Johnny Otis, Anti-Racist R&B Pioneer

The legend who died last week at 90 obliterated the notion of "white music" versus "black music."

In a 1969 interview, Jimi Hendrix voiced a frustrated defense of his artistic ambitions and position as an African-American star in an increasingly white world of rock music. "What I don't like is this business of trying to classify people," he said. "Leave us alone… It's like shooting at a flying saucer as it tries to land without giving the occupants a chance to identify themselves."

It's a funny and beautifully perfect analogy, one that acknowledges the extraterrestrial implications of great art while highlighting the violence of categorization, the destructive confinement that comes from talking rigidly about "white music" versus "black music," which is really just another way of talking about "white people" versus "black people." It's fun to imagine Hendrix, aboard his own flying saucer, gazing down upon American culture's mess of racial anxiety and waving his hands dismissively: All this is bullshit.

I thought of this last week upon learning of the death of the great R&B pioneer Johnny Otis, a man devoted to calling bullshit on the stories we tell ourselves about race and music, and who made the world a better place to shake our asses in the process. Over a 90-year life and seven-decade career he carved an existence akin to what might result if Mark Twain and James Baldwin ever collaborated on a superhero comic, a story that makes you shake your head and mutter "only in America" and actually mean it in a good way.

His deeds were astounding in scope: He sang hit records, played on hit records, wrote and produced hit records, and helped break the careers of artists like Hank Ballard, Jackie Wilson, and Etta James (who inducted Otis into the Rock and Roll Hall of Fame in 1994, and sadly passed away only three days after him). He lived through Bird and Trane, through Brown v. Board and Barack Obama, through Kind of Blue and Sgt. Pepper and Watch the Throne. He hosted radio shows, ran for office, founded a church, wrote four books, and inspired a fabulous biography by a renowned historian. And through it all he played R&B music.

The fact that he was a white man always seemed to matter little, least of all to Johnny Otis. He was born Ioannis Alexandres Veliotes in California in 1921, the son of Greek immigrants, and from early childhood he loved African American culture with religious ferocity. He happily found that it loved him back. In 1941, in violation of California's miscegenation laws, he married a pretty young woman named Phyllis Walker; they had four children together and were married for 70 years. Otis's musical popularity in the black community was so great that in 1951 his head-shot—funnily and fittingly—graced the cover of a magazine called Negro Achievements. He had a decades-long friendship with Malcolm X, dating back to Malcolm Little's "Detroit Red" hustler days, and in his 1993 autobiography Otis referred to him as his "role model." Most importantly, he spent the entirety of his life railing loudly and tirelessly against racial injustice, long before such things were fashionable and long after they stopped being so.

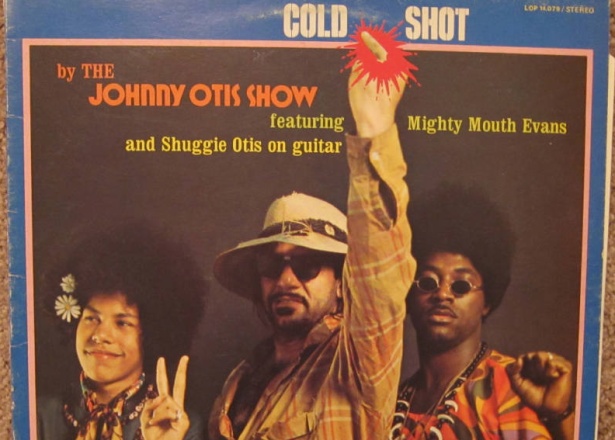

Johnny Otis was fond of referring to himself as "black by persuasion," and I'm not sure there's ever been a more wonderful self-description for a man with such a boundless love of culture—that's culture, period—or a more pithy indication of a complete and total anti-racist worldview. He was blessed with considerable musical talent, though his abilities paled next to his freakishly gifted son, Shuggie Otis ("Shuggie" being short for "Sugar," itself a nickname for "John," and yes, the fact that Johnny Otis named his son after himself but opted to call him "Shuggie" speaks generously to his parental character). He also had a world-class ear for the key of defiance: One of the great images of 1960s music is the cover to his 1968 album Cold Shot!, in which Otis is flanked on either side by a teenaged Shuggie and singer Mighty Mouth Evans, the former flashing a peace sign, the latter a Black Power salute. In between them stands Johnny, arm raised high, middle finger extended.

He had a massive and diverse catalogue—the luscious, faux-Ellington Harlem Nocturne," the uptown-cum-downhome "Barrelhouse Blues," the magisterially NSFW "Signifyin' Monkey"—but his most well-known record remains 1958's stone-cold classic "Willie and the Hand Jive," an irresistible piece of musical nonsense that's so great it feels almost primordial. It snatches the 3/2 clave rhythm known informally as the "Bo Diddley beat" and grooves like hell, goosed along by handclaps, a leering lead-guitar part, and an out-of-nowhere shout-out to Hoagie Carmichael's oddball standard "Doctor, Lawyer, Indian Chief." Johnny Otis sings the daylights out of it, too, a small masterpiece of hip, melismatic swagger.

I don't remember the first time I heard "Willie and the Hand Jive"—even on first listen, you can't remember not knowing it—but I distinctly recall the first time I learned, with shock, that the voice on the record belonged to a white man. It was one of those moments when a great curtain of cultural wrongness suddenly falls away, the instantaneous "that's the blackest-sounding white guy I've ever heard!" response slowly replaced by the realization that concepts like "blackest-sounding white guy" (or "whitest-sounding black guy") only make sense through a series of assumptions that are superstitiously close-minded, and racist in the very definition of the word.

MORE ON MUSIC

Johnny Otis saw American racial logic for the tortuous thicket of stupidity that it is and decided he wanted none of it. That he did this in the 1940s and 1950s, before it was the hip thing for white folks to talk loudly about how race doesn't matter, is staggering. When Otis hit the pop charts with "Hand Jive," suddenly attracting the very white kids he'd never been all that interested in, rock and roll was still a lean and hungry menace, a gathering revolution on the make, all grinding hips and gnashing teeth. "Help Save the Youth of America – DON'T BUY NEGRO RECORDS," read the infamous flyer circulated by White Citizens' Councils; here was a white man who wasn't just buying Negro records, he was making them. The great white-supremacist fear of rock and roll music wasn't that a generation of kids would grow up to be Chuck Berry—it was that that they'd grow up to be Johnny Otis, staring down their own whiteness, noisily sending it back to the worthless factory from whence it came.

Johnny Otis didn't singlehandedly change the world, but he made it a safer place in which to be Jimi Hendrix, Keith Richards, Prince, Adele, and anyone else who ever made music they love in the face of those who would have had them make something else. He'll never find his way onto a postage stamp and his name will soon fade back into the recesses of connoisseurship, but let it be known here that Johnny Otis was an after-hours American visionary, "black by persuasion," a hero to people who do things that matter. The best thing to be said about Johnny Otis isn't just that he played and loved R&B music as though doing so was a profoundly ethical act—it's that he was absolutely right that it was.