How The Eight-CDs-For-A-Penny Music Clubs Actually Worked

If you came of age in the pre-streaming era of the '90s, you remember having to buy your CDs from stores. Or, maybe you took advantage of the Columbia House music club and its eight-CDs-for-a-penny deal, a discount that was too good to be true. How could they sell products for next to nothing and still make a profit?

With a business model that’s downright Kafka-esque, music clubs managed to make money hand over fist by maintaining a low overhead, a high markup, and an ever-changing set of confusing rules. The following slice of music industry history lets you in on how music clubs made money, what customers were paying for, and how exactly they were being screwed.

Record Clubs Trapped Subscribers With Negative Option Billing

How Columbia House made money https://t.co/ydSuavynvj pic.twitter.com/7LuqHdUJkj

— Business Insider (@businessinsider) July 25, 2018The BMG and Columbia House record clubs used a method called "negative option billing." This means a customer signs up for a service, and a company mails them something - and bills them for it - once a week, month, or year, unless the customer objects.

A former Columbia House employee told The AV Club:

The whole business was premised on this concept called negative option. Which just sounds so creepy and draconian and weird, but the idea that if you don’t say no, we’re going to send you sh*t. It’s going to fill your mailbox, and we’re going to keep sending it unless you panic and beat us back. That was how the money was getting generated.

Negative option billing was outlawed in Ontario, Canada, in 2005. The Federal Trade Commission keeps a close eye on companies that use negative option billing, and insists that contract terms must be clearly stated.

Columbia And BMG Sold Records Through An Implied License

Columbia House kick-started so many of our record collections: https://t.co/RX0Oqx0Swc

— MeTV (@MeTV) January 2, 2018

Were you a member? pic.twitter.com/Z3YXl5yWZVYou'd think record companies would be excited about BMG and Columbia House selling tons of CDs to people across the company. Not so. BMG and Columbia House sold albums based on an "implied license." This is where a distributor pays a lesser fee for a product, and if the payment is accepted, it's assumed that a license to sell the product has been granted.

It wasn't until 2006 that record companies got actually written licenses from music clubs. Until then, BMG and Columbia House were buying products at low cost and then selling them at a huge markup. When record companies complained about the implied licenses, music clubs threatened to stop carrying their products.

It wasn't technically extortion, but it was definitely sketchy.

Music Clubs Printed Their Own Versions Of The Albums They Sold

BMG Music Club #AgeYourselfIn3Words pic.twitter.com/nC3zIYP2Pj

— Megan Westra (@mwestramke) June 7, 2018The most important aspect of the music club business was keeping costs low, especially when it came to their products. In many cases, record clubs acquired the master tapes of the albums they sold and pressed their own copies, meaning the record companies and artists didn't see any profits from the sales of these albums.

In the documentary The Target Shoots First, director Chris Wilcha takes a trip to the Columbia House production center in Terre Haute, IN. He finds a full-fledged CD pressing and printing facility, along with a group of local college students who spend their summer mailing out "free" CDs.

The User Agreements Changed Constantly

Cleaning out old stuff, getting ready to move. Do y'all remember the BMG music club? pic.twitter.com/74P8r7rLuz

— Ken Webster Jr (@ProducerKen) December 17, 2015One way music clubs made more money was by changing their user agreements without saying anything - or putting the changes in very small print. The basic user agreement said they would send you a CD, and if you didn't mail them within 10 days to let them know you didn't want the CD, you had to pay for it. The agreement changed at the apparent whim of the music clubs.

Music Clubs Purposefully Marketed To Rural Areas

Look what I found being used as a bookmark... an envelope from the BMG Music club... I checked. The website no longer exists. DANG! WHERE WILL I GET MUSIC FROM NOW?!?!?! pic.twitter.com/Hx4xwxUZlg

— Brian Bennett (@brian_o_bennett) March 15, 2018Most of Columbia House's marketing was directed towards Middle America and rural areas rather than metropolitan centers with dense concentrations of record stores. A former Columbia House employee explained:

I remember there was an understanding back then that a lot of the people receiving these catalogs were so… These were people in the middle of nowhere. That was part of the idea of it: you had to order music through the mail, because you had no access even to a record store.

