Summary

- The Hindenburg disaster occurred 87 years ago today, impacting future airship travel.

- The crash was attributed to static electricity igniting leaking hydrogen gas.

- The catastrophe led to reduced public confidence and a decline in airship investment.

"Oh, the humanity!" Thus goes one of history's most famously quoted radio broadcasts of all time, uttered by radio journalist Herbert Morrison, as he was giving a real-time eyewitness narration of the Hindenburg disaster, a catastrophic fire that destroyed the Nazi German zeppelin LZ 129 ( (Luftschiff Zeppelin #129) Hindenburg. That sentence, as quoted, is shortened and oversimplified. Courtesy of Genius, here's a more complete excerpt that conveys a better sense of the mental and emotional trauma that Mr Morrison was experiencing:

"Oh, the humanity and all the passengers screaming around here. I told you, I can't even talk to people whose friends are on there. Ah! It's–it's–it's–it's ... o–ohhh! I–I can't talk, ladies and gentlemen. Honest, it's just laying there, a mass of smoking wreckage. Ah! And everybody can hardly breathe and talk, and the screaming. Lady, I–I'm sorry. Honest: I–I can hardly breathe."

That long preamble aside, the Hindenburg disaster occurred 87 years ago today, on May 6, 1937, at Naval Air Station (NAS) Lakehurst, New Jersey. What caused it, and how did it impact the future of airship travel?

Historical backdrop

When the Hindenburg made its final, ill-fated flight to the United States, Adolf Hitler and his Nazi regime had already been running Germany for three years. However, the onset of the Second World War was still three years away, and America's entry into WWII was still five years away. Ergo, in 1936, the U.S. was still very much engaged in diplomatic and trade relations with Nazi Germany. (Case in point: three months later, the iconic African-American athlete Jesse Owens won his four gold medals at the 1936 Berlin Summer Olympics, thus tweaking the nose of Der Führer and the notion of Aryan racial superiority.)

Thus, German zeppelins like the Hindenburg made routine flights "across the pond." Constructed between 1931 and 1936 and making her maiden flight on March 4, 1936, the Hindenburg made 17 successful round trips across the Atlantic—ten to the U.S. and seven to Brazil—in that first year of operations. She completed one Brazil round trip the following year, but her only US flight that year would be on that fateful May 6 day.

(A complete listing of the Hindenburg's itineraries can be found on Airships.Net)

Traveling aboard these airships was quite luxurious, almost the aerial equivalent of an ocean liner like the Queen Mary. As my Simple Flying colleague Nicole Kylie wrote during last year's anniversary of the fire:

"Given that it’s only recently that flying became more accessible to the masses, imagine just how opulent it was to fly in the 1930s when air travel was an exclusive, almost unattainable luxury. Airships, especially mammoths like the Hindenburg, were the epitome of status – and were undoubtedly regarded as the future of air travel."

This photo from the Hindenburg's dining room helps convey the sense of onboard opulence:

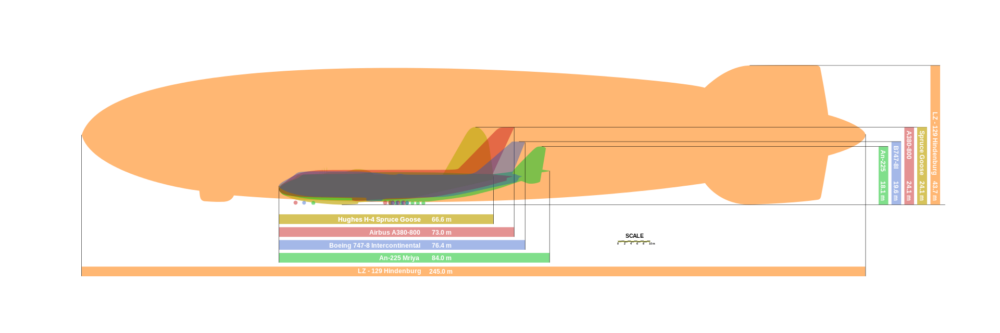

It was in that flying lap of luxury that the Hindenburg – at 804 feet (245 meters) length, more than triple the length the Airbus A380 – embarked from Friedrichshafen (the city where she was constructed, and which today hosts both a Zeppelin Museum and the Dornier Museum) on May 3, 1937, carrying 36 passengers and 63 crewmen (including 21 trainees) under the leadership of Captain Max Pruss, en route to their date with destiny.

