The Real Roots of Southern Cuisine

An interview with Atlanta Chef Todd Richards by Beth McKibben.

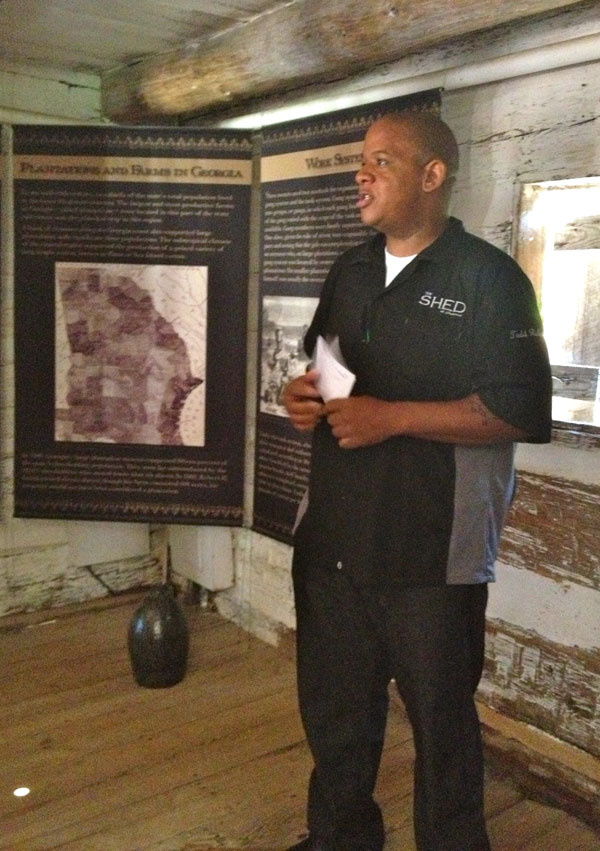

I recently sat down with Chef Todd Richards of The Shed at Glenwood in Atlanta to continue our discussion on Southern food and slavery. (Read part one here.) His talk inside the slave cabin at the Atlanta History Center’s Folklife Festival in September was not only filled with little known facts about slaves and their food, but gave all in attendance a glimpse into the real roots of Southern cuisine. And guess what? It ain’t all fried chicken and gravy laden biscuits. In fact, true Southern food is neither fatty nor simple. It’s clean, complex and, most importantly, born from the economics of survival.

I recently sat down with Chef Todd Richards of The Shed at Glenwood in Atlanta to continue our discussion on Southern food and slavery. (Read part one here.) His talk inside the slave cabin at the Atlanta History Center’s Folklife Festival in September was not only filled with little known facts about slaves and their food, but gave all in attendance a glimpse into the real roots of Southern cuisine. And guess what? It ain’t all fried chicken and gravy laden biscuits. In fact, true Southern food is neither fatty nor simple. It’s clean, complex and, most importantly, born from the economics of survival.

With the resurgence in all things Southern, our food is at the forefront. Restaurants around the country try and often fail at presenting truly authentic Southern cuisine. They doll it up with gravies, hot sauces and fry everything that isn’t nailed down in the kitchen. Then, they slap it on a plate and call it “Southern.” For Chef Richards, Southern is more than its Cracker Barrel image, with slavery at the very root of its beginnings. To know its history is to understand Southern food.

BM: Tell me why you’re so interested in food history and how it inspires you to create your dishes?

TR: My family did a lot of reading and a lot of cooking when I was growing up. The two are synonymous to me. In constructing a menu item, you have to have a direction, an understanding of the item you’re preparing. Where it came from, what kind of soil it grew in. That’s how dishes start to make sense. Take deer, for instance. Deer eat berries and acorns, so it’s no secret that venison tastes best when prepared with berries, nuts, etc. because that’s the diet of the animal. When you know how your food is grown, you understand how to achieve the greatest flavor by utilizing the elements of its creation, the methods by which it was originally prepared.

BM: Why is there such a resurgence in Southern food, and why is it happening now?

TR: People today are more concerned than ever about where their food is grown, that it’s grown in a good manner. When you have excess – excess money, excess food – you don’t worry about what you’re spending necessarily. But when you don’t have those things, which is the case for many people now, you worry about how your money is being spent and that it’s being spent on the right things. Also, I think Southern food is comforting. It bridges gaps not only economically, but socially. During tough times, you rely on two things: church and food. And in the South, those two things are synonymous. So I think when you look at the state of our economy right now and the strife we are facing, Southern food just makes sense.

