Slate has relationships with various online retailers. If you buy something through our links, Slate may earn an affiliate commission. We update links when possible, but note that deals can expire and all prices are subject to change. All prices were up to date at the time of publication.

On Oct. 22, 1889, a strange trial got underway in the town of Niles, Michigan. A woman, Almira Monroe, had accused her adult daughter Sarah Eliza Davis of larceny, specifically of having stolen a frying pan, some pewter plates, and a pair of infant stockings. The courtroom was packed as the trial began, abuzz with rumor and speculation, crowded with curious onlookers. But hardly anyone was interested in the charges of theft. Most people there believed that Davis and Monroe were concealing a much more sordid past. As the trial unfolded, the courtroom—and soon the nation—had become convinced that finally, after almost two decades, Ma and Kate Bender had at last been found.

The Bender family come straight from a Cormac McCarthy novel: They materialized seemingly out of nowhere, committed horrific and immeasurable acts of brutal violence, and then seemed to simply vanish. Nationally notorious, their deeds intertwined with the founding narratives of the American West—a place where Anglo settlers saw a future rich with possibility, with few strictures related to class, family background, or law to hinder them. Having plundered this land from its original inhabitants, the American government turned it over to thousands of poor immigrants who sought to make their names and fortune on stolen land. Some people found the American dream. Some people found poverty. And at least 11 people, probably more, found death at the hands of the Bender family.

