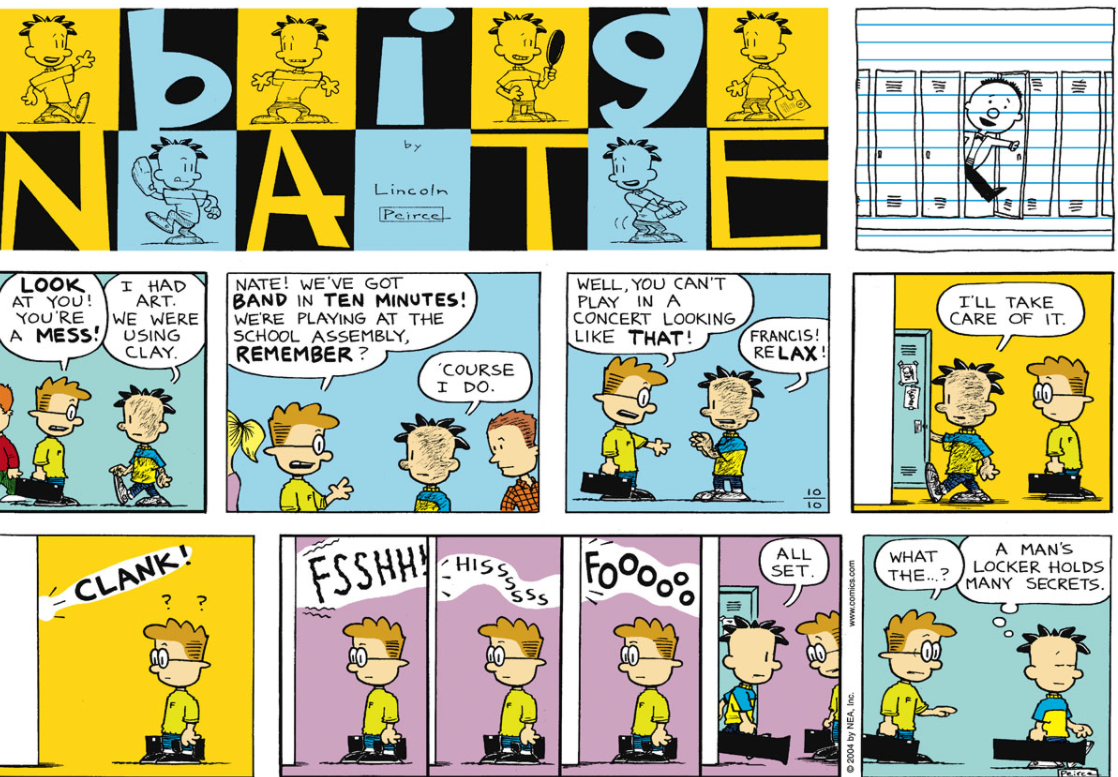

Heintjes: Each episode also features segments with work done in your own print style, which I thought was nice homage to the character’s roots. As someone who began as a print cartoonist, how did it feel to see some of your own drawings in a totally different context? There had to be kind of a real kick for you as an artist.

Peirce: Yeah, absolutely. I mean, I was delighted. You know, in one of our very first meetings, I remember saying to Mitch Watson, the head writer—sort of almost as if I was dreading the answer—“Now, are you planning to do some stuff with Nate's comics and Nate's notebook world? Because, to me, that can be like a really entertaining part of the show and of Nate's sort of worldview and the way he looks at things.” And right away, Mitch said, “Oh yeah, we have plans to do some really fun things with other types of animation within this 3D world that we're building. There's going to be some 2D animation, there's going to be some Monty Python–esque, almost collage animation that will coincide with maybe like a little fantasy segment or the way that another character might see a certain situation.” And I thought, that's great. I think that works really well in the show, and I think it just creates that many more storytelling possibilities.

Heintjes: At the end of the episode, there's a human hand drawing. Is that your actual hand?

Peirce: That is my actual hand, yeah.

Heintjes: Great! I wondered if you had a hand model or if that was you.

Peirce: No, that's me. My wife took like two dozen pictures of my hand, and I sent a bunch of them to Nickelodeon and they chose one. And at a certain point, they said, “Would you be willing to create a strip for us to use during the end credits for each episode?” I said yeah, so the strips that you see at the end, with my hand drawing them, are just jokes that I wrote that are sort of inspired by the episodes, but they don't specifically correlate to the episodes. But they're fun. I think it's a nice kind of tribute to the origins of Big Nate, that there's this four-panel motif at the end with the end credits.

Heintjes: I thought it was cool.

Molly Neuhauser: Tom—sorry, just jumping in here to let you know this should be the last question.

Heintjes: Oh, darn. Okay. Lincoln, we’ve talked a lot about your experience with the program. How does it compare to what you would have imagined? Everybody hears nightmare stories about notes from the studio, notes from executives. What's your experience been versus what you imagined it might be like? The reality versus the fantasy?

Peirce: I feel incredibly lucky because I've heard all the same horror stories that you have, I'm sure. And I think in my mind, I think it's natural when you're kind of launching into any sort of new thing, and you're essentially ceding control of something that has always been kind of exclusively yours to other creative people. And so, of course, my biggest fear was, what if it looks lousy? And then my secondary fear was, well, what if it looks okay, but the stories stink? As a creative person, you're just protecting yourself. Like you said earlier, our egos are fragile enough. It's like, let's prepare ourselves for disappointment. So I’ve been so lucky because it has been beyond anything I could have imagined. I am delighted with my partnership with Nickelodeon. I think the writers are really sort of keyed in to what the things I love about the characters, and I think the animators and the art direction is just top of the line.

My kids are grown, so it's been a while since I sat down and watched cartoons in my life, but from what I have seen, I think that our show just looks amazing. I think it's setting a really high bar for animation on TV. And, hopefully, when people see it, they're going to see that, yeah, this is something special. And hopefully they can tell how much fun we're having making it, because it really has been positive.

Heintjes: Well, I only wish we had more time because I wanted to talk about Brad Gunter and Jack Black [who voices Gunter in the first episode] and food poisoning and vomiting and all those good things, but I know we’re short on time. So I just want to say congratulations on this achievement. It's been a pleasure talking to you. I've enjoyed your work for many years, and I'm really happy to see you expanding the Big Nate empire like this.

Peirce: Thank you so much, Tom. It's great to talk to you.