Columbia House Employees Knew They Were Grifting Consumers

My Columbia House Music Club membership #90sTimeCapsuleItems pic.twitter.com/6mxeG4lyWZ

— Carrie (@spicypants) February 1, 2017The predatory practices of music clubs weren't lost on employees who made their bones charging unsuspecting customers for albums they didn't want. A source who worked for Columbia House told Forbes, "You could criticize us for not bringing more attention to the fine print, but it was all there."

Another former employee called their business practices "brilliant" and "perverse."

Music Clubs Banked On Reselling Collections

When I was #In3rdGrade Columbia House Music Club was that stuff. 12 tapes for the price of 1? What,lol?! #oldschool pic.twitter.com/9gDiv98G

— Such_a_Lady215 (@Such_a_Lady215) November 13, 2012Every time a new format came along (cassettes, CDs, etc.), companies like Columbia House used the occasion as an excuse to sell customers something they already owned. Even though music clubs claimed to introduce subscribers to new music, they made their real money reselling entire collections to music lovers who wanted to update their libraries to a new format. For instance, if you had every Black Sabbath album on vinyl and cassette, why not have it on CD, too?

In Chris Wilcha's first-hand account of working at Columbia House, The Target Shoots First, he notes, "Consumers used Columbia House as a fast way to replace their vinyl with CDs. They bought everything they already owned for double, even triple the price."

Columbia House Introduced A Generation Of Young People To Mail Fraud

Mail-order music club Columbia House is no more: http://t.co/nmF1KtiEON pic.twitter.com/yhn8iaiKA2

— FACT (@FACTmag) August 11, 2015In 2015, Jack Hamilton wrote an article for Slate detailing his first foray into crime after joining the Columbia House record club when he was 13 years old. His article details how he ordered albums, never paid for them, and never canceled his account - thus falling into the music club trap.

He, like a lot of young people who ordered albums through music clubs, was technically on the hook for fraud, but Columbia House and BMG had bigger fish to fry - and they weren't going to take a teenager to trial.

My father got on the phone with the club and talked them down from some of the more outrageous penalties, basically telling them that, while I’d certainly messed up, 13-year-olds can’t actually sign contracts, and that it was shady business on their end that they had nothing in place to preclude this from happening. (He’s a lawyer.) I paid what I’d originally "agreed" to owe, and they terminated my membership.

Fraud Was Rampant During The Music Club Era

The @ottawabluesfest -RHCP, Duran Duran, Nelly, The Cult. My Columbia House music club order! Can't wait! pic.twitter.com/TLeXVYEG8B

— Tim Tierney (@TimTierney) February 23, 2016Fraud on a major scale was a huge problem with Columbia House and BMG. People signed up with different names and credit card numbers in order to get heaps upon heaps of free CDs, cheating the music clubs out of thousands of dollars. In 2000, 60-year-old Joseph Parvin plead guilty to fraud after ordering 26,554 CDs through 2,417 different accounts between 1993 and 1998.

Parvin wasn't the only one to pull a scam like this. 33-year-old David Russo devised a similar scheme. He ordered more than 22,000 CDs that he didn't pay for, and flipped them at flea markets.

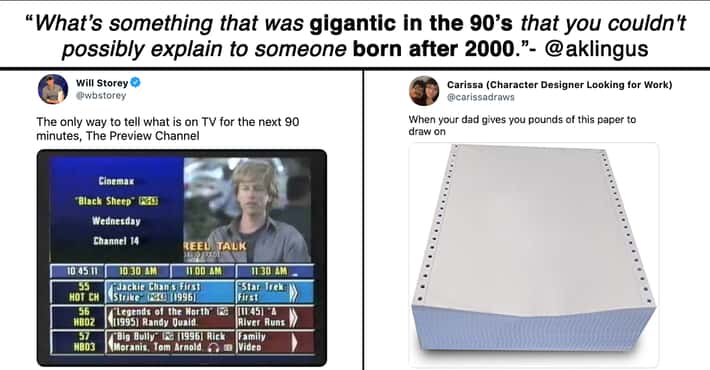

Music Clubs Weren't Sure How To Market To Young People

End Of An Era: With no one buying records, tapes or CDs, Columbia House has filed for bankruptcy pic.twitter.com/OQy52U6owG

— Darren Rovell (@darrenrovell) August 11, 2015After sales leveled off in the '90s, music clubs like Columbia House were confused on how to bring in new customers, specifically those from Generation X.