BM: So you believe the country is reverting back to more straightforward, simpler foods?

TR: Southern food is really not that simple. It is an essential American storyteller along with our government and music. It has a long history. Southern food encompasses many regions, people and economics. It’s good, healing food born from strife and survival. The slaves weren’t creating Southern cuisine in order to make history, they were cooking to stay alive.

TR: Southern food is really not that simple. It is an essential American storyteller along with our government and music. It has a long history. Southern food encompasses many regions, people and economics. It’s good, healing food born from strife and survival. The slaves weren’t creating Southern cuisine in order to make history, they were cooking to stay alive.

BM: How did the slaves influence Southern cooking? What were the typical ingredients they were working with at the time?

TR: You have to look at two things: what came with the slaves on the boat and what they had to work with when they got to America. There was a strong Native American influence in the early beginnings of Southern food when slaves began arriving: crops like corn and techniques like frying. Then, you have crops and techniques that came over from West Africa with the slaves, like the peanut (or goober peas), okra (or gumbo) and stewing techniques. There’s also daily survival ingredients like watermelons, which served as canteens in the fields. It’s 95 percent water. The slaves also used the rind as soles for their shoes. So ingredients like this that are now part of Americana and the Native American influence really started shaping Southern food very early on. But you can’t discount other influences like that of the Spanish and Portuguese through Louisiana or the Latin influence through parts of Texas. The slaves worked with what was available to them and adapted their daily diets accordingly.

BM: So, through a diet based on survival, the slaves really transformed Southern foodways into what we see today?

TR: What people don’t really understand about Southern food is that it is all based off of preservation methods. How can we keep the food for the longest period of time and make sure it’s safe to eat? Africans never ate beef until it was introduced to them in America. Fish, vegetables, fruits were the diets of most African people. Salting and frying meats and vegetables were simply preservation methods they learned from the Native Americans. They adapted to survive, while in the process, unknowingly transforming the Southern diet with the ingredients they brought with them from Africa. They found that they could grow these crops quite well here in the South.

TR: What people don’t really understand about Southern food is that it is all based off of preservation methods. How can we keep the food for the longest period of time and make sure it’s safe to eat? Africans never ate beef until it was introduced to them in America. Fish, vegetables, fruits were the diets of most African people. Salting and frying meats and vegetables were simply preservation methods they learned from the Native Americans. They adapted to survive, while in the process, unknowingly transforming the Southern diet with the ingredients they brought with them from Africa. They found that they could grow these crops quite well here in the South.

BM: We know slaves were cooking these meals for themselves but do you believe the slaves began to cook using their native ingredients for their masters, or do you believe that began to occur during Reconstruction?

TR: Yeah, they were definitely cooking these meals for their masters. I mean, the thing about Southern food, when it’s cooking, it smells good! I’m sure they brought the best cook up to the house and left the more undesirable portions for themselves.

BM: What Southern cooking technique that survives today can be traced back to the slaves?

TR: Definitely one-pot cooking. Gumbo, cornbread and hoecakes were being done out in the fields. There were no lunch breaks. But, to me, the most essential technique to come out of slave-based cooking is preservation. How the food was preserved is what made it taste so good. But they weren’t thinking about that at the time. The economics of survival was the slaves’ only motivation. Preservation methods are truly what transformed Southern cooking to what we know it to be today.

BM: How did preservation methods influence the flavors?

TR: To me, greens tell the unique story of Southern food. There was no refrigeration, so slaves used meat, mostly pork, and salt to preserve the greens by laying the meat on top. Not only did the pork preserve what was underneath, but it flavored it as well. They didn’t necessarily eat the meat after the greens were finished. They might repurpose it. Frying was another technique. Many people are shocked to learn that fried chicken is not Southern-born but actually Scandinavian and Native American. Animals in West Africa were not fatty. It was hot; they didn’t require fat to stay warm. Frying was a preservation method the slaves adopted.

I found this out when I was up in Louisville, Kentucky, researching Native American foods. They were teaching the method to the Lewis and Clark Expedition. It was meant to preserve the meat underneath the skin during long journeys. They would fry rabbits, squirrels, small game birds in bear oil. Slaves in certain regions of the South caught on to this method, finding the skin of the chicken, for instance, to be quite tasty. Jerky is another example of preservation turned tasty snack in the fields. You take the meat off the bottom of the shank, slice it very thin and dry it out on tobacco leaves. They learned this preservation method from the Native Americans, because in the early days of slavery, Africans knew little of preserving meat. The slaves economically had no choice but to stretch every last morsel of food they had. Food preservation is the key to all Southern cooking. It is the essential ingredient.

