‘I’m Not Lamenting the Existence of Marvel’

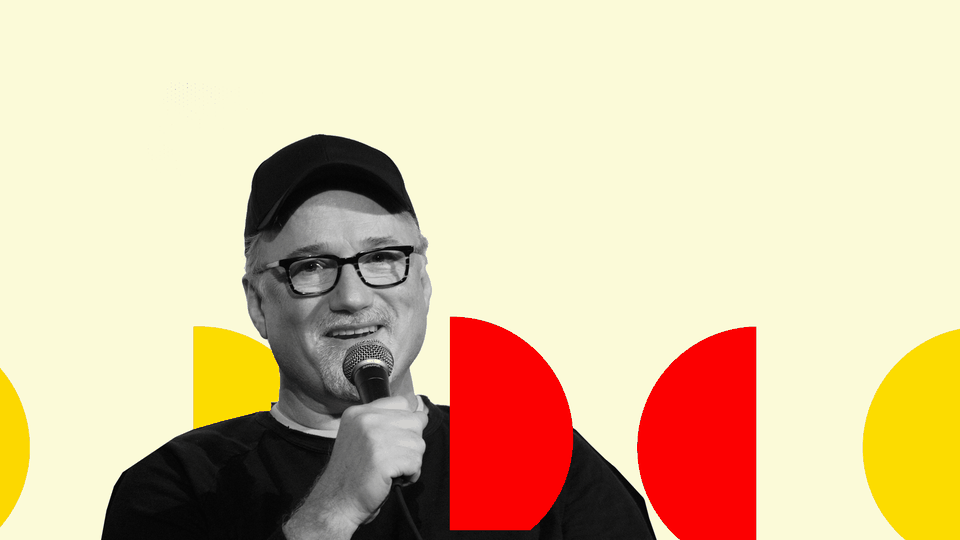

David Fincher spoke with The Atlantic about his new Netflix film, Mank, and his theory of moviemaking after 30 years in Hollywood.

David Fincher’s new film, Mank, begins with a title card announcing the arrival of one of cinema’s first real auteurs. “In 1940, at the tender age of 24, Orson Welles was lured to Hollywood by a struggling RKO Pictures with a contract befitting his formidable storytelling talents,” it reads. “He was given absolute creative autonomy, would suffer no oversight, and could make any movie, about any subject, with any collaborator he wished.” Then the score’s ominous piano notes kick in, as if Hollywood is greeting this proclamation of artistic control with dread.

Mank, however, isn’t about the famed director who went on to make Citizen Kane. It’s about a man who spent a short but pivotal time in Welles’s orbit: Herman J. Mankiewicz, the co-writer of Citizen Kane. A lowly scriptwriter might seem like a curious subject for Fincher, one of cinema’s best-known filmmakers, whose reputation for exacting attention to detail and on-set rigor is unmatched. And there’s a sweet sort of irony to the fact that this modern-day auteur’s first film about moviemaking spotlights a Hollywood gadfly who had to fight to be recognized for his contribution to a masterpiece. But in some ways, Fincher has been waiting almost 30 years to make Mank, which feels steeped in his observations of, and grievances with, the movie industry.

The genesis of Citizen Kane has long been a matter of furious debate among cinephiles, a proving ground for arguments about directorial auteurism versus greater collaboration. But that thread is of secondary importance to Mank, which debuts on Netflix today. “I was never interested in the idea of who wrote [Citizen Kane],” Fincher told me. “What interested me was, here’s a character who, like a billiard ball or pinball, sort of bounced around in this town that he, by all accounts, seemed to loathe, doing a job that he seemed to feel was beneath him. And then for one brief, shining moment, he stood his ground because—and I feel that this is entirely due to Welles—he was given an opportunity to do his best work.”

Mank, which was written by Fincher’s father, Jack (who died in 2003), is no celebration of Welles—the young director, played by Tom Burke, is a dynamic but wildly egotistical figure in the film, storming in near the end to thunder at Mankiewicz for demanding onscreen credit for Kane before angrily conceding. Nor is Fincher’s movie exactly a flattering portrait of Mankiewicz; Gary Oldman plays the protagonist as an undeniable wit who is given to excessive drinking, gambling, and fighting with every boss he has. But Mank does get at the weird, alchemical nature of storytelling in Hollywood—and how a decade of industry gripes, political grudges, and largely unacknowledged work nudged a world-weary screenwriter into helping create one of the greatest films of all time.

