May 8, 2024

MODU Creates Architecture at the Threshold

MODU is trying to project hope through projects such as a nature conservatory in Jackson Hole, Wyoming, that is a net-zero-energy building that allows for semi-exterior rooms for connections to nature, or a mixed-use office and retail development in Houston with self-cooling walls. “In terms of the environment, there’s the feeling of helplessness,” says Rotem. “It can feel crippling. We are also teachers, and I feel that desperation.” Rotem is on the faculty at Columbia University and is also an associate professor of practice at Ohio State University, where Hoang is head of architecture. “The book proposes optimism that as a community you can design microclimates, with mini projects, and you can affect your 15-minute commute, and it is meaningful.”

One way that Hoang and Rotem are trying to convey this optimism is with their evocative drawings, which transmute data to evoke emotion. “When you have an emotional engagement, you have a reaction,” says Rotem. “That’s the problem with the mega issue of climate change. We’ve been warned for 50 years by scientists who are screaming at us, and we’re not able to understand the abstraction of 1.5 degrees.” Traditional architecture drawings depicting building structures or systems are limiting, adds Hoang.

In one such data project, Horizontal City, MODU’s team surveyed 12 neighborhoods across the five boroughs. The architects were inspired by people’s instinctual movements throughout the city—that we cross to the sunny side of the street on a cold winter day or stay in the shadows of tall buildings on a hot one. “How do we draw the experience of the microclimates of the city?” asks Hoang. On Fridays the staff would scout their chosen neighborhoods and then reconvene in Chinatown for dim sum to compare notes.

The resulting maps—of a chunk of blocks in Brooklyn Heights, the Financial District, or Eastchester Gardens in the Bronx, for example—are devoid of buildings’ exterior walls and instead depict the shadows they cast, as well as shade from trees, bus stops, outdoor dining sheds, and ephemeral happenings, such as protests. Parks and open streets were also included. After their analysis, the inequalities became clear: More affluent areas had more shade, creating more physical comfort and better air quality; lower-income neighborhoods can have surface temperatures as much as 30 degrees hotter than higher-income neighborhoods. “Shade should be accessible to everyone as a public right and it often is not,” says Hoang.

Another of MODU’s drawings appears to be a kind of aerial map in which tiny pixels aggregate in both dense and sparse patches. In fact the pixels represent shade cast by recycled plastic balls suspended on the fabric mesh roof of an aluminum pavilion outside the Design Museum Holon, near Tel Aviv. The “Cloud Seeding” pavilion transformed an uninhabitably hot public plaza into a site for public programming, rest, and relaxation. Mediterranean breezes kept the balls in perpetual motion, creating shade below; the open-air structure allowed daylight and air to enter freely. “What is important to us is that we are interdisciplinary but we also work within our discipline. Certainly we are always for planting more trees, but buildings need to do more. It’s buildings that contribute 40 percent of the carbon emissions in the world,” says Hoang.

One way that buildings can mediate their impact on the environment is by addressing microclimates, say Rotem and Hoang. “Microclimates are important at the building scale. Can you actually extend the seasons in spring and fall, expand the use, create more tolerance for breeze, for passive movements?” asks Rotem. “It also goes to psychology. Can you change habits, but in a curated way?” For Mini Tower One in Brooklyn, the architects experimented with microclimates outdoors, at the domestic scale indoors, and in between spaces.

An addition on the rear of a multifamily residential building allowed Hoang and Rotem to play with what they call “outdoor interiors.” The terraces and other transitional spaces could be fully enclosed in extreme heat or cold conditions but are meant to extend indoor-outdoor living through more of the year with radiant outdoor heating, drainage, and a roof fan, among other strategies. This interpretation of a passive house—an airtight envelope that, seemingly in contradiction, includes large openings—also creates a buffer zone where air is cooled or heated before entering the interior, using less energy. In Field Guide, Hoang and Rotem map the lots in Queens and Brooklyn that have additional buildable areas in rear yards with vertical opportunity: Imagine a city of Mini Towers.