How The Hindenburg Disaster Spelled The End For Interwar Airship Travel

The crash, deemed one of the worst air disasters, was a significant blow to the aviation industry.Disaster strikes

It was a 90-hour flight, which may be unfathomable for modern-day airliner passengers who find even an 8-hour flight uncomfortable enough (especially if crammed into Economy Class). Still, such was the nature of the proverbial beast back then, and at the least, the aforementioned luxury made the long flight more bearable.

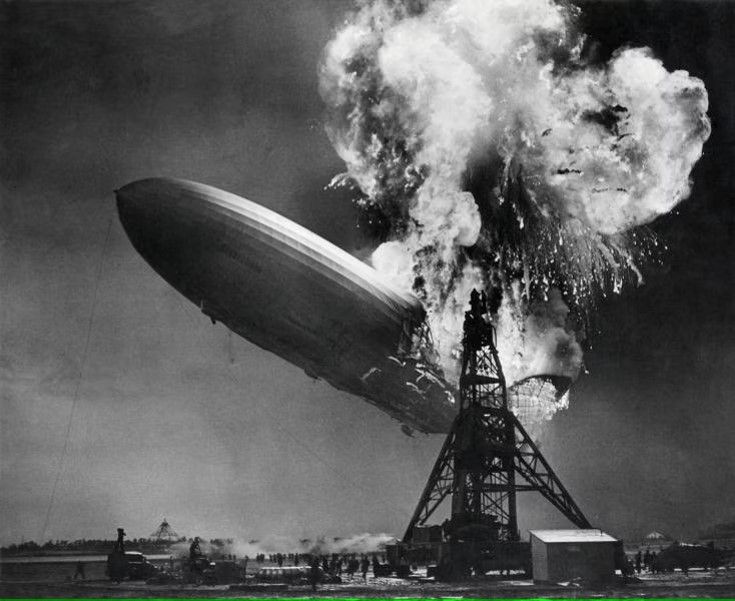

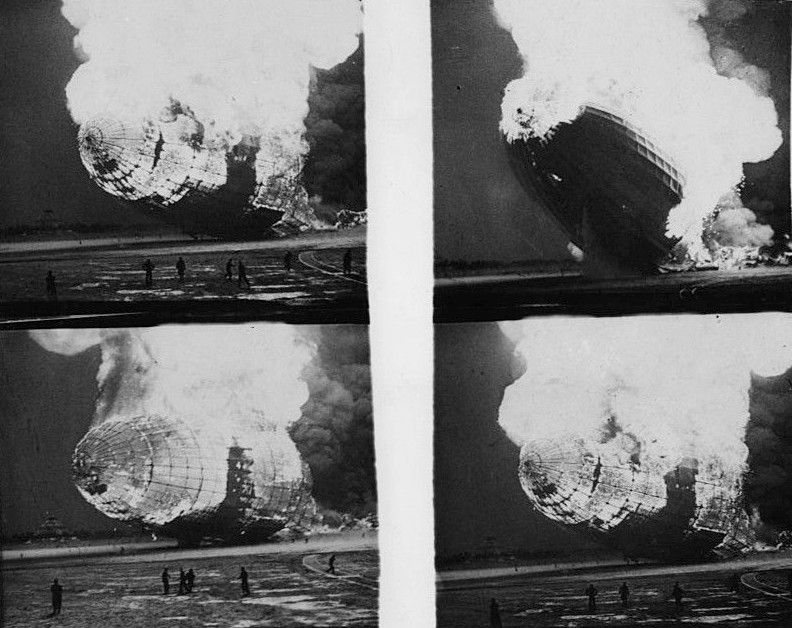

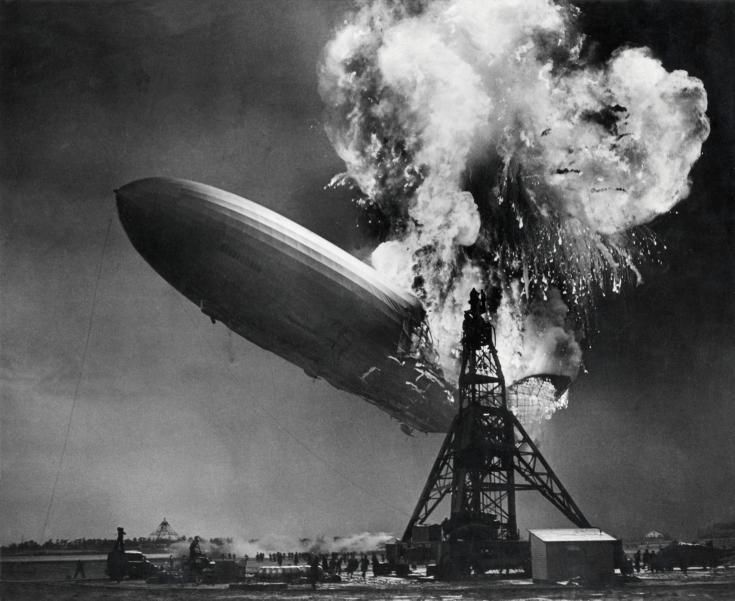

Fast-forward three days, and the behemoth blimp initially passed over Boston that morning. At 18:22 local time, Captain Pruss steered her toward her ultimate destination; the final approach was initiated at 19:00. At 19:25, the craft suddenly burst into flames, which quickly engulfed the zeppelin and sent it crashing to the ground.

36 human beings lost their lives; 13 passengers (a 36% fatality rate), 22 of the aircrew (coincidentally, another 36% fatality rate), and one of the ground crew. 23 passengers and 39 crewmen survived.

For the story of the world's first flight attendant and his lucky Hindenburg survival story, click here.

What went wrong? And what was the aftermath?

Conspiracy theorists, being conspiracy theorists, postulated the idea of sabotage. This was indeed the notion floated by author Michael M. Mooney in his 1972 book "The Hindenburg," which was adapted into a 1975 Universal Studios motion picture starring George C. Scott:

However, though still not 100% confirmed after all these years, the most commonly accepted explanation is that the star-crossed dirigible became a hotbed of static electricity after passing through a thunderstorm, thus igniting leakage of the blimp's highly flammable hydrogen content from a leaked gas line.