When it premiered in 1941, Citizen Kane was advertised to audiences as the singular creation of Welles, and yet without Mankiewicz, it likely wouldn’t exist in the form we know. The relationship between author and auteur fascinates Fincher; together, these two artists form the “chromosomal lineage of a film, because you need 23 chromosomes from the writer and 23 chromosomes from the director.” But he recognizes that films are the result of bigger collaborations: “The thing that makes a movie is very intimate conversations between actor and director, director of photography and director, director of photography and actor, camera operator and actor.”

Fincher is happy to puncture the concept of the omnipotent auteur while acknowledging that a director will always be at the nexus of every artistic choice being made on set. “The person standing in the middle of all these decisions, in some way, puts their fingerprint on everything. If you think that you can direct a movie and not in some way show your hand as to who you are, you’re nuts,” he said. The very act of directing, he added, requires stitching together new realities for the screen. “When you say, ‘Okay, I love her line on take four, but I love his response on take 16; I’m going to put those two things back to back.’ Now I’ve created a new thing that never happened.”

Hollywood has operated for decades off this strange, undefinable process, in which millions of creative decisions pass through a single person, for better or for worse. Mank takes an ant’s-eye-view of this system, following Mankiewicz through the corridors of power as he interacts with Welles, the studio moguls Louis B. Mayer and Irving Thalberg, and the media tycoon William Randolph Hearst (Charles Dance). The latter was a friend of Mankiewicz’s who became the chief inspiration for Citizen Kane’s outsize protagonist, Charles Foster Kane. To most of these honchos, Mankiewicz is somewhere between an amusement and an irritant, and for much of Mank’s running time that’s all he is—until he finally decides to fight for his stamp on Kane.

To Fincher, Mankiewicz’s cynicism about Hollywood is a defense mechanism; it’s a way for the writer to insulate himself from the creative frustrations of working within a monolithic business mostly to pay the bills. “I used to direct television commercials; I know what that is [like]. My dad used to write magazine stories for Sunset; he knew what that was [like],” Fincher said. Those personal experiences informed the father and son’s conversations about Mank, who went unacknowledged for many of his most famous Hollywood contributions, including the idea to have The Wizard of Oz play out partly in black-and-white and partly in color. In fact, Mank didn’t seem to care about credit until he fought for his name to be on Kane, for which he won an Oscar. “Credit is like the distilled version of importance,” Fincher said. “The [bigger notion of] importance is actually like a 10-pound bushel of amoebas ... It’s going to spill over the edges.” Credit, meanwhile, he said, simplifies that unwieldy concept into something more clean-cut, which is why it came to mean so much to Mankiewicz.

Mank has been on Fincher’s desk in some form since about 1992, when his father first presented him with an early draft of the screenplay that he had started as a retirement project. The original script, according to Fincher, was something of a “posthumous arbitration screed,” based largely on the film critic Pauline Kael’s infamous essay “Raising Kane,” a 50,000-word argument that claimed Mankiewicz was the primary author of Citizen Kane. Much of Kael’s article has since been disputed, so Jack Fincher’s later drafts brought in a plot about the political context of the time. A chunk of the film focuses on the socialist author Upton Sinclair’s doomed candidacy for governor of California, which was partly stymied by Hollywood’s promotion of his Republican rival, Frank Merriam.

That darker context gives the movie some tonal balance: For every moment of grandeur, there’s an acidic aside or a visual wink to the industry’s seedy underpinnings. I pointed out to David Fincher that an early establishing shot of a glitzy studio lot, with animals walking around and extras hanging out in costume, quickly cuts to a bathroom where executives are talking—where the actual business is being done. “That’s funny; I hadn’t thought of that. I’m gonna use that,” Fincher joked. For all the film’s critiques of Hollywood, Mank still hums with wonder at the creative playground the industry could be, even in its infancy. “My father liked highbrow things, but one of his favorite movies was [the comedy] Hearts of the West,” Fincher said. “So he had a little bit of a cheeseball idea of what Hollywood was about.” So, no, the establishing shot of the lot isn’t meant as a jab at cinema. “I chose that [location] because it gave me this beautiful vantage point of the Hollywoodland sign,” Fincher said.