In the documentary The Target Shoots First, Chris Wilcha details the company's incoherent grabs at relevance as they discuss whether or not heavy metal is its own genre, or if Bad Brains are a rap group or "a real rock band."

Music Clubs Boosted Hootie & The Blowfish Album Sales

Today in 1994, Hootie & the Blowfish released Cracked Rear View. It's their debut album, and it took off at the beginning of 1995, and it's still the best-selling album in the history of Atlantic Records. pic.twitter.com/EZLY0wgQhi

— Eric Alper (@ThatEricAlper) July 5, 2018In the mid '90s, major label artists were selling millions of records. Alternative rock band Hootie & the Blowfish sold 13 million copies of their debut album Cracked Rear View, and 3 million of those sales came through Columbia House or BMG. In fact, in 1994, an estimated 15 percent of all CDs in the US were sold through a music club.

While this might sound like a great way for artists to make extra money, they didn't actually see royalties from music club sales. However, those sales were counted for RIAA certification, meaning that music club distribution could help an album go gold or platinum.

Music Clubs May Have Helped Peer-To-Peer Networks Become A Thing

On The Cutting Edge, BMG Music Club, 1991

— Robb Skidmore (@robbskidmore) March 24, 2016

...Pixies...Bob Mould... Replacements... Smithereens...The Sundays pic.twitter.com/ae2dwjHUCKPeer-to-peer networks like Napster and LimeWire are often touted as the death knells of the physical album market, but the availability of inexpensive CDs inadvertently helped bring the record industry to its knees. A former Columbia House employee said:

All of a sudden, by thinking, "Sh*tty format, we’re going to mark it up 180 percent, and everybody’s going to buy them." Well, yeah, they did, and they ripped them and decided to share those files. The thing about that CD format that I still find to be hilarious is it’s, like, they basically gave the bullets for the people to shoot them down once a new platform came along.

In an essay about the end of music clubs, Gizmodo writer Adam Clark Estes backed up this theory. He claimed, "In its first two years of operation, I spent countless hours on Napster, uploading my scammed tracks from Columbia House and downloading whatever I wanted."

Music Clubs Made A Ton Of Money

Owner of Columbia House music and movie club files for bankruptcy http://t.co/4FnXYLRX6R pic.twitter.com/8hjHk0yTzp

— TNW (@TheNextWeb) August 11, 2015At their mid-1990s peak, Columbia House and BMG made a lot of money. According to The Recording Industry by Geoffrey P. Hull, music clubs paid between $1.50 and $5.50 for a CD, which they then sold for $16. He reports that if the clubs sold one out of every three discs, they'd make close to $8 in profit.

Selling a low-cost product at a high markup is how Columbia House and BMG were each able to bring in $1.5 billion annually. A source close to the music club world told Forbes, "We were minting money."

Music Clubs Stayed In Operation Until 2009

"Tin Machine" holds its own between "Beaches" & "Electric Youth" in summer 1989 BMG music service club ad pic.twitter.com/EUooc6nTZp

— Bowiesongs (@bowiesongs) July 24, 2017Even though the offer of eight CDs for a penny is anachronistic, the merged iteration of Columbia House and BMG was in operation until June 30, 2009. The model changed considerably after the introduction of Napster, and the company began selling DVDs the same way it sold CDs.

In 2015, Columbia House made a comeback and began selling vinyl after John Lippman revived the company. The new owner said that he saw a rising interest in the "new format."