Whatever the true cause, the Hindenburg tragedy wasn't just a disaster in terms of human lives lost; it was also a catastrophe for the airship industry. As Nicole Kylie points out, airship accidents were nothing new. Still, the sheer volume of publicity surrounding the Hindenburg crash (such as the famous radio broadcast and newsreel footage included at the beginning of this article) severely undermined the general public's confidence in the safety of airship travel, which in turn led to a severe decline in passenger numbers and snowballed from there into a decrease in investment in airship technology development.

The severe PR damage, especially when combined with the ever-increasing tensions between Nazi Germany and the United States in the lead-up to World War II, dealt a death blow to interwar airship travel.

Not Just The Hindenburg: Five Other Infamous Airship Disasters From Years Gone By

Many of the world's great airships crashed at great loss of life - including those in US military service.So then, does that mean that airship technology is completely dead? Obviously not, as any American football fan who has watched TV footage of our beloved game from the Goodyear blimp can attest. However, between sports coverage and, for example, catering to tourists looking for more adventurous ways of exploring Der Deutschland, airship travel is a rare bird for a niche market.

Nonetheless, as my Simple Flying colleague Linnea Ahlgren points out in an April 2021 article, efforts are underway to breathe new life into the commercial airship industry, partially motivated by airships' fewer emissions. Linnea quotes Rebecca Zeitlin, media and communications manager for British firm Hybrid Air Vehicles (HAV):

“Commercial passenger transport isn’t dead either. We’re definitely talking to people who would like to use the craft to move people in a more traditional way because there is quite a strong flight-shaming movement who think ‘I’d rather take longer, pay more and generate fewer emissions.”

Will airships one day make a comeback? Stay tuned, ladies & gentlemen, and share your thoughts in the comments.