Still, Fincher isn’t the sort of director to make a sincere, simplistic love letter to Hollywood, given his travails over the years—hence Mank’s concurrent sense of skepticism. Fincher’s debut film, the 1992 big-budget franchise sequel Alien 3, was taken away from him by the studio and recut; he disowned the final product. The kinds of stories he likes to tell—geared toward adults, not made on tentpole scales—have receded in the past decade. Many of his projects have fallen apart in recent years, and he hadn’t made a movie since 2014, despite a consistent record of box-office success (his last movie, Gone Girl, grossed $368 million worldwide on a $61 million budget). During his press tour for Mank, he swirled up controversy by referring to the 2019 film Joker as “a betrayal of the mentally ill” and criticizing the industry’s fixation on huge-budget releases over everything else.

Fincher isn’t naive about how Hollywood’s profit motives have shifted over the years. “I do not begrudge capitalism ... I do not begrudge a movie studio for wanting every at bat to lead to a home run. That seems entirely healthy to me, and I’m not lamenting the existence of Marvel. They have refined and defined a kind of predictably replicable joy stream for the people that love that stuff,” he said. “But there was a time and a place where the middle of this equation was thoughtfully protected, and fertilized, which is mid-range movies … My lamentation is that the middle has fallen out, and a lot of interesting things with it.”

Joker, Fincher acknowledges, was inexpensive compared with many other comic-book movies, but its franchise origins allowed the studio, Warner Bros., to present it as a blockbuster. “It may just be that because this movie exists under the aegis of a comic-book movie and a comic-book character, it gave people license to understand” the dark themes at work, he said. “I’m looking at it saying: It just gets harder to trot out your wares [as a director of mid-budget films]. It just gets harder to get people to take those kinds of risks.”

But, Fincher insists, he doesn’t have an ax to grind. Since the release of Gone Girl, his creative energies have mostly been channeled at Netflix, where he produced and directed two seasons of the procedural crime show Mindhunter before turning to Mank. “The fact that these kinds of [non-tentpole] opportunities have now moved to the streamers—it’s not a tectonic shift that is keeping me up at night,” he said. “I’m looking at it going, Well, you can’t find this kind of risk taking in these established venues that we all understood for years. Studios used to have portfolios; they would do something low-budget, something medium-budget … I’m wise enough to know that there’s a part of the immense profits of Home Alone that gave [Fox] the confidence to greenlight Fight Club.”

As major studios prioritize huge global grosses, Fincher sees the potential for would-be smaller-budget classics fading away. “I don’t know that The Godfather gets made in this day and age. I certainly know that The Exorcist never gets made again,” he said. “Chinatown is a movie that … you can’t put a price tag on today, in spite of everything. You can’t put a price tag on what it’s worth to Paramount. Look at the crater that that movie made. You can’t put a value on the culture that it inspired.” At the same time, he doesn’t think art is at odds with commercial appeal: “I don’t make movies in spite of the people paying for it; I make it in conjunction with them. My hope is that [any movie I make] is more valuable 10 years later, 15 years later than it was its first weekend.”

Fincher’s desire for timelessness is what drives his exacting style, and his reputation among actors for filming many takes in search of perfection. “My mother was a Lutheran who always said, ‘Whatever you do, do it right’ … And this was instilled in me from a very early age, and it is part of why I shoot 14 takes instead of six,” he said. As I talked with Fincher for more than double our allocated time, that overriding passion came through in his every answer, with essay-length responses to every query (“I know that I have a communication problem,” he said). More than 30 years into his career, he’s still in search of the best way to tell stories on film. “Movies are 100 years old. We have barely scratched the surface of the power of this medium. I honestly believe that.”

Mank is, of course, a portrait of an industry in its infancy, when playwrights and novelists such as Mankiewicz, Ben Hecht, Dorothy Parker, William Faulkner, and others came to Los Angeles in search of quick paychecks, not artistic freedom. So there is real magic in the birth of Citizen Kane, a masterwork that crept up on one of its creators, and that left a lasting crater, as Fincher put it, in our culture. That’s the tension at the heart of Mank—that even Hollywood’s most jaded writer could make the most meaningful contribution.