BM: In hearing you speak at Atlanta Food and Wine in May, you talked about the misconceptions of soul food. What are those misconceptions?

TR: Soul food is tricky. It’s a category African American chefs get placed into not by choice. That term wasn’t coined until the early 1960s and implies that our contribution to food, most importantly Southern food, has only occurred over the last 45 years. Most African American chefs don’t embrace that term. It’s not the full story. If you ask me if I put my soul into my food, yes, I do, but you could ask Guy Wong from Miso Izakaya and he would tell you the same thing. ‘Soul food’ has a long lineage. The African American contribution to Southern food doesn’t start in the sixties, but is deeply rooted in its beginnings.

TR: Soul food is tricky. It’s a category African American chefs get placed into not by choice. That term wasn’t coined until the early 1960s and implies that our contribution to food, most importantly Southern food, has only occurred over the last 45 years. Most African American chefs don’t embrace that term. It’s not the full story. If you ask me if I put my soul into my food, yes, I do, but you could ask Guy Wong from Miso Izakaya and he would tell you the same thing. ‘Soul food’ has a long lineage. The African American contribution to Southern food doesn’t start in the sixties, but is deeply rooted in its beginnings.

BM: Do you think people began to eat specific foods in the sixties, and that’s why the term was coined?

TR: No, people have been eating it all along, but African Americans just didn’t get any credit for it until then. Like now, the sixties were a turbulent time in America. People were seeking comfort. Slavery also destroyed families. The only thing that remained the same was the dinner table. Your fellow slaves sometimes became your family. A meal brought comfort to the slaves, not so much as nourishment but by keeping the family together.

BM: What do you want people to know about slaves and Southern food?

TR: Southern cuisine is regional and really can’t be categorized under a big umbrella. Key ingredients like greens and preservation methods are the great equalizers in our story but, after that, it’s all regional.

Georgia and Alabama Southern is totally different from Appalachia Southern. Frying is more prevalent in the colder climates of the South than in the Deep South. They have more animals with fat on them whereas in Georgia, for instance, it’s warmer and so our native animals are leaner. Where would the slaves have gotten the oil to fry the chickens? They didn’t reach for a bottle of peanut oil like we do now. Those influences came into the picture much later. There are more cornbread recipes in Georgia and Alabama than in the Carolinas, where rice is more prevalent. In Appalachia, stews are more common. The slaves knew how to preserve and cook with what nature had to offer. Each region had its own micro-climate and trade routes. The food of the South is as diverse as its people.

Georgia and Alabama Southern is totally different from Appalachia Southern. Frying is more prevalent in the colder climates of the South than in the Deep South. They have more animals with fat on them whereas in Georgia, for instance, it’s warmer and so our native animals are leaner. Where would the slaves have gotten the oil to fry the chickens? They didn’t reach for a bottle of peanut oil like we do now. Those influences came into the picture much later. There are more cornbread recipes in Georgia and Alabama than in the Carolinas, where rice is more prevalent. In Appalachia, stews are more common. The slaves knew how to preserve and cook with what nature had to offer. Each region had its own micro-climate and trade routes. The food of the South is as diverse as its people.

BM: Do you believe that your slave ancestry has influenced your cooking? Any special family recipes that were passed down?

TR: I don’t really have any family recipes that were written down, but I do know how my family constructed meals. My grandmother and great-grandparents were fantastic cooks. Family meals were big when I was growing up. They were like celebrations. We had barbecue every summer, prepared by my Dad. Everything revolved around food, even the gifts we gave to one another. But there were two different Southern influences in the family. I can’t tell you exactly where each side comes from in the South, but I can tell you the region by the way they cook. My Mom’s side is more Appalachia/Carolinas/Ohio with stews, rice and frying. Whereas my Dad’s side uses smoking methods and vinegars when cooking, like in the mid-South. I can tell my family’s story through food. So essentially, my Dad’s more cornbread, my Mom’s more biscuits.

I’ve never really thought about this before, but I just discovered my family tree through what I do every day: food. This is my family tree.