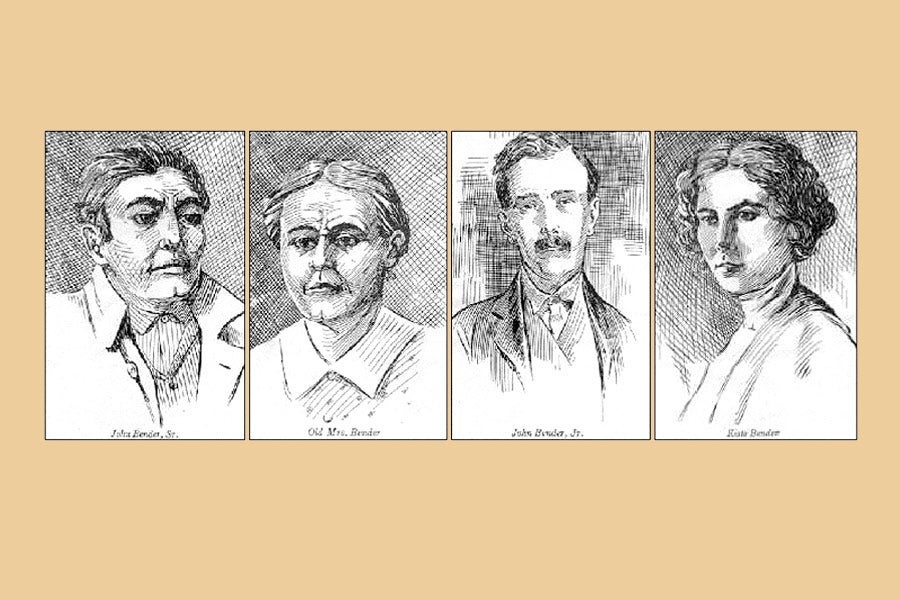

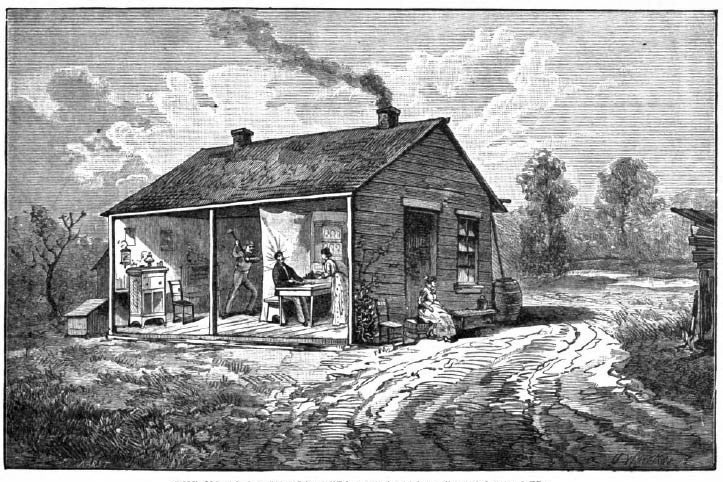

As expertly told in Susan Jonusas’ new book, Hell’s Half-Acre: The Untold Story of the Benders, a Serial Killer Family on the American Frontier, the saga of the Benders began in October of 1870, when two men who identified themselves as John Gebhardt and John Bender arrived in Osage Township, in the southeast corner of Kansas.* They seemed related, either through blood or marriage, though neither man ever elaborated on this. They divulged nothing of their past. The older man spoke very little and mostly in German; Gebhardt talked incessantly, making it clear that they were looking for a claim. (As per the Homestead Act, any federally surveyed plot of land was available to settlers willing to live on it and develop it; these plots were called “claims.”) The Benders built a small, one-room cabin along a creek in Labette County, the two men having been joined by John Bender’s wife, Ma Bender, and their daughter, Kate. For a few years their home operated as a waystation for travelers on this sparse, desolate stretch of land; in addition, Kate advertised herself as a spirit medium, offering services both as a spiritual healer, and as someone who could contact the dead. As was popular among some spiritualists of the day, Kate also professed a belief in free love.

As Jonusas tells it in her gripping true crime narrative, people began to disappear shortly after the Benders arrived, but at first no one thought too much of it. This was the frontier, after all. People died or vanished all the time, taken by the elements, lost in drowning mishaps, or simply walking away from their old lives to reinvent themselves. It was only after William York—brother of rising Kansas politician Alexander York—went missing in March of 1873 that suspicion fell upon the Benders. A search party led by Alexander York interviewed them at their cabin on April 4 of that year, finding them odd and hostile, but York wasn’t entirely ready to accuse them of having murdered his brother. (As they left, Kate offered her mediumship services to York to aid him in finding William.) That night, York and Leroy Dick, the township trustee, resolved to suggest that every cabin in the township be searched, to find out more about the Benders without drawing undue attention that they were under suspicion.

That same night, the Benders fled; by the time the authorities came back to their cabin, they found it abandoned, and pulling back a heavy canvas curtain that divided the room in two, they were overcome with the reeking stench of decay. Underneath the crawl space below the cabin, they found a mass of decomposing human remains; more bodies were discovered buried in the Benders’ orchard, and another, never-identified corpse was discovered in their well. In all, 11 bodies were recovered.

The murders were a media sensation, one of the first truly national serial killer stories to grip America’s consciousness. The Benders were active long before H.H. Holmes, Austin’s Servant Girl Annihilator, or Jack the Ripper in England; they were also, unusually, a family, not a lone individual, and Kate’s role as the public face of the clan added that much more mystery surrounding the killings. A beautiful, young woman advocating free love, after all, hardly fit the profile for a Western desperado, and the heady mix of sex and death Kate represented drove salacious media reports across the country.

What made the story even more unusual is the fact that, while they fled their cabin, the Benders didn’t exactly vanish. Eyewitnesses reported how they’d seen the fugitives escape by train—Ma and Pa to Missouri, and Kate and John to Texas. The latter were seen in Denison, Texas, before reuniting with the older couple in Red River Station. From there, the family moved further west into Indian Territory. There they settled down, known to locals who would regularly report on their whereabouts.

And yet, the Benders were never caught or even pursued, beyond a few half-hearted efforts. Surrounded, as they were, by criminals—including other murderers and thieves seeking refuge in land beyond the reach of federal or state law enforcement—arresting them would have meant sending in the army. And because state and local governments—along with private detectives and bounty hunters—all lacked the resolve or inclination to bring them to justice, the Benders were allowed to live virtually unmolested, despite the nationwide clamor for their capture.

Which is why the trial of Sarah Eliza Davis became such a sensation: It seemed an easy out. Half of the Bender clan, it seemed, had simply fallen into the lap of law enforcement; all they had to do was bring them back to Kansas. But at a preliminary trial to determine their identities, the mystery only deepened. Of the 16 witnesses brought to the stand to identify Ma and Kate Bender, seven were positive they were the Benders, seven were equally positive they weren’t, and the remaining two couldn’t come to a definitive conclusion. Eventually, their defense lawyers were able to prove that Davis and her mother, Almira Monroe, were definitely not the Benders; they were released, narrowly escaping an almost certain execution for crimes they did not commit. Meanwhile, the final fate of the actual Benders was never established. For years, rumors abounded that they’d been spotted, or that persons unknown had caught up to them and quietly exacted justice, but nothing definitive ever came to light.