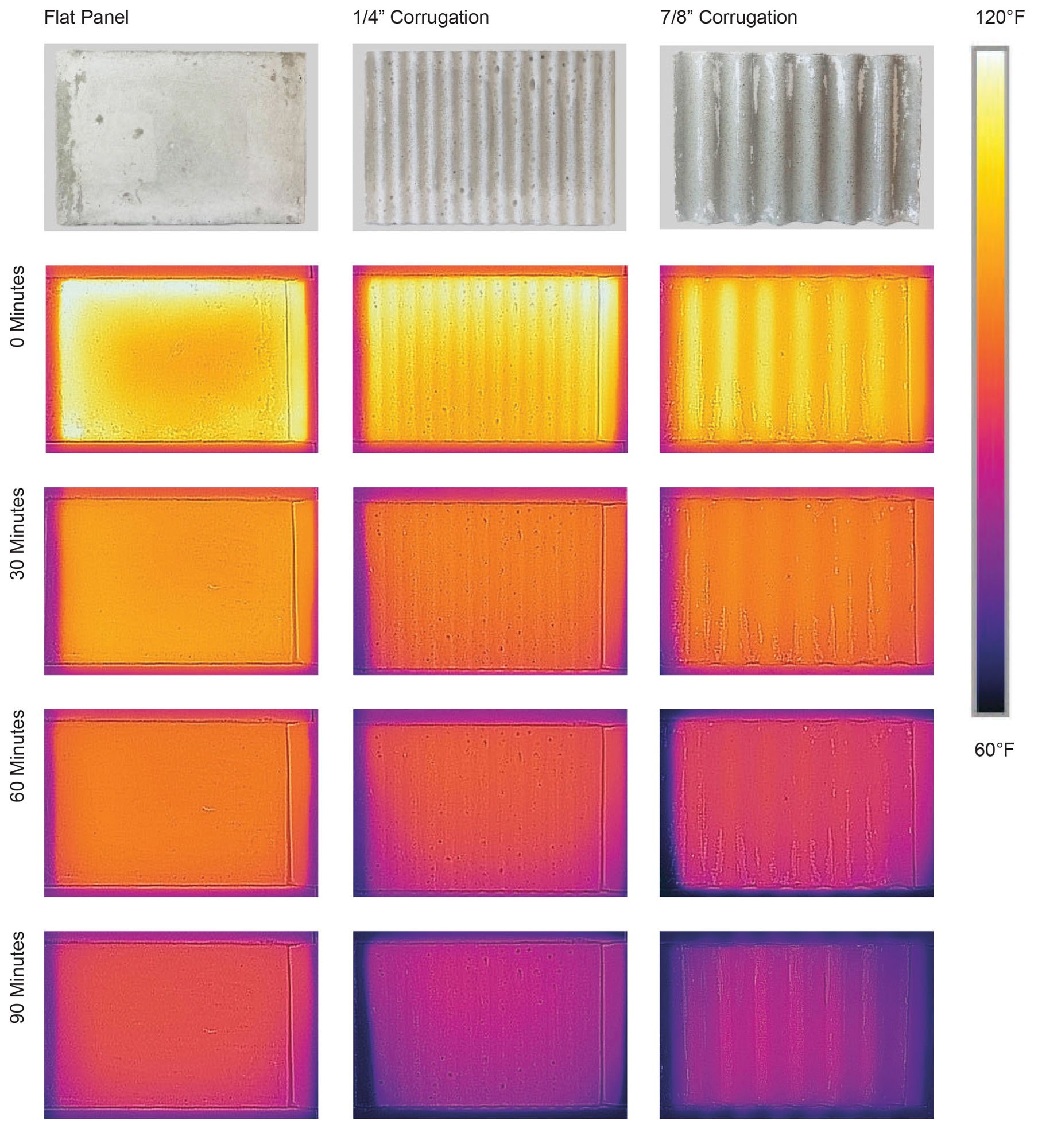

The architects embedded their thinking about microclimates in the facade at Promenade, a spec office building in Houston. Along with recessed walls and vertical fins, MODU conceived of corrugated concrete tilt-up walls, testing small slabs in a kitchen oven. The resulting textured surface disperses heat more quickly, creating cooler places where the architects could include pocket gardens and benches, even though Houston reached 110 degrees Fahrenheit last summer.

Some of these strategies were further developed during Rotem and Hoang’s time as Rome Prize recipients in 2017; others were refined through conversations they had in 2018— during two record-breaking heat waves—with some of Japan’s most celebrated architects, such as Go Hasegawa and Fumihiko Maki, supported by a U.S.-Japan Creative Artists fellowship from the National Endowment for the Arts. Field Guide is loosely structured by these geographical borders. But the point, say the architects, is that “you can start to migrate solutions from one place to another.”

Would you like to comment on this article? Send your thoughts to: [email protected]

Latest

Products

Poltrona Frau Reinterprets Gio Ponti’s Armchair

Dezza is reissued in a refined new edition with woolen satin Redevance upholstery fabric.

Products

What Not to Miss at ICFF 2024

During this year’s NYCxDESIGN festival, the International Contemporary Furniture Fair brings the most innovative design to Manhattan’s Javits Center from May 19 to the 21.

Products

These 3D Printed Luminaires Expand on Design Without Compromising Health

Cooper Lighting Solutions’ Shaper PrentaLux line offers sustainable options in a range of pendant styles, colors, and textures.