Chef Todd Richards’ Greens

Bunch of seasonal greens

Bunch of seasonal greens

Cider vinegar to taste

Smoked meat, such as turkey

Crushed red pepper flakes

Sorghum (optional)

In a heavy bottom pot, simmer cider vinegar with some water. Add a bit of smoked meat (Chef Richards prefers turkey) and continue to simmer. Add crushed red pepper flakes to taste, then add seasonal greens (collards are good for fall). Depending on the bitterness of the greens, finish them with a bit of sorghum. Cook until almost tender, then turn off as they will continue cooking.

Chef Richards prefers to prepare his greens a day ahead, but only refrigerates if serving them more than 24 hours later, since the vinegar is a preservative. If refrigerated, heat in a heavy bottom pot.

Final thought: “If you’re putting more than six ingredients in your greens, you’re doing way too much.” – Chef Todd Richards

Photo credits, from top: Chef Todd Richards courtesy of Green Olive Media; The Shed Tuna Crudo by Chef Todd Richards; Chef Todd Richards speaking at the Atlanta Folklife Festival by Beth McKibben; The Shed’s Braised Collard Greens, Housemade Ding Dong and Hamachi with Onion Rings by Chef Todd Richards.

Beth McKibben is a freelance writer based in Atlanta. She enjoys telling a good story and day tripping with her husband and two kids. To find out more about Beth, see her full bio in our “Contributors” section.

Related Content & other posts by Beth McKibben:

Southern Food With a Story at Taste of Atlanta

Get Your Greens

Fried Green Tomatoes at the Atlanta Folklife Fest

Atlanta Food & Wine Festival Recap

Apple a Day

Pingback:The Real Roots of Southern Cuisine | The Lazy Susan / December 3, 2012

Tamika D. / December 13, 2012

What a fab read, Beth. That Atlanta History Center is THE GREATEST & Chef Richards food looks divine!

Beth / December 29, 2012

Tamika,

We need to go there for drinks and dinner! It’s wonderful and so are Todd, Cindy and Chef Richards! Love the crew at The Shed.

Gwendolyn / October 14, 2013

The comments regarding the African contribution to southern cuisine are greatly lacking in substance, truth, and in a basic understanding that the enslaved Africans found themselves in a situation in which they were deprived of sufficient food, sufficient time to prepare it and sufficient quipment with which to prepare it period. The Chef’s answers were basically unformed ones, based on wrong assumptions and incomplete information. As one who has lived in West Africa for more than eight years, and who has observed Africans growing, preparing foods and cooking certain dishes; let me assure you that the sautee, braise, simmer, steam, roast and bake are widely known and pacticed cooking techniques which are there; however, it is very difficult to do exciting things to foods when you are limited to only one or two food items, a pot, some water and very little time!

I’m not taking anything away rom the Indians or the Scandinavians, but it was the Africans who brought deep fat frying fried chicken, as well as one pot stews to this country. Fritters (batter-dipped and fried vegetables) are an African delicacy. Deep-fat frying has been attributed to Africa by mny other sources. The frying of foods is found all over West Africa, as all throughout the continent. This is because African cooks have a number of different oils that in abundance at their disposal such as: Palm oil, Coconut oil, Sesame and Olive oil, all of which are indigenous to Africa; however none of these oils are indigeous to North America. in use now in this country.

Africans have many ways to preserve foods: drying, smoking, salting, packing in oil. fermention, or packing with herbs and spices.

As for the comment that Africans never ate any beef until they came here, that is a complete and total untruth. Herds of cattle (Beef), goats, sheep, hogs, chickens, ducks and other farm animals are raised for their meat. Beef though expensive is particularly popular. In fact, cattle were introduced to Europe from Africa; when the British and the Dutch went to South Africa, they found Africans herding, butchering, and eating beef! The same is true for Europeans who went to West Africa they found pastoral people wih herds of cattle and other pastoral animals.

If you want to know more about what African slaves knew about food, you should travel to Africa where you would learn a lot.

Remember, in this country the slaves were given very few food choices by their masters — mostly those unwanted portion of foods, so the Chef made statements that were based on incorrect assumptions; the least he could have done, would have been to find out what food preparation/preervations methods existed in Africa, that may or may not have been practiced in common with Indians or Euopeans. He cannot correctly state for a fact as to what African slaves knew and contributed to southern cooking, by citing what they did with their limited ingredients when they cooked for themselves, or by wrongly assuming and attributing African cooking methods to other ethnic groups. When slaves had access to their preferred ingredients, appropriate equipment, and sufficient oil, seasonings, and more than one pot or skillet, they contributed richly to southern cuisine! Think about it, the mere fact that southern kitchens that boasted of hving the best in dining, were run by Black cooks, and not, say, native American or Scandinavian cooks strongly suggests that African cooks were perceived to be the best to be had in the South, and a white mistress who herself didn’t know how to cook, could not possibly teach this experise!