Reading Hell’s Half-Acre, I was reminded again and again of what the American West seemed to promise to the white settlers that colonized it: a place where one could shed one’s identity and start anew, where one’s past had no bearing on one’s future, where everyone had an equal chance to make a fortune. It was a place that existed less as a geographic region than as a network of stories, the vast majority of which promised rebirth. Those stories brought to the West all manner of those seeking a new start. Some, like William Bonney, found fame through violence; others reinvented themselves as prosperous merchants and politicians. James Reavis remade himself as a baron and nearly stole the entire state of Arizona through fraudulent land grants. Out west, life was cheap, identity even cheaper, and justice was cheapest of all.

Beyond its gruesome details, the Bender story intersects with these stories while upending them. Despite their being household names, we still know almost nothing about the Benders, aside from the few brief years they were in Labette County. We don’t even know Gebhardt’s relationship to the others: Was he, as many assumed, Kate’s husband? Or her brother? Was he related at all? Did Kate truly believe she could speak to the dead, or was the entire thing just a ruse to dupe unsuspecting victims back to the cabin? Who was the real mastermind behind the murders—loquacious but unsettling Gebhardt, Ma or Pa, or Kate, the strangely enigmatic figure that predominates in popular imagination? How much of their motivation was greed, and how much of it bloodlust?

Never brought to justice or made to answer for or even explain their crimes, the Bender family left behind more questions than bodies. Their spectacle of violence puts the lie to the typical stories of the West, where colonization depended on some kind of redeeming narrative—something that made sense of the bloodshed and explained away the Native American genocide as part of some larger story of progress.

Laura Ingalls Wilder’s Little House on the Prairie books, for example, offered parables of self-reliance and resilience, portraying places like Kansas as a crucible where the pure in spirit would be hardened and find success. So it’s not surprising that Wilder—whose family lived for a time in Independence, Kansas, not far from the Bender cabin—would be among the many who tried to offer a satisfying conclusion to the Bender saga. The Benders never appear in Wilder’s books themselves, but at a Detroit book fair in 1937, she told an audience how, as a young child, she and her family had stopped at the Benders’ on their journey to their eventual home. “I saw Kate Bender standing in the doorway,” she recalled. “We did not go in because we could not afford to stop at a tavern.” After the bodies were discovered, Wilder continued, a neighbor came to the house and talked “earnestly” with her father, who took his rifle and told the family, “The vigilantes are called out.” He didn’t come back until morning, and in subsequent years, Wilder told the audience, whenever he was asked about the family, he would reply with “a strange tone of finality”: “They will never be found.”

As Jonusas notes, though, this story is almost surely untrue. Wilder’s daughter, Rose Wilder Lane, had sought to weave it into the family’s history, attempting to coax her mother into incorporating it into her works. While Wilder resisted writing about the Benders (deciding the material wasn’t appropriate for a children’s book), she wasn’t, in Jonusas’ words, “quite able to resist the lure of being associated with such a famous case.”

Not only that, Wilder must have at least felt some obligation to reel the Bender story back into the moral framework of her writing—suggesting that in the absence of formal law enforcement, at least vigilantes could uphold a basic morality on the plains. Such narratives have long endured—not just in the successful TV series based on Wilder’s books, but in more recent film and television, including Taylor Sheridan’s recently concluded prequel to Yellowstone, 1883.

Sheridan’s Western, as with so many other settler narratives, frames the protagonist’s maturation and self-discovery against a backdrop of lawlessness and violence, much of it originating with Native Americans. Narratives of yeoman farmers and rugged self-reliance depend on forgetting the Homestead Act’s state appropriation of Indigenous land, or the almost constant need for federal soldiers to enforce that appropriation. If there is violence and suffering, these stories tell us, at least it is not in vain, allowing young men to prove their mettle or families to finally achieve their dream of homeownership.

The true story of the Benders offers a perverse inversion of such satisfying morality tales: The Bender family, immigrants with nothing, made a life for themselves on the frontier, to be sure, but they achieved it not by violent confrontations with the people whose land they occupied, but with other settlers. The actual frontier, the Bender story tells us, was hardly a place of civilization vs. savagery, whites vs. barbarians, Christian values vs. superstition, or hard work vs. lawlessness. It was a war of all against all, with settler violence flung outward in a myriad of directions without purpose or reason, let alone morality. With their disturbing, unpunished crimes, the Benders end up revealing the lies that undergirded Manifest Destiny and the settler colonialism that made this nation, a hard truth as sickening as what their neighbors found buried beneath their cabin in 1873.

Correction, March 17, 2022: This piece originally misstated that the Osage Township where the Benders lived is in northwest Kansas. It is in southeast Kansas.