Pingback:Do you speak 'southern'? - Page 8 - City-Data Forum / January 27, 2014

Alan E. Young / August 18, 2016

Bless you my Sister,

Traveling coupled with reading, and research is a beautiful thing. Plantation owners did not bestow slaves with choice cuts of meats, (or any other products), learning to make do was a necessity. Black America in our stride to a taste of freedom, overlooked the greatest asset we had – Grandparents. Whether we call it “Soul Food”, or assign any other name, the bottom line remains the same; slaves used their

ingenuity, products they planted, and the undesirable morsels discarded by the plantation owners to create some heavenly dishes that will

tickle the tastebuds of the world forever.

Mary Ludie / March 2, 2014

Thank you for your post Gwendolyn. I found this site this morning while looking for a recipe on line. One search led to another and in every instance European influence was given top billing for every recipe and at best only a scant mention of african or native influence. What else is new? I searched for “why are Africans given so little credit for American cuisine?” and this article came up. I appreciate the article and Chef Richard’s contribution. It provided a platform forGwendolyn to expand the dialogue and educate further. It’s pathetic that the indigenous and African experiences in this country are minimized or non existent from everything. Many of our families continue to share the brilliance, ingenuity and creativity of an African tradition that was the force that helped our people survive, while this nations’swealth and culture evolved from slave labor and stolen land.

The legacy of the oppression and exclusion continues on a daily basis. A recipe search is only one of many constant reminders of a country that devalues non-European contributions.

Pingback:Southernisms: I Could Eat | progressiveredneckpreacher / August 30, 2014

Dee / September 28, 2014

Thanks Gwendolyn!

Pingback:The Heart of the Plantation and Root of Southern Cuisine | Belle Grove Plantation Bed and Breakfast / August 10, 2015

LD / November 23, 2015

YYEESSS @ GWENDOLYN! THANK YOU! I get tired of people acting as if enslaved Africans didn’t know anything and love attributing out Food/Southern Food to OTHER groups of people when in fact these same methods, types of foods etc were ALL READY present in Africa and they brought these skills, methods and foods with them! We are the backbone of the WORLD.

A few books to read on this are:

The SAGE Encyclopedia of African Cultural Heritage in North America (TWO VOLUMES)

What the Slaves Ate: Recollections of African American Foods

In the Shadow of Slavery: Africa’s Botanical Legacy

Pingback:Episode 36: Southern Food, Aunt Jemima, & Innovation - The Hidden History of Business Podcast / February 24, 2016

Pingback:Who is paying $66 for some collard greens? – NewsLocal / November 24, 2016

Pingback:Ain’t stereotypes lovely :) – Food For Thought / September 13, 2017

Pingback:Making Connections: A Step by Step Guide to Curating Content for a Killer Blog – The Fat Plant Society Blog Space / December 19, 2017

Pingback:Celebrating MLK with Soul – When I See You Again / January 15, 2018

Pingback:Thanking God for Black Southern Baptists — SBC Voices / November 2, 2018

david7134 / September 10, 2019

This article was on the brink of fiction with all the oh poor slave discourse, then it came apart completely when they said that water melon rinds were used as soles for shoes. It is logic, slaves were an expensive commodity. Often they were owned by the Northern banks and not the owners of the plantation, ie. Thomas Jefferson had little control of the destiny of his slaves due to Yankee control. Slaves were well cared for given the time. They had clothes for the season, shoes and fed well. They had a roof over their heads and were protected from the elements. They even had a doctor on most large plantations. I invite you to visit Melrose plantation in Louisiana, owned by blacks as were many plantations in Louisiana.

Slavery is considered an evil now, it was not through most of history and was the consequence of losing a war. In the early 1800’s the issue of slavery was in the fore front of American thought for a number of reasons, mostly political. In the South it was troubling for many whites as they were beginning to see the morality of the issue. The North had no problem hating blacks for the color of their skin, hence the Black Laws. This was not as much in the South until the Federal government made ex-slaves the overseers of the defeated people (who could not vote).

Blacks contributed to our culture, but to claim that our food was a major production is silly.

Sharon Piper / December 26, 2022

Gwendolyn, thank you for letting someone of my limited education be exposed to the information in your article. I ended up on web site almost accidentally.